Episode #130 Connecting with Power: How the media could reframe our world – and why they must – with Donnachadh McCarthy

How do we bring the world’s media on board with the climate and ecological emergency? What would happen if they became the fourth arm of the climate movement? Donnachadh McCarthy, journalist, columnist, author and long term climate activist explains why this is the single most urgent action we can take.

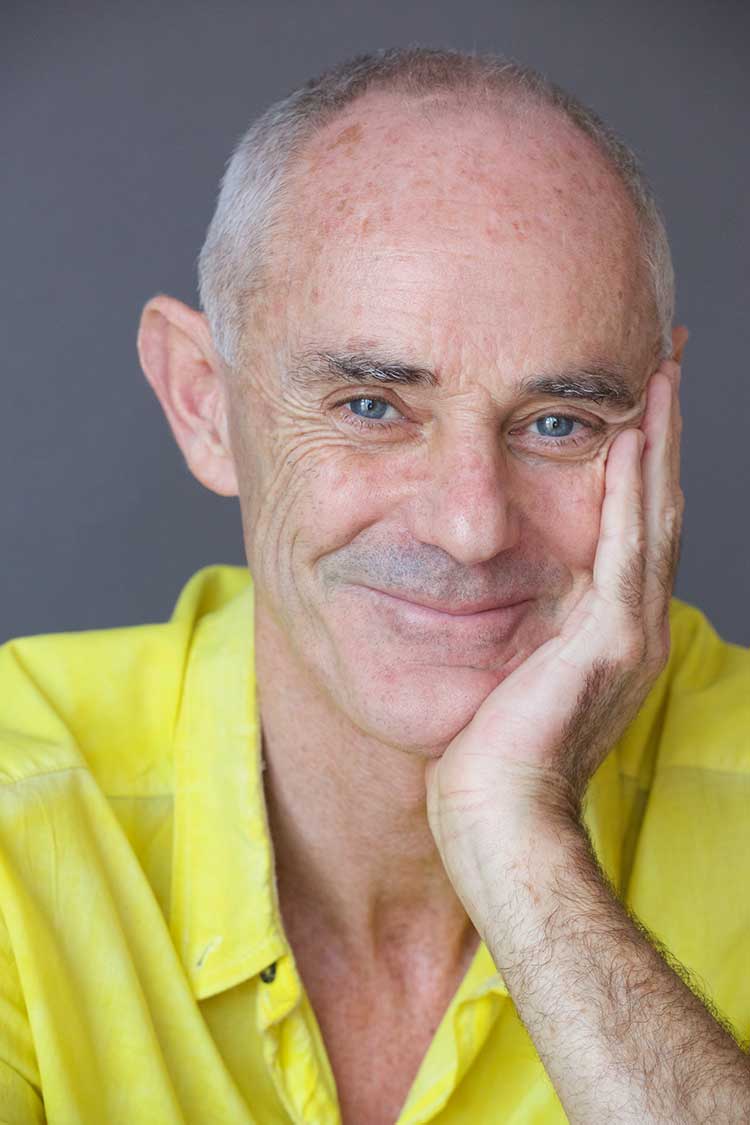

Donnachadh McCarthy is a professional eco-auditor, author and environmental campaigner. He is a former deputy chair of the Liberal Democrats and served on the board of the party for seven years. He is now not a member of any political party and enjoys working with people in all parties or none to address our common environmental crises. He is a former columnist with The Independent and has had articles printed in the Guardian, Times, Ecologist, Resurgence etc.

He is the author of Saving the Planet Without Costing the Earth, Easy Eco-auditing, and The Prostitute State – How Britain’s Democracy has Been Bought. He is the co-founder of the successful cycling campaign group Stop Killing Cyclists. His environmental consultancy 3 Acorns Eco-audits helps deliver the Corporation of London’s City Bridge Trust eco-auditing programme for London charities. His Victorian home in Camberwell, was London’s first carbon negative home. It has solar electric and solar hot-water, a Clean Air Act compliant wood-burner, solid-wall insulation, rain-harvester and composting toilet.

In this rawly honest conversation, he lays out the reasons why he believes that if we are to survive the Great Derangement, the media must become the fourth pillar of the environment movement. Along the way, we discuss his visit to the Yanomami and how it changed his life, his political experience at the rotten core of Britain’s corrupt political system, and his swan-dive into a new future on the stage at Covent Garden. Join us to reframe the setting of your intent.

Episode #130

In Conversation

Manda: My guest this week is one of those with such a solid, strong, clear intent for building that vision that simply talking to him was an inspiration, as you’ll hear. Donnachadh McCarthy was a dancer with the Royal Ballet until a life changing accident, that saw him become a political activist, an environmental activist, an author, a journalist, climate columnist for The Independent. And now he’s one of the foremost guests that media stations from GMB TV through to Channel four with everything in between invite to come and talk about environmental issues and the activism around them. He’s written three books: Saving the Planet Without Costing the Earth; 500 Steps to a Greener Lifestyle and then Easy Eco Auditing; How To Make Your Home and Workplace Planet Friendly. And he’s basing this on his own life. He wrote a post on Facebook recently celebrating the fact that his own home has now become carbon negative. He pours more power back into the grid than he takes from it. I found him with his 2014 book, The Prostitute State: How Britain’s Democracy has been Bought, which radically changed my understanding of the political process in Britain and around the world.

More recently, he’s been an XR activist, right at the front of the work to try and change the way the media perceives and then represents the climate and ecological emergency. I could go on. Donnachadh has been one of my heroes since I read The Prostitute State, but I’ll stop now and pass over to the interview. So people of the podcast, please do welcome Donnachadh McCarthy.

So, Donnachadh McCarthy: a very long time and a wonderful hero of mine. Welcome to the Accidental Gods podcast. I’ve been reading you for a very long time since I was an activist for the Lib Dems, which is one of those things that I’m almost ashamed to say. But it was a very long time ago. I was very young, I didn’t know anything. And when I read your book, The Prostitute State, it helped situate me where I was and understand why I was feeling so uncomfortable being an activist for the Lib Dems. This is probably losing me listeners by the score, because I’ve never said this on an open mic before. But anyway, my past is quite different. And so, I’d really like you to tell listeners how you came from being a dancer with the Royal Ballet, which I gather you did quite late, and you set an intent and you got there; to being climate columnist for The Independent and the person who wrote ‘The Prostitute State.

Donnachadh: You’re talking about 30 years.

Manda: Yeah. There you go…

Donnachadh: Thanks, Manda. That’s a nice challenge to start off the interview with. Well, I suppose let’s start at the start. I was a dancer. I started late, as you mentioned. I was a medical student, spent four years doing medicine, and then I decided I didn’t want to be a doctor and met a woman who was doing ballet and said, is there any place a guy my age could do a class? And so she said, yes, try the Court Ballet Company’s women’s keep fit class – they do some ballet in that. So I went down and did a class with these office, girls office women and decided I loved it. So worse than Billy Elliot, I ended up doing classes with like, here was this 20 year old doing classes with ten year olds, little ballet darlings. And anyway, after a year, I got a scholarship to the Irish National Ballet, which is nuts. And then two years they said, Look, you’re 21, you’re doing amazingly well, but you should think of a different career. So I walked out the door, rang the Dublin City Ballet, asked for an audition and got it. And so I was working professionally within two years, which was completely nuts. The writing was on the wall a couple of years later with them, so I said, I’d come to London to do more training. And when I started doing ballet, I set myself a task of a dream of dancing, at Covent Garden.

Donnachadh: Because I wanted to test…I know your listeners are used to a lot of talk about shamanism and meditation and a lot of the spiritual teachings, say that in beginning comes the word, the words made flesh. And I wanted to test that. So, my beginning word was: I want to dance at Covent Garden. So I go on to say, okay, let’s see if all this mumbo jumbo works!

Manda: That is so cool.

Donnachadh: And so seven years later, I was doing an audition for the Royal Opera Ballet, with 500 of us in the studio, and they divided into groups of 100 and then groups of 50 and then groups of ten. And eventually we had to do these moves across the huge studio at the Opera House by ourselves. And so I got selected and I got down to the last 12 men and I got to dance with the Royal Opera Ballet. And so all that mumbo jumbo worked. In Beginning was the word and the word was made not flesh, but the word danced.

Manda: I have a question. Were you setting that as a clear intent on a daily basis for seven years? Because when I read the books about setting intent and the whole manifestation thing, which always leaves me feeling a bit strange. I think there’s a lot of holes in it. But, you know, ‘I want to dance at the Royal Ballet’ is clean and clear and physically possible. And you did it. Was it, did you meditate? Did you spend an hour a day? This is where I’m going? Or did you just set it as a single intent and go for it?

Donnachadh: I set it as the intent and kept setting it as the intent.

Manda: Right.

Donnachadh: It’s actually supposed to be impossible, because you are supposed to start ballet at ten or 12. It does take seven years to get into the body at least, and I started at 22. 21.

Manda: By which time most dancers are retiring because they’ve broken everything.

Donnachadh: They retire around 28. So, you know. And it was an amazing privilege, really challenging spiritually, mentally, physically. It changed everything. And in some ways, I think in some ways that prepared me. A lot of what I do as a as a campaigner is performing. You know, you’re talking you’re communicating. Whether it’s in books, whether it’s writing, whether it’s interviews, whether it’s at a rally, whether it’s at a protest, it is a form of communication. And in some ways, I feel a lot of the stuff I learnt as a dancer prepared me for what ended up devoting my life to for the last 30 years.

Manda: And I’m guessing also that this is an embodied performance. In a way that, say, me standing on a stage reading a book is not necessarily an embodied performance. But dancing; it’s your whole body and, the way you did it definitely, also your whole spirit. And that this must carry through, too, is what I’m thinking. That that is a very unique combination to get that amount of physical and energetic and spiritual energy into alignment. Is that a thing that’s common with all dancers? Or is that something that you brought to it because of your path?

Donnachadh: I’d say it’s what I brought with my path. People come to ballet usually quite early, and so for them they don’t have a very wide life experience, a lot a lot of dancers. Because it takes such total dedication. I mean, I think it’s one in 10,000, something enormous. One in 10,000 girls studying ballet will do dance professionally.

Manda: Wow.

Donnachadh: The odds are enormous of not ever doing it professionally. So therefore, you have to devote everything to it. And of course, because I had lived a different life and had done some self-development and had engaged with some spiritual self development and courses and challenges prior to that. A lot of personal stuff to deal with and work through and forgiveness exercises, for me and for people in my life, both ways, obviously. So, yeah. So I had that gift in a way by starting late.

Manda: Yeah. If we had more time, I would really be interested in exploring why you decided not to be a medic. Not that I think anyone necessarily would want to be a medic. But you had thought you did, and then you changed. We might come back to that, but I think time is of the essence for both of us. We’re trying to get within our hour. So you were dancing at Covent Garden. You fulfilled that dream. And within a relatively short span of time, you became a political activist and climate columnist for The Independent. Can you talk us through the process by which your life turned on its head?

Donnachadh: Sure. I became climate columnist much later. I had to gather the experience and knowledge and traumas and positives first. The transition from being a dancer to a campaigner was quite sudden and it looked as if the universe came along and just gave me a push, literally. I was dancing. I was in the dress rehearsal. I had a lovely little role where I was centre stage at the Royal Opera House. There was a 100 chorus behind me. It was dress rehearsal for William Tell. It was a full orchestra and I was standing on the guys shoulders, being a little ballet boy, waving at people. And then I had to do a swallow dive, fling myself off into mid-air looking at this beautiful theatre in front of me. And four guys catch me. And then one day in the middle of this dress rehearsal, they missed. So I landed from 12 foot. No hands, hands wide open. The first I knew about it was, whoops, there’s been an accident. Whoops. Somebody has been injured. Whoops. I think it’s me.

Manda: Oh, Donnachadh, that must have hurt.

Donnachadh: It was quite an experience. And I’m very lucky I didn’t die or have a broken back. I survived. And I actually had what felt like an out-of-body experience in the hospital. And my friend, jeez, it’s interesting how many things are coming up in this interview, because you said your audience is used to shamanic work. My friend came with me to the hospital from the opera house and he said I looked on last legs. I was completely wiped out on the stretcher. But I was doing my first major role with a small company up in Yorkshire around a month later. And it was Giselle and it’s a beautiful spiritual ballet and it was the ultimate role I wanted to do. And I was not going to let this stop me. So once I was on the bench, I felt as if I sat up out of my body and I just went, No, no, no, no. I’ve got too many things to do. No, no, no, no, no. I’ve got too many things. And back in I went. So they wheeled me into the X-ray room. And I decided at that stage I wasn’t very positive about Western medicine. I’m now much, much more balanced. And I started to visualise that the X-ray machine was pouring, healing into my body. Positive X-Rays!

Donnachadh: And so I did that meditation in the X-ray room and they wheeled me out. My friend looked at me and went, “what the hell happened to you? You went in looking as if you’re dying and you’ve come out looking alive!”.

Manda: Oh, good man. You see, we should all be doing this. But what did the X-rays look like?

Donnachadh: Well, I hadn’t broken my back. So I was actually up on the guy’s shoulders doing it three or four days later. And I had every single kind of therapy you could possibly imagine. And I ended up doing the role. I was not going to let it stop me. But to make a long story short, one of my therapists, she was a spiritual homeopath. And one day she said to me, “Donachadh, I’m going out with a group of alternative practitioners to the Yanomami. But somebody dropped out. Do you want to come?” So I bit on my fingers and said Yes!

Manda: But you didn’t have any obvious ballet roles coming up in the next month.

Donnachadh: You know, I was a ballet dancer, not a jungle explorer, but I thought, you know, you don’t get an offer like that. So anyway, I accepted the invitation, a lot of a long story short. I spent a month in total in the Amazon, heart of the Amazon. And ended up by myself with the Yanomami Indians. And saw from my first hand, the destruction of the rainforest and I became emotionally aware of the destruction our so-called civilisation is carrying out. There were 6 million indigenous people in the Amazon when our civilisation arrived. It’s now less than 600,000. And that massacre continues day after day. And it broke my heart. And I came back to London thinking, What can I do? And I felt that working on rainforest issues felt like Sisyphus, if you know the story.

Manda: Pushing boulders up hills.

Donnachadh: For eternity. And I felt, you know, there’s no point in pushing back the bulldozer if you don’t actually address the reason why the bulldozer is coming.

Manda: Right.

Donnachadh: And so I took the decision that… I just found it too painful anyway to be involved. Because it’s horrible to say, but I just felt there wasn’t any hope.

Manda: Oh, Donnachadh…

Donnachadh: For these people. That our civilisation was had killed five and a half million of them and was going to kill the last half million no matter what we did. And that continues with Bolsonaro to this day

Donnachadh: And emotionally, it was, I sound wimpy, but I just…it was too painful. So I decided to try and get to the other side of the bulldozer and try and do my little bit to stop Britain being a destructive consumer society, which is what is driving the bulldozer at those people. Our lifestyles: our businesses, our government, our individuals, all three. And so I’m a Gandhian in so far as you know, be the change you wish to see in the world. So I decided that I would do my best to green my lifestyle. I thought that was the most important thing I could do from a spiritual point of view. And in those days, there was no information about how to live green lifestyle. I just had to go everywhere I could possibly to try and drag the information, pull it together. So those days, absolutely I didn’t have much money as a ballet dancer. In fact, I had none in the bank as a freelance dancer. But I decided each time I went shopping, I’d buy one thing organic. And so I bought a jar of organic ketchup. And that started my journey to being greener.

Manda: Organic ketchup is a thing?

Donnachadh: One little jar of organic ketchup. And fast forward to today and my house is carbon negative, which was London’s first carbon negative house. It was the first house to sell green electricity metered to the grid in 1998. First house to ask for planning permission for a turbine, that didn’t work. But it’s got solar panels, solar electric, solar water, triple glazing, solid wall insulation, composting loo, rain harvester, grow some veg and fruit and yeah. So I get around one half a wheelie bin of waste a year of non recycled waste and I don’t have any gas bill anymore and my electricity bill is negative. And my water bill is just around £5 over the standard charge. I don’t fly for holidays and I don’t have a car. I’ve never had a car. Now I know for some people, talking about that presses buttons, because they think all the attention needs to be on the government and on businesses. But I come from a really clear position. I read so many articles in The Guardian; every six months there’s another person rants We mustn’t talk about personal behaviour or personal responsibility must only talk about the government. And that makes me, as a liberal, small l, I will see both (one of the challenges of being a liberal is I always see both sides) And so both sides will often think you are wrong because you’re pointing out what’s wrong about them.

Manda: Yeah, it gets into a big dark spiral quite quickly.

Donnachadh: My view is that my having a negative carbon home and lifestyle, is not going to save the world. But I believe as a person, it gives me much more power to my voice, as an individual. Because I have the moral authority of trying my best. I’m not perfect. Nobody is. But I’m trying my best to make my footstep as light on this planet, so the next seven generations will not be devastated by what I am doing. And I think that makes my voice stronger. And I think in many ways it’s given me a voice that people have been willing to allow me to express, whether through my books, my writing, my journalism in the Independent or my work on many radio and TV programmes. It comes from that, I think, grounding in moral truth. And so when people say personal action doesn’t matter, it worries me, because how are we going to have the moral authority to get the government to change the banks, to change the media, to change the oil companies, to change, if we’re saying ‘you must stop what you’re doing!’ And I’m still eating meat, flying on holidays, driving my four by four around, it’s just not going to work. Two Jags Prescott. His aim was he had failed if he hadn’t brought down transport. He had two Jaguars. He didn’t break down transport, you know. Surprise, surprise.

Manda: Yeah. Yes. I suppose the counter-argument that I hear from this is that BP and the other big oil companies threw astonishing amounts of lobbying money into creating carbon calculators for individuals, so that we would all be focussed on trying to narrow down our own carbon footprint by another 10% per year. And we would be ignoring the wider picture. And given that we are endeavouring to create total systemic change and that means keeping as broad a view as we can and moving forward on as many fronts as we can. Then I imagine that the important point is that we do everything. That we not simply focus on one thing, whatever that one thing is, and that we work on our broad view. Does that make sense to you?

Donnachadh: Yeah, I remember Satish Kumar teaching the two legged path. I think that applies to environmentalism as much as it does to any other aspect of life: the spiritual aspect and the practical aspect. And for me, as an environmentalist, as somebody who is demanding change or requesting change from those in authority, I think spiritually it is crucial that I’m walking the second leg, which is that I’m doing it myself. I think the reason why Gandhi was so inspirational for so many people is that people saw him walking the talk. He didn’t arrive in London in a suit and top hat. Yeah, he wore his dhoti. And so when I arrive at an interview with the BBC, I arrive on my bike.

Manda: Right.

Donnachadh: It’s the same service. It’s part of the path. And it’s really important for organisations and individuals and campaigning groups. You know, I remember, you talk of Lib Democrats, you know, I brought this to the Liberal Democrats, you know. I said you say these are your values, but this is what you’re doing. And so I spent a lot of my time in the party, being that… It was a pretty horrible role. I was described by the chair, the president of the party, as the conscience of the party. Because I was simply saying, well, you say you wanted an elected upper chamber, so why aren’t we electing our nominees to the Lords? You say you want to look after the environment, so why aren’t you using recycled paper? Or you say you want to clean up the corruption, so why are we selling peerages? And so this is crucial. You know, it’s crucial. I think it’s part of my core DNA is to challenge hypocrisy. Not because it’s a smart thing to do or clever, obnoxious thing to do. It’s because it’s actually, if we want to be effective to implement what we want to do, we must be doing it ourselves.

Manda: Brilliant. Yes. Okay. That’s landing. And what you’re proving because you live in London is that you don’t have to live in a straw bale hut off the west edge of Wales and be completely off grid in order to have a carbon negative lifestyle, or at least as close as we can get within the current system. So let’s take a very brief hop forward. I just want to take a couple of minutes to look at your political career, because reading The Prostitute State really did reframe my politics for me, and then we can move on to what’s most alive for you at the moment. So my memory of the book is that it opens with this executive meeting in which Paddy Ashdown, the then leader, is saying ‘If the motion proposed by Mr. McCarthy passes, I will resign.’ And the motion proposed by Mr. McCarthy, which sounded perfectly sane to me, was that Lord something, hyphen something else should not be Paddy Ashdown’s Senior Political Advisor, which is to say setting the entire political strategy for the party, while being on the board of Rio Tinto zinc. And I think why is that not in the front page of the Guardian every day? And the motion proposed by Mr. McCarthy did not pass and Paddy Ashdown did not resign. So first of all, do I remember it right? And second, just tell us a little bit about how that came about because it just… Every time I think about it, it does bad things to my head.

Donnachadh: Well, I suppose it’s when I came crashing into what I call The Prostitute State. Which is how I’d say that Britain’s democracy has been bought, it’s been hijacked. And we think we live in a democracy. We think we support political parties. But after seven years on the board of a party, it’s very clear to me, that having experienced it right at the top of one of the smaller political parties, that our system is rigged phenomenally. And very clearly. And that’s why, after I left the Lib Dems, after 12 years trying to deal with them and gave up in despair, having, you know… We’re jumping around a lot, but…. We suddenly arrived in the Lib Dems. I think it might be just helpful to explain how I arrived there. I came back to London, decided to live a green lifestyle, found out my local park was going to be built on. And I thought, I can’t defend the rainforest from being built if I don’t defend my local wildlife site, my local park being built on. So the council had proposals to remove the open space protection from the entire park, which is 150 acre park, in Peckham, Camberwell, South London. And they were going to sell around 13 acres of it and build five storey indoor leisure centres, etcetera, etcetera. So I got involved and took a year off work and ended up, just woke up one day and I was an environmental campaigner and no longer a ballet dancer. So the local Lib Dems, saw I was an active campaigner and so they invited me to join them and become a councillor candidate.

Donnachadh: And at the time a lot of the what the Lib Dems stood for, still stand for, I quite agree with, if only they would actually seek to implement it. But you know, I do like the constitutional reform. I did like the commitment to ending corruption, I did like the commitment to the environment. And so I said, well, might as well join them. Because at the time the Greens had just got 15% in the European elections and got no seats. And I thought we have to have constitutional reform and PR if we’re going to get the environment to anywhere in the Britain’s political system. So I joined the Lib-Dems, ended up becoming elected as a councillor in Peckham, for the first time anybody other than Labour was elected. For a really huge estate, inner city council ward that contains the Aylesbury estate, one of the largest council estates in Europe. And I set myself three promises. I promised them I would try and do my best to bring down crime by half. Promised to try and stop them spraying poisons on the estate – they were spraying glyphosate everywhere around the state and on parks. And thirdly, I would try and stop the park being built on. And in my four years of the council I did all three. They were my intentions. Again, there is a word, the word.

Manda: Set clear intent. Go for it. It’s the foundation of humanity: setting clear intent.

Donnachadh: And so we got crime down, not by being punitive, but by pure community politics; getting the police involved, playing football with the kids, making sure design was crime down, to make sure that women didn’t have to walk through doorways that they couldn’t see through. And we brought it down amazingly and so it was actually written about as a national strategy. Secondly, we got the glyphosate banned right across the borough in ’94.

Manda: Well done.

Donnachadh: So all the parks and all the council estates and all the streets, the council agreed to stop. And remember I was an Opposition Councillor, so getting this done as the Opposition and then finally we managed to stop the park being built on. I think 49 different, 50 different campaigns to stop the park being built on over the years and we won 49 of the 50. One small building got built on it. Anyway, so I became a councillor and I got a letter from Survival International who I used to be a member of, because trying to support indigenous people’s rights. And their process was that you write, they send you a letter to write, to whatever head of government who’s trying to trash some indigenous people’s rights. And the Amungme people in Indonesia at the time of president Suharto, they have a religious belief system very like Christianity: when you die you go to heaven. But their heaven was the top of the local mountain and so it was very holy to them. It contained, for them, the spirits of their past ancestors. And Rio Tinto was coming along and they were going to chop the whole mountain off and turn it into a huge copper mine. So something in the back of my mind went ping and I went, Oh Lord Richard Holme, Rio Tinto Zinc… And I remembered that the head of Paddy Ashdown’s election campaign was Lord Richard Holme, who was a director of Rio Tinto Zinc. Because at that time, and still, to a certain extent, a lot of the major corporations appoint somebody from the various political parties to be on their board. Rio Tinto Zinc, unusually had somebody from all three parties, not just from Labour and the Tories.

Manda: Just cover all the bases, eh.

Donnachadh: Yeah, usually. So they major on Labour and Tory and occasionally throw in the Lib Dem. And you’ll see this right through the oil industry and nuclear industry. You’ll see they’ll hire people from Labour and the Tories to enable them facilitate their hijacking the political system. Anyway, Rio Tinto Zinc. So I thought, well, I’d be a hypocrite if I write Suharto, when the leader of my own party has appointed somebody from Rio Tinto Zinc. So I decided to do something about that, rather than write. So I wrote to Paddy Ashdown and said, ‘ Rio Tinto Zinc is condemned around the world for its environmental destruction. It’s the largest private producer of uranium, nuclear rheanium, and it’s been condemned for human rights abuses across the world. Our general election campaign is about anti-nuclear, pro-human rights and pro-environmental protection. You cannot be spokesperson – Richard Holme was the director for external affairs, i.e. their spokesperson. You cannot be the spokesperson for two completely contradicting organisations. It’s just impossible. So he needs to make his mind up which one he wants to do.’ So I was coming from saying he’s not an evil monster, kick him out. I said, he’s got a decision to make. And so Paddy wrote back to me and said: ‘Dear Donnachadh, I’ve asked Richard and he assures me Rio Tinto Zinc is one of the best, from an environmental point of view, corporations in Europe.’

Manda: That’s either a very, very low bar or not true.

Donnachadh: I didn’t believe him. So I took that to conference and Simon Hughes was delegated me to shut me out. I said, sorry. I’ve gone through all the processes to raise this with the establishment, with the federal executive. And they’ve just decided on a communication strategy to suppress it rather than deal with it. The only thing left to me is to bring it up at conference. So I refused to be shut up by Simon Hughes, which I think actually said something about Simon’s values. That he posed as a great environmental champion, but he was the one who was sent to shut me up. And so I raised it and nothing happened. I raised it and conference shrugged its shoulders and I went home. But in the evening standard that evening, there was an article about Richard Holme saying Conference had endorsed his position.

Donnachadh: So I was absolutely livid, because there was no debate or no discussion about it. So he shouldn’t have done that because that made me really angry. So I said, okay, right; I’m going to stand for a federal executive on an anti Rio Tinto zinc platform.

Manda: Right.

Donnachadh: And what you do is you send off your election address and they put into a manifesto document, with everybody’s election addresses and they posted it out to the electorate. Which is all the conference delegates, who are elected by the members of the party. So I got a phone call around three weeks later, saying there’s a problem with your election address Donnachadh. You say we shouldn’t be associated with Rio Tinto zinc. That’s libellous. I was going ‘Pardon? What do you mean? That’s not libellous, that’s ridiculous.’ I kind of put the phone down…I just refused to remove it. So three weeks later, the manifestos all arrived through the post. I went to my page and there was a third of my page blanked out.

Manda: Censored! So the lawyers had just said, you can’t say this? Or they had decided you couldn’t say it?

Donnachadh: No, the latter. So I was horrified and shocked when I saw it first. I thought, my God, censorship in the Lib Dems of an election address. And then I howled with laughter, because I was a total unknown. Nobody had heard of Councillor Donnachadh McCarthy, but I knew there was enough decent actual Liberals, radical liberals in the party who would see the censorship. What the hell’s going on? And vote for me.

Manda: Vote for you as a point of principle. Yes.

Donnachadh: Right. So I clambered on… because we have to be fair, the one thing they do fair, in line with their principles, they do the STV (Single Transferrable Vote) elections. And so I got elected on the last count, to the federal executive, to the board of the party. And my very first meeting of the party, as you mentioned, was I felt, you know, I’d promised my electorate that I would raise the Rio Tinto Zinc issue. So at my first meeting, I had the motion down saying Richard Holme had to make his mind up. Was he spokesperson for the Lib Dem election or spokesperson for Rio Tinto Zinc? So the President, Lord… I can’t remember his name, said… So I was terrified. I was in this oak panelled room with all the party dignitaries. I’d never met an MP hardly before. And there’s all these lawyers and ladies and chief whips and leader of the party and President of this and blah, blah, blah. 32 people around a board table. And so I was kind of bit terrified. And the president party turns to me and says, ‘Donnachadh, I believe you have a motion. Do you want to propose it?’ So I said, Yes. Then Paddy interrupted and said, ‘Excuse me’, and the President said ‘Yes’. And he said, I think the federal executive (and I had never met Paddy before) He said, I think the Federal executive needs to know, if Donnachadh’s motion gets passed, I will quit as leader.

Manda: Gosh, did anyone even second it for you?

Donnachadh: No. I was very lucky that he didn’t notice that. Because he allowed me to propose the motion and have a debate without a seconder. Which actually…

Manda: Having sat at Labour meetings, that wouldn’t have gone for another microsecond. Somebody would have said no seconder, no motion, because they’re all very well trained on how to destroy difficult motions. But wow.

Donnachadh: Well I mean, I was in shock for two days. But it’s a fun story. It’s an interesting story. But really what’s at the core of it, two things. One is the power that the corporate lobbyists have and media have at the top of our political parties. And remember, the Lib Dems are the cleanest by far of the three.

Manda: Yeah, that’s the really distressing thing, isn’t it?

Donnachadh: And the second thing is the lack of practising what you preach.

Manda: Yes. If we had time, we would go into how you managed to get …

Donnachadh: One point about that, because I spent a huge amount of my time trying to get them to practise what they preach. I said, ‘If you don’t do it now, adjusting how you run yourselves, if you’re ever in government, the forces will be so huge you won’t have a hope of standing up to it.’ And sure, whatever it was, maybe sixteen years later when they got elected in the coalition, they didn’t have the guts to stand up for what they believed in. You know whether you believe or not, tuition fees is the right thing or not, the fact is that that’s what they said was their policy and they promised that they would stand up for it and they failed to do it. And I would argue, because they haven’t the moral or spiritual practise of doing what they believed in and how they run themselves.

Manda: Yes. Yes. And there’s so many big rabbit holes that we could discuss politics for a long time. But it feels to me now, that we have got a very short time frame left, that making minor tweaks to the existing political system is just not where it’s at anymore. We need a radical change to our political system and we need systemic change of the way that we work. And when you and I spoke last week, it seemed to me you had a really clear, targeted way that we could begin to do that. So let’s shift now. People have got a sense of who you are, the raw courage that you bring to what you do, the spiritual basis and the deep ideals that inform every part of your life. So with that, can you tell us what it is that’s most alive for you in this moment and where you’re taking your energy now?

Donnachadh: I feel that the most important issue in the world, obviously, right now is the climate ecological crisis. It draws everything, whether it’s social equality, human rights, you name it. This is the biggest social issue. It’s the biggest equality issue. It’s the big economic issue. It’s the biggest environmental issue. We are in desperate, dire straits scientifically, no matter what our politics is. And we don’t have time for any sector of our economic political traditions to win to solve this. It’s an all hands on deck. And that’s really challenging for people who have been political for us, doing their best to make a better world. So that’s my first position.

Donnachadh: The second thing is then, what is the structure of what we’re trying to tackle? And I would argue that strategically, the structure of the fossil fuel economy, because that’s what killing us. The fossil fuel economy is made of four pillars, and it’s made up of government, which sets the regulation for the industry. It’s the industry which produces the oil. It’s the banks who fund them. And most importantly, it’s the media who give the social and political permission for them to operate. So that’s one side of the equation.

Donnachadh: On the other side of the equation is supposedly the climate movement. And we have focussed for decades, and I’m celebrating my 30th anniversary of doing this. We have spent three decades tackling three, building three pillars. We see the movement as made up of civil society, business and government. We think that’s where we focus our action, our actions. And we looked at the media supplicants, please cover us better. We will do a little event and you will report it. And I believe that’s fatally flawed. There is a fourth pillar of the climate movement that has to be built, and that’s the media pillar. And I’m arguing that if that media pillar was on our side, rather than the other side, enabling and facilitating. The three pillars of the fossil fuel economy would collapse in 3 to 4 months. So my overwhelming message for the climate movement is very simple. Whatever you’re doing, remember, you must please, please, please include the target of creating the media pillar of the climate movement. Whatever way that means for you. Whether it’s producing your own media, whether it’s targeting the 60 top decision makers globally and the corporate media. Whether it’s creating media by local councils, whether it’s businesses doing media, whether it’s your own Facebook page. We have to get especially the corporate media on board, because if we don’t we are finished. I don’t see there’s a hope for humanity unless we actually get the corporate media on board with the urgency for the level of change needed. We saw with COVID, whatever your views on COVID, we saw when the government, people and media were united. And crucially, the media. We were able to do things nobody thought possible. Who would have thought we could stop the entire aviation industry? Who could have thought we could actually have a road safe for kids to cycle on. Who thought we could have quiet, peaceful skies? Who could have thought we could get the government to fund a what’s the word?

Manda: Universal basic income.

Donnachadh: Yeah, basically they did, for a huge amount of the population. Why? Because the three sectors of society were united. But most importantly, the media barons were supportive. That’s the lesson of lockdown.

Manda: You talked about the 60 top media operators. It sounds as if, from what you’re saying, there are 60 individuals. I’m guessing most of them are old white men, in the West, who basically are running the information structure that is maintaining the political and cultural ethos of late stage predatory capitalism.

Donnachadh: Well, that’s a different conversation. What I’m focussing tightly on is that they run the permission for the fossil fuel economy. The fossil fuel economy isn’t totally a capitalist economy. There are actually many, many different economic traditions who all have used or abused fossil fuels to run their economic systems. So I don’t want to get into that particular argument right now because I don’t feel we’ve got time to have that.

Manda: Okay, that’s fair enough. I was listening to Christiana Figueres, Outrage and Optimism podcast, and they were saying that the lobbyists who used to lobby Washington and Westminster and all the rest have moved to sub-Saharan Africa and are now lobbying for gas as the answer to Africa’s power issues. So what you’re saying, if I’m hearing, is that if we can connect with the media, we can remove the cultural permission for fossil fuel to continue to be the power underpinning of our entire culture. How do we reach these people and what do we say? Because it seems to me the few times that I engage with the media, the tabloids, the BBC, Channel Four, whatever, that there’s a narrative at the top that simply doesn’t acknowledge that climate change is a problem. You know, we’re called climate alarmists by the Steve Baker tendency. They genuinely seem not to believe it. How do we pass what we might loosely call the Breitbart narrative to actually get to a point where these guys and perhaps women will hear us.

Donnachadh: Answers on the back of a postcard!

Manda: Okay. We still have to work that one out.

Donnachadh: Well, all I can say is that they’re all people. They’re human beings. And each of them may have a story, that may be why they are where they are. I think if you look at the Desmond’s and the Barclays of this world, they have stories about why… Sometimes… People come to it in two ways. One, sometimes working class people who have made it bring angry chips on their shoulders and hate the state and hate the idea that we should help others to do what they did, because they want to protect what they’ve got. They come from a position of having nothing. They feel these billions are essential for their protection of their child within. And so they will attack the state in providing social network for other people. That’s one route they come to it. Another route they come to it, is they’ve been born with a silver spoon and they have no idea what it’s like not to have a silver spoon. They’re going well I did it, why the hell can’t you do it? So thinking about the person or where they come from, I think is important and each of them will have an individual story. And trying to find the personal connection and just go and ask.

Donnachadh: Right. I can give you one positive example of what worked. When I started having this insight, understanding, of how important the media were in terms of climate, I decided to do a vigil outside the Daily Mail’s headquarters. Something like vigil for climate change, something of that as part of the Occupy movement. And I started to do kind of like an empty chair event, where the chair of the Green Party debating with the editor of the Daily Mail and me chairing it. But obviously he wouldn’t turn up and I would make a news story out of it, just kind of an event like that. Because obviously somebody wouldn’t turn up. And then so kind of a week before I thought, Oh God, I’d better send a letter just in case! So I sent, at the last moment, I sent a registered letter to the editor of the Daily Mail. The Daily Mail has four editors, one for the Monday to Saturday, one for the Sunday and one for the Internet and one for editor in chief. So the editor of The Daily Mail from Monday to Saturday at the time, sent me an email the day before the vigil, saying Thank you for your lovely letter, and we really appreciate you kindly telling us about your 24 hour vigil. And in the spirit of that, I would like to invite you and the chair of the Green Party in to discuss our climate coverage.

Manda: Wow. Okay.

Donnachadh: So I had this extraordinary, surreal meeting where I ended up chairing the meeting between the editor of The Daily Mail and the chair of the Green Party, his head of science and her head of office. And it’s amazing conversation, but I’ll tell you one anecdote at the end of it, which is positive, hopefully we can finish up on. Is that conversation ranged widely, obviously. But I just gave an example. I said, look, you’ve been trashing the solar industry. You know, it’s an industry employs 20,000 people, it’s more than the steel industry. It’s within two or three years of standing on its own two feet. Can actually provide indigenous energy, free energy, if you like, and employ thousands of people. And I agree, it shouldn’t have long term subsidy. It needs to be wound down. But don’t kill it before it’s up and running. So he said okay, send me the evidence and I’ll see what I can do. So I went to the industry, pulled it together, translated it into layman’s language, layperson’s language, sent it off to him. And three weeks later, there’s a double page spread in the Daily Mail about how wonderful solar power was. So the message of that is sometimes go and ask.

Manda: Yeah, yeah. And I read a copy of the Daily Mail. God knows why. It just passed in front of my eyes and I wrote them a letter. One of my I’m trying to be very balanced and look, the Daily Mail could be part of the solution, not part of the problem. And they gave it a half page, which was amazing, I gather. I didn’t see it, but various people said, ‘Oh, I see you got a column in the Daily Mail!’ And I going, ‘No, I don’t think I do.’ But yeah, I think there are people in there who want to make a difference if we can get through to them. We will wind up shortly, but that editor is no longer editor. It seems to me we need to get to the owners who appoint the editors, probably more than speaking to the editors. So our task for our listeners, slightly more than we usually ask of you, is if you can find a route to get to someone who owns a major media company so that we can talk to them. Then please do let us know. And then I imagine our big task is the conversations that we have. I’m thinking quite hard about Braver Angels, who host a lot of conversations between Republicans and Democrats in the states. Not because they’re trying to change each other’s minds, but just to see each other as human. And the issue seems to be that when they’re trying to get balanced rooms, there’s quite a lot of Democrats and this may be outdated data, but the last time I was involved with this, lots of Democrats want to reach out and listen and the Republicans much less so. So they’re having real trouble getting balanced rooms. So we have to find the people who want to do this. And because we can’t just scream at them, we have to sit down and listen.

Donnachadh: I would say, remember, the Republicans are who they are now because of Murdoch and the billionaire media.

Manda: Yeah, but they’re still listening to it. You know, Breitbart is still there.

Donnachadh: If you remember John McCain, his presidential election, he had a business approach to tackling climate. But between The Wall Street Journal, The New York Post and Fox News, it became impossible for any Republican to put their head above the parapet and say, I believe in the science. We have to do something about this.

Manda: Yeah, there’s an amazing book called ‘Democracy in Chains by Nancy McLean that anyone in this field should read. One last thing I think I am remembering. Are you familiar with Scilla Elworthy and her Oxford Research Group? She was an amazing woman and she’s written ‘Pioneering the Possible’ which describes how she convened the Oxford Research Group, which sounds amazing, but actually was just a group of people in her kitchen, which happened to be in Oxford, and they were anti-nuclear campaigners and they were getting nowhere because nobody was listening to them. And what they did was they found the names of every single individual in the five nuclear countries who was involved in nuclear deliberations, found out where they lived, what their partners were called, what their kids were called, what they did, what they liked, and began writing them personal letters. They also published all of these data which were then banned by the government as being basically you can’t put this out in the public domain, but they wrote to them such that when they met them in person, they were able to have personal conversations and that by then they knew as much about the nuclear industry, the Oxford Research Group, as the people involved. And in the end she was able to convene a meeting of everybody in one of the beautiful old Oxford colleges. And she tells this wonderful story of an American general. And she’s in the room and he comes in andhe’s talking about the atmosphere and how amazing it is. And she goes, ‘Well, yes, you know, 12th century building’. He’s going, ‘No, no, no. It’s more than that, there’s a sense in the air.’

Manda: And she said, ‘Well, that will be the people meditating in the room below’. And she watched the curtain come down because the idea that someone was meditating was way too much for this guy. And then she said, ‘Do you remember the old man with the silver hair who served his soup at dinner last night?’ And he’s like, ‘Yes’. And she goes, ‘Well, he’s just in the library and he’s just, you know, trying to hold a good intention. And that’s what you’re feeling in the air.’ And because she was able to make it personal and he had met this old guy and he wasn’t obviously some complete freak that the word meditation had triggered in the general. He calm down and stayed in the room because she said when she watched his face, she thought, that’s it, he’s going to leave. And if the Americans leave, we may as well not be here. But he stayed and they got their nuclear non-proliferation treaty. But it took them a decade and I don’t think we have a decade. So we need a lot of us to be doing the work together at every level. I think you set an intention to be on the stage at Covent Garden and leaving aside the swan dive that wasn’t caught, you got there. And so I think we need the people who can set clear intent to set a clear intent that you and I and anybody else involved is coming away from the meeting with the people who really matter, feeling that we’ve made a real heart connection with these people and we’ve given them a vision of how they can be part of the solution.

Donnachadh: That’s a beautiful, beautiful summing up. But if I can add one more layer to it.

Manda: Go for it.

Donnachadh: The intention is, yes, I’ve been working up the intention of assembling a global meeting of the world’s corporate leaders, to have a presentation made to them on the climate, to have an appeal from the heart and the soul for them that we need them. We need them on board. Whatever our politics, we need them because the planet is on fire and without their help, it’s gone. So that’s my intention that such a meeting should happen. But the real intent is that the global media, the corporations are the fourth pillar of the environmental movement.

Manda: Okay, or that they become the first pillar of the environmental movement?

Donnachadh: They’ll become an essential part of the fourth pillar. It’s not just them, but they will be totally on board with saving humanity, those 60 people. That’s the intention.

Manda: Okay. All right, people, you have your mission. Go out and make it happen in whatever way you do your meditations. This is our new intent. That’s beautifully stated. And Donnachadh, thank you for your courage and vision and idealism and everything that you bring to this. It’s been an absolute pleasure to speak with you.

Donnachadh: Bless you.

Manda: And that’s it for another week. Huge thanks to Donnachadh for everything that he is and says and does. Once in a while, these conversations feel as if there’s something else moving through us. And this was definitely one of those. It seems to me that Donnachadh’s clarity of intent, his ability to formulate a clear, simple, straightforward and immensely powerful intent and then hold it, is one of the most powerful ideas I have heard in a long time. And definitely something that we can all get behind. Because the more that I do the shamanic work or Accidental Gods or simply sit up the hill, the more that I understand that clarity of intent, that capacity to set and hold something clean and clear at a heart level, with our heart minds. Fully with our heart minds, almost to the exclusion of everything else, is the single most powerful thing that any human being can do. And we can do this. I think there are ancillaries I set up Thruopia because I believe that we need the narratives of what the future looks like if we get it right and how we might get there. We need those roadmaps. And they may be a part of helping the 60 most powerful people on the planet to understand that there is a future in which they can play an active role and feel, at worst, as fulfilled as they feel with what they’re doing at the moment. But at best, they could feel considerably more so.

Manda: They could become part of something that is genuinely generative and heartfelt and that touches them at levels that they have not yet reached. This is possible, but the clarity of the intent that we need to set is simply that they become the fourth pillar of the climate movement with everything that that entails already wrapped in. We don’t need to define how, we just need to define the outcome. This is the nature of setting intent. It occurs to me that we speak about this a lot in the shamanic workshops and a bit in Accidental Gods and quite rarely on the podcast. And if there is an appetite for me to do a bonus extra podcast, simply talking about the nature of intent and how we set it and how it works, then I will do that. But you need to tell me. So find me on social media or manda@accidentalgods.life and let me know what you think. And if there is enough, then I will do it. And beyond that, we will be back next week with another conversation.

You may also like these recent podcasts

What do we really think about Food? Revolutionising what we eat with Sue Pritchard of the Food, Farming and Countryside Commission

This conversation was sparked by the FFCC’s inspiring Food Conversation – which brings together ordinary people and begins to unpick the web of deceit surrounding our food – and replaces it with something that is real and decent and nourishing on a physical and systemic level.

How do we live, when under the surface of everything is an ocean of tears? With Douglas Rushkoff of Team Human

Douglas Rushkoff shares with us the palpable “ocean of tears” lurking beneath the surface of our collective consciousness—a reservoir of compassion waiting to be acknowledged and embraced. His candid reflections on the human condition, amidst the cacophony of a world in crisis, remind us of the importance of bearing witness to the pains and joys that surround us. He challenges us to consider the role of technology and AI not as tools for capitalist exploitation but as potential pathways to a more humane and interconnected existence.

Evolving Education: Building a Doughnut School with Jenny Grettve of When!When!

Jenny Grettve’s heart-mind is huge and deep and we explored many areas of the transformation that’s coming, from the evolution of a primary school along Doughnut Economic lines to the future of architecture, to the role of systems thinking in our political, social and, in the end, human, evolution. It was a truly heart-warming conversation and I hope it helps you, too, to think to the edges of yourself.

Building Trust, One Conversation at at Time: Cooperation Hull with Gully Bujak

This podcast exists to open doors, to let the world know some of the many, many things that are happening around the world to bring us closer towards that just, equitable and regenerative future we’d be proud to leave behind. And this week’s guest is someone who lives, works and acts at the cutting edge of possibility.

STAY IN TOUCH

For a regular supply of ideas about humanity's next evolutionary step, insights into the thinking behind some of the podcasts, early updates on the guests we'll be having on the show - AND a free Water visualisation that will guide you through a deep immersion in water connection...sign up here.

(NB: This is a free newsletter - it's not joining up to the Membership! That's a nice, subtle pink button on the 'Join Us' page...)