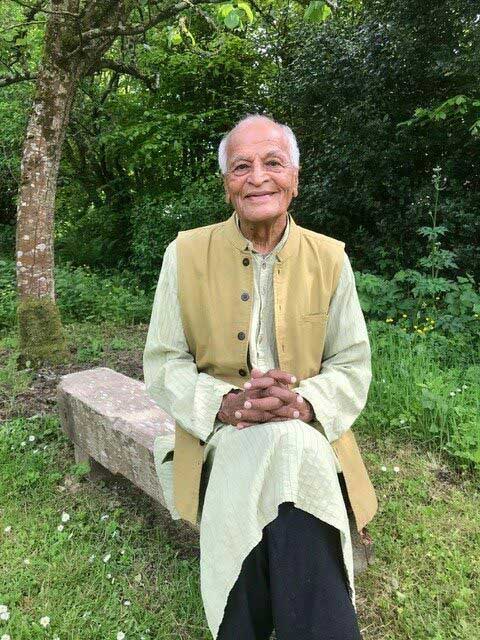

Episode #159 Food, Farming and Feeding the Soul: with Satish Kumar in conjunction with the Oxford Real Farming Conference

The Oxford Real Farming Conference (ORFC) is one of the highlights of the regenerative farming year. Running from 4th – 6th January, this year sees a return to the in-person conference as well as a continuous rolling on-line programme. As part of the lead in, Accidental Gods was honoured to speak with Satish Kumar, one of the god-fathers of the regenerative, redistributive movement.

Satish is one of the absolute titans of the Regenerative movement in the UK. In 1962, he and and one of his fellow Jain monks made an 8,000 mile mendicant peace pilgrimage around the world, stopping in the capitals of the nuclear nations of the earth: Russia, USA, France and the UK. He settled in the latter and soon became known for his work in connecting people and ideas. He founded the Small School in Devon, Schumacher College and Resurgence Magazine (now: Resurgence and Ecologist Magazine).

This week, we teamed up with the conference to speak with Satish as he prepares to head to Oxford. We explore more deeply his concepts of education, food and farming and the re-connection of people to the living web of life. He ends with a meditation, similar to the one he will lead on the Friday morning.

Now entering its 13th year, the Oxford Real Farming Conference (#ORFC23) is the unofficial gathering of the agroecological farming movement in the UK, including organic and regenerative farming, bringing together practising farmers and growers with scientists and economists, activists and policymakers in a two-day event every January.

Working with partners, the conference offers a broad programme that delves deep into farming practices and techniques as well addressing the bigger questions relating to our food and farming system. It attracts people from around the world who are interested in transforming our food system.

ORFC has always been the place to share progressive ideas. Subjects include agroecology, regenerative agriculture, organic farming and indigenous food and farming systems. The broad programme delves deep into farming practices and techniques as well as addressing the bigger questions relating to our food and farming system.

Crucially, it has always been the participants who provide the ORFC programme. The sessions reflect their diversity, ranging from the intricacies of soil microbiology to new kinds of marketing; setting up a micro-dairy to the value of introducing mob grazing and agroforestry to the farm; from the joys and tribulations of farming to the kind of economic structure we need to support the kind of food system we need. It is this diversity of participants and interests that keeps ORFC alive and growing.

Episode #159

LINKS

Fere online tickets are available to all those in majority world countries – this is defined as anywhere outside Western Europe, the US, Canada, Japan, Australia and New Zealand. The conference works with the interpretation collective, COATI, to make sure sessions are accessible.

Follow the conference on Twitter, Instagram or Facebook for all the latest news and speaker announcements.

In Conversation

Manda: This week we are delighted to be in partnership with the Oxford Real Farming Conference, which takes place online and this year again in person, from the 4th to the 6th of January. This is the 13th year of the RFC, which is the unofficial gathering of the agro ecological farming movement in the UK and to a large extent around the world. It brings together practising farmers and growers with scientists and economists and activists and policymakers. There was the year when Michael Gove actually turned up at the RFC, when he was minister for Defra, whatever it was in that particular government. And for these three days, Thursday, Friday, Saturday, there is this huge event. There are many streams of many panels across a really wide range of subjects involved in the food and farming system. This is a place where people come together to share progressive ideas about food and farming.

So we have agro ecology, regenerative agriculture, organic farming, indigenous food and farming systems, the health of the soil, mycobacteria, carbon farming as a thing or not. It’s huge. And the speakers are the kinds of people that you normally see on TEDTalks. There’s Vandana Shiva and Zach Bush, Cris Mage, Rose Lewis, Merlin Sheldrake and Satish Kumar. And the organisers of the conference asked if I would be interested in speaking to Satish on the podcast, so that we could broadcast it a week ahead of the conference, starting as a taster and an opener. And of course, I said yes. Satish Kumar is one of the absolute founding heroes of this movement. Way back in 1962, when he was a Jain monk, he and one of his fellow monks went on a mendicant walk, taking in all five nuclear capitals across the world. So from New Delhi to Moscow to Paris, to London to Washington. I’m not sure it was exactly in that order. But they walked and they walked without money and they depended on the kindness of strangers. And their aim was to promote a non-nuclear future. And to the extent that we are still here and there was no nuclear war, they succeeded. And then Satish settled in the UK, where, as you’ll hear, he founded the Small School in Devon.

He founded Schumacher College, where I studied regenerative economics. He founded Resurgence magazine. And all the way through from then until now, he has been one of the most powerful and respected voices in the whole of whatever we want to call this movement towards a flourishing future. So it was an honour and a privilege and an absolute delight to be able to talk to Satish. And as is often the case in these conversations, I hit the record button early on, partly because I wanted to do a sound check and partly just to kind of get warmed up. And I asked Satish what was most alive for him? And he had just come off a call with two people in New York who wanted to set up a small school similar to the one in Devon. And what he said then seemed to me so alive that I wanted to keep it for you. So people of the podcast, please do welcome Satish Kumar. And let’s step straight into the conversation, with his recounting his previous conversation with people in New York who want to set up a small school.

Satish: These two people, a mother and daughter, want to start a school in New York, following the example of the small school I started. And one of the features of the small school I started was that all our children will learn to grow food.

Manda: Right.

Satish: Because children should learn to touch the soil and plant the seed and see the miracle of the seed becoming a plant and that plant becoming fruitful, and tomatoes or potatoes or whatever. And then how that one little seed of tomato becomes a plant. And that plant has 100 tomatoes and each tomato has 40, 50, 60, 100 seeds. Amazing what nature can do! So that was the kind of philosophy of the small school. The children should learn to know the miracle and the magic and the beauty and the glory of nature and the soil. And so I not only started a small school, I also started Schumacher College, and we apply the same principle there. We have a nine acres of garden and all our students learn there how to grow food. Last year, these our students grew £30,000 worth of food in the nine acres of garden. So the small school and Schumacher college both have this principle of connecting education with the land and the food and agriculture and nature. Now, the other thing I want to say, connecting with that thing, is that not only the Small School and Scumacher College, every school in the whole of England, and not only England but Britain, and not only Britain but Europe and the world. Every school, every college, every university should be associated with a farm or with a garden. And all children, young people, students, university students, college students; they should spend some time working on the farm, working in the garden. growing food. Education and growing food must be brought together and schools should have a farm or a university should have a farm or a garden where professors, teachers, graduates, everybody, even chancellors, vice chancellors; they all participate in cooking and gardening and growing food. For food is what we survive on, we live on. But at this moment our education has become totally disconnected from food and farming and gardening and cooking. And so this is kind of my life’s mission; and I’m delighted that now lots of farmers are also thinking the young people should learn and come to the farm and help the farmers.

Manda: Yes. Brilliant. Thank you. This is brilliant. And this is a perfect introduction to the Oxford Real Farming Conference and everything that we want to talk about as a lead in to that. The idea that if education were intrinsically connected to the land and to the growing of food and to the cooking of food and all of its preparation. I vividly remember my time at Schumacher washing up dishes, with you actually. And cooking, just chopping onions together is an extraordinary way of dissolving boundaries and getting to know people in a way that feels organic in it’s truest sense. That there’s something about the sharing of making your food or the sharing of growing your food or the sharing of cleaning up after, that really connects people at layers deeper than our cognitive senses might allow.

Satish: Yeah.

Manda: So I’m interested as we head towards the RFC and there’s a huge emphasis this year on young people on the land and bringing young people into farming. And what we’re finding here in South Shropshire is a grand disconnect; of a lot of people who really want to come onto the land – and I live on a smallholding. We’ve got 28 acres, it’s mostly quite hilly, but still – we want to bring young people here. But getting planning permission for places where they could actually live is proving really hard. And you, I think, have connections at some of the upper echelons of policymaking. Have you got any instinct that there is an understanding at governmental level of how important this is? Or is it something that we need to really begin a whole movement towards that?

Satish: I think there’s a long way to go, because the government is still wedded to economic growth and industrialisation. And industrialisation is seen as the symbol of progress. So they are industrialising agriculture. And you remember after the Second World War, when the United Nations met, the president of the United States of America made a speech to say that the world is divided into two parts: the developed part and the undeveloped part. The developed world is world industrialised and the undeveloped world is agricultural. And so our mission, said the president of the United States, is that we should industrialise the agricultural world. So now, more and more of our industry is encroaching and industrialising the agriculture, so humans are less and less involved. So it may be in the UK less than 2% of people are engaged in agriculture. And those 2% of people even don’t do any agriculture. They just manage the machine, they manage the computers, they manage the robots, they manage the tractors and big combine harvesters and big machines. So you get industrialised agriculture and humans are no longer involved. And also it is seen that if you are clever, if you are smart, if you are educated, then you don’t go into agriculture. You go into law or doctor or civil service or some industry or some business or some banking or insurance – all those things. Agriculture is only for those who are not smart, not clever, not educated, and therefore they become labourers, so they become agriculturalists. So this industrialisation of agriculture has been and still is very strong in the consciousness and the psyche of the government ministers and leaders. Whereas I think that, in my view, farms should be farmed by farmers and not so much by machines.

Satish: Of course I’m not against machines. You can use machines as tools to help the humans, to make work a bit easier. But don’t let the machine take over and make the human redundant and unnecessary. So our agriculture has become so industrialised that you have factory farms; say for example, 20,000 cows or 50,000 chickens. They never see the light of the day, their whole life they stay inside and they are fed by computers and robots and they are milked by computers and robots. Humans have very little role to play. I think, in my view, I’m old fashioned, but in my view this is a tragedy. I would like to see humans doing agriculture. I would like to see 20-30% of people in Britain still engaged in agriculture. And industry should be for making machines; like cars and computers and cameras and railways and aeroplanes and all that you can make by machine. But food should be grown by hand. That to me is more organic. Because organic means organs. Human body is organ, hands and feet are our organs. So if we do agriculture with our organs, that is the true agriculture; the true organic agriculture. I want more people, and this is why my plea is that we should teach young people in schools and universities, to learn how to grow food, how to cook food, what is healthy food. That’s my great wish.

Manda: Thank you. And it’s obviously the great wish of most of the people who are involved in the RFC. A great many of the panels, both in-person and online, are going to be looking at this link between people and the land; small farmers cultivating small spaces. And also between human health and the land. I’m noticing they’ve got Zach Bush, who’s very widely known for his understanding of the human microbiome, talking about the link between the health of our gut bacteria and the soil bacteria and how the interchange of those two promote human well-being.

Satish: I agree with you totally that human health and food are absolutely and totally interdependent and interconnected. Why do we have so many ill people in the UK? Our National Health Service is falling apart, and every year our government puts billions and billions and billions of extra funds and yet never enough. And people are so ill. Why? We never ask. We are always producing more medicine, more medicine, more medicine. But we don’t ask why people are so ill? Why our country is so unwell? We never ask. And the answer is that we are not eating right food. We are not eating good and healthy food. Health and food are totally interconnected. You cannot have healthy people on a bad diet. So if you want to really look after people’s health, don’t put so much money in National Health Service, put more money in agriculture and good food. And I think all the kind of unhealthy junk food should be if not banned; I think that it’s criminal to produce junk food, unhealthy food; if not banned, at least taxed 200% or 500%. So nobody is encouraged to buy. So food and health are absolutely 100% interconnected. And if we are not going to have a good food, we are not going to have a good health. However much money, more billions more trillions you put in National Health Service, is not going to help. It’s the food which is the real medicine. We have to get health and food together.

Manda: Yes. And yet in the UK, we have a government that refused to even create a sugar tax. And I remember, I think when I was at Schumacher or possibly shortly after reading a book called The Hijacking of the American Mind by a doctor called Robert Lustig. And he was describing how the combination of big business and industrialised food systems were very consciously creating addictions for carbohydrates, fat, sugar and salt. Such that, exactly as you said, we have this pandemic of things like type two diabetes where people are not only clinically obese, but they’re also lacking a lot of the micronutrients that we would get if we ate a balanced diet. I read something the other day that we should be eating 30 different types of vegetables per week, or at least 30 different types of plant matter per week. And I would struggle to name 30 different types of plant matter, to be absolutely blunt, never mind finding them to eat them. But it seems like a good idea. So if we have a system where very big money is invested in maintaining industrialised agriculture, which as you described, is horrendous. There was a tweet, Robert Reich, who’s one of the very big commentators in the States, tweeted this week at the time of recording that a company called Albertsons just bought Safeway. And now a bigger company called Kroger is buying Albertsons. And combined they control 22% of the US grocery market, with a revenue of over $200 billion. By the time you add Walmart, these brands control 70% of the grocery market in the US and they therefore have an extraordinary vested interest in maintaining the addictions to the industrialised food that makes them a huge amount of money. Because it’s basically cornstarch and a few added extra bits to get the dopamine hits. How do you see us moving beyond this control by giant agriculture and giant business, of the food of life?

Satish: Yeah, I mean, that’s a very good, very big question. I don’t know if I have the answer, but I can only say that we have to start a new movement at the grassroots level. And the Oxford Real Farmers Conference is a very good start. Where people can come together and say, We are not going to accept this monopolistic and very centralised and very controlled food market. And where food has become a commodity. We want to see food is sacred. Food is for health. Food is for people. Money is only a means to an end. Food is not for making money, food is for keeping people healthy. Also, food is sacred and therefore growing food is a spiritual activity. We are growing food out of love for the land and out of love for people and out of love for ourselves. And so food should be a spiritual practice, a sacred action, and not just a commodity to make money and profit and market commodity. So how you do that, you have to start somewhere small. Like a great river starts somewhere in the hills, like a little spring, and then many, many small tributaries join in. And then that becomes a great river. In the same way, this river of transformation, this river of new movement, has to start somewhere small, like Oxford Real Farming Conference. And then many, many people have to join in. And slowly it may take time; five years, ten years.

Satish: But I think the future of food is bleak at the moment and the health of people all around the world is bleak at the moment. So we want a healthy planet, healthy people then we have to have healthy food. At the moment,the planet is sick. Global warming, climate change and pollution and waste and oceans full of plastic and rivers full of sewage and soil full of chemicals. Healthy people, healthy planet that’s connected. And if we produce rubbish more and more, that’s not going to bring health to people and not going to bring health to the planet. How long we are going to survive like this? We have to look after the planet, not for one year or five years or 50 years or 500 years, but for millions of years to come. And so in order to have our planet and our people healthy and well for millions of years to come, we have to change our ways. If we go on polluting and wasting and destroying our climate, our environment, our oceans, our rivers, our soil, our farmland and our human health, how long are we going to survive? So for the future generations, we have to wake up and we have to change our ways. We are not doing any good service to future generations by polluting and wasting and creating this kind of this kind of climate change and chemical agriculture. This has to change.

Manda: So what is your view then on the current move that’s gaining a lot of ground amongst people… Who felt until recently to me they were allies in this movement. And now I’m sensing a split between those who want to rewild the land and for people to eat food that has been grown, as far as I can tell, in chemical laboratories and large metal vats; the kind of pseudo proteins or mica proteins or whatever they’re called. I find it very frightening, because it feels to me as if this is yet another disconnect from the land. But the argument that is put back the other way is that then you leave the land to Rewild and that actually it’s going to be overall beneficial. And yet I still find myself feeling that this is inherently going to create less empathy for the land in the long term. And I wonder where you stand within that? It may be that you’re able to straddle the line and stand on both sides.

Satish: On the outset, I am totally against this artificial protein and alternative protein and factory made food. I am not in favour. I would say that there’s a middle way. We can grow food with good farming and we can also have good wilderness. There is no contradiction. Apart from human species there are 800 million species on this planet Earth. They don’t produce their protein in factories. They are all, lions and tigers and deer and snakes and birds and all the animals, all the species, they live on a natural food. So wilderness can also produce food. And my friend Isabella Tree, she has got the Knepp estate and she produces a lot of food there in wilderness. So wilderness and food production is not contradictory. But I’m not saying that all land has to be made into wild. You can have such an amount of land where you produce food, but food should be produced in a proper and healthy way rather than in a kind of industrialised way. So that is my plea and I want those who eat food must respect and must engage in growing food and cooking food.

Satish: We just eat, eat, eat and not grow. That is lazy. And that’s not going to survive very well. So my thinking is that you can have a combination of wild and combination of properly, organically, humanely produced food and not factory farms and not mass production and mass consumption on a large scale. Small is beautiful. Small farms where humans work. Let the machines work and produce machines, but let human hands produce food. That is my thinking. And we should have good food. Food is not only protein, food is celebration, Food is relationship, food is family coming together. Food is friends coming together. Food is community coming together. If we have no food together, our culture, our civilisation will be doomed. Therefore, please don’t allow these factory farms and this mechanised production of alternative or artificial protein to take over. We want to protect our food as a sacred food, and we want to eat good, delicious, fragrant and healthy food every day. Two times a day, three times a day. We don’t want to live on pills.

Manda: Thank you. We definitely don’t want to be eating pills. And I’m noticing in the program that Vandana Shiva will be talking quite early on the first day, about her life of campaigning for small scale farmers. And she’s completely committed to creating networks of small scale farmers around the land. And it seems this year in particular at the RFC, there’s going to be a lot of people talking from what, after the Second World War, they called the underdeveloped world because it was not industrialised. About how they can begin to regrow their agriculture programs, how they can reduce the inputs of fossil fuel, create pesticides and fertilisers and move instead. There’s a program on the Thursday: Finding Solutions to the Fertiliser Crisis; practical on-farm innovation for Home-grown fertility. And it seems to me that this is something that we haven’t fully got into the mainstream. That there seems to be a media narrative conflict, between the people who want to continue industrialised farming and the people who are suggesting that small scale organic, biodynamic permaculture style farming, where you create all of the fertiliser on the farm, is innately going to grow the soil. We’re not just going to grow the microbiome of the soil, we’re actually going to grow the physical depth of the topsoil. And that by doing that we are sequestering carbon and becoming a large part of the solution to our multipolar crisis of which one big pole is the climate emergency. And I wonder, as you talk around the world, to what extent is farming as a means of sequestering carbon, something that people are aware of, or is it something where we need to get the story out much more clearly and much more strongly?

Satish: Yes, I think if we did a proper way of farming, if we did a proper way of agriculture, then carbon sequestration is naturally achieved. I have visited a number of big farms; in Italy for example, there’s a farm called Fattoria la Vialla, and the University of Sienna has made a research and observed over a number of years, how the carbon sequestration has achieved on that farm. And if all the farms of the world farmed like La Vialla in Tuscany, there will be a global cooling, not global warming. So you can sequestrate carbon in the soil, by putting your attention to the soil and building the soil. Our great challenge for our time is to build soil, make soil, protect soil, soil the source of life. Soil is not just a source of economy. Soil is the basis of life. And you know, the word soil in Latin is humus; and the word human comes from the same root as humus. So the human beings are literally soil beings. So protecting the soil, maintaining the soil, building the soil, is the way to bring carbon back into the soil and address the problem of climate change. So good agriculture is the antidote to climate change and good building Soil and good agriculture is the way forward for the protection of human health. So from the point of view of a human health, a point of view of planetary health, we need good agriculture. And good agriculture means more people involved in agriculture and not machines involved in agriculture.

Manda: And then because we live in the world of neoliberal capitalism, we have to get around the idea that as soon as people are even slightly aware of this, then carbon farming becomes a thing and it becomes a thing that they can use to greenwash whatever else they’re doing. Because they buy out farms and claim that they’re sequestering carbon and that allows them to carry on with business as usual, in every other way. There’s what looks like a fascinating panel at 2:00 on the Wednesday looking at the business of carbon farming and other nature based solutions and whether they are a panacea or a disaster. And I’m thinking back to Schumacher and doing the regenerative economics course and trying to figure out ways that we could shift the economic focus of the world, from growth and profit to something where everybody’s needs are met within the boundaries of the living planet. And yet again, I’m still interested in… You are someone who…You talk to people all around the world. You talk to people at very high echelons of government. Do you get any sense that there’s a movement at the UN level or thereabouts, towards shifting away from the profit motive, to something that would allow small farmers to return to the land. Allow agribusiness to just quietly dissolve and give up. Or are we going to be in this duality for a while longer, do you think?

Satish: The small kind of signs of hope at the UN level and the EU level, where people are questioning the way we do agriculture and the way we produce food. And so I have been involved with some groups with the UN and some groups at EU in Brussels and also in the UK. Some people are advising, for example, Ben Goldsmith, he’s advising the Government and his brother Zac Goldsmith, advising the Government to bring more ecological perspective in economics. Economy and ecology cannot be separated, because economy means management of the planet home and ecology means knowledge of the planet home. If you have no knowledge of the planet home, how are you going to manage the planet home? So every economic class in universities and schools, particularly for example, London School of Economics. I have already suggested to the Vice-Chancellor of the London School of Economics that they should change the name of their university and they should call it LSEE; London School of Ecology and Economics. Without ecology, economics is a disaster and without economy, ecology cannot be managed. And so we need to marry the ecology and economy together. And this is what we are doing at Schumacher College. Our economic study is regenerative economics. So regenerative economics means that ecology and economy are studied together and that is a great challenge for our time.

Satish: Unfortunately, at the level of UN and EU and the British government and European governments, they are still controlled by the vested interests of business and economy and they are prepared to sacrifice everything at the altar of economy. They are prepared to sacrifice the interests of the planet. They are prepared to sacrifice in the interest of humans. They are prepared to sacrifice the health, everything. They only want economy, economy, money, money and jobs. Jobs should be good jobs. Work should be good work and not work, which is polluting, wasting and causing ill health. And so I think the change from the UN and EU and governments is going to come much later. The real change and the real revolution and real transformation will come from the grass roots. And this is why organisations like Oxford Real Farming Conference and many other small scale local and decentralised grassroots organisations, building movement from the bottom up. That is for me a greater hope than UN and the governments and EU. They are little bits of hope, kind of signs of change there, but very little. They are still wedded to economy, economy, economy and I think economy is bringing disasters to our country. Economy without ecology is not good. Therefore ecology economy should be brought together.

Manda: Brilliant. I am so looking forward to the moment where the LSE changes its name to the LSEE. That would be such a big step, actually. People would notice that one. So looking at the wider picture; including food and farming but broader; given that we feel to me as if we’re on the edge of many tipping points, some of which are potentially catastrophic. Do you have a sense of areas where change genuinely can happen, that it would be worth a lot of us putting our energy behind to help move those tipping points along?

Satish: Yes. For me, there are two areas where we need to put our efforts. The one area is future generation. Because the present generation is already kind of conditioned and kind of has got a sort of fixed world view. And therefore it will take a lot of effort and time to change. But future generation, our young children, kids and young people in schools and universities, they are not yet conditioned; they are not yet brainwashed. If they can be given a proper education and reconnect with nature, with land, with farming, with food, with health. I think there is for me a hope. And I can see that lots and lots of young people are asking for it. I mean, people like Greta Thunberg and people – many, many hundreds of thousands of young boys and girls – are marching Fridays for the future around the world. Asking for a better education. So if we can bring ecology, environment, land, food, these issues into our schools and universities and look after our future generation, there’s a greater hope for me. That’s the one area I would like us to put more effort and more focus and more energy.

Satish: The second area is farmers themselves. I would like to create a kind of movement where we support the farmers and we also bring this point to the farmers that food is not only to make money and profit. Food is to feed people, and food is to look after the land and look after the soil and look after our forests and look after our environment. So this holistic approach has to be promoted among the farmers. Don’t wait for the government to change the laws; start wherever you are, your journey and look after your land. Don’t see land as a source of making money. See land as a source of food and make money with some other ways if you need to. But food and farming should be seen as a sacred. So we need to work with the farmers more. And I’m very pleased that Oxford Real Farming Conference is bringing farmers together in Oxford to highlight these issues. And we need to do more and we need to have similar conferences in Wales, in Scotland, in northern England, in Cornwall, in Devon, in everywhere. And we need to spread this big movement, that food is sacred and we must look after food. Food is the source of good health for people and planet. So these are the two areas I would like to focus. Young, new and next generation. And the farmers themselves.

Manda: Brilliant. Excellent. So it seems to me in both of those, we’re talking about creating new stories. And this is my field because I write novels and I write TV scripts and again, we’re hitting this disconnect where the big publishers and the gatekeepers of television movies are all the old generation, and they do have a very fixed worldview. And I’m wondering if you know of, or could imagine, ways in which we could create stories, novels, poetry, films, movies predicated on the ideas that you’re talking about. On the sacredness of the land, on the sacredness of growing food, on the sacred nature of community, on the benefits of community and what it gives that money doesn’t. Because I’m remembering a conversation with one of my former editors, yesterday. She’s got a granddaughter who’s half Korean and who speaks Korean and English. But her mother is British, but she speaks Disney American English because most of the English that she hears comes from the television. And I know so many of my Scottish compatriots who have grandchildren who speak American English, because it’s all coming in on the television. And the language is coming in, and the ideas that language structures, language encodes how we think, are all coming in at the same time. And if we want their minds and their hearts and their sense of spirit to be other than what it is, then we’re going to need, I think, and correct me if I’m wrong, new stories and new ways of seeing the world. First of all, do you think that’s wise? And second, have you an idea of how we could begin to break into mainstream publishing and media, so that the narratives of just even the newspapers and the television, the nightly news, becomes different. Are these conversations that you are hearing in the echelons that you move in at all?

Satish: Yes, that’s a very good question. I would like to see novelists and and storytellers writing the stories about human spirit and the spirit of nature and on a human-nature relationship. The old story is a story of separation. Old story tells you that humans and nature are separate and humans are superior to nature, and therefore nature is only there for the use of humans. This is the old story. The new story which has to be written by our storytellers and novelists and poets and filmmakers and television makers, that new story is a story of relationship. Nature and humans are one. Nature is not just mountains and birds and animals and forests and rivers and oceans. Humans are also nature. We are nature. We are made of earth, air, fire, water. And nature is also made of earth, air, fire, water. And as we are conscious, nature is conscious. As we have soul, nature has soul and spirit. Nature spirit and human spirit, both are spirit. And therefore, this relationship and unity of humans and nature has to be re-established, through our narratives and through our stories and novels and films.

Satish: But newspapers don’t play a good role. Newspapers are only reporting misery and pain and suffering. I think I have stopped reading newspapers. They are miserable and I don’t want to be miserable every day, every morning and every evening. I don’t want to be miserable. Newspapers have to change and they have to start reporting inspiring stories and good stories; how people are doing something good for the world. And that kind of story will be much more useful and helpful than knowing all the murders and all the intrigue and all the political scandals in the Parliament, and the prime ministers, and all the kind of corruption in the kind of EU and all the other war stories. These are creating disaster and bringing more and more misery. Misery creates more misery. And so I want to see a new chapter in our future kind of writing and filmmaking and so on. I want people to be courageous and bring up some inspiring and positive stories and inspiring and positive novels. Like Tolstoy, like Dostoyevsky, like Shakespeare. They had a wonderful way of bringing the balance between negative and positive, but also inspiring. And all the great, great poets of the past; Shelley and Keats and Wordsworth and William Blake and all those wonderful storytellers of the past. I think our future writers have to wake up and do something better than just report misery.

Manda: Definitely. I promise you, some of us are really working on this very hard. And there’s a new A.I. program, Artificial Intelligence, called Chat GPT, which is accessible. And I logged on to it yesterday and I asked it to write me a letter to a newspaper owner, explaining why their newspapers should change exactly from all of the horror to something that wholeheartedly supported the peaceful transition to a regenerative future. And we’re not there yet. We had a very interesting conversation, me and this computer. Because it wrote me a perfectly nice letter. And I said, That’s not good enough. These people don’t care about the planet and about equity. You’re going to have to write something that they care about. And it eventually said, I don’t know how to do that. But I’ve sent it away to learn how to do that, because it’s a self teaching program. And I promised I would come back in a week and it would have learned how to write a letter that, you know, the owner of the Mail or the Telegraph would really get. So I’m hoping that the cleverest computer on the planet can work this one out, because otherwise I don’t know how we reach these people. Besides praying that they reach. But, I think you’re not the only person who’s given up reading the newspapers. The circulation of the mail used to be many millions, and now it’s 820,000. Which is not in the overall scale of things, You know, everybody in politics and the media reads it and a few people outside. So I think their power is waning. So if you were to imagine, let’s take us forward ten years. 2032, almost 2033. If we’re able to shift the world in the way that you would like and the way that you’re talking about, can you paint for us a picture of what the world would look like and feel like and how people would live in a world that is as good as we could get, ten years from now, if we made all good decisions?

Satish: Okay. I would like to see a world by 2050 or 2040, that people work near where they live. So this commuting business, hours and hours driving by car or train or bus commuting, must be reduced and should be reduced. To reduce our pollution and carbon emission. Work where you live or live where you work, that should be the ideal. That’s one thing I would like to see a big change. Number two, I would like to see, as I have already said, every school having a garden, every university having a farm, and all our teachers, professors, lecturers and students working on the land and growing food. And maybe half day you learn academic subjects and half day you’ll learn practical subjects. So there’ll be education of head, education of hearts, education of hands. That will be the education, not just intellectual education. Education in ten or 20 years time, I want to see a new kind of pedagogy, a new paradigm of pedagogy. Where education is not merely intellectual or academic. Education is as importantly practical and head, heart and hands; learning by doing, knowledge with experience. That change I would like to see. And thirdly, I would like to see technology having kind of it’s place and keeping in its place. At the moment, technology is dominating our society and our humanity.

Satish: People are not expected to produce anything. They are not expected to produce food. They are not expected to build houses. They are not expected to make clothes. They are not expected to make furniture. They are not expected to do anything, any work. Work should be done by machine and robots and the computers. So humans are being made redundant, humans are being made useless, unnecessary. And the other thing humans can do is thinking. But artificial intelligence is coming fast and quick and therefore humans don’t need to think! So Humans don’t need to produce and humans don’t need to think. What are we going to do with humans? 8 billion people and more. What are we going to do with them? And so I would like to see certain areas reserved for humans, where no technology is allowed. Such as growing food and building house and making furniture. And then of course, technology can use making technology, like cars and computers and cameras and all that type of thing you can make by machines. And artificial intelligence should be also limited. So human intelligence should be respected and used, because humans hardly use 10% or 20% of their intelligence and 80 to 90% of intelligence is unused. So we must develop imagination and human intelligence and creativity, much more. So that’s in the next 10 to 20 years, I would like to see a change of consciousness where we start to respect the human dignity and not see humans as a kind of obstacle in the progress.

Satish: So reduce the place of human artificial intelligence and reduce the place of the robots and technological interference. And that way, human dignity comes back. At the moment, economy is ruling and humans have become mere resource. Every business has HR, Human Resources. Humans are made redundant when they are not needed. Humans are hired and fired. Humans are kind of used as a kind of means to an end. The end is profit and money. I want to change that in next 20 years. I want to say HR should not be human resources, HR should be human relationship; so that human dignity is at the top and the economy, profit, consumption, production are means to maintain the human dignity and means to maintain integrity of nature. In our modern economic system and technological system, nature has become a resource for the economy, and humans have become a resource for the economy. In the next 20 years I want to change that and I want to say economy should be a resource for human well-being and human dignity and integrity of nature. And profit and production and consumption economy are the means and human and nature are the end. That juxtaposition and that balance need to be restored, and that should be the challenge in the next ten or 20 years.

Manda: That sounds amazing. And then I’m guessing if we have that, then the nature of what we teach our children changes completely, because it seems to me at the moment we’re teaching them to be little robots; we’re teaching them to be the resources in the system and the system is crumbling. So we started at the beginning with you talking about the people in New York who want to set up a small school, like the one that you helped to set up in Devon. If people were to set up small schools all around the world and the children are definitely learning to grow, what is the core of the rest of the curriculum for them? What are they learning? What’s the most important thing for young people to learn? Aside from growing food.

Satish: They need to learn two things. Number one, that nature is our teacher. Nature is not just to learn about, but nature is to learn from. That’s one change I want to see, that nature is something that we should learn from and not learn about. Number two, I want our children to be more skilful. Skilful in terms of using their hands and being able to make something. Humans are not mere consumers. We are makers. Humans are artists. Humans are poets. Humans are makers. So I want to see that change; that we maintain the quality of making rather than just consuming. So that’s another important change that I want to see in our education. And that’s the kind of idea of the small school. The small school was about learning from nature and learning to be skilful. To be able to make things, build a house, make furniture, make poetry; be an artist, be a poet, and not just a consumer. That was the idea of the small school and I want to see that kind of educational system coming back.

Satish: At the moment, our education is not education. It’s just a kind of training to go and work in a kind of system. So education is part of the problem today. Today’s education is not part of the solution. All the great problems we face today are created by highly educated people at Harvard, at Yale, at Cambridge, at Oxford, and all the other big, big universities of Paris, Moscow, Beijing, Delhi, wherever you are. And so educated people are part of the problem. They are causing the wars, they are causing the climate change and global warming. They are causing the kind of pollution and waste. The economy is run by educated people. The war industry, the machines. The Ukraine was created by highly educated people from both sides. And therefore we need to have education, which is education of a spirit as well as education of intellect. Education of imagination, as well as academic education. So that is my ideal. I’m a dreamer, but as John Lennon said, I’m not the only one. I’m a dreamer and I want to imagine that we can create a new world.

Manda: Fantastic. That feels to me a really good place to end.

Satish: Good.

Manda: Except I wonder… I know that you do a meditation on a Wednesday morning for the people at the Oxford Real Farming Conference, and I wondered if you would feel able or like to do a meditation for us now? So this will be going out on the Wednesday, the week before the conference. So that people could have a sense of what you lead. And if you don’t want to, that’s completely fine.

Satish: Okay, let us have a short meditation.

Manda: Okay.

Satish: Right hand represents the world. Left hand represent the self. By bringing both hands together, we bring the world and the self together and we bow to the sacred life. Sacred universe, sacred earth, sacred soil. Then we breathe in, breathe out, smile, relax and let go. Let go of any expectations, any anxiety, any fear, any anger. Breathe in, breathe out, smile, relax and let go. Feel that the whole cosmos is our country and feel that the whole planet Earth is our home. Feel that nature is our nationality and feel that love is our religion. Breathe in, breathe out, smile, relax and let go. Let go of any sense of separation, any sense of ego. We move from ego to eco: We are all interconnected, interdependent, interbeings. Breathe in, breathe out, smile.relax and let go. Let the unity and diversity of life dance together. Breathe in, breathe out, smile, relax and let go and bow to sacred life, sacred art, sacred universe. Sacred in all and every living beings. Thank you.

Manda: Satish, It’s been an honour and a privilege. Thank you so much for sharing this hour’s conversation. I hope that the Oxford conference goes well.

Satish: My pleasure. Thank you for your time.

Manda: And that’s it for another week. With enormous thanks to Satish for his generosity of spirit, his vision and his capacity to speak with such honesty and clarity about the nature of the world and how we can shift it. The Oxford Real Farming Conference starts next week if you’re listening to this at the time it goes out; 4th to the 6th of January. And whereas, I believe pretty much all of the in-person tickets will have gone by the time you hear this. There are, of course, still online tickets available. So do head over to orfc.org.uk and get your free tickets there and come along and explore the absolute wonder of so many amazing, dedicated, knowledgeable, thoughtful, creative and compassionate people who are going to be speaking there.

You may also like these recent podcasts

ReWilding our Water: From Rain to River to Sewer and back with Tim Smedley, author of The Last Drop

How close are we to the edge of Zero Day when no water comes out of the taps? Scarily close. But Tim Smedley has a whole host of ways we can restore our water cycles.

This is how we build the future: Teaching Regenerative Economics at all levels with Jennifer Brandsberg-Engelmann

How do we let go of the sense of scarcity, separation and powerlessness that defines the ways we live, care and do business together? How can we best equip our young people for the world that is coming – which is so, so different from the future we grew up believing was possible?

Brilliant Minds: BONUS podcast with Kate Raworth, Indy Johar & James Lock at the Festival of Debate

We are honoured to bring to Accidental Gods, a recording of three of our generation’s leading thinkers in conversation at the Festival of Debate in Sheffield, hosted by Opus.

This is an unflinching conversation, but it’s absolutely at the cutting edge of imagineering: this lays out where we’re at and what we need to do, but it also gives us roadmaps to get there: It’s genuinely Thrutopian, not only in the ideas as laid out, but the emotional literacy of the approach to the wicked problems of our time.

Now we have to make it happen.

Farm as Church, Land as Lover: Community. farming and food with Abel Pearson of Glasbren

The only way through the crises we’re facing is to rekindle a deep, abiding respect for ourselves, each other and the living web of life. So how do we make this happen?

STAY IN TOUCH

For a regular supply of ideas about humanity's next evolutionary step, insights into the thinking behind some of the podcasts, early updates on the guests we'll be having on the show - AND a free Water visualisation that will guide you through a deep immersion in water connection...sign up here.

(NB: This is a free newsletter - it's not joining up to the Membership! That's a nice, subtle pink button on the 'Join Us' page...)