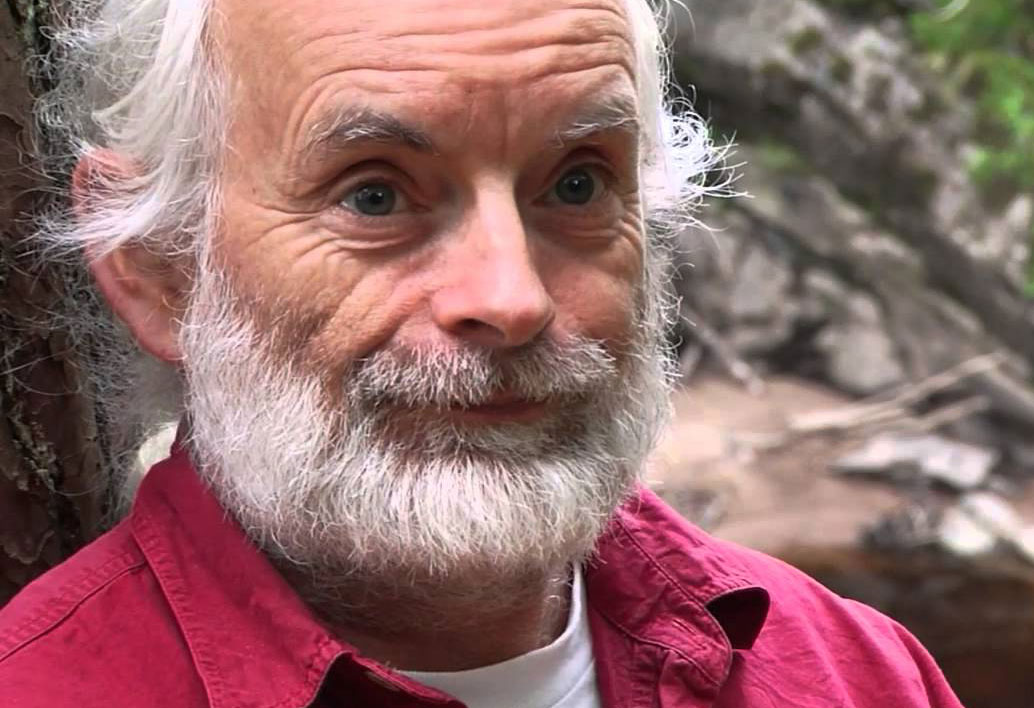

Episode #67 ReWilding the Forests of Life: Alan Watson Featherstone, Trees for Life and moving forward

How does it feel to commit – completely, without reservation – to the flow of life? Where do we find the courage and resilience to take the first steps on the path? And how does the world – that same flow of life – support us when we have done so?

In this second of two parts with Alan Watson Featherstone we explore more deeply the creation of Trees for Life – how it arose and what it entailed… In itself, this is impressive, but what makes it inspiring for those of us who might not be able to set up a world-changing forest reWilding project, is the extent to which, having made a commitment to change the world, the world itself supports us in our endeavour.

This is what is so inspiring about Alan’s story, what gives us hope in a world hurtling towards so many tipping points: that if we listen to our innermost yearnings, if we follow our hearts and let our intuition lead us – then when we step onto the path of our calling the world supports us in our endeavour.

Episode #67

LINKS

Alan’s website

Trees for Life

Findhorn community

Auroville community

Restore the Earth

Global Ecovillage Network

Dreaming Your Soul’s Path Gathering at Accidental Gods

In Conversation

Manda: This week, we’re back with the second part of the conversation with Alan Watson Featherstone. If you haven’t heard the first part, then I do encourage you to go back and download last week’s conversation. This one will stand alone, but it will make more sense if it’s linked up to the first part. So for the rest of you, you already know that Alan is an ecologist, a nature photographer, an inspirational speaker and founder of the astonishing charity Trees for Life. So without any more interruption, people of the podcast, please welcome Alan Watson Featherstone.

So, Alan, welcome back to Part two of our two part podcast. When we left, you were just about to head off to Auroville. So let’s pick up the story from there.

Alan: Thanks, Manda. Good to be back here again. And yes, in 1985 I went to the community of Auroville in India, or t was in some ways a sister community to Findhorn. It was founded as an intentional spiritual community with the purpose of being a living laboratory for human evolution. And the woman who founded it, an elderly French woman called The Mother, had a vision of a centre where people from all countries would come together behind a common cause of human unity, and to help humans take the next step in our own evolution as a species. So I went there because I heard that they were doing a lot of work of reforestation. And Auroville was founded in a desertified area of land in the South Indian state of Tamil Nadu, where the earth is brick hard for 10 months of the year when there’s no rain, and then they have monsoon for two months. And that rain, in the absence of vegetation, which had all been deforested, had taken away all the topsoil. So we had this brick hard earth and gouged out were these canyons where all the water had flowed away. So the people had planted two million trees. By the time I got there, they’d put little mounds around the contours of their fields to catch the monsoon rain and the trees they planted and provided a bit of shelter and shade. Birds had come and brought in seeds and the whole process of healing the earth was well advanced. And because it’s the tropics, things grow quickly. I walked there in a forest that was two years old and the trees were 15 feet tall, five metres tall, and birds were coming back and all the life was there.

And it was like this miracle to see. And I thought, my goodness, if they can do this in India, one of the poorest countries with no rain for 10 months of the year, no soil, we can do this in Scotland. Because I already felt this calling to help the forest in Scotland. And in Scotland, we’ve got plenty of rain. We’ve still got some soil, you know, so we are at a much better starting point. So that was a real breakthrough and revelation for me. And what it did was after having worked in the educational programmes of the foundation at Findhorn, reconnecting deeply with nature, this is where my heart really is. This is what I need to make the centre of my life. The education work is really good, but it’s not what I really want to be doing. So after that time, and I will come back to Findhorn, and I moved out of education, although I ended up organising a big conference with some other people. But I was the main organiser on The State of the Environment in 1986, and that was the year of the Chernobyl nuclear accident. So the environment was really up in public awareness.

And the event, it wasn’t really a conference. We called it a gathering. We only had five speakers during the week, and it was designed to do what Findhorn does best, which is offer a transformative experience. So we had five speakers inspiring people. But the centrepiece of the week was what we call Transformation Day on the middle day, the Wednesday. And there were no speeches that day. Instead, they were in day long workshops, things like fire walking, sweat lodge, native Aboriginal Australians’ traditional rituals, despair and empowerment work, and a deep workshop on healing the male and female divide. And people had a choice to do one of those. And the idea was that it would help make them a personal shift. On the final day of the conference, the event was called One Hour, The Call to Action. I think many people felt that on the final session that was going to be the blueprint, the call to action. You know, this is what we want everybody to tell governments to do. In fact, the final session was an open space in which we invited anybody who felt moved to stand up in front of the three hundred participants, and make a personal commitment to do something positive for the planet as a result of their experience that week.

Some people, some people got up and said, I’m going to dig up my lawn and grow organic vegetables for myself. I’m going to not use plastic. When it came my turn, and it was voluntary and people didn’t have to do it, some people did, some didn’t. But when I felt moved to speak, I stood up and said I commit myself to launch a project to restore the Caledonian forest in the highlands of Scotland. I’d been going out there 1979. I’d seen Glen Affric, which reminded me of Canada. It was like I never knew there was a bit of Canada in Scotland, with old trees covered in moss and lichens and tumbling waterfalls and water lochs and rivers and mountains. And, you know, it was a far cry from what I knew of. Most of Scotland is bare, treeless landscapes. But I’d also seen the old forest was dying, the trees were all old and they were dying of old age and not being replaced by any humans, except in one place where a visionary man had put up a fence in the 1960s to keep deer out, to stop them eating the baby trees, and the forest would come right back. And I just listened and kept thinking, well, why are they not fencing off the other areas there? Why is nobody doing this? The rest of the forest is just dying off. Why is the Forestry Commission not doing it? They own the land. Why is the government conservation agency… that’s their job, to protect nature. Why are they not doing anything about this? And when I saw these old trees and these overbrowsed seedlings. There were lots of seedlings and they were just getting chewed down to nothing and dying, and I felt this land was calling out for help, I felt… there was no message. But the feeling I got was, you know, Help! We’re dying off. We can’t do anything. We need somebody to help.

So I felt this for a while, and it slowly began to dawn on me that I saw the problem. And again, paying attention to the messages, to the feedback that the universe provides that I talked about in the first part of this podcast, you know, it was like, it began to dawn on me. Well, I see the problem, I feel the pain of this land. Maybe I need to do something about it. So in this conference in 1986, I stood there in front of three hundred people and said, I’m going to launch this project to restore this forest. And it was a really audacious thing to do at the time because I had no training in forestry or ecology. My university degree, which was meaningless by that time was in electronics. I had no skill to do it. I had no access to land, I had no resources to put into it. On a practical level, I had nothing to fulfil this huge commitment I had made. But I had the most important things. I didn’t realise at the time, but I had the most important things, which was I had a deep alignment with my heart and a growing connexion with the Land. Through my time in the garden at Findhorn, I had really come to see that I’m not separate from nature. I’m an integral part of nature. And when I acknowledge that, I can then see not only do I give something to nature, but nature gives something to me. I get something from nature and it has to become a two way process. Our normal relationship with nature in the world today, it’s very much one way. It’s take, take, take. I’d begun to learn to give back, to give back my love, to give back my care. So I had this alignment with nature. I had this alignment with myself, and my calling of I need to do something to make a positive difference in the world. And I had enough experience from being at Findhorn for eight years by then to know that if I followed that calling, and acted in trust and faith, all that I need to fulfil my purpose would come to me.

Manda: Gosh. But still, it takes huge courage. And I do want to just take a brief break and say, yes, you’ve had eight years at Findhorn. Yes, you’d had the experiences that demonstrated to you that help is there once we make the commitments that we make. But it still sounds, you know, compared to digging up the lawn and growing vegetables or stopping using plastic, both of which are entirely laudable, you had just committed yourself, and and we know enough about you now to know that when you’ve made a commitment, that means you’re going to give it everything, to completely changing your life, I think, from the sound of things. Changing the focus, changing what you were doing, changing how you were doing it.

Alan: Well, I didn’t see it at that time. I saw it as a next step, And it it unfolded gradually. So after that, some people came up afterwards and said, that’s great. You know, really inspired by what you said, how can I help? And some people did have a specific way. Somebody gave me five pounds. You know, somebody else said, I’ve got a friend who publishes an alternative magazine. You know, if you write an article, I can get them to publish it for you. Some people invited me to go and give talks. It started very small and that was in 1986. I began going out more consciously with that intention in mind. I thought, I’ve got to train myself. I’ve got to understand, as far as.. so began going out there, I’ve started going out with people who knew the forest to learn from the man who fenced off the area in Glen Affric in the sixties. I made several trips out with him to pick his brains, and get the benefit of his experience. And I began to absorb and absorb, and make contacts. But it took three years before any practical action could happen because I had to learn for myself what to do. I had to make contacts. I had to raise money. And it was another year, almost another year before any significant work took place.

And in 1990 I’d raised enough money to pay for a fence and I’d found a partner in the Forestry Commission, quite surprisingly, they owned as good remnant in Glen Affric. But their budget had been cut in the years of the Thatcher government and they were being pushed to generate more profit, and their conservation budget had been slashed. So the man in charge of that area at the time was a relatively young man. And I think he must have gone out on a limb because here I was, this long haired, bearded, alternative looking character living in an intentional spiritual community with no experience in forestry, wanting to engage in a partnership with the Forestry Commission, the professional government agency. And he said, yes! It was a miracle.

Manda: Did you ever get a chance to talk to him about why? What was going on for him? Was he their secret Greenpeace person in the way that you had been in Canada, do you think? Was he already up for it?

Alan: No, I don’t know exactly. I never had that conversation with him. He left a couple of years later. He was actually one of these Christian special denominations. He became sort of involved with them. He went to the Comoro Islands, partly in a missionary type role. So he had his own spiritual path.

Manda: Interesting. Anyway. He said yes. And?

Alan: He said yes. And we put up this fence in 1990. At the time, the Findhorn community had a very good PR lady and she was very keen to promote this, to raise the profile of Findhorn. And she’d been a professional PR person before she came here. She said this is a great opportunity to get some media coverage. So we found out that David Bellamy, who then was kind of the equivalent today of Chris Packham, or somebody like that, or even David Attenborough, you know, he was all over the media. He was the big media star. He was coming to Inverness to give a lecture, and we managed to get in touch with him and said, could you come and close the gate on this 50 hectare, one hundred twenty five acre area to keep deer out, so the Caledonian forest can regenerate? And he said, well, I’ve got a two hour gap in my schedule. If you can get me on site and off again, I’m very happy to support you. Now the only way we could do that was hire a helicopter. Oh my god, a helicopter, not ecological, expensive and we don’t really.. the PR lady talked me in to it. She said, Alan, this is your chance. You’ve got to go for it. Because we got the helicopter, we got David Bellamy, we got the two national television channels in Scotland at the time to come and cover it. BBC Scotland interviewed me and we got a big feature in The Guardian. and that was the starting off point, because till then it been me with a few volunteers helping. And I was only, I had a different job in the community at the time. I was doing this in my spare time. Basically, up till then it was it was an idea. And then suddenly it became incarnated in reality.

Manda: Yeah. And then life changes.

Alan: Spirit came into physical form on earth in the Caledonian forest. The fence was up and it got this huge media coverage. And that was a key point. And this is one of the crucial things about my journey. It’s great to have ideas. It’s great to have inspirational spirit. But until it actually gets embodied in form, it remains there. And as soon as it comes in form, it becomes magnetic and attractive, and it will attract interest and support. That was the key point for Trees for Life. That was the transformational, that was the pivot point. We then went on in the next two years to do two more fences for the Forestry Commission. Then we started working with the National Trust for Scotland, private landowners, and it grew from there, because people by then were seeing the benefit, and understanding what it was that we were trying to do. We could take them and show them. Inside the fence, young trees growing; outside, the overgrazed seedlings dying. It was black and white, it’s so obvious. So the power of positive example, the power of a demonstration.

It’s like ideas, spiritual impulses, are like seeds. And if you’ve got a seed in a packet on your shelf, it’s a seed. And it remains a seed until it’s put in the soil. So if you take a spiritual idea, you take an impulse and inspiration, you can have it there, and it will stay there. But when you actually put it into physical form and you start to feed it with your energy, it takes root and it grows. And the idea of Trees for Life, it took four years, almost four years to take root. But I was impatient in those early days. I wanted it to happen now. And I had to learn patience. But that time was actually the project, the idea taking root, putting its roots down. And a tree, when a tree seed germinates, the first growth is not something coming up above ground. It’s the root tendrils going down. So that was the first visible sign, was the significant visible sign, was this fence going up. Then people can see it and it’s visible. It’s manifest. And if you keep feeding it, it starts the snowball process of drawing in what it needs to grow and develop, because ideas, projects, spiritual impulses have a life of their own. They have a spirit. They have a potential. And the job of someone like me is to be the midwife, to give that potential the best opportunity to grow, just like a midwife’s job is to help a child come into existence from the mother’s womb as gracefully and peacefully and non problematic as possible so that the child can then fulfil its potential that its life offers.

Manda: Most midwives bring the child into existence and then move on to another one. You stayed with Trees for Life for a long time. Tell us about how that impacted your sense of who you were in the world.

Alan: Well, that’s a good question. Thanks. I think the immediate answer that comes to mind is, the thing I say to people is that when I tap into my heart, to my spirit, to my purpose, to my deeper calling, there are no limits to what I can achieve. There are no external limits. The only limits are those voices that are inside me, that I haven’t cast off from my upbringing. What would my parents think? I’m not good enough. I don’t have enough money or resources or training or skill or whatever, those are all the things that hold many people back, I think. And my journey of self discovery, of discovering my personal power is that it is unlimited because that personal power is the essential underlying essence of the universe. Spirit, All That Is, call it what you like, the ocean of being from which we all spring and we all have access to that, and the access, the key to it is listening to our hearts. And then the second step, hearing the message of our heart and then it’s opening the heart as fully as possible to allow as much of that to come through.

So when I started Trees for Life, I started with nothing, I had nothing on a physical level. But I had this inner alignment. So it then became a question of how open and willing am I able to go. So Trees for Life grew, and we began engaging volunteers very early on. It was all volunteers initially, including myself. And we then started running these weeklong volunteer projects, which I was able to use my experience from Findhorn education programmes. I translated that into working in the forest, and whereas at Findhorn they do lots of group activities like circle dancing and that type of thing to form the group, at Trees for Life, we planted trees together. We lived in one bothy together. We cooked together, and the bonding happened. And then people planted trees, and they surveyed, and they took down old fences, and they worked together in all the elements. I remember some days people getting blown over by the wind, it was so strong. Horizontal snow. Saying, we’ll take off, we can stop now. We can go back. No no, we want to continue. And that’s that’s the most memorable thing, because they were doing something outwith their ordinary experience. They were serving a bigger vision. So through all this, people got touched. We started a training programme to train people to lead the weeks, and some of them went on to set up their own projects, and it began to to grow and snowball.

Manda: Can I just ask a purely logistical question of, you said in the beginning you fenced it so that the deer would stop eating the seedlings. So there’s a degree of regeneration happening anyway. When you come to planting, what were you planting? You weren’t planting, obviously, serried rows of forestry monoculture. You were planting something diverse. How did you decide what to bring in and why was that?

Alan: Well, planting was not the first step. The first step was natural regeneration, as this is all about Findhorn principle, cooperation with nature, cooperation with nature. What does nature want to do? Well, if nature was left to her own devices, the highlands would be largely forest, not everywhere, but most places. That’s what happened ten thousand years ago, because in the previous Ice Age, the whole country was covered by ice. And when the temperature warmed up, there was no Forestry Commission or Trees for Life or anybody to plant trees. They came back by themselves. Seeds were blown by the wind, or carried by birds. And that’s exactly what would happen. Now in much of Scotland today, if we took the deer and sheep away, that would happen in some places where there’s a seed source, but in many parts there’s no nearby seed source. The nearest living tree might be miles away, so reforestation would be slow to occur. So we started with regeneration around the existing remnants, because one of the principles of what does nature want to do? Bring back the forest, OK, where is the forest? We can, that’s the easiest place to start because there was already the foundation for it there, and the fungi are there and all the other species, the insects are all there waiting to expand.

So start regeneration. So planting only started a year or two later, and we plant native trees, and we try to match them to the right soil conditions. So it’s about power of observation. Pines like to grow on dry, sandy and well drained soil. So we look for those sites to plant pines. Wetter areas, you can put species like alder or willow. So it’s the native species, and looking for the right conditions. So it’s building up this relationship with the land.

Manda: And had you got more land by then, or the Forestry Commission were giving you land?

Alan: We were working on other peoples’ with the Forestry Commission, the National Trust for Scotland, private land. But it had always been my goal to buy land. And I tried to buy land in the early 1990s. Three different areas came up in Glen Affric, each time they sold quickly. The third piece I managed to raise all the money to meet the asking price, only to be outbid by a Dutch businessman. And that was a huge blow, in 1995. So years went by. The charity grew, still wanted to buy land and in 2004 I received an email and it was one of those emails, I thought it was a scam. And those days, I don’t know if you remember them. You used to get these emails from sort of Joan Ogongo of Nigeria saying, you know, I have an elderly uncle who has died and he left me five million dollars in his will. But I need five thousand dollars to pay the legal fees. If you come in as a partner, I’ll share the money with you. It was in that time, and I almost didn’t reply to it because it wasn’t a personal name. It was signed, two initials and then a last name. And the email said, I’m dying of cancer. I’ve got money I want to buy land in Scotland for forest restoration. Are you interested? Well, I almost didn’t reply, but it turned out to be genuine. And it was an English woman, but she was living in Colorado and she had terminal cancer. And she had found the Trees for Life website, because I’d taken a lot of effort with my colleagues to build a good website to communicate the vision, because that’s always been a part of Trees for Life. It’s not just to restore the forest, but to inspire people elsewhere, because restoration and what’s called rewilding now, but recovery of natural ecosystems has to happen everywhere, not just this one. So we’ve got a good website, so she found this website, said this charity meets my objectives. So I started engaging with her. I never met her, because she was in hospital and she couldn’t receive visitors. I talked with her on the phone, email exchange, and we developed a bit of a relationship and she said, yes, I can give you this money, but the condition is you’ve got to raise the rest of the money before I’ll give you any.

Then I was in a meeting with the Forestry Commission and somebody on the neighbouring estate to Glen Affric. And we were looking at, we’d done a bit of work on private land and the Forestry Commission land, and we were trying to negotiate doing some work to restore what was a forestry plantation into a bit of native woodland. And I said, wouldn’t it be great to send it over to this other bit? And that one of the people in the meeting said, oh, yes, and you could actually maybe talk to that other landowner. He’s just died and the estate might be put up for sale. So my ears immediately went out there. So this is the universe giving feedback. So I started following this up and found out this land was up for sale. The man had died without leaving a will, an Italian man, so pursued it. We managed to negotiate a purchase price, £1.65 million. And this woman in the states, she ended up giving us £900,000. We had to raise the rest of the money, which we managed to do. So Trees for Life took ownership of ten thousand acres of land in 2008. So this is what I was talking earlier about. The power potentially is unlimited. I started Trees for Life with nothing and here somebody was inspired to give us £900,000. A charitable trust gave us £365,000 and two individuals who we had no idea, they were just people in our database, they gave us £100,000 each. So put out a clear vision, sound a positive note. And if you’ve got a track record that people can see, and see that it’s worthwhile, they will respond. The universe responds to positivity.

Manda: Yeah, it is worth following your heart’s path.

Alan: Yeah. That that was a turning point for Trees for Life, because up till then we’d been working in partnership with other landowners, which is good. And it’s good to have partnerships. But we were always necessarily constrained. You know, partnerships with other organisations, they have different objectives. Now the Forestry Commission’s main objective is to grow timber. And yes, want to conserve forests and native forests where they can, but primarily involved with growing timber. And because they’re a government body, they’re not allowed to be radical. And we would talk about we want wolves back, and the Forestry Commission can’t make a statement like that! But we were always having to compromise. So having our own land meant we could really put our vision into practise, without the constraints of having to meet somebody else’s agenda. And that, of course, was another key point. Of course, it transformed the organisation too, because instead of just being a charity we were now a landowner. As a charity, we had no voice in deer management, for example, because that is the realm of landowners. Suddenly we had a voice in deer management, and we could actually speak, and we had to be viewed as an equal landowner, not just as a charity that was coming at landowners with a different agenda. So it was a transformative experience. So the charity grew. By the time I left, it was, had a turnover of over a million pounds a year and a staff of I think twenty or twenty one people. Remember, that started from nothing.

Manda: Yeah. From you standing up in front of three hundred people and making a commitment.

Alan: And the charity is still going now. It’s still growing, it’s got more staff, it’s engaged in a lot of other aspects of rewilding now, and it’s one of the key members of the Scottish Rewilding Alliance. And yeah, there’s lots of good things going on there.

Manda: It seems to me, as as a former scot, or an expatriate scot living in England, that the Scottish government gets things like this in ways that the current English administration doesn’t. Is that fair? Is the government supportive of rewilding, of restoring the forests, of bringing about wolves, things like that? Or are you constantly fighting against a bureaucracy that doesn’t get it?

Alan: Well, the truth is somewhere in between. I think we are a little bit further, better developed in Scotland, but we’re still a long way from the government getting rewilding. The government has tree planting targets to address climate change. But most of that, the thinking is still, we need more timber plantations, we need more forests that are there for human use. They do have support schemes, there are good grant schemes. Trees for Life has used them, other organisations use them for tree planting. But they’re all still based on forestry principles. So they’ve got tree density figures that come from a forestry background, a commercial forestry background. At Trees for Life, for example, we were saying it’s not just the trees that grow well in the valley bottoms. We need to talk about the mountain scrub, that grows at the tree line. So there’s been a huge campaign, that Trees of Life has been involved in, and other organisations, to try and get funding for that. And there’s tiny, tiny little bits of funding for it. But that’s a crucial area. That’s the edge. Ecologically, edges are the most important zones where one ecosystem meets another. That’s where you get your richness. So, yes, it’s taken some steps in the right direction, but it’s still a long way from being a government that fully is based on ecological principles. It’s still driven as all governments are by economic principles first. And ecology is a nice add on, and we’ll do it where we can and we can do a bit more. But the radical transformation that is totally that is required. You talked about wolves. Well, as you may know, Scotland has had a beaver reintroduction project from 2009 to 2014. I went on a beaver study tour to Brittany in 1996 to look at a beaver reintroduction site there, because I’ve always advocated the return of the species. So beavers were finally accepted as a native species in Scotland after the trial ended. But the government has said, they’ve stamped down completely on unofficial beaver reintroductions. And they’re not allowing further translocations of beavers in Scotland at the moment because of pressure from landowners. In Tayside, where beavers arrived of their own accord, nothing to do with Trees for Life, but the beavers got into the Tay. It’s not the official trial, and they’ve expanded. And there’s been some problems with farmers, with some of their fields getting flooded.

And I can have empathy with farmers, but they’ve kicked up a big fuss, put pressure on the Scottish government. And the Scottish government said because of these issues, we’re not going to allow beavers anywhere else. They can get their under their own accord. But they’re not, we’re not going to allow translocations. So beavers will be getting shot. Although it’s an officially protected species, 87 were shot in a period of six months. And it’s supposed to be the last resort, but in fact, they’re giving these licences out. So Trees for Life is actually taking the Scottish Conservation Agency to court as we speak, to challenge them on this, because shooting beavers should be a last resort. There’s lots of landowners and areas of Scotland would like beavers, would benefit from beavers. It’s being blocked. Crazy. So that shows how much work still to be done. We’ve got a long way to go.

Manda: Yes. And a long way of educating people that the work that beavers do in the end is beneficial to the totality of the environment. And the fact that a field may flood once or twice is not necessarily a catastrophe. And it is clearly if you’ve got your wheat crop or something on it. All right. That’s a whole different conversation. Let’s not get lost on that rabbit hole. It’s too distressing. So let’s come back to you and Trees for Life. And you said that you had left three and a half years ago. So where are you now? And where has the learning of Trees for Life taken you? Because I’m guessing that it was such a core part of your life for such a long time that, again, a lot of courage and a lot of resilience is needed to reinvent yourself into a new Alan Watson Featherstone. Where are you now?

Alan: Well, thanks, that’s that’s a great question. I’m still on my journey, and I want to take that journey back to that point I mentioned in the first part of this podcast, where I talked about my sort of mini enlightenment experience of knowing there was a purpose to life, but not knowing what it was. So over the years at Findhorn and as I was working with Trees for Life, my life purpose became clear to me. And that life purpose is two aspects. One is a personal aspect. And the personal aspect is that I need to explore, discover, learn who I truly and who is my true self. Not the little self, not the ego, not the personality, but the spiritual self. My core. And I need to embody that and allow that inner part of me to express in the world. I need to be visible. I need to be seen for who I am, not for what I do, not just for trees, for life, for the house I live in or the community I live in, or the friends I have or anything like that or my life values. But who am I? Who is the spark? This fragment of All That Is, this aspect of the divine, of the ocean, vast ocean of being that has come alive in the late 20th century, early 21st century in this particular body. How do I express that inner connexion with All That Is, with spirit? So that’s one aspect of my life purpose. That’s the personal aspect.

And then there is what I call the transpersonal, which is a thing of service, this altruistic part that I have been aware of since I was a teenager at least. And for me, that has clarified that that is specific to helping to heal and transform the relationship between humans and the rest of nature. And that has taken different forms over the years. So it took the form of working in the vegetable garden at Cluny for a while, it took the form of setting up the recycling project. It took the form of Trees for Life. It now takes the form of my own vegetable garden, and it has had an expression for a while and something I initiated in the late 90s and worked as part of Trees for Life called Restoring the Earth, which was a hugely ambitious project to have the twenty first century declared the century of restoring the Earth and that the purpose that unites all humanity. We’ve never had a purpose that unites all humanity. For that purpose would become helping the Earth recover, helping the Earth to heal, and it needs to be at least a century long. But it would take the example of Trees for Life and other similar projects to say we need to do this all over the planet. We need as a human species to give back, to help the Earth, to heal. The Earth is like our own human bodies. It’s alive, and it has an inherent ability to heal its own wounds. But we prevent that just as we were preventing the restoration and recovery of the forests of Scotland by having too many herbivores, deer and sheep. So we prevent it by our impact on ecosystems, overfishing, cutting down forests, pollution, plastic, all the things that we all know about the impair the Earth’s ability to recover from that overexploitation and damage that we’ve inflicted. So my vision was to facilitate that becoming the first shared goal of all nations, all cultures, all countries. We’ve never had that before. It’s every day for itself. It’s still endless economic growth. And we all know that it’s got no future. We need to come up with something new. And surely the first task for us with a higher and more enlightened Conscious has to be OK, we’ve inherited this wounded, depleted planet that’s on the edge of a sixth mass extinction and is in the brink of climate breakdown. We need to take stock and do what we can to help heal those wounds, to help the Earth get back into balance, vitality, diversity again.

So that is part of my work of helping to transform the human relationship with nature. So nowadays, I do quite a bit of public speaking. I do writing. And at the moment I’m in the early stages of exploring a potential restoration project for temperate rainforest on the west coast of Scotland. Not many people know that Scotland still has tiny pockets of rainforest like Ireland, like Wales, like even England. Down in the Lake District and in Devon and Cornwall, rainforest covered the west coast of these islands, almost completely vanished. So now there’s interest in restoring those. And there’s a potential project, very early stages, but very exciting because it’s again, there’s lots of synchronicities around it. Spirit and the universe is calling me. So I’m just starting to see that. And I don’t know where I’m going. I’m working on a couple of book projects, one about the endangered monkey puzzle tree forest of Chile. Many people know the monkey puzzle tree as a specimen in gardens and town parks and botanical gardens here. Very few people know it comes from the Andes of southern Chile and Argentina, where it’s highly endangered. I first went there during one of my trips to South America in the 1970s and I felt called to go there in 2015. I spent two weeks in the forest and it’s suffering from deforestation, from climate change, heading the same way as so many forests around the world. I’m not going to go and live in Chile. I’m not going to start a project to restore it there. But I thought, I can do a book about this. So I’ve made four, five trips there over a period of three years done a lot of high quality photography. I’m looking for a book publisher at the moment. The book is almost complete. I’ve got a number of other projects at various stages of ideas or early development. So it’s finding new ways to get the message out. I feel like I’m on the same path. I’m still being called. And most of these things come to me. I have a website, so people find me. You found me. I didn’t reach out to you and say Manda, could you do, could I do a podcast with you? You came to me, and this is what happens. People are coming to me. I’ve been asked to give a talk to Natural England staff later this month about rewilding and they’re looking at woodlands, and how can they do things. And we know that the British government has made a recent commitment to have 30 percent of Britain officially protected by 2030. So what is officially protected? Most of our national parks at the moment are protected. They protect the destruction of nature. No burn, grouse shooting, overgrazing. You know, we’ve got a huge turnaround need there to actually make them really protected, to have nature protected. So there’s an opportunity for me to feed into Natural England. So I’m responding to these things, and I don’t have a five year plan, and goals of what I set out to accomplish. But I’m following my intuition and responding to the feedback from the universe and seeing where that takes me.

Manda: And how does that fit into the first part of your two part purpose, the personal exploration to discover the core of who you really are? Because that is one of those things that feels to me such an astonishing and beautiful and courageous insight even that it needs to happen, and that you’re able to link it then with your transpersonal concept of helping the whole of the world. But in terms of where you are at this moment, on the ninth day of a fast that may last two weeks, and bouncing from the sound of things, lots of different calls on your time and on your energy, how does that help you move closer to who you really are?

Alan: Well that’s a great question, and I define those two purposes quite clearly as discrete things, but actually they’re not separate. Finding out who I am means listening to my heart, and listening to my heart is what has led me to do things for nature. It ‘s led to Trees for Life, it’s led me to do the things I’m involved with now. And it’s the act of doing those things then that draws out of me something that has not been manifest before. So for example, I said earlier when I went to Findhorn, this was in the first part, when I went to Findhorn and people said, OK, we’re going to introduce ourselves. I was ready to run out the door because I hated speaking, the though of speaking in groups. Now, I mean, I have a real talent, and I’m not boasting here. I have a talent to speak and communicate to people, because I can share my vision in a way that touches me. Two days ago, my TEDX talk on restoring the Caledonian forest reached the milestone of half a million views and I said, Wow, that’s me. I’ve touched and reached half a million people. That’s just a little Alan here. In the north of Scotland. So the two feed into each other. So by saying yes to my big visions, I’ve never done those things before, I have to become a bigger person. I have to grow. And I do occasional workshops, but I don’t do many workshops, and I see people sometimes who spend all their time doing this workshop, that workshop, and they’re will good workshops. Life is my workshop. And by saying yes to my heart, and staying true to that, and facing up to the challenges and obstacles, because they always come, facing up to those and finding the way through, around or beyond them, is my cutting edge. That’s my learning experience. That’s where I grow. And that’s where I discover more of who I am. So the two things are intimately interwoven and interdependent. And every time I take a step forward, if I make some new understanding about myself, I can apply it. And every time I make a new commitment or take a step with something else, I’m forced to do something I’ve never done before, which draws something else out of me.

Manda: And I’m thinking for people listening, it sounds a very linear path and it sounds like definitely there are challenges, but they’re there to be overcome. I’m guessing that at times in the beingness of this path, with you being on it, there are times where you feel like you’re taking one step forward and six steps back. And it’s not always obvious at the time that the obstacles will be overcome. Is that fair?

Alan: Yes, absolutely. There’s moments of doubt. There’s times of real questioning. It’s like, OK, the universe has given me this feedback, and thrown up this obstacle. So what I learnt very early on in my time at Findhorn is those situations at the time to actually go back within. To turn within, to reconnect with my heart, with spirit, to ask for a dream, or to meditate, or to go out and be still in nature. And remember, this is what I said I would do. Does this still feel right? Still one hundred percent behind this? Is my heart still engaged? And if the answer is yes, there’s always a way forward. It may be unexpected, it may come from left field, it may be something initially I think is ridiculous or that’s not what I want to do, but it’s the way forward and the energy flows. And to me, I use the example sometimes, it’s like rain on a mountaintop. If rain falls on a mountaintop, it falls and it percolates into the soil, and gravity pulls it downwards, and it will pull it into a little stream or a burn, as we say, in Scotland. And it’ll flow down on his way to a loch, or to the sea or to the ocean. And sometimes the flow gets blocked. There’s been a landslide. And water builds up. Pressure builds up. And eventually that pressure will, the water will flow over the obstacle or around, or underneath or whatever. So the flow of spirit for an idea when I say yes to something, my heart is exactly the same. It’s a flow. And sometimes obstacles appear, but if it’s a true flow, if it’s really spirit, there’s always a way. And my challenge is to find what’s the way. And the obstacle is the learning process. Everything has a purpose in my life. Everything has a place, including all the negative things and the bad stuff. And often those things, I have the greatest opportunity for learning.

Manda: Yes. And I think it’s really important to let people know that there is difficulty and bad stuff, but that cultivating the ability to ask the question, is my heart still engaged? And know when we’ve heard the true answer to that, seems to me at the heart of what you’re doing and who you are, and the astonishing things that you’ve achieved, and lived through in a way of living, that is.. you are walking your talk every moment of your day. But that requires knowing how to do that in the first place, which is, you know, still quite a learnt skill. But the fact that it’s possible to learn it feels to me really important for people listening still. So you’ve got this idea, we’re going to move on in a moment to this vision of uniting all of the nations of the world in a project to restore the earth that makes my heart sing very loudly. How is that going? How are you getting on with that?

Alan: Well, I’m not doing much about it at all at the moment, to be honest, in any direct way. For several years, I put a lot of effort into it. And this was in the 1990s because we were coming up to the new millennium and you know, there was all this thing about the turning of the millennium. So I wrote articles, I initiated the Restoring the Earth project. I got somebody here in the Findhorn Community working with me on it. And we started lobbying. We went, we started lobbying the United Nations Environment Programme unit because it’s the U.N. that declares International Year of Peace or International Decade of Indigenous People. So we started lobbying UNEC. We went to Nairobi, to U.N. headquarters and took part in a workshop there. We went to the world’s first meeting of environment ministers that was held in Malmo, in Sweden in 2000 or something like that, or 2001, I can’t remember exactly when, and put a lot of effort into that. And I got a lot of prominent people to support the declaration, to put their name to it. And it didn’t really go anywhere. We didn’t get the UN to pick it up. So we organised a conference in 2002 at Findhorn called Restore the Earth, and acting on Gandhi’s principle ‘be the change you want to see in the world’. We said, we’re not going to wait for the UN to make this declaration. We’re going to declare it. So at the end of the conference, we declared this is the Century of Restoring the Earth. So not much happened, until two years ago. And basically the person I was working with, he moved on to other things. Trees for Life was growing and taking up more and more of my time. So it just kind of got shelved. We had a website; out of the conference came something that was one of the ideas, was to have something called the Earth Restoration Service, which would engage, be a bit like the Peace Corps or Voluntary Service Overseas, that would engage people taking part in restoration projects around the world. So that was set up after the conference. Still exists, but it’s been transformed into a project that works with schoolchildren to get them involved in tree planting as part of restoration. But seeds were sown. And about three years ago, El Salvador, the smallest country in Central America, unexpectedly made a proposal to the United Nations that there should be a decade on ecological restoration.

Manda: Well done. Yeah.

Alan: Now, I have had no contact with El Salvador. I travelled there briefly in 1975, but a seed was sown, and that country’s picked it up. And that proposal to the UN was accepted. And as you you may know, the years 2021 to 2030 now is the UN Decade on Ecological Restoration. It’s not a century, but it’s a start. A decade. So this highlights one of the other things I’ve learnt. Everything is interconnected. Humans, despite our illusions that we’re separate, we’re part of the web of life. And when we consciously engage with it, and when we nourish the web, unexpected things happen. Energy flows, and pops up in unusual places. So that’s happened. There’s also an organisation now called Ecosystem Restoration Camps, which I’m an advisor of, set up by a man called John Liu, who made a documentary. He’s a filmmaker. He made a documentary about the restoration of the lowest plateau in China, the huge success of healing a very wounded part of the planet. And that documentary inspired a lot of people. And he’s now set up this organisation called Ecosystem Restoration Camps, which is setting up camps around the world where people can go and volunteer to restore degraded ecosystems. So these things are happening. And I sowed a seed, and it’s, I mean, other people maybe had similar ideas, because many people feel the pain of the planet and feel called to act. Restoration projects have sprung up spontaneously in many parts of the world. And there’s a big organisation in the US called the Society for Ecological Restoration. And now we’ve got Rewilding Europe, we’ve got Rewilding Britain. And it’s really, there’s a grassroots movement that is spreading and touching people. I sowed a seed, and it’s taken on a life of its own, literally. And, you know, it is great to see it, and see what’s happening with it.

Manda: Yeah, I just looked up, I just Googled Restore the Earth and I got to restoretheearth.org, which is an American 501c, but they’ve got Coca-Cola, and Veolia and various people as their partners, and Shell, bizarrely enough. So it’s yeah, the idea: you sowed the seed, the idea is out there. So we’re running to the end of our second hour. You said way back halfway through podcast number one, that Findhorn had three working principles, one of which was that work is love in action. I’m just very curious to know what the other two are. I’m sure I could look it up, but can you tell us?

Alan: One is deep inner listening. And the second one is creation with nature, we talked about it. And then the third one is work is love in action: that everything we do should be done as an expression of our hearts. And if you think about it, that one there, if that was applied universally, the world would be a totally different place.

Manda: It would, wouldn’t it? Yeah.

Alan: A lot of the bad stuff would just fall away overnight. How many people do a job their heart is not in? I did that when I worked for this exploration company for the mining companies. My heart wasn’t in it, but I was doing it because it paid well. How many people are in that situation? Because in those days, I was still operating on the old thinking that my sense of well-being and security depends on money. And most of that is based on that illusion at the moment. It is an illusion. Money is an abstract concept. It used to be gold coins. Then it became paper bills. Now it’s digits in a computer. That’s all. And it’s manipulated. My true security has nothing to do with that, and also doesn’t have to do with other physical things. You know, it has to do with how aligned am I with my heart, and how much of my spirit is alive in my life each day? And what I wanted to do, and as we’re drawing to a close, this is maybe a good thing to bring in at the end, is talk about power.

Manda: Yes, please do.

Alan: I’ve been talking about finding my personal power, you know, starting Trees for Life with nothing. And look at it today. You know, that’s my power. What is that power? It’s the power from within. It’s the power of spirit. It’s the power of the universe. And that power is very different to most expressions of power in the world today, because that is the only form of power that we experience. It’s the power over. So it’s power of the rich over the poor. It’s the power of men over women. It’s the power of whites over coloureds. It’s the power of humans over nature. And as we’re seeing at the moment, it’s the power of governments over their own people. And that power is power which benefits a few at the expense of the many, and it suppresses and diminishes those the power is imposed over. The power from within is something completely different, because that power is the power to be myself: self with a capital S, the spiritual Self, the big Self. Not the ego, not the personality, but my true Self. And that power does not diminish anyone else. It has the opposite effect. It touches, inspires and encourages, and draws out the same power that is in everybody else, because we all have that power within us.

And this is the pivot point I think we’re at in the world today. The transition from the old world, which is built on those structures which have now become totally crystallised: governments, corporations, military, international institutions, and you know, I spent my teenage and early adult years as an activist, trying to get them to change, and nothing changed. They’ve become more extreme. And we see that all over the world today. The power structures are heading for self-destruction. And what we have to do is create a new culture that is based on this different form of power, the power of love and spirit from our hearts, that’s expressed and embodied in each individual life. When we have a world that’s based on that, it is going to further every individual in their own life journey. It’s going to heal the planet, and it’s going to totally transform the human experience on Earth. You know, that is how I see myself serving. The whole world goes back to this other thing of fulfilling my potential of who I really am.

Manda: And then Findhorn, where clearly pre Covid a great many people would come to visit. And I’m assuming in the Covid times, things have moved on to remote connexions on Zoom. Are you seeing any change in the numbers of people who are understanding what you’re saying?

Alan: I see a lot of people changing in the world. I see a lot of people taking initiative and doing their thing. Some of them come through Findhorn. I went back to Auroville last year for the first time in 20 years. I was there actually when the coronavirus epidemic really hit, and I got one of the last flights out of India before it shut down, before they closed up. I just made it out. So I see Auroville has grown spectacularly. It’s touched many people. It’s having an influence in India. I see the network of communities, a Global Ecovillage Network, GEN for short, that Findhorn and Auroville are both part of, has really grown and flourished. I see a huge amount of positive things going on, very little of which is visible in the mainstream media, which is because of its negative focus. It’s focussed on death, destruction, crime, disaster, violence, etc. A few positive things get out there. But they’re far away. But there’s this alternative network, of which your podcasts are a part, and many other people are spreading the word. And I describe it as being a bit like a forest. When we go into a forest, what do we see? We see the trees. We might see the birds, we might see plants, we might see an animal, a deer or a squirrel. What we don’t see most of the time is the fungi underground, the network. And occasionally, yes, the mushrooms appear in September every year, but the network is there all the time. So we’ve got this network of people, of organisations, individuals, Findhorn yourself, all the other people working on this. We’re not very visible to the general layman, but when you connect the network, you find it. It’s there.

Manda: Yes. And the forest wouldn’t live without it, actually.

Alan: Yeah. I have this image I’ve used many years in my talks at Findhorn of this change, and I think of our mainstream, dominant culture as being like a skyscraper in New York. New York is where I heard about Findhorn. So, you know, there is a connexion, but it’s like the Empire State Building. Our culture is linear, it’s concrete, it’s masculine, it’s disconnected from the Earth. That’s how I see our mainstream culture. And it’s old, and it’s beginning to crumble. And there are cracks in the culture now. There are cracks in the Empire State Building, in my image, in the skyscraper. If you look at the cracks, you can see, well, there’s a little green there. It’s a bit of a weed growing in the cracks. And over time, the image progresses and the cracks get a bit bigger. You see, actually, it’s not a weed, it’s a leaf. And the leaf is attached to a twig, and there’s another leaf in another crack nearby. And over time, the image progresses from being this building with cracks in it, with a few leaves appearing, till one day, we see it with a different eye. And it’s suddenly, through a gradual change, there’s a tree with the walls of the Empire State Building hanging off its branches. It’s like, oh, yes, I can see this change has been underway for a while, but it’s only now just reached that critical point. And that is where I think we’re approaching on the planet today. The dominant culture is the Empire State Building. And the alternative things, you know, is the tree growing inside it, which has a leaf at Findhorn, a leaf at Auroville, a leaf at Accidental Gods podcasts, and your local health food shop, and meditation class, and permaculture, and all those other things that are pioneering the new way to be in the world. That respect nature, that respects each individual contribution.

Manda: Yes. And allows people and the planet to flourish.

Alan: Yeah, exactly. And, you know, we’re approaching that point. And the question is, are there enough of us engaged in that other to make it strong enough that the tree will support will support itself? It won’t be dragged down by the falling walls of the skyscraper.

Manda: But every person who makes a commitment to listen to their heart and follow it as part of the tree.

Alan: Exactly. And the tree will not become fully itself and reach its full potential until everybody lives there, part of it, puts their piece into place. What is it in us? That’s the thing I would say to your listeners. If you’re wondering what to do, ask yourself this question. If there were no obstacles in the world, if there were no problems, no limitations, what would you be doing? Because that’s exactly what you should be doing right now.

Manda: Yes, that is a perfect place to stop. Thank you so much, Alan, for your wisdom, and the gift of your time and your clarity. And for that for everybody listening, just that question: ask it of yourselves, and do whatever arises is the answer. That is brilliant. All right, we will stop there. Thank you.

So that’s it for the second part of this conversation with enormous thanks to Alan for expressing so clearly the core of what it is that we need to do at this time in this place, in this world with our lives. I cannot think of a better time to ask yourself that question. What is it that I would do if there were no constraints? None. What is it that only I can do? That I can do better than anybody else and that will make my heart sing? And then go and do it, because the world is changing so fast, and there are no second chances. It is a huge cliche that life is not a dress rehearsal, but it is true. And we are in a world where everything is in flux, and the more of us that can be part of that tree that is part of the Empire State Building, while the rest crumbles, the more chance we have of a generative future, not just for us, but as Rupert Reid said a couple of weeks ago, for all future generations. We are needed to be the best that we can be, here and now, and Alan has told us how to do it.

And if you weren’t able to be part of the gathering that we held last Saturday, then I am giving serious thought to running a similar course for probably an hour and a half, probably on a Wednesday evening U.K. time, starting probably in the summer. I’m not sure exactly when, but I will put up details on the events page of the website, which is accidentalgods.life. If you think that’s something you’d like to come along to, if you think it would be useful, if you want to have any input to that, the email address is manda@accidentalgods.life All one word, all lowercase. So that’s it for now, and we will be back as ever next week with another conversation.

You may also like these recent podcasts

Emergence from Complexity

Emergence from Complex Systems is a thing. And the thing about it is, that there are only two options when a system reaches maximal complexity: collapse to chaos and extinction OR emergence to a new phase. We prefer the second option, so this episode looks at Complexity – and how to use the levers of change in any system

This Civilisation is Finished? An interview with Professor Rupert Reid

If Professor Rupert Read is right, our civilisation is finished. We’ll either collapse, or transform to the point of being unrecognisable. So… this being the case, what can we do? Join us in this discussion of how we can move forward.

Dreams of Divinity: Rabbi Jill Hammer on mysticism & the meaning of life

Rabbi Jill Harmer is committed to an earth based and a wildly mythic view of the world in which nature, ritual and story connect us to the body of the cosmos and to ourselves. We explore the meaning of life, the role of dreams and how we might find hope in the face of climate breakdown.

Finding peace in the face of Coronavirus

VIDEO – Sometimes we need a place of sanctuary – a place of healing, stability and peace…

STAY IN TOUCH

For a regular supply of ideas about humanity's next evolutionary step, insights into the thinking behind some of the podcasts, early updates on the guests we'll be having on the show - AND a free Water visualisation that will guide you through a deep immersion in water connection...sign up here.

(NB: This is a free newsletter - it's not joining up to the Membership! That's a nice, subtle pink button on the 'Join Us' page...)