#297 Otterly Amazing! Common Sense Farming can feed us all with Charlie Bennett

“In a world where our wildlife is becoming extinct at a frightening rate, we are setting up an oasis where animals, wild flowers and even ancient fungi can thrive.” Charlie Bennett writing of Middleton North Farm.

It’s clear to most of us that the existing food and farming system is unsustainable. What’s less clear is what to do about it, particularly when the behemoths of the industry put so much time, effort and money into propaganda which suggests we can’t feed humanity unless we keep doubling down on the industrial systems that are destroying our soils, our watercourses and our health. Given this toxic mix of misinformation, government bureaucracy and algorithms engineered to keep us at each others’ throats, it’s not surprising the waters are muddied.

And yet the signposts are out there and brave pioneers across the continents are working to find ways to feed people healthy, nutritious food at prices they can afford while also building soil, increasing water uptake —which is another way of saying we’re reducing flooding— and returning life to the land.

One of these glorious pioneers is Charlie Bennett of Middleton North farm in Northumbria.

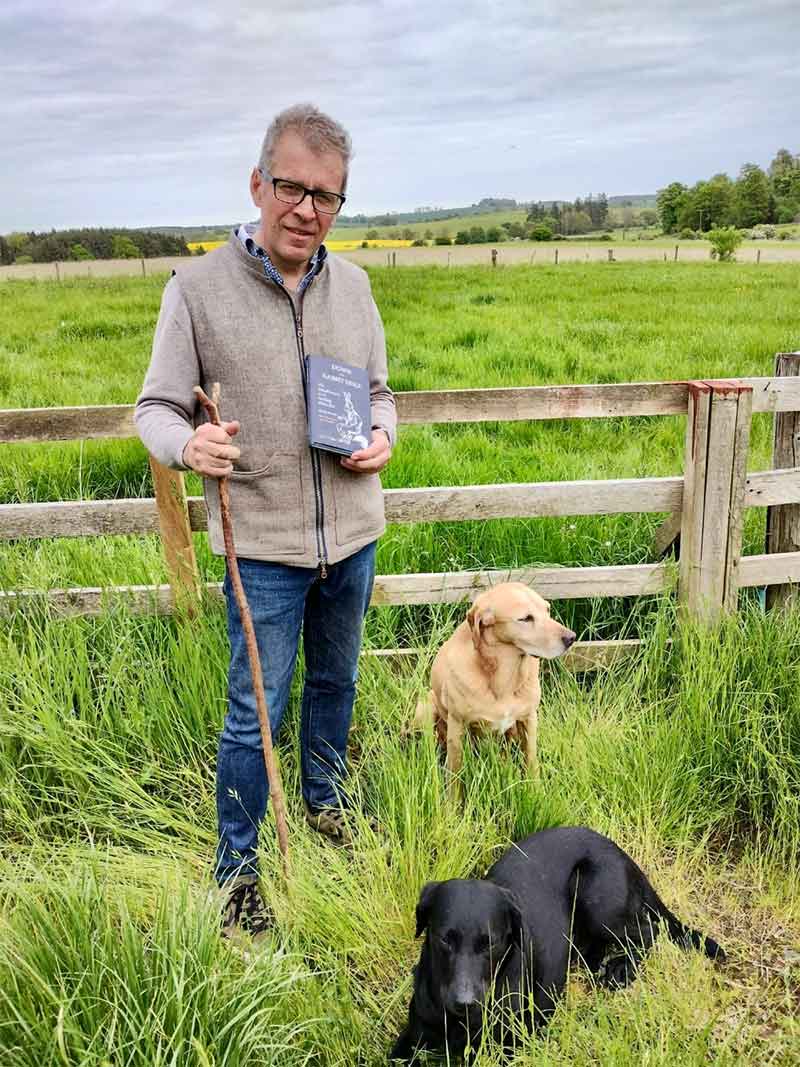

I came across Charlie in the closing days of 2024 when I read his first book Down the Rabbit Hole and promptly bought copies to give to all my friends. HIs writing was at once lyrical and grounded in a reality I recognised—and he was writing about regenerative farming, except he called it ‘Common Sense Farming’. I wrote to him then, and we’ve corresponded ever since and now he’s this week’s guest on the podcast.

Charlie Bennett is a farmer, writer, and passionate advocate for the countryside. He is joint owner of the Middleton North estate near Morpeth, Northumberland, in North East England. Here, he and his wife Charlotte work to support existing wildlife and attract new species alongside sustainable stock farming designed to add to the diversity of wildlife in the area.

Trigger Warning: Charlie and I share a passion for the land and a deep sense of connectedness to the more than human world. We both live in a reality where humans (sometimes) eat meat so if discussions of the reality of this might be difficult for you, please skip past those bits. Otherwise, please do enjoy this exploration of how we can share our world differently with the Web of Life.

Episode #297

LINKS

What we offer

If you’d like to join our next Open Gathering ‘Dreaming Your Death Awake’ (you don’t have to be a member) it’s on 2nd November – details are here.

If you’d like to join us at Accidental Gods, we offer a membership (with a 2 week trial period for only £1) where we endeavour to help you to connect fully with the living web of life (and you can come to the Open Gatherings for half the normal price!)

If you’d like to train more deeply in the contemporary shamanic work at Dreaming Awake, you’ll find us here.

If you’d like to explore the recordings from our last Thrutopia Writing Masterclass, the details are here.

In Conversation

Charlie: If you get the soil right, you get the insects right, you get the birds right, you get everything. So the soil is what it’s about. And the soil is an organ living in my mind, like a living organism, like the Great Barrier Reef, and you can get into sort of microrisal fungi and all these sorts of things. I’ve tried writing about the soil and it’s a difficult ask. But I think the thing to do is to show people the rest of what happens with it. The rest of the story.

Manda: Hey people, welcome to Accidental Gods to the podcast where we believe that another world is still possible. And that if we all work together, there is still time to lay the foundations for a future that we would be proud to leave to the generations that come after us. I’m Manda Scott, your host and fellow traveller in this journey into possibility. And as most of you know, I live and work on a small holding in the west of England, right on the border with Wales. We are a very small, small holding, and this is not how we make our living, which leaves us free to do our utmost to work with the land to see what we can do to increase the life here, to be connected to the spirits of this place in this time. And this feels to me increasingly important in a world where I think it’s clear to almost all of us that the existing food and farming systems are utterly unsustainable. What is less clear to a lot of people is what we can do about it, particularly when the giants of the food and farming industry puts so much time, effort, and money into pedalling propaganda, which suggests that we cannot feed humanity unless we keep doubling down on the industrial systems that are destroying our soils, our water, and our health. And clearly this is untrue. But given this toxic mix of misinformation and the government bureaucracy and the algorithms engineered to keep us at each other’s throats, it is not surprising that the waters are pretty muddy in this regard. And still the signposts are out there and there are brave pioneers across all of the continents working to find ways to feed people healthy, nutritious food at prices they can afford, while also building soil, increasing water uptake, which is another way of saying we’re reducing flooding and returning life to the land.

And one of these pioneers is Charlie Bennett of Middleton North Farm in Northumbria, which is right up against the borders of Scotland, for those of you not familiar with UK geography. I came across Charlie in the closing days of 2024 when I read his first book ‘Down the Rabbit Hole’, and promptly connected to his website and bought half a dozen copies to give to my friends. His writing is lyrical and beautiful and inspiring and still grounded in a reality that I recognized he was writing about regenerative farming, except he calls it common sense farming. So I wrote to him and we’ve corresponded ever since. And now he is this week’s guest on the podcast.

So to give you some background, Charlie Bennett is a farmer writer and passionate advocate for the countryside. He is joint owner of Middleton, North Estate, near Morpeth in Northumberland in Northeast England. Where he and his wife Charlotte, worked to support existing wildlife and attract new species alongside sustainable stock farming designed to add to the diversity of wildlife in the area. And he says on the farm website, ‘in a world where our wildlife is becoming extinct to, to frightening rate, we are setting up an oasis where animals, wild flowers, and even ancient fungi can thrive.’

So this is a really down-to-Earth podcast, and I do need to give a trigger warning. Charlie and I share a passion for the land and a deep sense of connectedness to the more than human world. And we both live in a reality where humans are omnivores and sometimes eat meat. So if the discussion of the reality of this might be difficult for you, then please skip over those parts. Otherwise, please do enjoy this exploration of how we can share our world differently with the web of life so that everything thrives. The sound at Charlie’s end was a bit echoey, but Alan has done his best and we are not editing out any sound of the thunderstorms because we do need the rain. So here we go: People of the podcast, please do welcome Charlie Bennett of Middleton North Farm, author of Down The Rabbit Hole, and of Climbing Styles.

Manda: Charlie Bennett, welcome to the Accidental Gods podcast. It’s been Christmas since I got to know about your book and it’s July and we’re finally here, which is my fault for booking things way too far in advance. How are you and where are you in the farming year? In the farming world? As we have lots of good hay making weather and no water. So not enough hay.

Charlie: Yeah. I’m on my farm in Northumberland. And it is midsummer and we are making hay. Probably not as much hay as we’d like because it’s just been very dry. We haven’t really had any rain since February, I don’t think but yeah, the farm is doing well because I’ve been doing this properly since about 2019.

COVID was when it really happened. COVID killed my recruitment business for obvious reasons. And at the same time, there was a tendency on our farm and I thought, let’s go back to taking the farm in hand. I just read the book, Wilding by Isabella Tree. I picked that up on the train station at Kings Cross from WH Smith, and I don’t those of you have been to Newcastle – it’s a three hour train journey. I was still reading the book when I got to Newcastle, so I sat on one those horrible metal benches. And I finished Wilding on the station and left when the cleaners just about chucked me out. But it had a profound effect on me, but fortunately I was able to sort of distil what I needed from it.

So our farm is not like that. We’re not totally gone wild. We are a sustainable farm that produces food, which is sort of my mantra really. Uh, but the environment is equally as important. So I treat the environment as a crop. It’s not as a separate identity. It is very much part of what goes on. So any decision making that happens, happens around the environment and making food. So that’s what I call common sense farming. So I’m not wilding and I’m not industrially farming. I’m doing something else.

Manda: So for people who are not familiar with, um, with KNEPP and Isabella Tree, because half of our audience is in the UK, but the other half is spread around the world. Tell us just briefly what you got from reading that and then the, the thinking that took you in a similar but slightly different direction.

Charlie: KNEPP is an estate in Sussex. And from a farming point of view, it never really worked.

Manda: It a big estate, it’s like three thousand acres.

Charlie: 3000 acres. That’s right. And it was mainly arable and very heavy clay soil. And they might get one good crop in seven years or something like that, and it didn’t work. And the people that own it had a sort of, uh, I think they just, you know, got lost it with it and thought, let’s just let it go. And that, this is a huge generalization, but it’s what they did. So they took away most of the stock, they let all the crop land go back to being meadows. They let all the hedges grow. They brought in things like pigs to help, you know, dig everything up. They just let it go and let nature take it back, which is what it’s always wanting to do. I mean, if you look at Chernobyl, for example, Chernobyl is one of the biggest, most amazing wildlife areas in the world now because of what happened. You know, sadly what happened to it, the humans left and guess what happened? Nature takes it back, doesn’t it? And actually, oh that’s another red herring, isn’t it? But, anyway, that’s what they did at KNEPP and what I also saw when I’m comparing it to my father, my grandfather, who’s my big inspiration, amazing guy. He was an amazing countryman and if you went looking around a farm with him, he’d also be showing you, oh look, a mole has come out of that ditch to have a drink. Or that’s where a barn owl has been. Or Charlie, do you know that this is what, what this hedge plant is? So he was totally ingrained in the countryside and uh, I dunno what it was when I went read the book and saw KNEPP, it just brought everything together. So, and if I’m honest, some of KNEPP is quite scary. You feel like you’re gonna be jumped on by a leopard.

Manda: Have you been down to one of their safaris? Because they make most of their money now with people going on actual safaris in the English countryside.

Charlie: Well, they do well. Jason Emrick, who’s the agent there, he’s a great guy. He’s a fellow godfather with me to a friend of mine’s son.

Manda: Oh, that’s handy.

Charlie: And when it came, I phoned him up and I said, Jason, I’ve got to come and I’ve read the book. I need to come and look. And he said, you can’t, it’s fully booked. I said, I’ll tell you what. I went to the confirmation and you didn’t. So he said, okay, fair cop. And so I went, and again, a bit of an aside, but the really important thing that, what’s so clever about Charlie Burrow is that the first thing he talks about is the money. So it’s not a rich man’s dream or a play thing. It’s very much centred around actually working. And we may come and talk to this, but it is so, I guess to a certain extent around being helped by government subsidies, et cetera. But the model I guess since then has very much been around tourism and workshops. And so it has wiped its own face, um, and it kind of works for that

Manda: And, it’s done amazing things to biodiversity. They’re seeing species there that they’ve never seen before, and I think they’re proving quite a lot of stuff in terms of, so they have Longhorn cattle, the ponies, they brought in Exmoor ponies. And one of the things that I find really interesting is we, we have an epidemic of the equine equivalent to diabetes in this country and, and laminitis and swish and all of the things that are basically the result of a poor biome because we think our ponies and horses like eating beautiful green grass that’s monoculture and, you know, half an inch long and, and then come in and be fed a bucket of oats. And I’m generalizing, and please horse people don’t write to me. I realize that’s not exactly it, but that’s the basic. We feed them cereals and monoculture grass and at KNEPP they are a browsing species

Charlie: Yeah. I mean that, yeah, horses. I mean, I was saying to somebody yesterday, again, apologies to anybody who does this, but, um, I can’t stand seeing horses on their own in fields.

Manda: No, no, no. It’s a disaster.

Charlie: They’re usually on a billiard table. Um, and they’ve, you know, they’ve, they’ve got a corner in the corner where they won’t eat because it’s where they pee and where they, where the docs live. So if you let things go, I’ll give you an example of this to take it the other way. On one of our fields, we didn’t cut it, we put it back to grassland, which called GS4, which is legume rich meadow land, put it back, and then for one reason or another, we had a really bad year and we couldn’t make any haylage, blah, blah, blah. So we left it, it’s about 40 acres and we went for a bird count and we counted 300 yellow hammers in one corner coming out of – and there are other reasons they, we don’t cut our hedges because we’ll cut them this year, but it’d be the first time in five years. because if you cut a hedge every year, for example, a lot of our hedges are Hawthorne. If you cut Hawthorne every year, you cut the flowering part of it off. So you don’t get any flower. You don’t get any berries. So the only reason hedges get cut in my mind is because it’s something to do in, in the winter. And farmers don’t like to be accused of being untidy.

Manda: They have this idea that it has to look neat, that their neighbours are going to look over and look at it. We’re going to talk about thistles in a moment. because I basically seem to be a thistle farmer at the moment. And then neighbours hate it. And every regenerative WhatsApp group I’m on goes, you have to learn to love thistles. And I’m like, please… because KNEPP had this thing where they were being thistle farmers, and then they had this day when the monarch butterflies all turned up and, and basically laid the caterpillars and, and munched away the thistles. I just keep looking going, where are the butterflies? They

Charlie: Well, this year been bad. And the thistles and the docks have tap so they, they’re happy as Larry. I have a mixed relationship with thistles in that we grow our hay to sell. And I don’t want it full of thistles. Um, it’s just not, it’s just not nice for animals to eat or to handle.

Manda: Or for people to be picking up the bales and trying to move them.

Charlie: Exactly. You know what it’s like, it’s horrible. So I’m not, but where there’s a corner, I’ve got lots of corners. because this year, as you say, they’ve done so well. I do worry about they, all those thistle downs going to blow onto my neighbour’s crops. But what can you do? You know?

Manda: But also, somebody told me there’s something ridiculous, like 4,000 dock seeds per small amount of soil. It’s not, the seeds blowing off are not it. If the if the soil needs docks, the docks will grow provided you’re not spraying the heck out of them to get rid of them. We’re probably getting a little bit too detailed for people who had no idea what we’re talking about. I would have this conversation forever, but let’s take a bit of a step back. How, how big is your farm and what are your principles of farming it?

Charlie: Okay, so I call it common sense farming Manda. So we are farming for food, which I think is super important because sustainable food is harder and harder to get at. We’re a very, if you ever fly over this country, and I asked you what colour is it? What colour would you say it is?

Manda: Well, just at the moment, it’s brown, but it’s usually green.

Charlie: It’s usually green, isn’t it? And the reason for that is because it’s, it’s in a perfect spot. It’s in a goldilocks zone, if you like, for growing food. And that is, whether that’s crops, animals, bees, lettuces, whatever. I wrote an article about a history of one of my fields going back 10,000 years. And the first people that came on were hunter gatherers, or, you know, foragers really. But then they did, we do know in Northumberland that farming came pretty early on in terms of farming. You’ve got to understand too, about global warming. Northland, for example, when the Romans were here, was three degrees warmer than it is now, right? So we’ve been through these things before and I’m not going to get into that,

Manda: Don’t get into here because by the time it gets 10 degrees, there is no complex life left…

Charlie: There’s been times in history when it’s worked for farming and it’s gone back a long way. And, and that’s because this country works quite well for grain food. And our area where I live is very good for what we call finishing country. So it’s not brilliant for grain crops, but it’s very good for cattle and sheep. So a lot of our land had been, if you go back to the second World War, where I think rightly so, we were encouraged to grow more food for our country. And farmers are very flexible people, so they said, yeah, let’s do this. And they did it. But sadly, the genie was out the bottle in terms of chemicals, machinery, uh, not really understanding the importance of, of, you know, woods, hedges, ponds, et cetera,

Manda: Or soil life. Because we couldn’t measure it.

Charlie: I think that’s still the case, to be honest with you. I don’t think many people understand the soil at all. A friend up here called Tom Fairfax – I spent a Saturday afternoon with him looking through microscopes at soil and that was amazing. That is like looking at the universe. It is amazing. But I don’t know, I don’t know anybody else who’s done that.

Manda: You go to Groundswell. So for people listening, Groundswell is the big regenerative farming conference. It’s just happened in the UK as at the point when we are recording this and the, I will send you 8.9 hectare podcasts. They were talking about soil life so much through there. So I think it’s at the leading edge of the kind of early adopters are beginning to get it

Charlie: Well, my, when I give a talk about this, I call it from soil to song, and those aren’t my words, but if you get the soil right, you get the insects right. You get the birds right, you get everything. So the soil is what it’s about. And the soil is an organ living in my mind, like a living organism, like the Great Barrier Reef, and if you get it to sort of microrisal fungi and all these sorts of things – Tom, who I know, he’s amazing. He will not only tell you what’s in your soil, he’ll tell you what you are missing. And so then you can get, so what we were really looking at was composting. That was our big thing at the time, but on a farm scale, so, and I we’re trying to make a plan. So say if we came to your farm, Manda, which I haven’t been to, but imagine, which I know it isn’t this, but imagine it’s in thinking show and it’s a monoculture and it’s got concrete roads around it. What are we going to do? So what we’re going to do, in that case we’ll probably have to make some tea, some compost tea for it. We’d also have to probably move in some muck and some soil, et cetera. But we were trying to make a system where we could improve people’s soils anywhere in the country, in for anywhere in the world using what’s around us there. And the only way we could do that was for Tom to show me down the microscope to show me what was missing and what we had and what we didn’t have. And this is leading to this and that and the other. So yeah, the soil is really important, but it’s sexy. Soil’s not very sexy. Right. Red squirrels are quite sexy. You know that we can, we can talk, we can do a lot for them. I’ve tried writing about the soil and it, it’s a difficult ask. But I think the thing to do is to show people the rest of what happens with it. The rest of the story

Manda: And to do the Cotton underpants test, which you do, which we have spoken about in this podcast. So probably when this goes out, probably about six weeks ago, Tim Smedley wrote an amazing book on water called The Last Drop. And as part of that, he was looking at regenerative agriculture, obviously helps to increase water uptake by the soil. And he had a guy who was a contract farmer. He farmed three separate bits. Land one was industrial, one was organic, but with ploughing. And the other was the regenerative that is basically minimal tillage with glyphosate, which I don’t, I think we should find a new word for that. It’s not really regenerative farming, but the, that bit was the bit where the cotton underpants were eaten most. So for people who haven’t listened to Tim Smedley the last job, tell us about the cotton underpants test because I think that’s, that makes soil fun.

Charlie: One of my favourite things in the world is, um, is bringing small children onto the farm. Um, and the children that we get are from disadvantaged areas in the Northeast. And there’s a wonderful charity called Country Trust and we work very closely with them. Because bringing children from a disadvantaged urban area is like bringing them to Mars. They, honestly, it’s very different. So we educate them a bit about what they’re going to see and what’s going to happen, and then we bring them out. Uh, honestly, it’s just heaven. So they get off the bus and what I’ve learned is they just need to play. A lot of these kids don’t have the opportunity to play in a rural environment. So they just run around and go completely mad. A lot of them have never got their hands mucky in the sense of being the hands in the mud. They’ve never had a creepy crawly in their hands. So one of the things we do to sort of break the ice is we go and dig up worms and, uh, that immediately you, you are already into showing them these incredible, incredible creatures that are wriggling around. And there’s also leather jackets and all sorts of other things. So from, if you’re abroad, that’s a larval stage thing for a daddy Long legs, which is like a sort of an enormous mosquito, which can’t bite you. Crane front. Anyway, so when we’ve done that, we then we then get a pair of pants which are made of cotton with elastic, with elastic top. Like I’m sure you’re all aware. And then you bury them and you leave them for a year. And then you get some more kids to come, and they dig up the pants and all that’s left is the elastic. And I always joke with them, I’ll put the pants on and I’ll put them on over my clothes, I’ll hasten to add. And, but the kids just get it immediately. Because what has eaten the pants is the worm. And we’ve seen in five years, we’ve gone from having pants and a bit of material to just the elastic.

Manda: Yes. And you mark them, obviously. Do you put a date on your marker with these kids?

Charlie: I put a bamboo cane in. I know exactly where they are. To demonstrate that what the worms are doing.

Manda: Right, and it makes soil exciting. Then soil is something that, isn’t an inert growing medium, which I think a lot of industrial farming is creating inert growing medium and is treating the soil as if it were an inert growing medium. When once you get to know, I have a friend who farms with his horses, so he’s been doing this a long time, and he says he’s a worm farmer. That’s what matters is that he farms the worms. Everything else depends on that, and he’s been doing that for 40 years, but he’s kind of on his own.

Charlie: Well, he needs his moles as well. The other great thing under the ground is that the moles are fabulous, so they, you might not like them on your lawn. I get that.

Manda: Then don’t have a lawn, that’s really easy. Just let your lawn grow and you won’t notice any moles.

Charlie: Well, my view is I get that, but they irrigate. They also, which is the most amazing thing, is that they carry the spores of microrisal fungi in their fur. So they’re taking all the good news from one place to another, particularly on the edge of woodland or two woodland. And they’re just, you know, they’re fabulous little creatures. And so we’ve seen them. They’re also an indicator come back to, I was saying earlier, we took a lot of our arable back and put it into woodland, and there were very few molehills in it to start with. Now it’s absolutely stuff for them, which tells us the worms have come back into the soil. But anyway, the moles are then an indicator that we’ve got our worms back. So they’re are, they’re little flags saying, yeah, you’ve got some worms back. So a big mole fan.

Manda: They sound much, much cuter than something that you skin and turn into a jacket. Just for context, I still don’t know how big your farm is, but your farm was in the family and your grandfather farmed it and then it went out to tenant farmers?

Charlie: No, it’s a very interesting story. So my farm, our farm is my wife. My wife and I’s farm is, uh, in 1923, her family bought the farm or bought a part of it. We’ve got, I won’t get too complicated, but anyway, the guy that bought it then died and his, he, his son died as well in the war, first World War. So his daughter took it on. Then her boyfriend in the second World War died. So she then passed it to my mother-in-law who’s then passed it to her daughters. So we have a total matriarchy.

Manda: Fantastic.

Charlie: I think it is fantastic because, and the one word I would take out of all of that is empathy. because it’s not been a patriarchal, uh, you know, you know, the school kind of thing. But it, it’s been much more sympathetic. And I think I wouldn’t have been able to do, I don’t know, to be honest, but I don’t think I’d be doing what I’m doing now if there hadn’t been a matriarchy before me. So if you talk about Mother nature, then –

Manda: You’ve got the mothers.

Charlie: yeah, there you go. Hundred percent.

Manda: Okay. And so you came back and you’d read Wilding and it sounds like there was quite a lot of arable land. That’s not, it sounds quite clay land from what you said about in other things. It’s not ideal for arable and your decision was, let’s see what we can do. Create food for our local environment, presumably, and hand rewild as much of the land as we can, or at least increase biodiversity while increasing food. So you had, the arable was quite industrial, was it? Was it plough and spray? Industrial arable? So cancel that plant load of trees and bring in more finishing livestock. So beef and sheep?

Charlie: Yeah. So the arable land went to, um. All these things have letters because it’s the government that organizes, it’s obviously nonsensical. So it’s called GS4, which is basically herbal rich lays, which means, so you’ve got about seven species of grass, and you’ve got things like birds, foot trough oil, different types of clover, uh, and they’re, they’re putting nitrogen back into the, into the soil. So they’re reading that. We’ve also as I said to you by earlier, by leaving it for a few years, it’s created a thatch, a thick thatch.

Manda: And you must be getting increased species because we’ve only been working here for seven years. We went from not very many. We’ve got 78 different species on the hill now. But I know there are places not too far from you where they have 60 or 70 per square meter on areas that are so steep nobody’s ever ploughed them. And, and those are SSSI. Now that’s – for people outside the UK – that’s a Site of Special Scientific Interest. And they collect the seed and that seed is gold dust. Because they have so many species. So I’m thinking by now you’ve got way more than your GS4 seven kind of lagoon-based species in there.

Charlie: So nature will just come, won’t it? You know? And so we’ve got plants in there like, Tanzie, uh, Yarrow, all kinds.

Manda: We get loads of plantain this year. Do you have yellow rattle? I get very excited by yellow rattle because it parasitizes on the ryegrass.

Charlie: We’ve got this wonderful meadow, which has not been farmed for 50 years, right? And people come along and go, why don’t you put yellow rattle in here? And I said, because it’s not here.

Manda: Also, if you don’t have ryegrass, it doesn’t need it. Ryegrass is a really toxic thing that you don’t want to have around. And yet it became the end thing because it grows, it grows well with very short roots, which is the opposite of what we want. But if you don’t have ryegrass, you don’t need yellow rattle.

Charlie: Yeah. Don’t do it. Yeah. So we, we don’t have that, we don’t have any rye grass in that sense. I had the woodland Trust round this week and we were looking at the woods that we’ve been planting. And I was saying the plot, the trees that are doing really well are alders. And they’re normally, you know, water loving trees by, but they’re doing well everywhere. But what Rachel said to me was, they’re kind of like a, a pioneer tree. Like a birch. They’re not very long lived, but what they do do, is they fix a lot of nitrogen in the soil. They grow a canopy very quickly. And so the other longer growing trees like oaks and beech and other things like that are in a little bit of a nursery if you like, looked after, which comes to a really important thing is how long is your plan, right? So we might come and talk about this in a minute, but Coca-Cola have done a lot with me and the CEO of Coca-Cola said, how long is your plan? I said, it’s 200 years. And I said, how long is your plan? And he went five years. because that’s what happens in a business cycle or sadly in the political cycle. He said, why is it 200 years? And I said, my reason it’s 200 years is because I want to think beyond me and I want to think beyond my children’s generation. And weirdly that’s half the age of an oak, right? So, so an oak, an oak at uh, 200 is like, I don’t know, in our time, 40 or something.

Manda: It’s at its peak of maturity.

Charlie: That’s it’s peak. So if you can project that far ahead, then you see the world in a very different way. And that’s what’s very interesting about the woodland is it’s not fixed in time. It’s something that’s going to develop and grow. And go back to the fields. So we might start off with those seven species, in 10 years, we might have seven species, but they might be totally different.

Manda: Right, right. Yes. And by then the thistles hopefully will have made a succession also. I’m really waiting. I, I might, uh, Faith and I have conversations about that all the time of ‘You need to cut thistles out’. And I go ‘No, please, I’m told that we will grow to love thistles and that they are successions species.

Please, can we just leave them for a little while longer?’ There’s lots of thistles. Can I ask a little bit about your relationship with Coke? Because that, again, is a conversation Faith and I have, and I’m at the, if Coke wants to pay us to put 20 ponds on our land, the fact that they’re basically bottling diabetes and that they would be, if we are going to get to a sustainable future, Coke and Pepsi need to cease to exist, or at least they need to change. They could be selling people water kefir or kombucha. They don’t have to sell basic poison to people. But given that I can’t change their business model and they have a huge amount of money, they want to make my land better land, why would I complain about that? And you seem to have got a step ahead on that. You told them they were selling diabetes in a bottle, and they still put ponds on your land.

Charlie: Yeah. But they… I’ll talk about it, but the top level is a lot of those businesses get such a slagging, like Nestle and stuff, and they try and say they’re doing something good and basically nobody believes them. Right? What they do is they get on with it, they just get on with it and because they’re just, they’ve had it with everybody slagging them off the whole time. So why, why fight battles? You’re not going to win. Why not just get on with it? And what I loved about what they did was, unlike people who do what I call greenwashing, is they’ve got a policy, Coca-Colas put more water back in the earth than they take out. That is quite an ask. You can’t just turn the tap on, right? You’ve got to do stuff with wetlands, you’ve got to do stuff with rivers, you’ve got to do stuff with ponds. And they’re doing that on a global basis.

Manda: Are they doing it in the places where they’re taking the water out? Because putting more water into Yorkshire and taking it out of, let’s say Saudi Arabia, I realize that’s not what they’re doing, but…

Charlie: So, for example, they may, they’ve got a bottling plant in Morpeth, right? So doing something nearby is a good thing.

Manda: Right.

Charlie: The issue they’ve had is they want to do the good thing. Our planning system has made it really hard all around the country. I’m probably saying, shouldn’t be saying this, but I just got on with it. I asked for forgiveness later and I’m sure if there’s anybody listening to this, then you know…

Manda: Those kind of people don’t listen to this kind of podcast

Charlie: Oh, good. Anyway, so, um, we just got on with it and they were a joy to work with Manda. So we, they said, right, what, what do you want to do? I said, I want to have the ponds here. What are your criteria? I don’t want to have any straight lines. I want to have different depths. I want to do different ponds in different areas to try what’s going to happen. And you had stony gravely, boggy, blah, blah, blah. And, uh, I want to plant trees mainly on the north side of them so we can get some sun in and want to, you know, basically we – with the Northland Rivers Trust, they’re amazing – it was my partner who introduced me to them. And uh, and that’s what happened. And then we got the bill and they paid the bill and boom. And then they sent their people to come and plant trees, and then they send their global leadership team.

And then the other thing is, it then means to come back to your point is if you were a graduate looking to work for Coca-Cola and you pointed that at them to say, look, you’re making people obese and filling the oceans with plastic. They say, well, yeah, yeah, that, you know, hands up. They’ll just say, hands up, but look what we’re doing here. Or look what we’re doing here. Look what we’re doing here. Look what we’re doing here. And so I found them much better to work with than government, for example, I would, I’ve worked with them a hundred times faster than the environment agency, for example.

Manda: Right, right. Which is underfunded and hamstrung by, by bureaucrats and box tickers. And I’m guessing you don’t get to be in the operational of Coke if you’re a box ticker, you get there because you’re good at thinking innovatively. Just out of curiosity, when you say you’re basically selling diabetes in a bottle, do they show – Because I hear what you’re saying. They’re doing good stuff. But our world is beyond the point where it’s doing slightly less harm is enough. We’ve got to actually start getting clean water, clean air, clean soil, which means living soil. And you don’t get that by selling people diabetes in a bottle and chucking the plastic in the ocean. Are they showing any sign of, we understand that selling basically carbonated sugar water is not clever, but there’s other things we could be selling?

Charlie: They do. And they do because they’ve all got kids, right? And they’ve all got, and they understand that, and they’re also, they’re legislated against it with the sugar tax and everything else. So I would say, yes, you can still buy full fat Coke. You can also buy probably nearly every alternative they’ve got is sugar free, like Coke Zero,

Manda: Yeah, but they still cause diabetes. They’re still basically an ultra-processed drink.

Charlie: Then it’s a matter of choice, isn’t it? We can all wear woad and eat wood. You know what I mean? I think there’s a certain level of choice and making decisions and, and I think they, it’s really hard. I think you’re absolutely right. They are overall creating something which isn’t great. They do recognize it. I think, yeah.

Manda: I mean, because if they spent less money lobbying and less money advertising, their business would collapse, but people would be less sick. We need a new system. Let’s not head there. Let’s stay back on the farm because you’ve got, so, you got ponds and you told a wonderful story on a podcast about a water boat. Tell us about that. Because it was just heart exploding, beautiful and wonderful.

Charlie: Oh, so it is a wonderful, uh, am I allowed to do accents on this?

Manda: You can do whatever you like as long as you don’t swear.

Charlie: No, no, I’m not going to swear. So we’ve got a digger driver called John, and John is a genius. He is an artist with a digger, and he, he loves digging ponds for me because I just let him do what he likes and he has got this incredible mind which understands how a pond then blends into nature. So he’ll say to you, the pond goes here, the hedge is there, the wood there, and each one of those in his mind is talking to each other. So it’s a, it’s already a holistic relationship in his mind.

Manda: Can we borrow him when we want to put ponds in here?

Charlie: Yeah, well you can borrow, John is under big demand. He’s got his own wonderfully on the back of his digger. It doesn’t say JCB, there’s a wonderful painting of a curlew. Anyway, he dug this pond in these lovely different shapes and different LED depths. And what we did was we, we dug it next to where all the old field drains come in. So you let it come in on one side and you block them on the other side of the pond will fill up. And after about two hours, the pond had about 10 inches of water in it. And he went away. And I was just standing there thinking, this is quite nice. And then I heard this plop, I thought, what’s that? And there was this water boatmen.

Manda: Magic. And so nature came.

Charlie: I wouldn’t say in five minutes, but in an hour.

Manda: There was no pond and now it’s got life.

Charlie: If you do anything, dig a pond, you do anything at all. And I don’t care if it’s that big or how big it is because it’s not just the, obviously it’s like the water boatmen and the newts and the dragonflies and the blah, blah, blah, and the frogs. What we’ve then seen is the bird life is just exploded all the way around it. And then, and then all everything else. So you then end up with an ecosystem just from that pond, and then you then get it, then it just goes out like a ripple effect from there. Um, and that, but now my ponds are, I think I sent you a little video the other day, but they’re, they’re, um, they’re starting to get filled with segs and, uh, all these other things. And so nature’s trying to take it back and make it into a marsh. We’re going to talk this, this is when we get into intervention, isn’t it? So. We, your farm? My farm. They’re not wildernesses. They’re, they’re big gardens.

Manda: There’s cycles.

Charlie: And, and you as a human, when do you say, uh, actually I want to dig the pond out again because I want it to be back to being bobby land for water beetles. Or do I just let it go back to being a marsh, then it’ll go back to being a bog. Then it’ll go back to being land again.

Manda: Right. Because it’ll fill with leaves and everything and you’ve got very, very rich land then. But then if you allow it, the water will create another pond somewhere provided there’s enough water provided the water cycle is doing its thing, there will ponds don’t vanish.

Charlie: And I think it’ll become like a winter pond, if you know what I mean. So it’ll hold water in the winter and I think they’re called ghost ponds. I can’t remember.

Manda: I think, and they, their whole ecosystem of things that flourish in something that’s totally wet in the winter and, and basically slightly damp in the summer.

Charlie: We’d done bioblitzes with children again. Going back to the children. We found mature dragonfly larva very quickly into the, into the project, which means the dragonfly again. And, and I think we do get these amazing dragonflies called emperor dragonflies, which are about seven centimetres long. Wonderful iridescent blue body with a bright green head. I mean, I don’t know, have you ever thought about the colour of animals? But I’m not religious at all. In fact, I’m an atheist. But somebody had an imagination when it comes to those guys because they are gorgeous. But anyway, so they, they’re an early adopter of ponds, so they must have come in and gone, oh, right, this is okay. And laid their eggs in it without knowing there’s any because, obviously they’re carnivorous, so they had to think maybe there’s something in there they can eat. But yeah, within a very quick process, we had those kind of guys around. We had newts in there very quickly. But newts do go across the land.

Manda: And then frogs and toads.

Charlie: We put in a duck tube. Have you done that? So you get some chicken wire and if you roll it out and put hay on it, put another thing of chicken wire, then you roll it up like a Swiss roll, you’ll end up with a tube which is in insulated with hay. And you put that in the middle of your pond on a stick

Manda: Vertical, upright, like a tower?

Charlie: Yeah. Not very high. Only about, you know, five feet out of the water. And we did this with these kids and, uh, I was thinking there’s no way any ducks going in here because it’s too busy, you know. The next day I went down there and there was an egg in the, in the, in the nest in the thing, and one in the water, which has obviously been accidentally kicked in. And I thought, what’s this? So I put up a camera and they were led to mandarin ducks.

Manda: Mandarin ducks. Those are not they’re invasive, invasive species, but absolutely hilarious. If you’re getting a bit depressed about Trump, Ukraine, and the world watch videos of mandarin ducks. Because they’re very entertaining and they’re also bustling about, and they’re very full of their own importance.

Charlie: But there must have been 12 of them, you know, uh, having a party by our pond for about six nights or something.

Manda: So on your farm, you got rid of all the arable or just got rid of most of the arable and then brought the livestock in, and tell me how the livestock are an integral part of what you’re doing, why you want them there?

Charlie: So what I quickly learned was if you have too much stock, you end up buying what I call sheep wrecked. And so you get overgrazed, it’s not good for the stock either because they end up eating their own poo, the worm burden goes up, et cetera, et cetera. And so I, what I did was with the tenant farmers, we had, I halved the out of stock they have with us, but I also halved their rent. And I gave them twice as much land. So they were in the same position as they were originally set. They had a bit more, you know, ground to go around, but it’s not far, you know, it’s within, they can do it in a circuit. And when I first did it, they had some, sheep going into this field and the grass was 12 inches tall. And they were, you know, the sheep won’t want to eat that. They only like short grass. And I said, I’ll tell you what then why don’t you let them in? Let them in If they don’t like it, we’ll, uh, we’ll take them away. Of course, they like it,

Manda: Of course

Charlie: They’re sheep for god’s sake. So, I have to say, I think they do like short grass, I’m not saying they don’t, but they’ll eat long grass.

Manda: Well, short grass is like McDonald’s. It’s, it’s very high in sugar, but my friend who’s the regen farming people that are regen sheep, people that I’m on lists with, put them in the grass when the grass is like my height, which is five foot and you cannot see the sheep. And the sheep are very happy apart from the else they’ve got shade and shelter.

Charlie: They’ve got shade and shelter, and also the land is protected. So if it rains, and let’s say those sheep are on a hill, they’ll basically fold the grass over onto the land. So the grass is protected and the water will then filter through and you won’t end up with, you know, muddy runnels and basically run off, will you? So, and then the cattle were the same, so they were about half again. And the farmer said to me the first year, I said, you know, then nobody ever says thank you. S he actually got the best price in the market for his lambs that that time.

Manda: And are you doing mob rotational grazing or holistic planned grazing or any of that sort?

Charlie: I can’t stand that because when I had Dexter cattle, I had, I can’t remember, I had 20 Dexter cattle and they were running over about 30 or 40 acres. What I noticed is, going back to your thing about horses earlier, they are herd animals who migrate across land to get what they need. So, and it might not just be a grass, it might be a mineral. And what I noticed was that the matriarch like an elephant. She knows where, you know, if they’re feeling like they’re going to get staggers, which is a magnesium deficiency, she knows where to go and eat the right thing for that if they want to. And they also eat, the only reason we let the hedges grow is so they can gain in the right time of year, they can gain the berries off the hedges, If you mob graze, it’s like putting you on a tennis court. And so that’s where you are. So you’re not going to get what you want to eat because you’re being quite often with mob grazes, you are making animals eat what they don’t want to eat. They’re all amongst their own poo and they’ve got no shelter from sun or rain. And so I’ve got a friend who always says, Charlie, if you want to get onto this grant, you need to mob graze. Well, I’m not going anywhere near it with a barge pole. I get clear on this. I’m not an evangelist of any type of anything. If you want to mob graze, then cool. Do it. But –

Manda: No, but I think there are very good reasons not to, and I think it’s an evolutionary phase that some regenerative farmers go through and you’re not alone. I spoke to a lovely gentleman who’s got a couple of thousand acres on the side of a hill, West Virginia, um, and he goes out every evening with his wife and they put a stake in where the cattle are resting and they’re never in the same place twice, and they, they split, it is 400 acres. They split it into four lots, so they get decent hundred acres. And because they know where to browse. And I went to a webinar relatively recently with Claire Whittle, the regenerative vet who’s amazing. And she was saying that I think it’s molybdenum in the grass crashes in the spring, just when the sheep need it for lambing. But it’s 10 times the level, it was in the grass in willow leaves and provided you, you got enough, the sheep will know to go and browse the willow leaves and then, and, and then they actually get it in a bioavailable form, whereas everybody else is spending money to, to buy some and stuff it into their sheep, which basically does nothing to the blood levels, but makes everybody think they’ve done something useful.

Charlie: Well, it’s like, it’s like, um, hay made of ash trees.

Manda: Yes, yes. Used to be very common. And that was, I think that was more about being an America than that, but, these things were, well, you know, if you go back in time, you’re going back to getting common sense farming, aren’t you? What was around? Willow was around.

Charlie: Ash was around, yarrow was around. And gorse was another thing they used to use for feed as well. And all these, and my grandfather used to have a field called a medicine field on his farm. And it just had, he probably, he didn’t even know all the things were in there. He just knew if he had a sick animal he put it in there it would, generally speaking, come around again. And so we’ve got very ancient rig and furrow fields on our farm, which some of them go back to the 14th century.

Manda: You’re going to have to tell people what that is.

Charlie: So rig and furrow is like, uh, a wave – like that – of lagged. And the reason was they used to plant a crop on the top bed on here.

Manda: For people not watching the video. Charlie’s making a kind of sine wave with his arms, and it’s okay. It’s basically, it’s what it sounds like. It’s, it’s ridges that have been deliberately created.

Charlie: Like the sea and you’re looking to see, and there’s a swell going on, and you’ll see like a, or an oscillation if you like. Of, of a curve going up and down, up and down. And the top bit, if you imagine, was where they planted the crop. And this, it was very clever. I mean, you think this was in the 14th, 13th century? It’s warmer. It was, it was, uh, it was aerated, and it was, uh, irrigated and then the water ran away down the road. Very clever way of farming done with oxen. Amazing. And then what happened around us anyway, in the, when we had the black death in the 16 hundreds, I think it was, and by the way, the Black death came to us by people sending clothes from down south because they thought we were getting cold and then they’d send their fleas to us. So we all got the black death. But anyway, when that happened, everybody walked off the land and then over time they walked off the land to go into work in industry and what have you. It all went back to being grass. And that grass is amazing because of the reasons I’ve just described. So our grassland are rig and furrow will have up to 40 different species of plant in it. So that’s what, you know, what happens to it. But a lot of those plants that they put in when they then put used it as grassland, sorry, to come back to my original point, they knew some plants were menial, so you might have, you know, yarrow, I keep going on about it, but Yarrow is an amazing plant.

Manda: Yes, it’s apparently, it’s sacred in Ireland. I was talking to Diarmuid Ling a couple of weeks ago and he was saying that they do ceremonies with Yarrow because it’s so amazing. My partner did a course in herbalism, and it was taught by a guy in the states who did kind of shamanic work with plants, and it was astonishing. And he had been up a tree and had managed to cut himself with a chainsaw such that his femoral artery was bleeding. You think, okay, you’re going to die very, very fast with that. And, and they managed to get down the tree and he packed the wound with chewed up yarrow, because they knew the helicopter was never going to get to him in time and the bleeding stopped. And, and it’s apparently, it used to be, it was the battlefield herb. Every, every knight would carry some yarrow to, to plug the holes that they hacked in each other because it’s just amazing as a wound dressing. And I don’t know about you, but the ponies love it.

Charlie: So yeah, it’s nice to eat for them. They like to eat it, you know, it’s not something they don’t want to eat, is it?

Manda: All right, let’s, let’s move on. So we’ve got, you’ve got some tenant farmers and you’ve half their stock, but also half their rent and double their land. So then they’ve got half the stock in twice the area. So you’ve basically got quarter of the stocking density and they’re doing better.

I am a member of the Pasture Fed Livestock Group, which is people who, you know, basically we’re not going to feed anything except grass or hay made from that grass. Because we don’t want to give them cereals because there’s a lot of work. I don’t know how much you’re familiar with this, but, in the livestock that they eat, the grass, the omega six and Omega-3 levels are the ratio that they need to be for, for animal and human wellbeing. And if you start feeding cereals, those, that ratio inverts and is now toxic to people and animals. And that’s everything that you get from milk or cheese or butter or, or lamb or beef or whatever. So if it’s pasture fed, it’s better for the animals, it’s better for the people. So I’m guessing he got really good price just because everybody could see that his lambs were better and that the, the cattle will be the same.

Charlie: Something that really irritates me is that our stock ground us gets sold in a, a place called Linton Mart. So all these amazing animals on our land go into the mart with everybody else’s right. It’s a bit like mixing Saint Emillion wine with lemonade. So it really irritates the hell out of me because when I had my Dexter cattle, I thought the beef was delicious and my friends would say, it’s delicious. And I thought they were just, you know, they just bigging me up. So when I went on this holiday, and I took somebody else’s Dexter cattle and they all said, what’s happened to your beef? So, and then I then did an MSC in organic agriculture at Newcastle Uni and one of the, one of the professors, they said, why are you really here? And I said, I want to find out why my beef is so delicious. She sort of put her head in her hands and went, oh my God, you are going to be here for 90 years. And I was like, why? And she said, because your beef is delicious because of the soil content, the plants that they’re eating, the place where they’re living, the breed that they are, the whatever. And eventually I came to the conclusion, I just had to accept it that it was all those things together make happy, delicious beef. And I think they did this in Australia. I wish they did it here. If you did it in the supermarket, it said this beef is delicious because. So rather than being red or whatever, you know, they kind of, people buy beef because it’s a certain colour or whatever. It’s nothing to do with that. It’s about, you know, the marbling and the aging and whatever. Anyway. But, uh, that’s what my passion was to, uh, you know, uh, get to the bottom of why it’s such an amazing thing.

Manda: And in the US again, Daniel Firth Griffith, he is allowed to shoot the cattle on the land and then prepare them there, and there’s no stress at all. And I kind of think we have somebody near here where the Slaighterman will come to the farm and will do it on farm. But then you’re not allowed to sell it. It has to be for home consumption, but I think there is a midway, we have one of the last very small abattoirs in the country, next village down, and you cannot take more than five beasts at a time. And, and you just literally walk them in and it’s as, it’s as low stress as it’s humanly possible to get. So you don’t have anything like that up near you?

Charlie: Yeah, we do, um, I don’t know if you’ve read the stats recently, but all those small abattoirs are disappearing for either due to red tape or, uh, generationally, people not taking one. And yeah, we had exactly that near us. And you’d take them in the night before and they’d bed them down in a, you know, very civilized stable. And by the time you left, they were chilled out, they were fed, and they went from a very, they went about five meters to where they, you know, sadly met their end. Um, but yeah, and the thoughts of them going in a clanking wagon to somewhere miles away where they’re herded by people who aren’t really bothered, but that is totally wrong. And you don’t, you don’t want to be really eating that stuff because that’s just –

Manda: It’s abuse.

Charlie: It’s morally wrong to eat that. It’s like eating farm salmon. If you eat farm salmon, then you should have a really strong think about that because that’s, that’s the worst industry on the planet.

Manda: We’ve got a no fish policy at home at all because the, the oceans are being fished dead. Even if it’s not from salmon, there’s nothing left.

Charlie: It’s not just that, it’s just you’re crawling an animal that would go thousands of miles and then, and because it’s a fish, people don’t really think about that fish, you know, get a bad rap. Because they’re not, again, like red squirrels –

Manda: Because they’re not cuddly. Unless it’s a, a whale. Anyway, and I know people, I said, unless it’s a whale, I know A whale is not fish. A whale is a mammal. It’s okay. I’m aware. Um, but let’s go back. So in an ideal world. If we could change the legislation, change the structure. Because I am already thinking I’m going to be inundated by emails from, from vegans going, we shouldn’t be eating meat at all. And I happen to think that’s wrong because I think we need to end industrial agriculture around the planet. It just has to stop. Part of the reasons the oceans are dying is industrial runoff of a runoff from industrial agriculture. So NPK, we’re right at the edge of the seventh of the nine planetary boundaries, which is ocean acidification, but we’re already over the nitrogen and the phosphate, and that is absolutely runoff from agriculture. And the glyphosate is destroying us all. And so we need to end industrial agriculture. I have, again, a friend who lives in a community and he wanted to be vegetarian. He went to this community, they grow all their own food and he discovered that he couldn’t do that. But he’s at a place where the slaughterman turns up and does it for them.

Charlie: Is industrial the right word? We still need to make food for how many billion of us there are, But we can do it in a, you do it in a way that’s sustainable. Right? So it’s, it’s still, if you like industrial, but it’s, then it is the word. It’s like wilding. The word wilding used to be a wonderful word. It’s now a dirty word in farming because it just basically means not farming. What I’m saying, what I mean is if you could, like I was talking you about, rather than using, uh, NPK if you were doing composting, for example, which you can do, right? So you can improve the soil without putting any manmade chemicals in it. And, uh, and, and actually you can, they used to be, they used to talk about how many harvests were left, was it 30 or 40? Now if you’re doing that, like Tom’s doing, and I’m

Manda: Yeah. You’re building soil.

Charlie: We’ve got as many harvest as we want because we’re looking after, going back to, the soil. You, you just have to farm on a big scale as we’re all going to die. Right?

Manda: Do you? Patrick Holden reckons that he’s got his organic farm, which is the longest standing organic dairy in Wales. And next door they’ve got vegetable farm and they kind of share the dong from his cows, goes onto the land for the vegetables. He reckons that I think 12 of those would feed the whole of Wales. We don’t need big farms. We need local farms that feed their community.

Charlie: I agree with that. Yeah.

Manda: And provided it’s done in a way that’s actually, I mean, because you’re not just increasing soil depth, you’re sequestering carbon, you’re increasing water uptake. You’re changing the nature of the soil such that the food that’s grown, that’s actually a nutritious instead of killing us. And I don’t see any way that we get that big scale ploughing and combining and all the rest of it’s going to feed enough people in a way that doesn’t kill us and the plant.

Charlie: I agree. I guess what I’m saying is that what I’m trying to do is to disrupt this in a way so that we can do this. So we, let’s, let’s move some of these words off the table and make it more positive. Let’s, let’s make this a bit more of a, an uplift. It’s like, I think, to be honest with you, a lot of climate change. The horse has bolted. Let’s deal with some of the stuff we’ve got here and make it as best as we can and then maybe we can do it that way rather than trying to, it’s not easy, you know, how, how to eat an elephant, you know, in 40, in 40 bites or, you know, but you know,

Manda: But there aren’t very many elephants. Let’s not eat elephants.

Charlie: Not elephants. Okay, big chocolate elephant, you know, do you know what I mean? What I’m saying is I’m very positive, I’m very optimistic, and I think we can farm in a way which is sustainable for all of us and for nature. So, as I’ve said to you, my common-sense farming is that the, the environment on my farm is as in important as growing the food. They’re both in the same thing. There’s not one over there and one over there. They’re both the same and they both feed off each other. So the hedges. A corridor, a place of wildlife, uh, you name it, a place where the plants can grow, et cetera, but they’re also providing shade for the cattle, right?

Manda: Yeah. And, and browsing and all the rest.

Charlie: So I think it is just to be, it’s just to be a bit more clever, and we can farm gently and sustainably on whether, you know, as you say, you might be right. We can bring the whole thing down in scale. So more things can be wild.

Manda: And what’s wrong with saying we need to get rid of industrial farming? Because I think we need to get rid of monocultures of farming.

Charlie: Farming in itself is an industry.

Manda: This is, I think this is quite interesting given the nature of this podcast is that we need total systemic change. We’re not going to go back to being forager hunters, which is who we were when we were really connected to the land. But every foraging hunting tribe managed the land, but they managed the land in a way that was. With the web of life. Now we know that, you know, Australia, the Americas, Africa, everywhere, where white people turned up and destroyed everything until they got there. The land was a managed thing. It just wasn’t managed in square patches where we said, we own this middle land and we’re going to control what’s on there. And I don’t think we can go back to huge scale farming at that level where we’re farming an entire continent, managing an entire continent. But we can go back to managing the land with the land, talking to the land. And I want to talk to you in a minute about your daymen’s, because I think you’re already talking to the land. You’ve got your wonderful person who makes your pond, who understands the land. And so we’re no longer fighting the land. We’re not, for me, industry is about human control and what we’re wanting to get to is partnership. Actual partnership with the land and feeding people. And I don’t think we get that. I don’t think it matters so much what you eat if you aren’t to be vegan. That’s absolutely anybody listening, I’m not suggesting you can’t be vegan, but don’t pretend it’s saving the planet because the monocultures of lentils may not be as appalling in terms of welfare to the actual animals. As industrial beef farming say, you know, the feedlots in the US are an absolute abomination, but 300 acres of lentils is 300 acres of sterile land on which everything that’s in there and under there is being destroyed. And it’s, it’s just because you don’t see the eyelashes doesn’t mean you’re not destroying the whole of an ecosystem. So get our food production back to being actually a partnership with the land, which is, I think what you’re doing.

Charlie: So if you said to me, Charlie, right? I tell you what, I want you to look after vegan people rather than carnivore people, right. I could do it. I could do it the same model.

Manda: Would you not need some inputs?

Charlie: I would, I would, it would make it harder. It would be really difficult, but I’d have to go into cycles of growing a lot of nitrogen growing. You know, you’d have to put a lot of clovers and a lot of things into the ground, would have to do five year cycles. But the other thing to be going on was, I’d still have the hedges. I’d still have the woods, I’d still have the ponds. I could, I could do it. You know? I think there’s always going to be a mixture of people on the planet. And you need to accommodate for them.

Manda: I’m not suggesting we don’t, but I think we need to all start eating. My feeling is that you need to eat from a place that you could walk to. If you’re in a city, then then eat. Clearly there has to be a ring around your city that is producing the food for the city, but we can produce all food in cities, but we need to stop the five continent just in time supply chain that says it’s okay to import your tomatoes from. Huge, huge factory farms in Spain where they’re just taking all of the water and you know, you eat a few tomatoes when they’re in season in the UK and, and then you get quite used to eating beetroot in the winter. Um, because you know, that’s one of the things, beetroot cabbage, we have to change the way that we’re eating everything. And because we have to change the nature of our relationship to the land that grows the food.

Charlie: Do you think? So you, you and I get, I get that completely. But if you are somebody who’s in a sort of socially disadvantaged situation where they can’t afford to put the plate on the table, they’re not really, I don’t think they’re really thinking about are the tomatoes and season.

Manda: Which is why we need this to change the system because the system is producing tomatoes have no nutritional value.

Charlie: Or chickens, chickens that are too quick. You know, it’s, it’s, it’s all wrong.

Manda: So let’s assume systemic change that gets rid of industrial farming because the industrial chicken farms are also Auschwitz for chickens. They’re utter hell, let’s not do that. And again, you maybe have a chicken once a month, but it’s an actual chicken that grew on an actual small holding and, and had a life and it’s not going to have been just 12 weeks old when it was had its night wrong. And it didn’t go through the absolute horror of chicken avatars, which are guys, you do not want to know what goes on in there. When I was a vet student, we had, we were supposed to do two weeks in, in an avatar and I lasted the first morning and went, I can’t do this. And the guy in charge went, no, everybody says that. Every single vet student who’s been through here has got to the end of the first morning and said, I can’t do this. And I was vegetarian for the next 20 years for exactly until I was living somewhere where we could, I can work with things that have. And the cattle and the sheep that are on the land, and I can walk to the place where they go to be. I have no problem with things dying as long as they’ve had a good life and a decent death.

Charlie: They all have personalities, don’t they? My aunt had a chicken that used to live with her, and, um, chickens, like any female animal, have a point where they stop laying eggs. And the chicken, I want to call it Belinda, and I think it was called Belinda. And Belinda, if you went to my round, to my aunt’s house, she had two deck chairs, one for her and one for Belinda. So Belinda would sit on the thing and fall over backwards and lie there with her arms in the, her feet in the air, or she’d be asleep by the aga or whatever. And when, when my aunt died at the age of 92, about two years ago, had a funeral in the garden, in a tent, in the, the, the, the pride of, uh, place was for Belinda, the chicken who was wandering around eating the crumbs off people’s plates.

Manda: And somebody adopted Belinda?

Charlie: Yeah. So yeah, so there are two guys that lived at the end of the garden and that she went through a process of going to stay with them for a couple of days and coming home again until she was assimilated. And so she’s now. Living with those guys. But, um, so the point is these, all these animals have spirits and souls, and again, I’m not religious, but people who say animals don’t go to heaven. There’s something really wrong with that because I think actually animals are better than us. Um, they do it all without complaining. And, um, yeah, so you are messing with on a massive scale with things which, which are, you know, they’re alive, living creatures that need to be respected.

Manda: Yeah. And my indigenous friends who are still living at the edges of forage hunter communities say the reason that our culture is as sick as it is, is because of the way that we’d relate to the food that we eat.

Charlie: I talk a lot about, um, my stories about, uh, Philip Pullman wrote a book called The Dark Materials. And in that’s a wonderful idea, which you have to think of it, I call it demon, but he may be a Damon. It’s spelled D-A-E-M-O-N, and it’s a spirit animal that you have, which is the opposite sex to you. It changes all the time till you go through puberty and then it fixes, and it is your alter ego. So it’ll be your moral compass. It’ll tell you what to do and what not to do. But I think it really does exist if you sit quietly – uh, it’s really rainy, hard outside. Sorry if that noise comes through.

Manda: You have rain. I have rain envy Charlie.

Charlie: I want to go take my clothes off and run around it. But, uh, but um, anyway, yeah. So if you sit quietly by wood and the sun’s coming down and you just sit and relax and breathe, and breathe in and breathe out, you’ll then feel weird. You’ll have a strange feeling and you’ll actually becoming part of nature rather than you observing nature. And the weird thing about that is nature knows that too. So if you are a deer, you might have come around the corner and go human runaway. When you are in that kind of zone, the deer won’t, it’ll just walk by or a bird will land or whatever. And that is your, if you like, your soul coming out of your body or your spirit animal coming out of your body. So we have all these connections and what that does is. It totally relaxes you. It brings you down to a very calm place, and we have lost that ability. It’s still there in all of us. It’s innate, but you have to learn it or even maybe even be taught it. But yeah, I think those people are right. If you lose that connection and you think about it, we’ve got two eyes, two ears and a nose. These are all for being outside. That’s the whole reason we have this physiognomy. Anyway, but that’s why you like that.

Manda: Yeah, totally. And I, and what I find really gorgeous about this, because you wrote about it, we haven’t talked about your books yet, we need to talk about that in a moment. But, um, it feels as if you… I’ve been teaching contemporary shamanic practice for over 20 years now and practicing it for 20 years before that. And we had a lot of, there was, there was a little window in the late eighties, early nineties where a lot of indigenous people came across and gave very freely of their teaching in order that we learned to reconnect with the gods and the guides and spirits of this land. Not that we had to take on their lineages particularly, but that we recreated the broken lineages that were destroyed over 2000 years of history. And we teach people how to connect with guides that will then guide them. And it’s not always a first hit thing. You can meet a lot of guys that don’t. You meet a lot of things that turn out not to be good guides, but in the end you find something that you would trust with your sanity and your life. And you’ve evolved that just on your own in the forum naturally without, I don’t think you’ve ever read a single shamanic text, as far as I can tell. You never talk about it.

Charlie: What’s really interesting, what’s really interesting is I have a lot of people come around the farm and sometimes I just know I just, I’m getting a shiver down my spine now. I just know they get it when they land on the place. And yet it’s like meeting a fellow traveller. I don’t, we don’t have to have the conversation. We basically just go around and talk about it. But I know when they’ve left that you can just see that physically they’re much holier than they were when they arrived. And I think that can, I tried to do this with my local doctor surgery. I said, we can do green prescriptions, just bring people out. And I’m, I’m not saying I’m serious mental.. Well, I am actually. Gosh, I am. Doesn’t matter how bad your mental health problem is, it being outside in nature will help you to get better. It might

Manda: It might not cure it because if your problem is that you’re living in a society that is trying to destroy you, it’s, it’s hard, but it, you’ll have a bit of a sense of heart connection, so, yeah.

Charlie: Yeah. And I think they, what I had to learn was that the, a lot of people are scared of other people basically. And so you have to build trust with these guys. And even as I say, I don’t talk to them about their problems, I’m just walking with them. But they, they need to feel that connection with me. But I think, as you say, if you feel this, people intuitively know that, and I’m, know that I get it, if you know what I mean. Um, without actually saying, I’ve never read a shamanic test text in my life. Um,

Manda: But you have, uh, an animal that is particular to you. Are you able to share what it is?

Charlie: Yeah, I’ve written articles. I’ve got three, I think, um, otters, uh, I just think are most incredible creatures. And I name my business, my recruit business after that because they’re, they’re friendly, tenacious hunters.

Manda: I’ll tell you a story about that in a minute. Go on. Right.

Charlie: I’ve got a sense that swallows, they talk to each other all the time. If you hear them sort of, and they talk all the time, and then when they’re flying across the field, it’s sort of daisy hide you. The noise they make is almost just pure joy. They are just loving being in the moment. And I think my other one is, is, is roe deer; they are, they again, they’re not like Red Deer, they don’t herd. They do herd at certain times of the year, but they’re basically walking through the countryside and they’re browsing all the time and they’re doing it without any disturbance or, or whatever. And they’re, again, they’re quite ghostly and they are, you know, there are a lot of them. They can be a problem, but as an animal, oh my God, I think they’re fantastic creatures. What about you?

Manda: I’ll tell you in a minute, but let me tell you about otters. First of all, I remember because when I was doing the research for the Boudica books, which is late nineties, I went down to the British Museum and I was speaking to the guy who curated the pre Roman. They called it the late pre Roman iron age. It’s like defining a woman by her husband’s profession. It just made me so cross. But anyway, he curated that exhibition and he had done his PhD on the midden remains of the Eceni, which is the tribe that arose in East Anglia. And he said the really interesting thing was what you didn’t find, or they threw away. They didn’t find a single magpie, bit of a magpie. They found crows because crows are carrion birds that feast on the dead. And they, they’re linked to that transition from life to death. They found lots of white water birds because they can go from the gods to the water. But a magpie is black and white. And they’re either so taboo or so sacred that they didn’t have them. The other thing they –

Charlie: Thundering. It’s thundering.

Manda: oh, is it you lucky man? Gosh, I have total rain envy. Um, the other thing they didn’t find was not a single Otter pelt, and he said, again, they think otters were so sacred too. If your gods live in the water, which we think that a lot of them did, because a lot of the gold offerings were given to the water that you have this land mammal, which a apparently can breathe underwater because, you know, you’re just watching it, it goes down and it spends a lot of time down there. Beavers were not as sacred. You found lots of beaver belts, but otters were, were so sacred that they, you found, they did, they were not used for decoration or anything that might end up in the, in the range of the middens, which I thought was really interesting.

Charlie: I think the other magical creature, possibly even more magical is a hare.

Manda: Yes, yes, absolutely.

Charlie: I’ve had two or three experiences where I’ve been eyeballed by a hair.

Manda: Gosh.

Charlie: The only other animal I can look at it to is a dolphin. So I went swimming with dolphins in a place called Kaira in New Zealand. And it’s a very strange experience because dolphins look straight at you and they look into you. And the other interesting about dolphins is they click into you as well. So they’re looking inside your body. Hares aren’t doing that, but what they are doing is they’re looking into your soul and they, they are just extraordinary animals. I think probably the most extraordinary there are.

Manda: They and totally sacred to all of the old gods. And loads of history in Scotland, which is where I grew up. So probably in England too, but I only know from Scotland of the, of the old mythologies of hares turning into witches. Basically were, were hares and yeah, totally. I wrote the books because my lurchers at the time, which for those outside the UK, that’s a cross between a running dog and a herding dog. My American editors, for reasons I’d never understood, used to think that a lurcher was a homeless man. Because my bio used to say Manda lives in Suffolk with two lurchers and too many cats. And I thought that was quite amusing until I discovered that they completely didn’t know what a lurcher was

Charlie: It’s a good name. I get that I get where he is coming from. I understand that.

Manda: Kind of weird. Um, but she caught a hare and that led directly to me going, doing the vision quest because it shouldn’t happen.

Charlie: What I, when I wrote about hares, I found a carving in a church. I think it was an of a hare chasing a dog and the reason was because that’s what they thought it should be the other way around. You see what I mean? So it’s normally the other way around, isn’t it?

Manda: Yeah. And but have you lost your dog? Certainly. Where I used to live, it was because the hares had lured it away. It was, you know, they were really amazingly magical things.