Episode #143 Hagitude: Paving the way to an empowered elderhood with Sharon Blackie

“As elders, our job is to die, as eventually we come to live — always in service to life.” How do we do this? How can we pass into our elder years with grace and rage and depth and honouring of who we are, and emerge wiser, and more attuned to our soul’s calling. With Dr Sharon Blackie, author of Hagitude.

Dr. Sharon Blackie is an award-winning writer, psychologist and mythologist. Her highly acclaimed books, courses, lectures and workshops are focused on the development of the mythic imagination, and on the relevance of myth, fairy tales and folk traditions to the personal, social and environmental problems we face today.

As well as writing five books of fiction and nonfiction, including the bestselling If Women Rose Rooted, her writing has appeared in several international media outlets, among them the Guardian, the Irish Times, and the Scotsman. Her books have been translated into several languages, and she has been interviewed by the BBC, US public radio and other broadcasters on her areas of expertise.

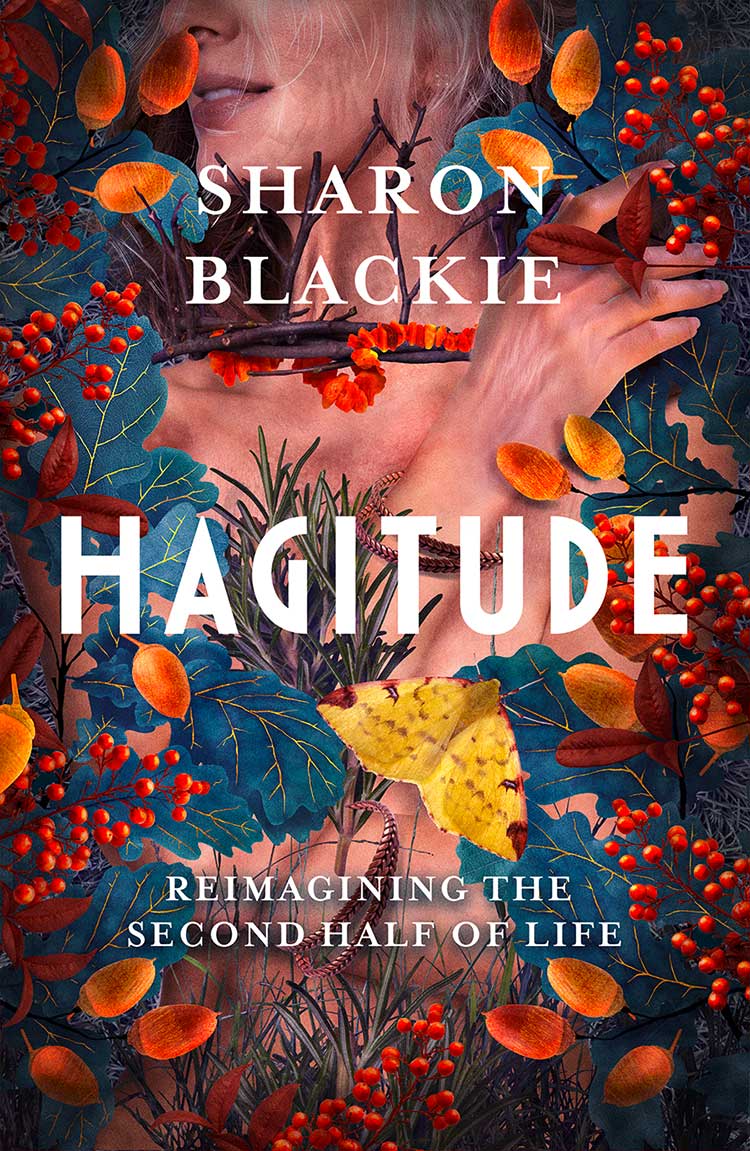

In today’s episode, we explore the writing of Sharon’s latest book, Hagitude: Reimagining the Second Half of Life – what it is, how it came about, how the powerful old women of the European folk tales provide a model for what it is to live in the second half of life: we explore alchemy, the magic of the land, the Cailleach, death, dying…and Terry Pratchett’s Granny Weatherwax as the ultimate role model for older age!

Episode #143

LINKS

Hagitude website

Sharon Blackie author website

Sharon’s podcasts dedicated to Hagitude

Accidental Gods Episode 90 with Sharon

Sunday Times Review of Hagitude

In Conversation

Manda: Hey, people. Welcome to Accidental Gods. To the podcast where we believe that another world is still possible and that together we can make it happen. I’m Manda Scott, your host at this place on the web where art meets activism, politics meets philosophy and science meets spirituality; all in the service of conscious evolution and increasingly in the service of finding a way through to that flourishing future that our hearts know as possible and that we would be proud to leave to the generations that come after us. My guest in this episode has been with us before. Dr. Sharon Blackie spoke to us first way back in episode 90, and I will put a link in the show notes. But she’s back today because she has another book out and it’s recently been reviewed in The Times. And I can do no better than to read to you something that Christina Patterson wrote in that review. Blackie is a writer and psychologist, fascinated by the interface between psychology, mythology and ecology. She has written two novels and two non-fiction books exploring it, including the eco feminist bestseller If Women Rose Rooted. She runs courses and workshops on the development of the mythic imagination. She knows her archetypes, knows her Jung, knows her fairy tales and knows her neuroscience, and is sick of being patronised by men who don’t. Not just men, I have to say.

Manda: I think Sharon is so erudite and goes into such depth in her writing, but it’s always an honour and an edgy excitement to speak with her. Because we always find that edge where understanding meets a deep felt sense, and then we can explore along it. And we’re here today because she has a new book recently published, Hagitude; Reimagining the Second Half of Life. And it is, I would say, one of the best things she’s written, if not the best. It’s a very lucid, very beautiful, very moving, very magical exploration of moving into elder hood. And it is, of course, explicitly aimed at women. It’s taking the archetypes and the figures of the old wise woman in all of her forms, from European folktales and to some extent mythology and weaving through it Jungian archetypes and alchemy and Sharon’s own story of her very close brush with death. And all of these are woven into today’s podcast as we explore them and go down the rabbit holes of fascination, with someone whose mind expands and extends far, far beyond the usual run of the mill. So people of the podcast, please do welcome Dr. Sharon Blackie.

Manda: So, Sharon, from your home in the middle of Wales, welcome to the Accidental Gods podcast. Thank you for joining us on this beautiful sunny morning. How is it with you in Wales?

Sharon: It’s wet. Oddly enough.

Manda: And miraculously, I don’t know about you, but we’ve been praying for rain. Have you?

Sharon: I am all ready for autumn. I’m done with summer after the last couple of heatwaves. So yes, I have been for sure praying for rain, cold, mizzle, drizzle, all of that really wonderful stuff that gets my creative juices flowing.

Manda: Yes. Because I remember one of our previous conversations, you said that you loved midsummer because it meant that the days were becoming shorter and the nights were becoming longer and we were heading down into winter. And I know so few people who really enjoy mid-winter, and I wonder you don’t have to tell us when your birthday is, but were you a winter birthday person?

Sharon: No, I was born actually at the end of June, but at least I was on the downward slope. And it is curious that that doesn’t seem to bear any relationship to my preferences, any more than the fact that I was born in the north east of England seems to make any difference to my preferences always for the West. So it’s just one of those strange things.

Manda: Yes. Because through your life you’ve been a West Coast person. And I wonder, yes, again, because that’s where the Gaeltacht is, in Ireland and in Scotland. And even if we assume that Wales is the Gaeltacht of of England, then Wales as well is that. Brythonic languages anyway. So let’s not get hooked into language just yet, although I was fascinated to discover that your husband is now completely fluent in pretty much all of the Gaelic languages. I’m very impressed. You have just finished and published Hagitude. Why am I holding it up for the screen? There will be a picture on the website, people, you can’t see my screen. It’s a beautiful book in all respects. I love the cover, I love the concept. It’s called Re-imagining the Second Half of Life for Women explicitly, I would say, although I’m sure that men reading it would find a lot of depth and a lot to engage with. So I want to explore the intricacies of this book. Starting with what drew you to write it? Why did you feel this was a gap in the market or a gap in our knowledge, perhaps? And why did you feel that it was a gap that you could fill?

Sharon: I think that at the time that I began to write it and I began to write it probably in about 2019, if I remember rightly, there were not very many conversations around menopause and elder hood of the kind that are beginning to take place now. But even now, the conversation seemed to be more on well-being and health and staying young-looking and beautiful during menopause and elder hood, and not on inspirations for actually going through it, doing it fully, and maybe actually finding yourself transformed in a positive way by the experience. So that was really what I wanted to write about. And for me it was a consequence, I suppose, of being in my late fifties and I’d always seen sixty as a kind of barrier year. You know, not like something radical would happen and there’d be a sudden transformation, but 60, it’s like, Oh, that’s a serious year. Now you’re moving slowly into Elder Hood and what did that mean to me and what was I going to become? And there weren’t any really interesting, for me anyway, inspirations out there. So as always, I went looking for them in the old stories and myths and I found more than I’d bargained for and just thought, well, there you go: There’s there’s my next book.

Manda: Yes. And it comes as it feels like, if we were to look at it in retrospect, a very obvious continuation after If Women Rose Rooted and Foxfire and the others. You’ve been exploring myth in your written work and your online trainings for decades now, and yet, as you say, there wasn’t a good, strong sense of somebody pulling together all of the archetypes across all of the planets, of it being okay to grow old as a woman. And particularly in our fairly toxic, fairly damaged, it has to be said Western culture, where growing old feels – and you say this somewhere in the book – as if it’s it’s a penance and a punishment. And that’s what happens when you do the bad stuff and the good people get to stay young forever.

Manda: So to explain to us a little bit about where you were when you started writing? Because you’ve done a lot of moving recently. You were in Ireland having moved from Scotland, is that right?

Sharon: Yes, we had been at that stage at the point that I had the idea for the book, we’d been in Ireland probably five, getting on for six years. And yes, it was a kind of continuation from If Women Rose Rooted; using the same idea that there are characters in those stories that can… Not provide blueprints for living, but inspiration for how to be in the world and also how to be in a very, very challenged world. And as you know, stories have always been the places that I look to for inspiration, partly because of my work as a psychologist, where I really focussed on narrative psychology and on helping people to reimagine themselves and their place in the world. And stories always capture the imagination. Not everything does, but stories almost always do. I’ve really never seen them fail. So to me, to go to those stories, to look for examples, inspirations, something beautiful and magical that can really capture the imagination, was what I wanted to do. And, you know, Ireland is a place where I have always found it easy to have my imagination stimulated.

Manda: Yes. When you first went there, you say in the book that one of the old farmers came to visit you and said something along the lines of, so do you follow the faith of the faery?

Sharon: The faery faith.

Manda: And presumably he hadn’t just read your entire over and knew who you were. This was just a question that you asked of people who just arrived?

Sharon: He did know that I worked with myth a little bit. But that was just.. I mean, he was a farmer, you know, a bit of a musician, but not anybody who had a particularly sophisticated education. But in that part of Western Donegal, as it was at the time, it’s just it was yes, it was the obvious question to ask. Because it ran what they call the Faery Faith in parallel with Catholicism, you know, so they’d go to church in the morning and they’d go home at night and put a saucer of milk out for the faeries in case they were hungry when they passed by. And it just it’s been like that for a very long time. And it’s disappeared in some parts of Ireland, of course, but not all of them, as I found.

Manda: Yes, clearly. And there you mention, along with the mythology of people who are clearly mythological in the book, some stories of women whose histories have come down to us and some of them who were healers, who I think probably like homeopaths in the modern world, they’d be everybody’s last resort. And their first question would be, what have you done to upset the faery folk in the area? And I’m really let’s just explore this. We’ll come back to the book in a bit, but did you have a sense when you were in Ireland and perhaps in the West of Scotland and perhaps now in Wales, of connecting with that? First of all, the faery faith as a faith and second with whatever it is in the land that takes that label. Does that make sense as a question?

Sharon: Yes. I mean, really, what they call the faery faith now would be a kind of, if I could put it that way, and I don’t mean it in a negative way, the kind of degraded down through the centuries perspective on the old mythology of the gods. You know, the Tuath Dé Danann and the Bridget’s, the Morgans and so on. And at some point, to cut a very long story short, at some point in history those gods began to be called the faeries. So it’s a kind of continuation, but it has been a little bit downgraded. Now, these are not twinkly little fairy creatures. These are tall, you know, sometimes dangerous, very serious beings. And, yes, I think the Scottish and the Irish parts of my heritage, which are quite a lot of it, certainly the majority of it, always lead me to those particular wild and bleak and very dramatic locations where I can find that connection with the land and with the other world that Irish and Gaelic mythology tells us is completely embedded in the land. I can find it there. I find it much harder in Wales, but that’s a different story. And that’s where my impetus, I think to go and research old women in European mythology came from. Because of course in the Gaelic culture we have this wonderful character, the Cailleach, which literally means the old woman. And she is kind of the land personified. She is portrayed as the creator and shaper of the land. Not the creator and shaper of the world, because we don’t unfortunately have a creation myth left to us, but the creator and shaper of the land, and particularly in the rocky and wild places. So in a sense, for me she personifies everything that I love about that kind of geology and those particular places the language, the culture, the faery faith, the mythology that we find in those parts of the world.

Manda: And when you were in Scotland, you were in the very west of the Western Isles of Scotland, you found a particular rock that you called the Cailleach. Can you tell us a little bit about the finding of that and why it seemed special and then about what happened when you left? Just because in terms of engaging with the land, it struck me that that was a really deep and profound and personal and moved into that area of magic interaction that our Western Left Hemisphere brains don’t really engage with very well.

Sharon: Well, when I moved to the Isle of Lewis in the Outer Hebrides, there was a great residue of stories about the Cailleach there. So there were lots of place names that were named after her. There were lots of mountains that were named after her. And there was a tradition, particularly in that part of the world, of being able to see the shape of reclining females in the shape of mountains. So there’s a very famous one, the Sleeping Beauty Mountain, which is visible from Callanish, the stones on the Isle of Lewis, and it looks like a woman lying down in the landscape. She’s called the Sleeping Beauty in English, but in Gaelic her name is Cailleach na Mointeach, which basically means the old woman of the Moors. So interesting that the old language retains that respect for the old woman in the place name. So there were lots of examples of the Cailleach and I began to be very interested, inevitably, in her folklore and in those places. And we had a reclining figure in the mountain directly opposite our house. So I was kind of attuned to the fact that there were these characters in the mountains, and I’m a bit of a pareidoliac I do tend to see faces and shapes and figures in things. And one day I happened to cross a place that I subsequently called the Rocky Place, which was down below the headland so that you couldn’t actually see it from the headland.

Sharon: A kind of second level, almost as if you were taking an elevator down before you got to the sea. And it was a rocky carpet, remarkable place. And I found a stone there, a rock at the edge of a cliff face, which seemed to me to have the silhouette of an old woman standing, looking out to sea sideways. And I thought, great, you know, I found the Cailleach. There she is. And that whole place seemed to me, because it was very much associated with rock and very windswept and all of the places that the Cailleach in the folklore and the mythology inhabits. The whole place seemed to me like a Cailleach place. And there was a funny little alcove in part of the cliff face, which was for all the world, like a kind of a sofa bed. It looked like a giant rock sofa, like something out of the Flintstones or whatever. And it was just human length. And a couple of nights towards the end of August, when I was getting a little bit mad because of the lack of dark that there is in a hebridean summer, I would sleep out there so that I could actually see that there were stars still left in the world, you know. And I called it, just laughingly,the Cailleach’s bed, because I was sleeping there and I kind of fancied myself as a bit of a Cailleach even then. To cut a very long story short, after we left Lewis, my husband went back.

Sharon: It took us a long time to sell our house, and my husband went back to collect some things that we had left there when we finally did, about 18 months later. And I said to him, oh go down to the rocky place for me and, you know, and say hello to the Cailleach and all of the other beings that I’d found there in the rock. So he went down there and found that the Cailleach’s bed had completely disappeared. So this was an enormous lump of very, very thick of lewisian Gneiss. You know, this is not light, sandstone or chalk, this is Lewisian Gneiss. It is heavy. It was wedged into an alcove. And the bit that you might think of as the mattress had completely gone and all that was left was an empty alcove. Now, you know, the sea can do remarkable things. I’m very much aware of that. I’m a scientist by training, but that just seemed a little bit too much of a coincidence to me. And and I felt very much that I’d grown to love that land. I’d courted the land and the beings, you know, other worldly or physical that inhabited it. And then I left it and I kind of abandoned it. And it almost felt as if that was an expression of the land grieving, maybe in the way that I kind of grieved for leaving it myself.

Manda: Wow. And did you feel… You moved from Scotland to Ireland, which culturally and and geographically and geologically are quite linked. I remember going to Fingal’s cave and seeing the extraordinary stone formations that go out and basically link Scotland to Ireland in geological ways. Did you when you get to got to Ireland feel as if there was a Cailleach there waiting for you? Had she perhaps come from Scotland to Ireland or had she just stayed in that place, and you were without an old woman when you got to Ireland?

Sharon: So the Cailleach really would have been as ubiquitous, if not more ubiquitous in Irish myth as in Scottish myth. And of course the texts are much older in Ireland. So she was very, very much there. And we landed in Donegal, where for centuries there had been a strong trading relationship with particularly the southwest of Scotland and the islands, because of the sea route, which was very, very easy and actually very short. But I did actually curiously land in a part of Donegal, in a part of Ireland and a part of Donegal where there was no Cailleach to be seen. There were no place names named after her. There were no stories that I could find. And I did feel completely bereft. And it took me a while to find my old woman archetype in the landscape. And I did, eventually. So one day I was walking along the river and we lived near a heronry and there was a heron in the middle of the river and we startled her. It was early morning, I was there with the dogs and she took off and she flew into the sky. And I thought to myself, Good heavens, she’s shrieking for all the world like an old hag. And then I thought, there you go. And by the time I came back from that walk, an image had appeared in my mind of a character that I subsequently called Old Crane woman who was half heron. Herons and cranes are interchangeable in Irish myth and in the language too. Who was half heron and half woman. And by the time I got back from the walk, she had also developed a distinctive voice. And I wrote about her. Basically, I wrote a blog about her for about three years running around the winter solstice. So that to me is how you can find and connect with old woman energies in the land without having to necessarily have pre-existing stories.

Manda: Beautiful. So we can, in a way, re enliven myths and and have them real and and vibrant for us in the modern age, when it feels as if myths; it certainly feels to me; as if myths can be quite pushed away by the immediacy of of television and of novels. I would like to go back a little bit. I want to come back and explore the Cailleach and other archetypes. But you said earlier on, everybody responds to story. And we’re surrounded at the moment in our fracturing and increasingly divided world by ‘us and them’ stories. And I wonder what for you are the components of stories that are generative for everybody? Because there must be, in the old myths, I hope, I believe I may be wrong. You can tell me if I’m wrong. Ways of finding story that could unite our various disparate factions. So can we unpick story a little bit? And what is it about stories that you were using in your psychotherapy practice and that then become applicable in the wider world?

Sharon: I would say that it is easier to work in that context, particularly in psychotherapy, with fairy tales and folktales rather than myths. Myths often tend to be very much grander. You know, their aim is to explain the world and how it is constructed and our place as humans in it. So some of them are accessible, some of them are not so accessible. They can be a little bit kind of dour, you know, in a way, whereas fairy tales, coming from folktales by definition, coming from the folk, coming from the people who are living in the world, who are using these stories to inspire and explain their everyday lives. They tend to be a little bit easier to work with, a little bit more accessible. Now, the reason that they are so powerful in psychotherapeutic terms is very simply because of the imagery. So you have these very simple stories where the characters are not particularly drawn in any great detail, but they are archetypal characters. They are the hero, the fool, the trickster, the mother, the queen, the wise old man. You know, all of these archetypes appear very, very clearly. Wearing different clothing from story to story, but nevertheless you recognise they are archetypes, we recognise archetypes. And then you have beautiful images.

Sharon: So for example, I used to use the story of the Red Shoes a lot when it came to addiction. Because that whole idea of, you know, you put on a pair of shoes and then the shoes end up dancing you. You don’t have any control anymore. Perfect metaphor for the process of addiction and the fact that you can see something that clearly in your mind, that you can relate it to a story, to a character, somehow makes it all the more easy to digest. The handless maiden is another one. Was she abused by her father? By the devil? There are some versions of the stories where that happens. You don’t have to talk about it. She had her hands cut off. You don’t have to name the abuse. She had her hands cut off. And then you can talk about having your hands cut off. Do you see? So you don’t actually have to use words for something that are wordless for you. So mostly the images and the nature of the archetypal beings that inhabit them.

Manda: Beautiful. Okay, so let’s have a look at those archetypal beings. You, at one point in the book discuss, I think, four archetypes that were were both Jungian and intrinsic to folktales. Can you talk us.. And these are archetypes of womanhood…talk us through those four and let’s see where we can take that.

Sharon: I think what you’re talking about is the concept of the archetypal medial woman. And this was a name that was given by Toni Wolffe, who was both Carl Jung’s lover and his student, to what she conceived of as being the four key elements of womanhood. Now, clearly, this is a very personal perspective on womanhood. They may not be the only four, but they are four that are kind of interesting. So there was The Mother inevitably, everybody knows the mother figure. There was The Amazon who was, you know, the strong kind of woman who could take on roles and jobs, let’s say, that were classically associated with men. There was The Hetaira, who is a kind of muse figure. It’s a Greek word for kind of a prostitute, but a high level prostitute who is more of an inspiration rather than just a kind of physical vessel. So a kind of a muse figure. And then The Medial Woman, the fourth one of those is the only archetype that is not defined in relationship to somebody else. So the mother is, you know, to her children…you get the gist. The Medial Woman is very much kind of alone with herself or she’s sufficient to herself. And she appears at a time in a woman’s life where you’re beginning to turn inwards, kind of for the source of your own wisdom. So it’s very much a middle life archetype where you’re looking for the mystery, you’re looking for what it’s all about. You’re looking for the nature of your own calling. You’re beginning to question, as people do at midlife, what is this all about? And what on earth am I going to do with the time that I have left? What are all of these years that are stretching ahead of me actually for?

Manda: Beautiful. And what I really liked about the Media Woman, because you’re right, that is where I wanted to get to. Was that almost uniquely it seemed to me and again, I suspect my understanding and knowledge of folktales is deficient here. But I was struck over and over again by the heteronormativity of it, but also the the way women in particular from the young girls onwards, were defined by seeking a husband or how they worked. There was an extraordinary folktale that I had never heard before of the stepdaughter. It’s always there’s a stepmother who doesn’t like her, and has the preferred child. And she’s spinning and she drops her spindle into the well. And rather than suffer the wrath of her stepmother, she throws herself into the well, because that’s obviously a wise thing to do and then has a series of visions, which, as far as I could tell, if you boil them down were: be a very good little girl, do exactly what you’re told. Subsume all of your own wants to the authority figure who tells you what to do and life will work out fine. And it left me with my head exploding into tiny fragments. And yet, that kind of… And she’d been told all of this… The person, a figure who in fact rescued her from the well was a wise old woman, a sort of a Baba Yaga kind of a figure. And that seemed to be the role of the wise old woman. Was to train younger women to be very hard working, polish the floors, do all of the spinning and all of the knitting and all of that good stuff. And then when you’ve done that, the nice guy will come along and rescue you and it’ll all be okay. And as someone who never particularly wanted the nice guy to come along and rescue me, am I seeing this through a particularly warped lens? Yes. You’re nodding. Okay. Tell us why I got that wrong.

Sharon: It’s not that you’ve got it wrong. On the one hand, we have to agree that folktales and fairy tales, their function is in good part to provide kind of teaching stories, if you like, for how the local world is and how one should behave and the kind of characters that one will meet. So back in the day, almost everybody had stepmothers because most women who had given birth to a bunch of children weren’t alive to tell the tale. So you see these situations that are a function of the time in which these stories arose and in which they became very widely disseminated. So that’s one thing to bear in mind. They’re kind of products of their time. And because we have stopped largely the oral tradition ourselves, these stories have become kind of static. They’ve become fossilised. They’re not growing anymore. That’s my passion, really, is to see how can we make them grow so that they are relevant to today’s world, not to a world that was, you know, 500 years old and was facing quite different challenges very, very often. But the second point is that they are intended often to be metaphorical.

Sharon: So, you know, we have all of these situations where young girls appear in the story and they are tested, let’s say, by the wise old woman who wants them to sort wheat from other types of grain. Now, that isn’t because anybody thought this was a useful thing to do. It’s because it was about some kind of psychological sorting. You know, you need to be able to sort in your life, you need to be able to discern. And so very often even, you know, the prince at the end of the story, in some of the old stories, was really kind of a metaphor for fulfilment rather than you must get married and, you know, behave yourself and be a good wife to a very dull, probably, husband. So I think it’s if you’re going to actually find these stories useful, I think it’s important to try to step out of the more literal meaning and the more historical meaning and just say, okay, what is this story really telling us about the human condition? Beyond the, you know, the specific daily detail, if that makes sense.

Manda: It does. I would love to go into that one in more depth, but I have a suspicion that we would be mining my own psychology, and that’s probably not useful for the podcast. It does seem to me that a lot of these stories involve young girls being given very menial, dull tasks that nobody else wants to do, and it is their job to buckle under and do them. And I can see that there may be a metaphorical sorting the wheat from the whatever else, the mouldy rye. But you’re also sweeping the house and doing the ironing and chopping the wood. And you’re basically being told your job is to get on with the work. Were there equivalent stories for young men that I just don’t know about, because folktales are not my thing? Do young boys also get told fairy stories where their job was to chop all the wood and clean the house and do all of the menial work.

Sharon: Yes, there are many, many stories, particularly in Ireland and Scotland, about farmers and farming boys. So, yes, there’s such a wide variety of different types of folktale and different types of fairy story, even within the same tradition that it’s incredibly hard to overgeneralise. There are all kinds of stories where young girls actually do very much more magical things and you know, the wells and the kissing the frogs and all of this kind of malarkey. So, you know, the ones I suppose that I focussed on in Hagitude, because I was really focusing on the old women who, as I say in the book, are very rarely the protagonists of the stories. But they are the ones pulling all of the strings. And so it is very, they tend to be, not exclusively but tend to be very much about teaching the younger people skills for life. Now, that may have been back in the 1700s if she were a young, poor girl of the people, sweeping. But nevertheless, I do believe that everybody understood that there was more to it than just being a good sweeper. That it was really about learning, teaching them, the old women teaching them the skills for life. And what was rewarded more often than not wasn’t necessarily that you swept very well, but that in facing a task that appeared to be impossible, you knew how to bring in the allies. You knew how to persuade the mice to help you sort, by giving them a little bit of your daily porridge, for example. So really these are stories about on the surface sweeping and sorting, but really about deeper, more profound skills for life. Like building a community of people or beings, animals who will actually help you, by being nice to them, by being kind to them, by giving them something in return.

Manda: Yes, because there does seem to be quite a lot of connecting with the more than human world. What we would now consider potentially shamanic work or even just basic earth magical work. And the fact that that’s survived two millennia of patriarchal Christianity is quite amazing, I guess, and it would have to be hidden quite, quite deep in the structures of these things. How far back… We’ll leave folktales in a bit, but I’m just curious. How far back can we do the kind of linguistic forensic archaeology, to assume these things go? Do we have anything that survives in Western Europe from our pre-Christian and preferably forager hunter past? Or would we have to look to folktales from more recently Indigenous peoples to find those?

Sharon: It’s incredibly difficult to trace things back in the oral tradition by definition, because it is the oral tradition where we are very fortunate in this part of the world, as in Ireland certainly,the stories began to be written down for the first time, you know, back in the in the seventh century. Now, they were written down by Christian monks, who were the only ones who were able to write at the time. But they were done very much in collaboration with the local bards and scribes. And so for some stories, particularly from the Irish tradition, we can trace how they might have started as a saga or a proper myth, you know, with potentially spiritual overtones and passed down through the centuries as something slightly different. Once the patriarchy, Christianity, just the passage of years, had transformed it. A little bit like the gods becoming transformed into faeries. So sometimes you can trace it, so we know how it can happen. But for most things, if they were in the oral tradition, we really don’t know very much about them at all. Certain motifs that happen all over Europe, like the the Cinderella motif, you know, happens in pretty much every country in one fashion or another. And by looking at where they arise and when they began to be written down and where they were first recorded, you can get some sense of it, but it’s incredibly difficult to do.

Manda: Okay. Fair enough. I was I was entertaining happy fantasies. I remember working with Carolyn Hillier for a little while and she had worked with some forensic linguists in Oxford. And I have no idea how they’d done it but they had re recreated they believed, the language that would have been around in southern England in pre-roman times as a forensic linguistic, archaeological project. And then she had written songs based on it and singing those songs as a group of women, just in a village hall in Devon, made my marrow melt. My bones felt different. It was really interesting just giving shape to words that felt as if somehow they resonated in my DNA. And I wondered if that work extended into folktales. But as you say, it would be incredibly hard and I don’t know quite how we’d do it. So let’s leave that, because I could carry on down that rabbit hole. But let’s not. Let’s come back to the book because there’s so much and it’s so rich.

Manda: And I’m interested in the fact that this is both an exploration of folktales and the ways that women have been depicted across time and space, and also of your own journey. Tell us a little bit about your transition from Ireland to Wales and what that did physically and psychologically, because that happened during the writing of the book.

Sharon: I think I was asking myself not only what kind of an elder I was going to become, but where my work would be while I was an elder. And again, if we if we can mention Caroline twice in one podcast, she has a wonderful line in one of her songs.

Manda: Let’s do it.

Sharon: I think it’s Forest Yarn. Where will you lay your bones, my dear, when all is said and done? And that line haunted me. Was it Ireland? Was it the UK? And I felt very much that I had not come to terms with the part of my ancestry that would be in what we call Hen Ogledd, the old North, which is part Britain and Part Scotland. My father’s ancestors are from effectively the borders all the way up to Edinburgh. Some of my mother’s ancestors that are not Irish are from the north of England. So I didn’t want anything to do with England. I wanted to do with Ireland and Scotland. I thought that was more romantic and I didn’t relate very easily to Englishness as a history, as a colonial power or any of that kind of thing. And it was associated with my mother, the north of England, where I was born, who I’d had a very, very difficult relationship with. So that was a place I was just not going to go. And the more that I started to think about hagitude, just in the back of my mind, not as any particular consequence, I just started to feel nagged by the fact that I had not come to terms with a whole part of my ancestry and place.

Sharon: And I just, to cut a very long story short, I just felt very drawn to returning to Britain. Would it be forever? I didn’t know, but I felt that I hadn’t come to terms with it. And I needed to. I needed to in some sense come – it’s not full circle because we spiral, don’t we? We go out and we go back in again. We don’t come back to exactly the same place – but in a sense it’s coming full circle. I felt that I needed to do that. So David, my husband for different reasons, was also up for that. So we came back. So it was very much about searching for traditions, stories that I was less familiar with in a place that I’m less comfortable with and a sense that in some way, this sounds awfully self-serving, but that my work was perhaps needed here for a while. Not necessarily where I’d been comfortable, in Scotland and Ireland for all those years.

Manda: And so you set about moving just as COVID hit.

Sharon: That was great, wasn’t it? Yeah, that was a really, really good choice. And it was kind of very funny that the whole thing that happened after we made that choice, was very much I felt as if that old Cailleach was saying to me, Hmm, you want to write a book about Elder Hood? I’ll give you Elder Hood! And you know, there’s the initiation from hell, because it was in every possible way. So I’m kind of grateful for that now but at the time it was pretty hairy. So yes, we ended up effectively making a run for it as all ports and borders appeared to be closing down around us. Almost ended up between houses with nowhere to go with us and four dogs and a cat and what have you. We ended up here in this house on the first day of lockdown, and then our movers decided that they weren’t entirely sure that they were allowed to come and bring up all of our things. So we ended up in this cold old house in a place that we didn’t really know. We didn’t know how it worked because we’d never met the previous owners. And we just.. We didn’t know what to do. You know, you couldn’t just pop out and buy things because all the shops were shut and you weren’t allowed. So that was very traumatic. And as a consequence, I suspect of that, I got a full on inflammatory, incredibly severe and disabling inflammatory arthritis. We didn’t know what it was for a long time. Now, of course, I do know. Which subsequently about just under a year later was clearly associated with the lymphoma that I was then diagnosed with. It was all part of some what I think of as an inflammation bomb that kind of hit me. And it was an aggressive form of lymphoma. It was really hard to get it and anything diagnosed, in the context of a health service which was not entirely operating at its best. And so yeah, it ended up being a very, very big modest initiation I suppose.

Manda: It feels, having listened to you several times speak about this, but also reading it again in the book, that this was an elderhood rite of passage. And I wonder, because we’re talking with folktales, we’re talking in our history and to a lesser extent in the present, actually a much lesser extent in the present. So few women survived motherhood. The elders were the ones who had either physiologically not been able to be mothers, or were the nuns who’d survived because they were not required to reproduce. Do we have in our history and our folktales much of a sense of an elder hood rite of passage? In the way that there are very obvious kind of teenage childhood to adulthood rites of passage. Or is this something that you had to reinvent for yourself?

Sharon: Well, no. The short answer is no we’re not familiar with any such rites of passage. Probably wouldn’t necessarily recommend mine as the way to go, although it was very, very effective. But that is actually that whole question of how do we prepare, how do we do a kind of Vision Quest for Elderhood is something that we’re going to be looking at in the course of the year long membership program that I’m running around Hagitude. Because it seems to me that some ways of marking that, and of course you can mark menopause if you have the kind of menopause which is kind of neat and tidy. You know, where your periods stop and then literally a year later, I think it is, menopause is officially said to have occurred. So you’ve got some kind of physical marker there, arguably for most women, not all. But we don’t really have the psychological markers. And Menopause, particularly as a rite of passage, interests me. But also, I think post menopause a little time after menopause, depending on when you have menopause. There’s another thing that happens. I went through menopause at 50. That wasn’t much of a rite of passage for me. I had symptoms of some kind, but it wasn’t much of a big change. My big change came when I was more approaching 60. And so I think that there are real needs and benefits to the idea that we think about how we mark those and how we treat them as initiations. In preparation for, you know, the final rite of passage. I mean, this is a journey that ends in death by design. And I suppose I had a little bit of a feel for that walking through the valley of the shadow of death, as I think of it, for a number of months while I was undergoing treatment. But we need something like that, it seems to me, where we can kind of rehearse what inevitably is going to come.

Manda: Yes, because you say in the book, towards the end, as Elders our job is to die as eventually we came to live, always in the service of life. And you are one of those women that I know most lives in the service of life. And a lot of people are still struggling to find that or even struggling to just cope with living and haven’t got onto the path of trying to find their service for life. If I think about my mother’s generation, my parents generation, and a lot of the people that I know of that age, it is my projection but I watch them walk into death with no sense of preparedness for it at all. Often in deep, deep denial. And it seemed to me from the outside, not having found their soul’s dance. And so how would you help people in our era of any age find their soul’s dance, find that sense of service to the earth and to the world, to whatever it is that we serve, in order that they can walk into death with a sense of clean stepping.

Sharon: Yeah. For me, this comes down to the idea of what tends to be in the kind of depth psychology world called Calling. And I write about that a little bit in the book. So the argument would be, from a Jungian perspective particularly, that the second half of life is about this process that Jung called individuation, which is very much about figuring out who you are and why you’re here and how you can best serve the world. So that in the first half of your life, you’ve done all of the building and the creating and the playing and the growing and, you know, in whatever fashion that has taken. But at midlife there is a shift, and the shift is a kind of turning inwards, not to navel gaze, but to question what the purpose of life is. And the notion of Calling goes right back to Plato and probably pre Plato as well. He just happened to be the first person that really wrote it down, which is the idea that every soul chooses to come into this world for a kind of purpose. I don’t like the word purpose because it sounds too much like doing. But with that caveat, comes here to be something, to reflect something, sometimes even perhaps to do something, but with a gift to give the world. And the argument, I think, or the way that I see it, would be that there are two purposes that are intertwined in the soul’s journey through the world.

Sharon: One is that we have as a soul to grow. So that’s a kind of individual thing. But the second thing is that we came here to offer the world a gift. It can be a seemingly very, very simple thing. Making a beautiful garden in this context is not a minor thing. It doesn’t have to be grandiose. But the point is that I do think of it like a garden. So in a garden you have all kinds of different flowers, and every flower is a unique expression of what a garden can be. And that’s what we are as humans in this lovely old tradition. Every one of us has a particular way of being human, a particular way of flourishing, a particular way of giving something to the world, whatever that might be. And the second half of life, it seems to me, is absolutely the time when we do that. So if we begin with a kind of interrogation around what is it, that gift, what is it that we uniquely bring? And again, realising it doesn’t have to be anything grandiose or spectacular. What is it that is unique to us? What have we got to offer the world? And it is unique to everybody. Which is why I liked in the book, providing the templates if you like, over so many different archetypes. Because everybody’s inner hag, if I can use that term that I use in the book, is probably very different because it’s a reflection of who you are as a unique individual in the world.

Manda: Yes. Particularly if you happen not to identify as a woman, your inner hag is going to be really different. But yes. So this brings up a lot of questions that again, probably reflect my ignorance of mythology and the past. My sense, looking at the generations that preceded us, is there’s a lot of them didn’t have the opportunity – not necessarily just because women died young; everybody died young. But because of the nature of colonial culture, that they didn’t really have a chance to explore what their gift might be. Looking around, it feels that our generation, those of us who are heading into our sixth decade now; basically the boomer generation, if we’re going to use young person narratives; are almost unique in having had the time and the space and the material input to be able, the luxury really to explore what our calling might be. And to do that in the second half of quite a long life, having either had our kids, if having kids was our thing; or having had our career, whatever that might be, to set us up with the material foundation to be able to do that. If I look at the young people now, they’re staring tipping points in the face that mean 40, 50 years from now might be a long way too late for them to begin to find their calling. And actually, they want to find it now. The young people that that I know, certainly the ones who feedback from the podcast, you know, they may be 21, but they want that calling now. They don’t want to wait 20 or 30 years. And I wonder, are there within the mythological archetypes or within any of the structures of the things that you teach, help for young people to move into a calling sooner than the second half of life. Does that make sense as a concept and a question?

Sharon: It makes sense as a question. I think as a concept it kind of misses the point, if you’ll forgive me for putting it that bluntly. First of all, I want to say that Calling is not about saving the world. Somebody’s calling might be to try to save the world. Greta Thunberg clearly is, but calling is different for everybody. So the circumstances of the planet and the society and the culture in which it operates a kind of by the by, in a way. Calling is also very much, at the risk of sounding cliched, a journey, not a destination. So you can choose to have a vocation when you’re young, which is a little bit different. Vocations sits somewhere between, you know, career choice and Calling. You can choose to think, oh, yes, I have these gifts here right now. I’m going to go out and use them in order to make the world a better place. Again, if I can put it simplistically. But Calling is a little bit deeper than that. It’s about very much becoming intimately familiar with who you are as a soul. With what the real deep qualities are, and you can’t do that when you’re young. And one of the beauties of menopause, I think, for women; sorry, that’s a little bit probably too much of a sweeping statement.

Sharon: You can get some glimpses of it, of course you can. But I think until you have been through the testing pot of life over and over again, you don’t necessarily know exactly what it is that you are made of and what survives when everything else is stripped away. And that is what the second half of life to me is kind of about. And for women, menopause does that for us. So in the book I describe it as very much an alchemical process. And in alchemy, the substance underwent many, many different processes. But one of them, CALCINATION, which is basically stripping away to the bone or to even to the ashes, what is left when everything else is burnt away. And I do think that that happens over time. And maybe some people will come to it younger and some people will come to it later, but I don’t think it’s something you find in your twenties. I think you can have glimpses of it, of course. You know, you can have glimpses of it in your teenage years if you particularly, if you’ve had a challenging childhood and difficult experiences. But it really seems to me that it is a process of maturation.

Manda: Okay. So I completely get that the alchemical process that you describe beautifully in the book is in the large part physiological that life is the way life is and we have our Palaeolithic emotions and medieval institutions and the technologies of gods; but we also have bodies that the primary of which goes back hundreds of thousands of years. And so for young people listening who may not be seeing an Elderhood happening and yet want a sense of moving through the rites of passage of their own ages and of finding a calling in a way that would prepare them for the Elderhood that you talk about, where we are in service and have found our calling. How would you help them to navigate that route?

Sharon: I think one of the things that we have to begin with is in some way helping younger people to understand that this is the route. Because obviously our culture, which is so focussed on progress and acquiring staff, doesn’t have this sense of developing our Calling, or what you so beautifully call the soul’s dance, as something that we are intended to do. It doesn’t even see it as an optional extra that one can choose to do. So we’re told that what we need to do is to acquire a lot of stuff in an ideal world. And of course most people do not live in an ideal world. Pay off the mortgage, retire at 60 or 65 and go off on world cruises or play golf a lot and then tick box, you know, done. And I think one of the main things, of course, a lot of young people are way too smart to fall into that trap. They know that there is something more, but that’s the map that the culture provides. And so you’re absolutely right to to raise that question: how do we provide a different kind of map? And, gosh, that’s a huge question. And to put it very briefly, I’d say by certainly by us providing inspiration from what we do, by making them aware, the wider culture aware, of stories which can provide inspiration and myths which can provide inspiration. By looking and educating people about the different types of calling, so that it isn’t all about, you know, what job you do or whether you get to save the whole planet, but can be something that looks on the surface to be very small.

Sharon: But none of us know the consequences of our actions and who we are and what we do. And the one thing that it has always seemed to me, that I always stress about Calling, I think, you know, that you are in line with your Calling when you stop being attached to outcome in some way. And by that I don’t mean that you stop caring about whether the world around you dies, but that you are so much living what you can do, what you love to do, what you were made to do and are here to do, that it doesn’t matter. You don’t have to count the numbers. And I did that for so much of my life. I would, you know, do guided meditations and visualisations and meet an old woman in a cave and say, How many do I have to save? And that is just the wrong question. It’s the wrong question because it doesn’t matter how many. Sometimes it’s just the one. So I think these kinds of conversations we need to be having as older women amongst ourselves, and we need to be figuring out a lot of stuff for ourselves that we can then use to draw younger people, at all stages of their life, into these conversations. So that they’re having them earlier. And there is a sense that you are going into life with the concept of a Calling and a gift to bring the world. And you don’t have to wait, you know, till you’re as old as we are, to figure out that this might be a thing.

Manda: Brilliant.

Sharon: Not that either of us have done that, but a lot of women, of course, do to get to a fair, ripe old age.

Manda: Yeah, because the dominant culture has given them other things to focus on. And I think our dominant culture also one of the unwritten rules is don’t get old. And what you’ve done with Hagitude is explore the beauty and the magic and the wonder and the yes, I want to be that. And providing an enriching, enlivining and magical role model of Elderhood, of women’s Elderhood, but of Elderhood in general. For everyone to look towards and think ‘that! I want that’ seems to me to be one of the great gifts of this book. Were you thinking towards that as you were writing, or am I projecting that on afterwards with my usual flair?

Sharon: No, you’re absolutely right. I was thinking that. I wanted people to be inspired to think that there could be something quite magical after menopause, if we just take that as a, you know, a handy midpoint for for many people or change point for many people. I wanted for people to feel that this was not the end, that they didn’t have to become invisible if they didn’t want to be. Or they could become invisible if they did, depending on the nature of their inner Hag; but that this wasn’t inevitable. So yes, I wanted to inspire, but also without being too gloomy. I also wanted people to understand that certainly I think as you enter into later stages of Elderhood, it is a process also of continually letting go of whatever it was that you thought defined you. There was a woman who wrote a comment, I think she said she was in her seventies. On a Facebook post that I made about Hagitude over the weekend, who said, A lot of people who are younger don’t realise that when you get into your seventies or whatever age it might be for you, for some people it’s very much older. That everything begins to turn to the process of just physically keeping going, because everything’s breaking. She didn’t say it quite that way, that’s my words for it. And so everything kind of narrows down to a very, very tight focus, not where you’re concerned about your, you know, your own physical health, but where the options that are open to you are constantly narrowing over time until you pass through that door.

Sharon: Now, a lot of women manage to stay fit and healthy way into their seventies, eighties and beyond. But for most people, there will be the sense of physical difficulty and physical decline. And that kind of that means that part of the beauty of Elderhood is to find a way to allow that focus, that very narrow focus to happen, that turning in over time gradually to the essence of what is left, and to also see that not as something to be dreaded, but something that needs a little bit of preparation, psychologically, and maybe a little bit of managing. So, yes, there’s the inspiration and it’s wonderful. But there’s also developing the skill set, if I can use that word, to manage the really tough stuff that can come along with Elderhood as well. And that is, you know, very much what my own situation was about, I think, and that passage through illness and looking death in the face was very much about trying to marry those two things. On the one hand, inspiration, yes, I’m all for the journey ahead, but on the other hand, there’s this really difficult stuff that we have to marry.

Manda: Yes. So we’re heading towards the end. We’ve probably gone over it. But this is too huge to let go. And it was somewhere I wanted to get to, because you’ve said to me in private and you say in the book that given the chance, you wouldn’t not have the physical bomb that you said took over your life. And you were for a while and possibly still are – we are all staring death in the face. We are all definitely going to die. But there are certain physiological, physical, pharmacological effects you had when you were on chemotherapy that make death feel much closer. And that seems to me, again, a rite of passage. So many of the shamanic initiations involve either burials or, you know, nine days, nine nights hanging from the tree. All of the things that bring death right into focus and the people who survived were the ones who went on to be the tribal shamans. And the pass rate was not very high. And you’ve had that very close brush with death and would not undo it. Can you give us a little bit of the sense of how the world feels walking in the shadow of the valley of death, as you said?

Sharon: It’s very hard to put it into words. It’s not so much it’s hard to put into words, it’s difficult to explain it. And all I can say is that it’s kind of like a, just like a shift. It is like a veil has been torn away so that everything is more filled with meaning. And I don’t mean that in a kind of cliched sense of, oh, you know, I almost died so now I appreciate the world even more. And that isn’t a cliche. That’s also very beautiful. It’s not that, it’s just that it’s as if another layer of reality kind of exposed itself, so that it seems to me that you can only – and again, this is not a particularly profound or original thought, but when you experience it, it seems to be for you. You can only really live in the presence of death and in the acknowledged presence of death. And, you know, I used this example. I think I wrote about it in the book, I can’t remember how much of it I put in the book now, but the first experience I’d really had with death was when our beautiful dog Nell developed exactly the same type of lymphoma that I eventually had, in exactly the same place on her neck. Had pretty much exactly the same kind of treatment. So she very much kind of walked ahead of me in that. And we were told that if she didn’t have chemotherapy, she would live maybe 4 to 6 weeks. And if she did have chemotherapy, she would live for a year.

Sharon: Now, for clarity, she’s running around five years later chasing sheep in the fields and she is my inspiration. But that was the first time, and I know it sounds unusual, but that’s the first time that anybody really close to me had faced death. My mother hadn’t died at that time. My father had died. But you know, I hadn’t been close to him since he left when I was two. So nobody really close to me had died. And that was the first time I’d actually encountered death in that way. And I said to a friend of mine that it felt as if death had walked uninvited into my house and sat down at the table. And that really made me very cross. Through my own process of going through lymphoma, I felt as if, okay, I have to invite death in and give her a glass of wine and just find a way to not just to tolerate that presence, but to see what it has to offer us in the midst of life. And I am going to struggle to put any more words around it than that. But it is very much a question of just, if every waking moment is lived in the knowledge of death or in the presence of death, then everything becomes more beautiful and more meaningful. It’s the opposite of what you might imagine. you know, it’s not filled with gloom and desperation.

Sharon: But I think for me, the reason why that is the case is because I do feel that I am absolutely in the flow of my own calling. And if I weren’t, if I thought that I hadn’t quite found my calling yet or that I didn’t know that, you know, I’d achieved perhaps some of the things that I might have come here to achieve, that might be very, very different. But what it did, the whole process, is it made me really think about, okay, you know, who are you? What is your calling? If you if you were to die tomorrow, would that be okay? And it was absolutely okay. I did not want to die tomorrow, but it’s just like, okay, no, it’s not about being self satisfied with what you’ve done and thinking that, you know, you’ve got nothing else to learn. I’ve got lots and lots of things to learn and hopefully more transformations to go through. But it’s just that sense of okay, that would be okay. And there’s a kind of peacefulness in that, that just settled me. In a word that my great aunt used to use when I was a fractious child: why can’t you ever settle? I don’t mean in a way of being quiet, but just like that kind of Okay, there we go. This is all right now. That’s fine. Let’s just get on with it. Let’s get on with the story.

Manda: That’s beautiful. There was so much more I wanted to ask. We haven’t talked about Granny Weatherwax and I really wanted to, but it feels actually like…

Sharon: Me too.

Manda: But that is so beautiful. Because there is going to come a day for all of us where tomorrow is the day that we die. There’s a beautiful book called Hanta Yo by Ruth Beebe Hill; because Hanta Yo meant Today is a good day to die. And it was what the Warriors, Lakota Warriors would say as they staked themselves out to face the enemy. And today is a good day to die. Whenever it is, there will be the day; provided we have lived. And it seems to me that you are able to express that in the book, in what you just said and your other writing, that sense of the imminence of death creates or perhaps helps open the doors to or lift the veil, as you said, to the rich magic of life in ways that nothing else really does.

Sharon: That’s what creates the meaning. Yeah.

Manda: Yes. Yes. I wonder, because neither you or I have gone through childbirth whether that takes the women who don’t go through the medicalized ‘let’s anaesthetise you so you’re completely unaware of the entire process’ whether proximity to the entry into life in that way has a similar effect to the proximity to the exit from life. Only that I find that I become very much more aware of death when I’m sitting with a foaling mare or a lambing ewe. And I have a friend who has been a midwife into death, and again, sitting with other people and being there at the moment when somebody crosses over seems to be another way of lifting the veil.

Sharon: Yes.

Manda: Let’s just very briefly talk about Granny Weatherwax, because we can. Partly because also I think Terry Pratchett, who is no longer with us, which is a great, great regret, also was one of those people who managed to create a sense of death as real and yet something to be welcomed. Anything that talks in block capitals all the time and has a horse called Binky can’t be all bad, and is there to be enjoyed. Just before I get to Granny Weatherwax, did you find other mythological or literary ways of envisioning and embracing death? You’ve mentioned inviting her in for a glass of wine. Were the things in the folktales and the mythologies that helped you to come to a deeper understanding of death? Or was it just a process of what was going on?

Sharon: Yes, probably. I mean, we clearly have a lot of harbingers of death in Celtic mythology. We have the best known of them being the banshee, the Bean Sidhe in Gaelic mythology, the washerwoman at the ford as well. So we have death personified almost always in our mythology as an old woman, and I could go with that. There was a time when I saw death as maybe a middle aged woman, a little bit of silver in her hair. But I would say no now; it’s definitely a black dressed old woman. And that probably would be derived from characters like the Banshee, the Bean Sidhe in Gaelic mythology, yeah.

Manda: And the crow. Everything associated with crows was always associated with death for obvious reasons. They’re carrion birds in their blood. And you again, in the book, you have a real affinity to crows and hooded crows and the other corvids the magpies. So did they make any different of an impact as you were brushing closer to death?

Sharon: Well, I think I’ve always associated crows and Ravens, of course, with the Irish goddess, the Morrigan, who was a shapeshifter who took on either female human form or Crow/Raven (We don’t know which, because of the language discrepancies) as she pleased. And so I always would see death probably as somewhere between the Morrigan and the Cailleach. So yeah, birds generally speaking, to me, I associate with death. The birds that I’m drawn to, just purely by chance, everything from crows and other corvids through to herons who were guardians of the gates of the other world, in Irish and Welsh mythology. So yeah, probably.

Manda: Fantastic. Yes. I remember in one of the very old Rosemary Sutcliffe books that I read, the Spear of the Warrior had heron feathers around its neck. And that was always, that kind of sense of and that which dies is thereby carried into the other world.

Sharon: Right

Manda: So just towards the end, Granny Weatherwax. You’ve got this beautiful quote of witches and magic. And I love that you’re debunking the whole the witch burnings were millions and it was the removal of the old pagan religions. I love that people need to read the book, I think to go into the depths of why that isn’t true, but that the underlying truth is actually darker and harder. But then there’s the other side of our witch mythologies that Terry Pratchett did so beautifully. And Granny says: It’s all power. It’s all… Granny paused and dredged up her favourite word to describe all she despised in wizardry: jommetry. It’s the wrong kind of magic for women is wizard magic. Witches is a different thing altogether. It’s magic out of the ground, not out of the sky. And men could never get the hang of it. And the fact that a man wrote that, has always seemed to me amazing. Terry Pratchett was in many ways extraordinary. Just say a little bit towards the end about the wonder of Granny Weatherwax and what kind of a role model she could be.

Sharon: Well, I adore Terry Pratchett for those witches and yes, for his for his character of death. I mean, that is astonishing. And what was more astonishing, is the way which I also describe very briefly in the book, that they were all associated with the geology of the places that they came from. You know, they literally were women who were products of the land. And to me, I think that is the first thing that I really loved about Pratchett’s witches. That Granny Weatherwax is a granite witch, she couldn’t be anything else, you know, you couldn’t displace her to chalk. She is a granite witch through and through. And so she is kind of very much a product of her environment in the way that the Cailleach was associated, literally kind of almost immanent in it. And so I think for the first time I saw a fictional rather than a mythological figure, where somebody had taken that idea and actually given it flesh. And I am very much a granite person. I don’t do well here where I am on sandstone and mudstone. I can’t quite get to grips with it. I’m trying very hard, but it’s proving to be a challenge for me. I like Lewisian Gneiss, which is the second oldest rock on the planet. I like granite, I like quartzite. I like the really hard, difficult, bleak stuff. And Granny seems to me to be a product of that, so that she was not an easy woman, clearly, to be around. And yet she had the most integrity, I think, of any fictional character that I have ever come across.

Sharon: And to see that marriage of all of those qualities; the integrity, the, you know, sense of humour, the fierceness, the I’m not going to budge if I think it’s right. And that absolute ability to be part of the land. And then of course, her borrowing. Where she would effectively do shape shifting journeys, she would take on she would borrow the bodies of birds or whatever animals she wanted to. Just seem to me, for me the most perfect picture of Elderhood. I like the fact, you know, when I grew up, the old women spoke their minds. They weren’t always kind, but they were always right. And I think that we need to be able to deal with that as a society. And Granny, again, is one of the truth tellers that is never gratuitously unpleasant or rude or whatever. But just feels the need to speak the truth when the truth needs to be spoken. So all of those things and the fact that she is really, really funny just make me adore Granny Weatherwax. She is my role model. I will never be Granny Weatherwax but I can aspire.

Manda: Yes, I think so close. Because she’s so wise and you are so wise and this is such a beautiful book. And if any book and concept and the course that you run from it, is ever able to rid our society of its fear of age and death and look up to the wise people who have gone through the alchemical process and come out the other side. Then this is going to be the book. So we do have to stop there, way over time. Sharon, thank you so much for coming on to Accidental Gods and for writing this book. It has been a joy to read and I will treasure it and read it again. Thanks you.

Sharon: Thank you so much. It’s been a pleasure to be a guest for a second time. Thank you for inviting me.

Manda: And that’s it for another week. Enormous thanks to Sharon for weaving the wonder of the book that is Hagitude and then for engaging with such heart and authenticity and integrity and intelligence and wisdom, with all that we explored. And I do love that we managed to get to Granny Weatherwax in the end because she too is one of my all time favourite characters. I have put links in the show notes to the Hagitude website, where you can find details of the book and the podcasts that Sharon has done about Hagitude. And I’ve also linked to her main personal website, where she runs other courses, and also to the Sunday Times Review with Christina Patterson, which was spectacular and lovely. And if you can get behind the paywall, well worth reading. So I definitely recommend that you head off, read hagitude, buy it for any of your friends who are heading into the second half of life, because all of us need to understand what it is to step into Elderhood.

You may also like these recent podcasts

Seeds of Hope: Cultivating a Future of Flavour and Resilience with Sinead Fortune and Kate Hastings of the Gaia Foundation

Our guests today are two remarkable women who bring energy, commitment and deep thought into building communities of food both nationally and internationally, in bringing ancient local species back from the brink of extinction and rediscovering, or in some cases, building anew the local technology that’ll help to rebuild the communities of place that have been focused on food for millennia and only recently been eroded. They are both masterful storytellers, bringing enthusiasm and the spark of hope to something that touches us all.

Finding a Cure for Civilisation: Delving Deep into the Roots of Being with visionary and shaman, Drea Burbank of Savimbo

For those who are ready to stand with the guardians of our planet’s remaining wilderness, this episode is an essential listen. Join us as we explore the profound connections between human healing and planetary health, where the fight for nature’s rights is a fight for our collective future.

River Charters, Net Zero Cities and BioRegional Banks: Creating a Life-Ennobling Economic System with Emily Harris of Dark Matter Labs

Emily unveils the bold concept of life-enabling economics and the radical aspiration of establishing bioregional banks — a system where money is no longer a mere transactional tool but a means to foster a thriving web of life. From the Findhorn watershed initiative to the Sheffield River Don project, Emily details practical steps towards making these ideas a reality, including the creation of relationship registers and multivalent currencies like ‘river coins’.

Dung Beetles, People and helping the Keystone Species with Claire Whittle, the Regenerative Vet

A moving and deeply authentic conversation with Claire Whittle about her journey from traditional large animal vet to advocate for the human capacity to engage with the natural world, for our ability to become a positive keystone species and for farming to become a lower stressed, lower input, far more wholistic experience than it generally is.

STAY IN TOUCH

For a regular supply of ideas about humanity's next evolutionary step, insights into the thinking behind some of the podcasts, early updates on the guests we'll be having on the show - AND a free Water visualisation that will guide you through a deep immersion in water connection...sign up here.

(NB: This is a free newsletter - it's not joining up to the Membership! That's a nice, subtle pink button on the 'Join Us' page...)