#221 End State: 9 Ways Society is Broken and How we Fix it, with James Plunkett

This week, I spoke with James Plunkett, a man who has spent his career at the intersection of policy and social change. From the halls of Number Ten to the charity sector’s front lines, James’s unique perspective has birthed a book that critically examines what’s wrong with our society and offers tangible fixes. Together, we dissect our societal challenges, from outdated institutions to the technology of gods, and discuss structured ways to mend a fractured system.

James has spent his entire career thinking laterally about the complicated relationships between individuals and the state, with a particular focus on digital transformation and public policy, from the social innovation agency Nesta to the charity Citizens Advice and before that roles at 10 Downing Street, the Cabinet Office, and the Resolution Foundation think tank.

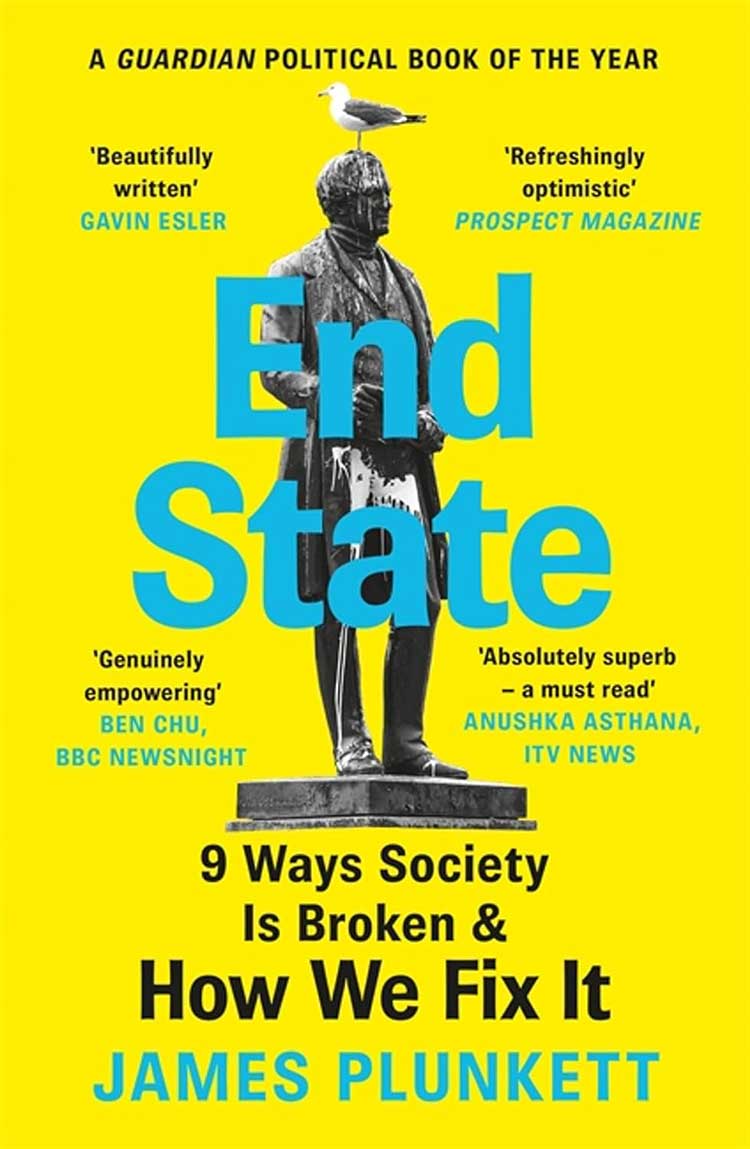

James combines a deep understanding of social issues with an appreciation of how change is playing out not in the ivory tower, but in the reality of people’s lives. As a result of all these insights, he’s written an optimistic book, End State: 9 Ways Society is Broken and How we fix it. that explores how we can reform the state to meet the challenges of the twenty-first century.

As you’ll hear, he didn’t think of this as a hopeful book when he began – it was more of a response to seeing the ways the old system of the 20th century was not keeping up with the new world. How we have, in EO WIlson’s words, ‘Paleolithic emotions, Mediaeval Institutions and the Technology of gods’ and this isn’t necessarily a good combination to face the meta-crisis. But James did come out with hope for the future and structured ways our current system could make these happen. Accidental Gods often inhabits a world where the current system is broken beyond repair and the only answer is to create a new one and help people shift into it. So this was fascinating, enlivening conversation with someone who has lived and worked in the heart of the superorganism and can see ways through to a world where the human and more than human worlds flourish.

Episode #221

Links

In Conversation

Manda: Hey people, welcome to Accidental Gods. To the podcast where we still believe that another world is possible and that if we all work together there is time to create a future that we would be proud to leave to the generations that come after us. I’m Manda Scott, your guide and fellow traveller on this journey into possibility. And this week’s guest is someone I’ve been wanting to talk to for a long time. James Plunkett was a policy advisor to Gordon Brown, the Prime Minister, in the halcyon days of the last Labour government in the UK. In fact, he has spent his entire career thinking laterally about the complicated relationships between individuals and the state. First in number ten and then as a leading economic researcher and writer, and then in the charity sector, helping people who are struggling at the front line of the economic change that we’re seeing. James combines a deep understanding of social issues with an appreciation of how change is playing out, not in the ivory tower or the halls of power, but in the reality of people’s lives. As a result of all of this, he’s written a book called End State; Nine Ways Society is Broken and How We Fix It.

Manda: And as you’ll hear, he didn’t think of this as a hopeful book when he began. It was more of a response to seeing the ways the old system of the 20th century was not keeping up with the new world. How we have, in E.O. Wilson’s words, Palaeolithic emotions, medieval institutions and the technology of Gods and this isn’t necessarily a good combination with which to face the meta crisis. But James did find hope in the process of writing the book; structured ways in which our current system could make a better world. Accidental Gods so often inhabits a world where the current system is deemed to be broken beyond repair, and the only answer is to create a new one and help people shift into it, so it was really interesting to speak with someone who has lived and worked in the heart of the superorganism and can see ways through to a world where the human and more than human worlds flourish. So here we go, sharing the conversation. People of the podcast, please welcome James Plunkett, author of End State.

Manda: James, welcome to the Accidental Gods podcast.

James: Thank you for having me.

Manda: How are you and where are you this morning?

James: I’m very good this morning. I’m in London in Blackfriars. So I can actually see if I look over my shoulder a view of the Thames, which is rather lovely. Yeah.

Manda: Wow. How far is that from the Houses of Parliament? My knowledge of London geography is basically nil.

James: Oh, close, close, scarily close. About a ten minute walk down the river. So, um. Yeah.

Manda: Okay. Gosh. And before we get into all of the exciting high politics and deep change of the system, the key question that I have written on my notes is, what kind of dog do you have? Which is obviously the most important thing because you mentioned this big hairy dog and I’m thinking it might be a lurcher.

James: I do. He’s a poodle. He’s a standard poodle.

Manda: Oh, nice. Standard poodle hasn’t been on my list of potential puppies, but maybe I should put it there. What’s it like living with the standard poodle? We’ll talk politics in a minute, but dogs are more important.

James: They’re wonderful. I recommend poodles. So obviously they’re hypoallergenic, which is the reason lots of people get them. They don’t shed hair everywhere. And they sort of stay puppy like in mentality, but they’re quiet, this is the thing I like. They’re not yappy. They’re sort of lively but quiet, which is a nice combination.

Manda: Especially the standard ones.

James: Yeah. Then standard ones are big, right? Yeah.

Manda: Beautiful. I knew a woman once who had a standard poodle called Seiko, and she was epileptic. And Seiko could tell when she was going to have a fit and wouldn’t let her go out of the house. They are super, super bright.

James: Empathetic. Yeah. They can tell when you’re down or when you’re feeling happy, they reflect your emotions.

Manda: Right. Gosh. All right. Moving away from dogs. You have written a book called End State; Nine Ways Society Is Broken and How We Fix It, which is exactly what the podcast is about. And you are one of the few people I’ve come across who’s been deep, deep in the heart of our current governance system and has stepped back and said, guys, it’s not working. We need to change it. And so what I really want to get to in the next hour is how best we make the changes. But very briefly, just talk us through how you came to see that things were broken and how it led you to write a book. Because writing a book is hard and a lot of work. What drew you into it and why did you do it?

James: So the moment when I look back, the sort of moment the seed of the book came to me, was in those systems you describe actually. I was working at the time in number ten in the late days of the Gordon Brown government in the UK, so late 2000. And I remember very clearly this slightly peculiar meeting that I was called into, as you often are in number ten at the last minute, not quite knowing why I was there. And it was a meeting between Gordon Brown and and Tim Berners-Lee, who is the man often credited with having invented the internet, if such a thing can have been done by one person. But it was a slightly strange meeting and we sat in the garden of number ten, and it was a nice spring day. I remember this image very clearly of Brown sitting on my left and Tim Berners-Lee sitting on my right. And the thing that struck me about the meeting as I heard the conversation play out, was these two men speaking almost a different language to each other. Gordon Brown was kind of the image of 20th century government, if you like. He asked questions like, what levers can we pull, Tim? I think at one point he said, how do we beat the Americans on this agenda? Talking about technology and how governments kind of grapple with technology.

Manda: That played out well, eh?

James: Yeah. And Tim Berners-Lee, people who have seen him speak, he speaks very fast. And he speaks in this completely different language of, he was talking about platforms, about networks, about iteration, about optimisation, about big data. And I felt this kind of sense of unease watching this conversation play out. I realised afterwards I think it was this sense of a sort of disconnect between, if you like, the sort of machinery of government, this kind of mechanical idea of Whitehall and the machinery and the levers of the 20th century state, and what was then still very sort of emerging digital economy and the economy of the internet and of platforms and of big data. And now we know of of artificial intelligence. And I think I felt uneasy because the mismatch, they were speaking different languages and they seemed to me to come from different eras. And it left me with this very sort of slightly queasy sense that government was being left behind. Our institutions were being left behind by this new economy, new society that was emerging. So that was the unease that kind of then got me to embark on the book.

Manda: Right. And they are men of a similar age, I’m guessing. Tim Berners-Lee has got to be a contemporary of Gordon Brown’s and yet he’d been in an environment where his brain, I’m guessing, is wired slightly differently. We can’t prove that kind of thing, but it seems to me there is a 21st century fluidity of thinking, and there’s a 20th century status of thinking.

James: I think that’s right. And I think one thing that happens at times like these, and maybe we can come on to talk about times before when we’ve been through similar challenges, that the new thing emerges alongside the old thing. And so clearly there’s not a sort of neat transition. So you get in the same society, in economy, people who think in the new way alongside those who don’t. Organisations that function in the new way, alongside those that don’t. And all of it lives side by side for this kind of period lasting many decades. And it leads to this slight sense of sort of messiness, I think, that characterises what it feels like to live in the 2020s as we do now.

Manda: So let’s have a look at the times when you have seen this play out before, or at least the times when you have read about it playing out before, because that was one of the reasons for hope in your book, is this isn’t as novel a situation as it can sometimes feel. So where are the parallels? What are they with, and how do you see the current state of affairs mapping on to states of affairs that have happened before?

James: Yeah, I didn’t set out to write an optimistic book. Because it started from that sense of unease of government being left behind and it became optimistic in the course of the research, really. I remember there was a particular kind of telling moment, when I was living in the US at the time, and I was back for Christmas and in London, and I went into one of those wonderful second hand book shops on the Charing Cross Road and just was browsing, and I found a book on the shelf that I plucked off the shelf, which was a collection of newspaper articles, letters, diary entries from the Industrial Revolution from around 1850 to 1870 or so. Just an edited collection. And I did that thing where you start reading a book, and then you keep reading, and then you take your bag off your shoulder and sit down. And it got dark outside. And I eventually bought the book but it was a sense almost of the hair standing up on the back of your neck, that the tone of these letters and newspaper articles from that period, it felt so familiar. Because at the height of the Industrial Revolution as was then sweeping across Britain, there was a very similar sense of a new type of economy in society emerging, our governing institutions being completely unfit to cope with what at that time were problems like child labour, sewage piling up in the streets of London and in cities around the world.

James: Problems like the railways being entirely unregulated. There were no roofs on the trains at the time. So even worse than we think of now as the railways, the experience we have. And people felt this similar vibe that things were spinning out of control, they were losing their grip on the situation, and their governing institutions were being left behind by this new economy at the time, an industrial economy. So oddly, that gave me a sense of hope, because of course we sort of got through that set of challenges. We built a new set of institutions to cope with many of those perils of things like sewage in the streets of London. So the question was can we do that again? Could we repeat that feat of rebuilding institutions for a new technological era? So it left me feeling we’d been here before.

Manda: And I would like to unpick that a bit more deeply. But just before we do, there’s a wonderful quote that really stuck out for me. This was a letter to The Times, and it was about sewage in the rivers, as far as I can tell. And it said, ‘I beg most emphatically to protest against being poisoned, and I beg further to ask those whose business it is, and who are highly paid to see that I am not poisoned, why it is that I am being poisoned’. And I thought, first of all, letters to The Times are not written with that level of clarity these days. But also it’s exactly the same question all my friends in the please can we clean up the rivers movement are asking, is there are people who are being highly paid to keep these rivers clean and they are failing across the board. And in fact, it appears to be that they are failing deliberately. So it struck me we have been exactly here before, and yet we haven’t been in the technological singularity before. Technology was ramping up, but it wasn’t ramping up on basically a vertical curve. And we haven’t been at the biophysical end stage that we are now. And we had time for decades of old white men to argue with each other about whether children should be employed in factories or not. And we haven’t got that level of time now. What kind of time scales do you think it would take to transform our current polity, and how long do you think we’ve actually got? Because that seems to me, I think your book is lovely and I would like to be able to hope, but I look back and I look forward and and it seems to me we’re screaming towards the edge of a cliff rather faster than we were. But it may be that my perspective is just that I’m too caught up in it. Where do you see things?

James: Yeah, I think it’s definitely right that it took it took a shocking amount of time for some of these what now seem to be obvious common sense ideas to emerge. You know, one of the stories I tell in the book that I became very interested in was railway mania, which swept Britain in the 1840s, when railways were being built for the first time. This huge rush of investment and frenzy of investment, and we had no regulation of the railways, because there had been no railways of course, it was an entirely new industry and technology. And one of the ideas that emerged, you know, one of the problems at that time was there was no standard gauge for railways. And so there were these two competing ideas about how far apart you should lay the tracks. And the two great engineers, Brunel and Stephenson, had different views on this question. And so they’d built two railway networks essentially across Britain. And at every point that they met, they didn’t join up and you had to stop one train, everyone got off, unload everything, and get onto another train at a different gauge to work on the other tracks. And, you know, in that case, the idea that emerged that was initially radical was that we should regulate a single standard railway gauge.

James: And of course, that’s now completely common sense. Of course, you should have a standardised gauge and indeed a whole wider system of regulation for railways and other technologies. But I raise it as an example, because it took 60 years for what were known as the gauge wars to play out, and eventually for us to both legislate and then actually implement and enforce a single gauge for railways. And something not dissimilar happened with Child labour, very clearly one of the great moral issues of the time. And again, it took many, many decades for that to be both banned and also for the ban to actually be enforced. So, you know, the lesson from last time certainly is it takes us 40, 50, 60 years in those examples, to get from something seeming a very obvious problem to having a sort of solution in place. And I think you’re right. I mean, do we have that long now with climate change? Very clearly we don’t. And we know that by 2050, if not much sooner than that, we have to get to a radically different economy. So I do think that’s a worry. Can we move at the pace we need to?

Manda: And do the people currently holding the reins of power acknowledge that we need to move at all? Because reading your book was one of the things that struck me, was the extent to which the people who wanted to preserve the status quo had a system that was designed to preserve the status quo. Even you were talking about increasing the franchise to women, particularly. And I am thinking that we need to increase the franchise age wise. We need massively to reduce the lower age limit, if we’re going to get a voting system that brings in people who have the visions to make change. And yet I can imagine it could easily take decades to bring that in, absent some kind of big disruptive force. And you mentioned franchise in your book, or changing the voting system in in some ways. If we drill down into that, I have a number of questions. First of all, what would you do now? Because what you wrote a couple of years ago might not be what you would do now. And second, how is that being received by the people that you used to work amongst? The people who are where they are now because of the existing voting system.

James: I think it’s key. In the book, one of the repeated patterns that played out in the 19th century was this gradual expansion of the franchise to solve the problem that the people who were suffering from these great problems of the age didn’t have the power to address them. And that obviously then became one of the kind of mechanisms by which change played out, that people got that power through the vote. And it’s fascinating to think the people, as you rightly sort of imply, the people who are paying the price on climate change, are next generations; both children today and also unborn generations. Probably the most radical idea I explore in the whole book is essentially how do we enfranchise children? There’s this idea that emerged partly in Japan, interestingly, one of the oldest societies in the world has a profound challenge of an ageing electorate, and it’s causing huge problems in Japan. And the idea is could you give children some kind of weight in the system by giving parents an additional vote to cast on behalf of their young children, and then when their children become perhaps 14, perhaps 16, old enough to cast their own decisions, then, as you say, lower the voting age. And I have to say, that idea is not in public discourse in the UK, certainly, and in the US, even though we have a similar challenge with an ageing electorate.

James: But it’s been fascinating, since I wrote the book, the entire climate movement led by children, for example, and Greta Thunberg and school strikes and other mechanisms like that, has happened since I wrote the book. And I do think that’s the kind of thing you would expect to play out if there were to be this push, to say you cannot discount the votes of such a significant portion of the population. And we’ve seen, I guess, within more centrist discourse, ideas like commissioners for the future. So in Wales, for example, there’s this idea that the government has pursued, of having a person whose responsibility it is to think about the impact of decisions on future generations. There’s a movement for what is sometimes called The Seven Generations, which is to think seven generations in advance and to think what did seven generations before us, what kind of problems and also kind of assets did they leave us, um, as our ancestors? So I don’t think we’re going to get votes for children any time soon, but I do think that the discourse is moving in that direction, of recognising the importance of future generations.

Manda: Let’s unpack that a little bit more, partly because I’ve just finished a book in which getting votes for kids was a central part of the plot. Yay! However, I also was just talking last week, and it’ll go out before this, to Alex Lockwood of the Humanity Project, which is looking at how can we shift our electoral system. And he had an idea which was that people are born with, say, a hundred votes and you lose one every year. And so it gives a proportional weighting to younger people. And then if you then also reduce the voting age. So the voting age for UK Parliament, the minimum is 18. In Scotland and Wales for the devolved parliaments it’s 16. And I didn’t know that until I started writing the book. How how do we get to that? How is it that you’re okay to vote for a Scottish or Welsh parliamentary system, whatever we call it, but you have to wait another two years in England. And it seems to me, I speak as a former actually probably still Corbynista. I joined the Labour Party when he was elected, I left the day Starmer got in. So I have a particular viewpoint. But if people under the age of 60 had been the only franchise, 18 to 60, in the ’17 and ’19 elections, Corbyn would have had a landslide. And we are where we are because old people have a particular way of looking at the world, that is not I would say, fit for the 21st century. And we’re going over the edge of a cliff that could potentially see us and the rest of the biosphere verging on extinction, which is quite serious. Slightly more serious than do we send kids up chimneys or not, although I’m very glad we don’t send kids up chimneys. Is there genuinely no move within the current power nexus, whatever we call it, I call it the Death Cult, but that’s probably not a fair thing. Nate Hagens calls it the superorganism, which is probably nicer. Is there no move to give younger people any kind of say in who’s elected to wield power?

James: I think it is interesting, though, if you look at the climate movement, for example. If you like, the two most activist populations in climate politics are the young and the old. And it’s very interesting, if anything the missing segment, certainly if you look at the more activist end of climate politics, are working age people.

Manda: But that’s because they’re working age, isn’t it? I mean, my partner has kids who are in their 30s and 40s, and they would love to be activists, but they have young children and jobs. And if breathing wasn’t a multitasking option, they wouldn’t have time to breathe. They definitely don’t have time. I was with XR in the October Rebellion, and there were people who had brought their kids, who were I thought incredibly brave. But most people, you’d lose your job if you were out in the streets every Friday.

James: Yeah. I think it’s difficult with intergenerational politics. You get into a sort of, it can become zero sum. And I’m not sure that’s that helpful. And I do think there’s questions about alliances across the generations that are interesting. They’re quite fruitful. And personally the arguments I was most interested in the book exploring were certainly not about disenfranchising older populations, so much as about enfranchising younger people. Obviously there’s also just the gradient in voting turnout, you know, younger people are less likely to turn out to vote in the first place. And so that compounds everything we’re talking about. But certainly I’m not sure it’s a challenge we can ignore, that if you project the lines forwards in terms of ageing demographics and voter turnout, you get relatively quickly, certainly in Japan and older societies like Germany, to a society where the median voter is nearing retirement. And that’s a very challenging situation, not just environmentally but even fiscally, where you see countries spending much more proportionally on pensions than they used to. Much more proportionally on services for elderly people compared to child care, for example. So even if you just think about things like how do we balance the books, how do we invest money wisely? I think you you have to think about these questions of demographics.

Manda: So what do we do then? Let’s expand a little bit beyond age, because we could probably spend the entire hour discussing that, and that would be pointless because you have a lot of other ideas. Let’s run through. If we had an election tomorrow and there was a hung parliament and everybody got together to say, look, the world is in crisis. We’re going to put aside our tribal differences, and we’re going to see how we can bring wisdom to power and power to wisdom. So wisdom to those with power and power to those with wisdom, which strikes me as the bottom line that we need to do. And you don’t say it explicitly in the book, but it seems to me that that’s what you’re aiming for. What would you do if they said, right, James, come in. You’re our senior advisor now. You’re here to look at the existing system and see how can it be made fit for purpose, in the 2020s and taking us forward as far as we can. We want resilience. We want flexibility, and we want to represent the needs of the people within the framework of a living planet that we cannot afford to destroy. What would you do?

James: So the way I started to think about this, since writing the book is in terms of choices and capabilities. I find this interesting. So on choices, when you look back on why did we make the progress that we made over, say, the 150 years from 1870 onwards, a remarkable period of progress. So life expectancy doubled, if not trebled in pretty much all regions of the world in that period. Real incomes rose sixfold in that period. And quite a large amount of that progress is down to some really significant, bold choices that we made about the kind of future we wanted to build together. And those choices now we would name as things like founding the NHS in Britain, for example. Founding Social Security, to give working people more security so that if you were sick, you wouldn’t be cast immediately into abject poverty, that you would have a system behind you. National insurance and so on. Economic regulation, big choices we made together. And I think one reflection is where in politics today are we talking about the big, bold choices that we might make, about the kind of future we would like to see by, say, 2050? And it’s hard to escape the feeling, I think, that our politics has become sort of smaller, more incrementalist. We have these quite vehement arguments about tweaks to parameter values, if you like, within the current system.

Manda: Yeah.

James: And Keynes was very interesting on this actually. There’s a lovely quote from Keynes, which I’ll get wrong, but which was something to the effect of if you’re talking about building a better future, you have to start from the future you’re trying to build and work back from there. Rather than sort of start from the accounting of now and how much money have you got free today. And that’s how we did things like build the NHS. We didn’t say can we afford this today? Is there a spare several billion pounds in the Exchequer? We said we would like to build a national health service and we worked back to what would make that possible. And this is why in the book I explore some big and admittedly bold ideas, like the four day week, for example. Like even a universal basic income. Which is not to say those ideas are doable tomorrow, but they’re the kinds of ideas it seems to me we need to be talking about. And that tick this box of ideas that might describe the kind of society we might like to build together by, say, 2050. Some sort of distant but not that far off future date.

James: And then the second word I think is really important is capabilities. Because the other thing that strikes me we’ve done over time is we’ve increased our capacity to do things together, to act collectively to solve problems. And this is where it gets sort of into the plumbing of how we work together to make our society better. And I think, you know, reflecting on why have we lost hope, why have we sort of lost our ability to imagine a better world? That’s partly because we no longer believe in our capacity to do things or to make things better together. And in the past we didn’t just make choices, we built systems that then delivered on those choices, like the NHS. It’s a system, it’s an institution, it’s an organisation, a set of capabilities. And I do think we’re lacking certain institutions, capabilities, organisations, call them what you want. To do things like solve the climate crisis, the mental health crisis, the crisis of loneliness. And there’ll be different to the kinds of capabilities we built in the last 100 years. So I often talk about it in those two terms. We have to make some big, bold choices that will seem currently radical and will become tomorrow’s common sense. And we need to build some new types of capability to do different things and better things together, than we are frankly able to do, if you look at the world right now.

Manda: Yes. And you wrote this in the book. This is my favourite quote from the book, where you said, ‘or perhaps radical leaders will emerge, courageous visionaries who will pursue reform regardless of the political heat, because it’s the right thing to do’. And I would say we urgently need those. So if we were to make choices and look at the capabilities of what we’ve got, I live in a modern monetary theorist world, so money is not a limitation. Governments spend money into existence and then it flows around the system and comes back and they take it out of existence. If we were to not worry about the funding, and you’re still James Plunkett, senior adviser to a coalition government that is basically doing its absolute utmost to get things right, which I struggle to imagine, but let’s stay with the fantasy for a moment. What choices and capabilities would you ask for? First of all, what does the society that you would like look like in 2050? If we get there, we paint our picture. We’ve woken up in the morning and it’s the beginning of February in 2050. What does our world look and feel like?

James: Yeah. So towards the end of the book I try to almost imagine my way into how would government function, for example. What would it feel like to walk around government in say 2050? And what kind of institutions might we have built? And I think it’s a genuinely hard question to answer, because if you’d asked someone, say, in 1910, to imagine the NHS, people genuinely would have struggled to imagine something of that scale and complexity. Just the sheer administrative complexity of diagnosing disease at scale in that level of reliability across the population. And so it is a leap of imagination, actually. And I try to get into it a bit in the book. I think things like, I think some of our language would change. So I’m struck when we talk about government today, we talk about The Government, The State, and we still talk largely in these mechanical metaphors, which I think are metaphors of the last century, not of this one. And so we think about big government departments, big hierarchical departments that pull levers and do things to us and that were powerful in solving lots of the problems of the 20th century, like communicable diseases, for example, and building the NHS and so on.

James: My gut is that if you were to describe the kind of institutions and government we would have by 2050, you would be talking more in verbs and nouns, for example. So you’d be talking about things like, how do we care together? How do we decide together? How do we build things together? You’d be talking more in terms of services, I think, than we do today. And you wouldn’t talk in terms of a government that does stuff to us, you’d be talking about how do we do things together with each other. So it would be more enabling if you like, there would be a sort of an infrastructure through which we make choices and care for each other together. And that sounds fluffy, it’s quite hard to pin down, but I think it’s not impossible.

Manda: I don’t think it does at all. I think it sounds really good.

James: I think it sounds exciting. And there are folk who are talking about things like how do you build relational public services, for example. So that when people have mental health challenges or indeed are suffering from chronic physical conditions, like chronic pain and so on, our solution isn’t to say we will prescribe you these medicines and meet you 1 to 1 in a 15 minute GP appointment, but might be to do things like, say, connect you with other people who have similar conditions in your community, so that you can build meaningful relationships with those people and talk together about how you each go about your lives, managing your conditions and living joyfully with those conditions and living a fulfilling and flourishing life with those conditions. And I think it’s not impossible to imagine institutions, maybe many of them digital, for example, that connect us together with with each other, to do things like improve our mental health, our wellbeing, our physical health, and to manage and live and thrive and live joyfully with chronic conditions. So that’s sort of one example. And that would be very different from the sort of hierarchies, the prescriptions, the sort of medical mental model of, for example, an institution like the NHS, which has served us very well in dealing with more acute health problems. So, yeah, I think you can imagine that kind of repeating across if you like, our different public institutions.

Manda: So what’s the value system underpinning it? At the moment we have a superorganism or indeed a death cult, which is focussed on profit above everything else. Our our economy is designed to grow regardless of the impact on people and planet. And I would stay and I’m stealing this straight from Kate Raworth, that we need an economy that is designed to support people and planet, regardless of whether it grows. I thought that was pretty non-contentious, but I said it in a meeting with our local Tory MP, who’d said he would not come on a platform if we were going to discuss political aspects. And I said, surely this is not political. And he went, no, that’s absolutely political. So it’s not just the economy, but the whole of our superorganism is oriented at the moment towards economic growth, because that’s the end goal that we’ve given it. If we’re going to get it to change direction, it seems to me we need to give it different goals. If we’re going to a verb led system, which sounded to me a really good idea, what for you would be the underlying values that would give the superorganism a new orientation?

James: So I think some of the words I’ve started to use, and I think the language is one of the most interesting parts of this, because one of the things that is, if you like, redundant or outmoded is, is the language, the words that we reach for. The language itself starts to fail us. And I think that’s a key aspect of why the systems become outdated. I’ve started to reach for words like ‘integrated’, I think is a powerful word. I think you would not describe our 20th century institutions as being integrated in the sense of thinking about the systems within which we need to live; ecosystems, for example, social systems and so on. And I think integrated is an important goal. One thing I often talk about these days in terms of the kinds of skills and capabilities you might want in a future government, is to draw more broadly on the richness of insight you would get from a range of different disciplines, for example. So, you know, it’s very clear our 20th century government was very narrowly reliant on economics as a discipline.

Manda: And neoliberal economics, particularly.

James: A certain subset of economics, which actually didn’t even make rich use of economics, which is itself a very rich discipline, of moral economics and political economy and so on. And so we drew quite narrowly on economics and then spread it across a very broad domain of our lives, arguably overly so, and didn’t make use even of the richness of economics, but certainly of other disciplines like sociology, psychology, philosophy, ethics. Design, for example, I think is coming to the fore in much of contemporary government debate. And so I think you would have a richer set of ways of understanding the world, a richer toolkit or a range of tools, to use to what we would describe now as making policy, I guess, and to make the world better. And so it would be sort of broader, more holistic, more integrated. And the other word I’ve started to use more of is human, which is a simple word, but an important one. I think that speaks to the fact that many of the systems we’ve built, even if we think there are good intentions sometimes behind them, have become inhumane in the way they interact with people.

James: The most emblematic example is, I think, the modern welfare system. We’re in the very strange situation where the welfare system is there to provide people security, and indeed we spend a lot of money on that system to provide people with security. And yet, if you speak to anyone who’s interacted with our modern welfare systems, it can leave them feeling less secure and frankly, with a shot through sense of self esteem. It leaves people feeling stigmatised, no good about themselves, worried, and often takes away people’s agency to act and kind of take control of their lives. And that seems to me not a human or a sort of humane, if you like, way of the state interacting with citizens. And so I do think aspiring to this idea of relational state capacity, building our capacity to relate to people as humans and to give people agency, and to work with and empower people, is a really important part of the kind of systems we need to build.

Manda: Okay, that sounds brilliant and glorious and there are so many questions arising from that. So let’s have a think, I’m thinking out loud here. I live in a world where I think in longer timescales than you, wherein we emerged 300,000 years ago, and we had an integrative society that looked after everybody. We didn’t have the NHS, but we had a culture where people were cared for and actually infant mortality was very high. But if you got through adolescence you lived your fourscore years and ten, and did so well and healthily absent accidents or famine. Periodically there were big climatic changes. And it seems to me we’re still born with that as our expectation. We’re born expecting to arrive into a society that cares about who we are and what we are. And what we find is we’re in a society where we are cogs in the wheel, whose basic function is to pay bills until we die. And we don’t enjoy it and that’s one of the many reasons we end up with a mental health catastrophe, is because we want agency, being and belonging, and we have a system that destroys those systematically, as you’ve said. One of the things you explore in the book is UBI and a four day week. And you said we couldn’t do those overnight and I’m wondering why not? I would expand UBI to be universal basic services, because it seems to me if you just give people a UBI and you don’t have very stringent rent controls, rent in its widest sense, then you have just created the fastest means of taking public money and shovelling it into private hands ever seen in humanity. But let’s assume we could create a system where the UBI wasn’t just sucked away from everybody instantly. Why could we not do a four day week and UBI? You wrote in the book about four day weeks and how the people who have implemented it, they said you will get 100% of your pay for 80% of the time, provided we see 100% of the productivity. And they did. And everyone I know who went on to a four day week, voluntarily or otherwise, is much happier with a three day weekend. You know, a split. And in the end you could get to 50/50; 3.5 days working, three and a half days not working. Or in the end, we could ditch the bullshit jobs and get to a point where everybody was doing something that didn’t feel like work. And yet we have to start on that path. Why could we not do it tomorrow?

James: I think because these changes ultimately have to be organic. One thing I found most interesting writing the book was the story of how the five day week emerged, which is fascinating. Because we now think of the two day weekend as completely natural, as if it was just something that existed, and of course, we invented it. There’s nothing, absolutely nothing natural about it.

Manda: And we invented it because people were getting drunk on a Sunday and not going to work on a Monday, and the bosses didn’t know when their workforce was going to turn up. And they went, okay, you can have Saturday.

James: It’s a wonderful story. It was a sort of deal struck because people, as you say, people kept getting drunk and not turning up to work. And so the idea I think originally was that at least if people got drunk on the Saturday night, then they’d be hung over in church on the Sunday and not miss work on the Monday. But I raise it because the two day weekend, emerged as an idea over decades and was a social movement as much as anything else. It involved progressive employers saying, let’s try this out. And many of them did find that their factory was more productive in five days than it had been in six, because workers were more refreshed and less knackered, frankly, physically, than they had been. From the union movement. People forget now that the union movement led actually, the first big meeting of the Trades Union Congress in Britain led with working hours as the main concern as opposed to wages. At the time, working hours were very prominent and concern and the call for an eight hour working day. But also government came in. So it was a kind of three pronged attack from progressive businesses, trade unions and government.

James: And it did need to take time for those kind of norms to evolve, for behaviours to evolve. We learned how to do it well. And indeed all these new norms evolved then around the weekend. And so we came to think of the Sunday afternoon as a wonderful thing. And Monday morning is a not so wonderful thing. And Friday night is something that we celebrated. And so they were kind of cultural ways in which we came to sort of live differently, to make a reality of this new pattern of working, that came to breed a whole leisure industry as well. And so businesses sprung up to take advantage of the weekend. And I just think it’s quite a neat example of how, let’s say we had decided to just implement a two day weekend, you know, when the idea first started emerging in the late 1800s. I just don’t buy it would have stuck. Would it have gone well? Would businesses have adapted in the right kind of way? And so I do think you need, to some extent, there to be an organic process of mutually complementary changes, cultural, political, economic and technological, that then embed these changes in ways that are very hard to reverse.

Manda: Okay. I’m thinking of Donella Meadows’ levers of change, her 12 levers of change. And that tweaking policy is the bottom one and that the top is shifting paradigms. And the superorganism or the death cult is hyper systemic. Making single impact changes is not going to be enough. So I can see that UBI, UBS four day week in and of itself was going to hit up against the buffers of a system where the superorganism is still oriented towards profit and growth as its only reason for being. So we need bigger changes. But I’m still looking at the edge of the cliff that we’re hurtling towards and thinking we haven’t got the decades that it took for a weekend to come in. We need to reorient the superorganism as fast and effectively as we can. And what I’m hearing from you is that single impact things, small levers, we’re back to Gordon Brown. UBI and a four day week is a small lever and it’s not the Tim Berners Lee way of looking at the world. We exist in a reality where AI, for instance. I listened to Tristan Harris and Asa Ruskin on Your Undivided Attention last week, and the opening quote was from someone who’s a friend of theirs in Silicon Valley who said, whenever he talks to the people who are engaged in creating the AI, it all comes down to determinism. That as far as they’re concerned, silicon intelligence or silicon life is going to replace biological life. It is determined that it will.

Manda: And this is a good thing. And lighting big, fast fires is exciting. And if we’re going to die anyway, you might as well be the ones lighting the fires, which is frankly terrifying. And I don’t know anyone deeply involved in AI who isn’t looking at it going we have to regulate this, without having the slightest idea of how that regulation could happen. So we have a biophysical reality, we have a materials limit reality, where everyone that I’ve spoken to who looks into how are we going to shift away from fossil fuels to renewables, says there isn’t enough stuff to do that. We have to take our 19 rolling terawatts of Paris and reduce it to five if we’re going to get through, which is enormous. And we have the AI chasing us, and we have forever chemicals in the rain and nanoplastics in the clouds, and agricultural industrial agriculture running off into the oceans and potential ocean death by 2045, last paper I read. All of these are coming together. And if we wait for incremental change on the UBI four day week, all the others are still happening. Is there any awareness from the conversations that you’re having with the people still in the system, that the system itself needs to change? That the superorganism is so complex that we need somehow to change the entirety of the system? Is there anyone working on how we could do that?

James: I think a few thoughts on this. So one is I do think there’s a recognition in the system of the need to be able to change quicker. So there’s sort of a meta question of how can the system get better at changing. And I was very struck, actually, one of the sort of main groups of people that have reached out to me after I published the book were civil servants, essentially.

Manda: People who actually make things happen. Yay.

James: And often people who have been fighting to make change happen quicker and have been recognising that the system is too lumbering, too slow to adapt and see in some of the arguments of the book, new, quicker ways of bringing about change. So there’s lots of live debates, for example, about how does government get quicker at learning? How do you make the learning cycle between not quite getting something right and improving it as quick as you possibly can? And obviously there’s lots to learn from technology there, about fail fast and quickly and iterate and so on. How do you set up teams to do that? And there’s lots of very advanced debates, quite mature debates, I would argue, in parts of the state, about how you set up teams to learn quickly and improve things much more quickly than we’ve been able to historically. So I think those debates about the sort of architecture of the system, they’re I think happening, there’s lots of energy behind them. It’s also this live debate about mission oriented ways of working. How do you get more ambitious about the kind of change you’re trying to pull off? And then how do you build a system that’s capable of delivering? Even beyond the system, if you think about things like how quickly cultural change is playing out and how quickly some of the politics of this are changing, I do think it’s easy to forget that yes, we need to move quickly of course on climate, but I think it’s quite remarkable how quickly some of the politics of these issues has shifted over the last 5 to 10 years.

James: There are those famous charts that show technologies are getting quicker and quicker and quicker to reach scale. But I think arguably social change is too. And if you were to map sort of big social changes around, for example a women’s rights in the past, and compare them to the speed with which LGBT rights played out as a debate. And indeed, now the live debate about gender and trans rights. I think you would see a speeding up there in the way in which these things play out in public discourse. Certainly not always comfortable, you know, when these debates play out quickly they’re not always comfortable and harm can result. But I do think you see a sort of speeding up and we seem to be getting quicker to change the kind of culture behind some of these big issues. So some of the big mechanisms at work, partly thanks, I think, to social media and changes in the way in which we have these conversations, are speeding up as well. So whether or not we’ll get there quickly enough, I don’t know. I’m a borderline optimist on net zero, I would say.

Manda: Okay. All righty. And yes, you’re absolutely right. Obviously the speed of change, particularly of increasing the franchise or changing social and cultural norms is hitting its own singularity. I’d like to look a little bit at how we make things more efficient, how we how we make change faster within government. Because one of the things that I’ve been quite grateful for these last ten years is the inertia in the system, because otherwise we have the furthest right government we’ve ever had and if there wasn’t a degree of inertia in the system, the NHS would not exist anymore. I have a friend who’s deep in the Tory system, and I asked him when he thought the next election would be, because we don’t want to launch a book that’s about an election at an election, and currently we’re planning 30th of May. And he said, oh, don’t worry, we won’t go before we have to because we have to dismantle the NHS before we leave. Those were his exact words. And watching younger members of our family engaging with the NHS with quite young children, it’s terrifying how fast they’re succeeding, endeavouring to dismantle the NHS. So I’m quite glad there’s inertia in the system at the moment. But then, of course, when we get progressive government and we want there to be no inertia. The people who seem to me to be very, very good at the iterations that you’re saying of fail fast, learn quickly are Steve Bannon and the right. Watching them sweep across Europe even. Everyone goes, oh God, we weren’t expecting the right to do well in Sweden. And you only have to dip a toe into the Bannon sphere to see that they’re all talking to each other. They are testing their memes in real time and improving them. And it wouldn’t surprise me at all if the Tories did much better at the next election than all the polls say, because they have the best social media responses, the fastest and the most flexible.

Manda: And if they get into a system that has worked out how to change very fast, I worry. I don’t think Bannon’s 10,000 year Reich can happen because biophysical limits and we’re going to go over the edge of the cliff and that’ll stop it. But it’s horribly close. In the world that you live in, are the changes we’ve made in gender acceptance and trans rights and women’s rights and gay rights, are they moving on a trajectory that cannot be reversed? Or do you think it’s possible that the reversal could happen?

James: Well, I mean, certainly the history of social change has many backward steps as well as forwards, if you like. A lot of the dynamics I talk about in the book are kind of things can get worse before they get better, and often they do. The most kind of unpleasant metaphor being the sewage that piled up in the streets of London, which got to two metres deep on the banks of the Thames before we built the sewage systems that dealt with the challenge. So I think certainly it’s a mysterious process and there’s lots of ebbs and flows, if you like, to how some of these changes play out. I guess I’d say a couple of things. One is I think this question of how can we be less reliant on crisis for change is quite an interesting one. And certainly one of the stories from history that repeats is that we didn’t make the changes we need to until we got to crisis point, and then our hand was forced, if you like, and the sewage got so deep that we had to do something. And I write in the book, slightly glibly, that it would be nice not to rely on a crisis and not to wait until a crisis. So there’s some interesting thoughts about how do you help systems to change themselves? How do you experiment at the level of the system? And, it’s not quite in that space, but there are ideas for mechanisms out there where you give yourself a bit more leeway to experiment in the system to try different things out.

Manda: Can you give us an example of that? Because that sounds really interesting.

James: So a kind of a non-controversial example which has now got quite wide acceptance is this idea of sandboxes. Where you say, we’ll create a safe space that is somewhat protected from regulations in a certain market and will allow people to innovate. See what comes of it, and we’ll shutthings down if they look dangerous, but we will allow people to innovate beyond the rules of the current regulatory system. And it’s a small example, I wouldn’t say that’s going to change the world, but it’s an interesting idea that I think there’s a recognition there that sometimes the system itself gets in its own way and makes it too hard to innovate and change and improve things.

Manda: Is there an example of where that’s been done? Because AI clearly we don’t want a sandbox, actually, because if it gets out, it’s bad. And I’m guessing things like genetic modification, we probably don’t. But are there safer areas where this has actually happened?

James: Yeah. I mean, some of the examples around the pandemic, to be honest, some of the ways in which we developed vaccines so quickly were by saying we’ll give ourselves more leeway to run quickly at this challenge. And you see examples in regulation around things like finance, for example, some of the improvements we’ve seen. Again, you know, these are marginal things, but improvements to things like banking, for example, have come because regulators have said, we’ll give you a bit more leeway to innovate, and we won’t restrict everything by these rules, and we’ll learn from that. So there’s some recognition of that. The other thing I think is just important always to keep in mind, is often one of the things that’s broken at times like this is the old dichotomies in politics. And it’s very noticeable if you look at some of the great reformers of the early 20th century, they didn’t come from necessarily the left or the right of politics, and they often were quite hard to place. So I’m thinking people like Keynes, for example, even Beveridge, quite hard to place on the political spectrum. Some people would have called them sort of centrists at that time, but they weren’t really they were more radical than that in some ways.

James: And so I do think we should be careful. And I say this to people across the whole political spectrum of thinking, this is a sort of fight of the left versus the right. Or indeed the kind of radicalism we need to is radicalism of the left or of the right, or indeed of the centre. You know, many of the ideas I explore in the book are sort of potential big ideas that might come to be a new common sense in decades time, are quite hard to place on the political spectrum. It’s not immediately obvious where a universal basic income or even a four day week sit on the spectrum. There’s some quite interesting advocates for basic income from the right of politics as much as from the left. And so I think, I take your points about sort of where we are politically, but I do think we should as much as possible try to not be too inhibited by the dogmas of the 20th century, or the way in which we thought about politics in those decades, because that might be one of the things that’s constraining us from building the kind of society we would need in several decades time.

Manda: Okay, we’re running out of time. But I would just like to delve into this a little bit more deeply, because this feels really exciting. Because there is a lot of my life where I think left and right is exactly as you said; it’s the politics of the last century, and it’s it’s pointless. And yet I read Democracy in Chains by Nancy McLeod, and she detailed very clearly the the very hard right in America and their strategy for owning the political sphere. And I read that in 2016, and I’ve watched it play out in the nearly a decade since. And Bannon is quite clear that he wants a white patriarchal theocracy. And he said quite clearly to Michael Moore, Michael Moore asked him, why is it that the right wins and the left doesn’t? And they were still in left and right. And he said, because we’re going for headshots and you’re all still in a pillow fight. There is nothing we will not do to get what we want. And they have real clarity. And for them, right/left still exists. And I would like to live in a world where it doesn’t because it’s it’s not going to get us to a world where people and planet flourish together. The concepts of left and right are completely inimical to that.

Manda: But if we have one side that is going for headshots and we’re not even in the fight because we don’t think it’s a fight… Now I’m blatantly curating ideas for the next book, actually, because that’s where I’m going to take it. But let’s carry on with this. I just realised that’s what I’m doing. How do you see this working? Because I would like to live in a world where left and right are irrelevant, we just pick the best people and we pick the best governance system. And it’s probably a distributed democracy because people on the ground know best what needs to happen around them. As long as we have a value system that is not based on economic growth, but is based on connectivity and flourishing. In the corridors of power as they exist at the moment, is there a move at all towards dissolving left right? And if so, what would arise again, as the value system that underpinned the governance structures that would move forward?

James: I think partly I think it’s important to be cautious about the America case study, if you like.

Manda: Apart from the fact that it’s a basket case and quite scary to watch. Yes.

James: It is scary to watch. And I think actually one of the things that is somewhat problematic, is that it is unique in many respects, the kind of crisis of governance in the US. And I think many people wiser than me have pointed out that although there are sometimes attempts to replicate the culture wars that are taking place in the US, in the UK, if you drill into the data, it’s not really happening. And there’s not really, if you drill, it’s not really getting traction. I think some people would like this to be more salient in people’s lives, really if you speak to the median voter and look at what it will take to win the next election, the culture war is not the salient topic that it is in the US, it genuinely is. Polarisation, again, there is some evidence of polarisation in the UK and certainly around Brexit there was a sort of schism, somewhat different to left/right actually. But again, not nearly the same level of polarisation, not nearly the same level of media polarisation, for example, not nearly the level of distrust.

Manda: They’re trying though, aren’t they? Because GB News is doing its very best to be on the right of Fox.

James: Do you see some seeds of it, for sure. But I think there are uniquely American explanations for quite a lot of what is happening there. And I think it’s easy to sort of overinterpret us as necessarily following in Europe and in the UK, as following down that path. But I do think that one point stands, which is one thing the left, I think or progressives more broadly, would need to do is to have that more positive account of the future than progressives have thus far been able to set out. And I do think personally, my general view is that the best way to counter the more nostalgic rhetoric of restoring some kind of lost past is to talk more positively about the future and convincingly.

James: Not not just to talk in rainbows and to talk in terms of a promised future that doesn’t feel real to people, but to convince people that it is doable and that we are we are capable of building something better and to start showing examples of that. And so I do think that’s important. And I would come back to this point that the reason I think the word progressive is quite useful, as opposed to the word left, is there are often unpredictable and quite surprising coalitions of people that come together to build the new thing, if you like. And again, if you look at the kinds of ideas that you might describe as being part of a new paradigm, for want of a better word, they’re not easy to place on the spectrum. I’ve talked a lot in my book and elsewhere about new ways of thinking about well-being, for example. New institutions we could build around mental health, around helping people to live good lives with chronic physical conditions, around forming communities of people that help people live well together as they get old. Around tackling loneliness. And the ideas in these spaces, I’m not sure they are ideas of the left or the right necessarily. They’re they’re sort of new ideas. They’re quite fresh ideas. You could argue progressive ideas in that they’re about making progress towards a better future. But in a way, they’re quite surprising ideas that are quite hard to place. So I think we need to be relatively open minded and forge surprising coalitions and work on ideas together in ways we might not have anticipated. And my guess is that’s where we build the new thing from, as opposed to retrenching into the kind of how do we fight the ideas from the right, as people of the left, for example. My guess is that framing doesn’t get us to the new thing so much as sustains the old patterns that we’re stuck in.

Manda: Okay, brilliant. Yes, that makes a lot of sense. Alrighty, so many more things. Okay, final question, because this I think is salient. In my future we have a post-growth economy. We probably get to it with degrowth, but that’s only because I listen to a lot of Jason Hickel. In your future, what is the political economics? Is it a post-growth? Is it a degrowth, or are we finding a different kind of growth?

James: So I get to, and these are horrible words, but I get to something more like inclusive growth, broad based growth, sustainable growth.

Manda: Okay. How do they work? Tell me about those.

James: So these kinds of words. And the reason I say these words as opposed to post growth or no growth, is because I do think the seed of insight that I like from the no growth movement or the post growth movement is that this infatuation with GDP as a construct, is when you zoom right outand get some perspective on the situation, an odd path to have gone down. And I do think it is true to say that we’ve forgotten that a tool like GDP can be a helpful tool for thinking about certain aspects of what we need to build together as a society. But it is a small part of the picture. For example, of course, growth needs to be sustainable and to take place within planetary boundaries. And of course, that is, if you like, a non-negotiable.

Manda: How does that happen? Growth and planetary boundaries? You’re trying to expand something within places that we’ve already exceeded in some areas.

James: Well, I think contingent on certain questions like, do you have carbon intensive energy, for example? And if you can get to a place of zero carbon energy sources, then you can expand your need for energy and make more use of energy without without breaching certainly the carbon planetary boundary.

Manda: But you’re going to reach then other material limits. If you don’t reduce the outflow, so if we don’t reduce FAS in the air and in the water, if we don’t reduce industrial agriculture outflows, it doesn’t really matter what the power source is. We’re still a species in over overshoot and the effluent is still not quite sewage two metres high in the Thames, but it’s the biophysical equivalent.

James: For sure. We need a system that is capable of respecting these kinds of boundaries. That is definitely true. But I think generally I think for me, the shift that needs to happen is less to a sort of no growth and more to a conversation about the role that growth plays within the wider system of our lives. It’s very interesting talking to people about this, I think this has got real wind as an idea, talking more broadly about people use the phrase human flourishing as the kind of broadest conception of what is it we are trying to achieve here together. When we talk about progress.

Manda: Human and planetary flourishing.

James: Absolutely. Cross-species flourishing, whatever phrase you want to use. And it’s beyond wellness. The wellness debate that kind of came to more salience in the 90s and 2000, where we were talking about broader measures of human wellness, for example, and happiness and utility and those kinds of questions. It goes beyond that to think about what does it take for people to flourish truly in their lives? And one aspect of that is material resources, and we know that. But it’s certainly not the only aspect. And it would include things like our caring relationships, you know the quality of relationships we have with each other, the sustainability of the ways in which we’re living. Maybe I’m bringing personal prejudices to the table, but personally, I prefer a conversation that is about broadening and having a richer conversation beyond growth, inclusive of questions of material. You know, how do we get the kind of material standards we need? But that goes broader and thinks more holistically, rather than rejecting outright the question of material living standards, which for me remains important.

Manda: Okay. And are those kinds of conversations happening within the superorganism and the corridors of power?

James: You know, I genuinely think they are. I was speaking with someone the other day, in the corridors of power, speaking to someone about work Oxford University is doing, thinking about human flourishing. And these were the words they were using; what would it look like to have a richer understanding of human flourishing, ways of measuring and understanding the extent of human flourishing and building systems to support that? And if you think about the corridors of power, you would think about Oxford University. So it gives me hope that some of the centres of our intellectual debate and where our future leaders are being trained, and the kinds of ideas that they’re discussing, these, these broader and richer ideas about the kinds of systems we should be building, I do think they’ve got energy and momentum behind them.

Manda: Brilliant. I would really like to think that our future leaders are not all going to come from Oxford, but true.

James: True, I’ll say that.

Manda: But if the ones from Oxford are gaining this and they can disseminate it very effectively, because that’s what they’ve been trained to do. James, we are so out of time. Thank you. Is there any last word that you wanted to say to everybody other than, I think you should all read James’s book, which is brilliant. Is there a sequel coming out? Are you going to write another one?

James: I am working this year. This is my New Year’s resolution is write the second. So, watch this space.

Manda: Yes. Please tell me and we’ll have you back. We could talk about the next one around lunchtime, whenever it’s ready. Look forward to it. Anything else that you wanted to say?

James: Only hope. I would just end with hope. Because as I said, right at the start, I didn’t set out to write a hopeful book and I ended up writing one. And partly because I think there’s reason to hope, I genuinely believe that. But also because if we don’t have hope, we just have anger. And, you know, the formula is anger plus hope. So I would just end with hope.

Manda: Fantastic. Thank you. James Plunkett, thank you so much for coming on to the Accidental Gods podcast. This has been enlivening and enriching. Thank you.

Manda: And that’s it for another week. Enormous thanks to James for the depth and breadth of his insight, for caring enough to swim against the stream, and for having the visions of a radical future that could work within the current system. All we need to do now is elect the people who actually want to make this happen, and then empower them so that they can. Inevitably, as soon as I hit the button to stop recording, we started talking about spirituality and our deep spiritual yearning to connect with each other and the web of life. So one day when we come back, James and I will look into that again. But we do talk about that on other episodes of the podcast. And in the meantime, if there are ways in which you can become involved and can make the politics that exist now better, whether it’s joining South Devon Primary in creating progressive primaries to help us not elect another Tory government, or joining the Humanity Project that we spoke about last week with Alex Lockwood, looking at different ways of creating distributed democracy and making those work.

Manda: Politics shapes the world that we live in. It is less than a year now until the next election in the UK, and if you live in other countries in the Western world, you may have elections coming this year. The current system may be broken, but the current system is the one that shapes our world. It matters that we elect people who get that we’re in a meta crisis, and understand the different ways that we could be doing things to make them happen, to bring them into being. So if you can help with that, please do.

Manda: And that apart, we will be back next week with another conversation. In the meantime, thanks to Caro C for the music at the Head and Foot. To Alan Lowles of Airtight Studios for the production. To Anne Thomas for the transcript. To Faith Tilleray, for all the tech behind the scenes and the conversations that keep us moving. And as ever, enormous thanks to you for listening. And if you know of anybody else that wants to understand the ways that we could shift our democracy, then please do send them this link. And that’s it for now. See you next week. Thank you and goodbye.

You may also like these recent podcasts

Falling in Love with the Future – with author, musician, podcaster and futurenaut, Rob Hopkins

We need all 8 billion of us to Fall in Love with a Future we’d be proud to leave to the generations that come after us. So how do we do it?

ReWilding our Water: From Rain to River to Sewer and back with Tim Smedley, author of The Last Drop

How close are we to the edge of Zero Day when no water comes out of the taps? Scarily close. But Tim Smedley has a whole host of ways we can restore our water cycles.

This is how we build the future: Teaching Regenerative Economics at all levels with Jennifer Brandsberg-Engelmann

How do we let go of the sense of scarcity, separation and powerlessness that defines the ways we live, care and do business together? How can we best equip our young people for the world that is coming – which is so, so different from the future we grew up believing was possible?

Brilliant Minds: BONUS podcast with Kate Raworth, Indy Johar & James Lock at the Festival of Debate

We are honoured to bring to Accidental Gods, a recording of three of our generation’s leading thinkers in conversation at the Festival of Debate in Sheffield, hosted by Opus.

This is an unflinching conversation, but it’s absolutely at the cutting edge of imagineering: this lays out where we’re at and what we need to do, but it also gives us roadmaps to get there: It’s genuinely Thrutopian, not only in the ideas as laid out, but the emotional literacy of the approach to the wicked problems of our time.

Now we have to make it happen.

STAY IN TOUCH

For a regular supply of ideas about humanity's next evolutionary step, insights into the thinking behind some of the podcasts, early updates on the guests we'll be having on the show - AND a free Water visualisation that will guide you through a deep immersion in water connection...sign up here.

(NB: This is a free newsletter - it's not joining up to the Membership! That's a nice, subtle pink button on the 'Join Us' page...)