#198 Healthy Human Culture: Diving deep into ourselves, each other and the world, with Sophy Banks

How do good people create systems of oppression? What is Health? What is unHealth? And how do we move from the latter to the former in ways that mean good people create systems of co-creation, inter-being and connection? This week, we explore all these questions with Sophy Banks, Founder and Lead Facilitator of Healthy Human Culture.

This week’s guest is a remarkable woman who was one of the shining lights amongst those who came to teach us at Schumacher college, before the pandemic Sophy Banks has been an engineer, a footballer, and a therapist. She was deeply involved in the Transition movement from its inception, finding ways to balance inner and outer work, to keep heart-focused in a world where a lot of outward-focused action can so easily lead to burnout.

I met Sophy as she was moving away from that role, moving into Inner Transition as a new movement and also working deeply with Grief Tending workshops inspired by her time with Sobonfu and Patrice Malidoma Some from Burkino Faso. That was back in 2017 and clearly the world has moved on since then and Sophy has moved with it.

She is now Founder and Lead Facilitator of the Healthy Human Culture movement where she brings together the deep learning and experience of the past decades in a system of online learning journeys and other workshops which offers a vision for a world in which societies, communities, workplaces, families and individuals can thrive. It’s a journey of healing and understanding and exploration and it feels absolutely core to where we are going, could go, need to go as people and as a culture. It is always an honour, a delight, and a deeply thought-provoking, moving experience to talk with and learn from Sophy. I hope you enjoy this as much as I did.

In Conversation

Manda: Hey people, welcome to Accidental Gods. To the podcast where we believe that another world is still possible and that if we all work together, there is time to create the future that we would be proud to leave to the generations that come after us. I’m Manda Scott your host in this journey into possibility. And this week’s guest is a remarkable woman who is one of the shining lights amongst those who came to teach us at Schumacher College in the days before the pandemic. Sophy Banks has been an engineer, a footballer and a therapist. She was intimately involved in the transition movement from its inception, helping to find ways to balance inner and outer work, for people to keep heart focussed in a world where a lot of outward focussed action can so easily lead to burnout. As I said, I met Sophy in 2016 as she was beginning to move away from that role and moving towards inner transition as a new movement, and also working deeply with grief tending workshops inspired by her time with Sobonfu and Malidoma Patrice Somé from Burkina Faso. They were some of the most transformative experiences of my life. And whatever other healing you have in your life, I can completely attest to the fact that a grief tending workshop, probably several, is really transformative. Sophy is still leading those and I will put a link in the show notes. But she is also now founder and lead facilitator of the Healthy Human Culture movement, where she brings together the deep learning and experience of the past decades in a system of online learning journeys and other workshops, which offers a vision for a world in which societies, communities, workplaces, families and individuals can thrive.

Manda: And doesn’t that sound exactly what Accidental Gods is here to promote? The healthy human culture offers a journey of healing and understanding and exploration of self and other, and it feels absolutely core to where we’re going, where we could go, where we need to go as people, as a culture, as an entire world. It is an honour and a delight and always a deeply moving experience to spend time with Sophy. So people of the podcast, please do welcome Sophy Banks of Healthy Human Culture.

Manda: Sophy Banks, welcome to the Accidental Gods podcast. It is such a pleasure to be talking to you again. I will say this now, I will probably have said it in the intro, that you were one of my greatest inspirations when I did the Masters at Schumacher. And everything you’ve done since seems to be growing in the directions that we really need. So you’re developing the healthy human culture body of work, concept, courses, and we’re going to explore that today. So just to start off, how are you and where are you? And then tell us a little bit about how this came to be your focus, because when I knew you last, you were doing a lot of really deep work on death and grief and this feels like a slightly new pathway perhaps or at least a deepening in other directions. So over to you.

Sophy: Really lovely to be here. Yeah, I’m in Devon, so not far from Schumacher, surrounded by the fruiting garden that I live in and an abundance of plums and figs at the moment, which is just a very deep joy.

Manda: Wow. Yeah, I have Devon Envy. Just as a separate, completely farming concept, most of our fruit seems to just really not be setting very well this year, because the weather’s been so weird. It’s okay in Devon?

Sophy: Last year we had the most astonishing bumper apple crop, so I feel like all my apple trees are just taking a rest.

Manda: Okay. Right. Yes, that’s probably true. Anyway, back to healthy human culture. Tell us a little bit about what it is and how you came to be doing this and doing it now.

Sophy: In some ways I feel like Healthy Human Culture is the accumulation of all of the questions that I’ve held and the inquiries and the different bits of learning that I’ve accumulated over my life. So. My family of asking, you know, why is this family of good people and good intentions so complicated and creating actually quite a lot of fear and suffering in its children, when there absolutely wasn’t the intention of my parents, good people.

Manda: Right. Yes. And isn’t that so often the case that that parents I watch so many of my friends who are parents and they are really good people doing their very best and and and we’re all watching the kids being screwed up in real time. And it’s cultural and it’s inherited and it’s not knowing what else to do. I would say. Sorry, I didn’t mean to interrupt.

Sophy: And I think there was a second sort of layer for me in my 20s that was coming out into the world of being a lesbian, playing football, being around very working class women, women of colour, Irish women, and waking up to systems of oppression. You know, this was in the 1980s. So Irish politics much more hot and present in the UK. So I feel like there was a whole sort of waking up to white middle class privilege and how different lives were for people of colour, for people with working class backgrounds. And I was an engineer at that point. So learning hard science, technology, you know, probably thinking as was the sort of belief system of my family and my culture, you know, that science had a lot of the answers. And as I was heading for my second break down, I would say around the age of 30 and the failure of my relationship that I thought would last forever, I started to turn towards inner work. I slightly accidentally became a therapist, you know, but I was on my own sort of therapy journey and started to meet ideas around unconscious. It wasn’t framed as trauma in those days, but this sense that there are parts of us that are out of awareness, that are running quite a lot of our behaviour and it takes work and support to bring those parts into awareness. So when we’re doing inner work we start to have more choice. We start to bring those parts of us that are out of awareness into conscious presence. And as we do that, we have more choice about which part of us we go with, or which part of us is present and in charge. In charge of what’s happening.

Manda: Okay. All right. I have a question on that, definitely. But go on.

Sophy: And then the last piece in terms of bringing Healthy Human Culture into existence was my time in the transition movement, where I felt like my role was to hold a focus on inner and depth and systemic dynamics, but also to bring the kind of wisdom from many different inner traditions; spiritual, psychological, earth based, ceremonial, you know, peacemaking, the many, many threads of inner work. And weave that into a movement that had a tendency often to be out of focus. That came through quite a strong window of permaculture, which had its own dynamic about inner and outer. And in that I found that I was constantly on the edge of burnout. I felt like the people focussed on outer and action and doing, tended to polarise from people that were focussed on being and depth and inner and process and relationship. And I got very curious about that polarisation. And that was happening for me at the centre of the movement within Transition Network. And I believe that the dynamics that come and the challenges that come at the centre of the movement have meaning for the movement, in terms of its purpose. So I felt like I was in a deep inquiry about that and about burnout.

Sophy: What did it mean that maybe a third of the people in transition were burning out? In a movement that was, you know, one way of saying it would be intending to prevent the planet from burning out. What had we not understood about burnout that we needed to understand, to deepen and to really serve our mission? So it was in that context that the ideas of healthy human culture really started to take shape. And to link them, I would say one of the things that I saw when I started to draw maps, because really I’m an engineer underneath all of this inner work. Is that the the response to pain and the relationship to pain and grief is really central to whether we create healthy culture or whether we create a culture where that pain is avoided, passed on, put into other bodies, turn towards the earth. What we do with our pain is really central to whether we create healthy culture. So for me, like you’re saying, grief tending, shared spaces of tending our grief in all its forms, and this map of healthy human culture, feel very interwoven for me.

Manda: Beautiful.

Sophy: So I’m holding both at the moment, you know, they’re both part of my work.

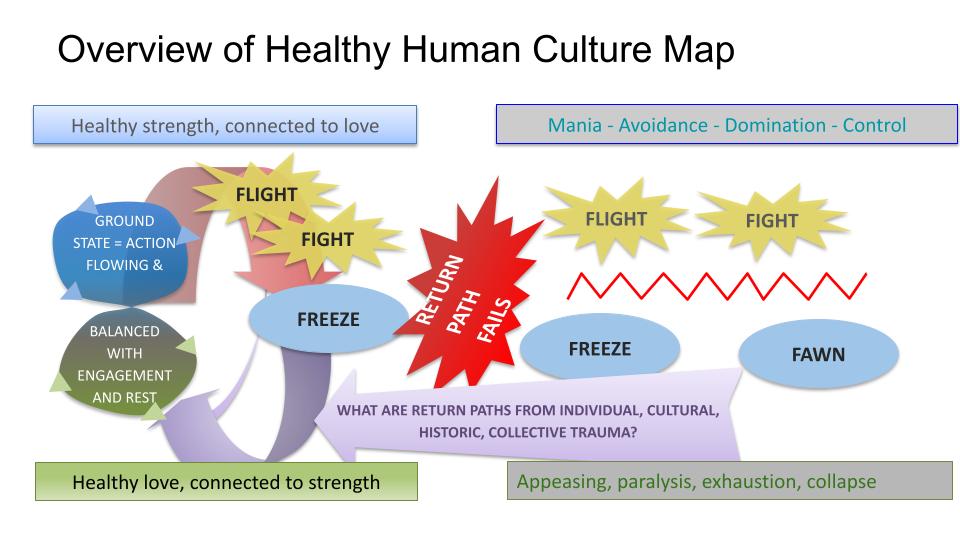

Manda: Brilliant. Thank you. There are so many questions in that. I have a question on how an engineer accidentally becomes a therapist. But that’s that’s too process led. Let’s not go there. I would love to talk more about football as well, given we’re recording this, People, at the end of August. So football’s been in the news quite a lot. However, let’s not. So you have a map which we will get a copy of and put that up on the website. Guys, you can find it at accidentalgods.life/podcast. Can you talk us through how the map works? Because a map is not the territory, but it seems to me, having seen a little bit of your map, that it does map a territory very well. And it’s an inner territory of ourselves and it’s a territory of the culture and the systems that we live in. So this is applicable on many scales. Let’s have a look at it and see if we can begin to unpick how it applies to each of us individually and how it applies to the world that we live in.

Sophy: In my mind, I’m imagining the map in front of me and I start on the left hand side of the map. And the left hand side of the map is exploring the question What is health? What is health for human beings? And as you say, for human beings as individuals, but especially for human beings in relationship, in groups, in society. And I guess the intention of the map was to put together these individual insights that I’d learned from therapy, from my life experience, but especially to put that together with systems of power and oppression. And also why are we destroying the planet? You know, the question of the day or a question of the day. And one of the things, one of the pieces that I started putting together in the transition movement, was this polarising of being and doing. With archetypes that I’d met in my psychosynthesis training, where a definition of a healthy human is someone that has a developed capacity for love and a developed capacity for will. And I spoke to somebody that I met through my transition work, who was a Chinese medicine practitioner, and asked him about health in the Chinese system.

Sophy: And he said the first sort of framing of health in Chinese medicine is the balance of yin and yang. So we had these two archetypes again. And I was really looking at trauma; there was a lot more about the neuroscience of trauma. Peter Levine’s work was coming out when I was in this inquiry. And I started to wonder whether these archetypes of health had something to do with the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems and the sense that healthy human beings have their sympathetic and parasympathetic working in right relationship, in a state of relaxation, in a place of trust in our relationships. Of attachment, because attachment is so central to what it is to be a human being. And then I started seeing these pairs of relationships in other systems. I was working with Sobonfu Somé. In her culture, it’s the balance of fire and water. It’s the important thing. Three times as much water as fire, really wary about fire.

Manda: That’s from Burkina Faso, yes?

Sophy: So Sobonfu and Malidoma, who came from the Dagara people of Burkina Faso, brought their teachings to the West, seeing that, you know, we were destroying ourselves and also soon would be destroying their culture. Obviously, much of African culture has already been destroyed. And I heard Woman Stands Shining Pat McCabe; she was talking about it as gender masculine and feminine, needing to be in right relationship. I tend to not gender these archetypes. I think it’s really helpful to keep gender out of it.

Manda: Yeah, really. Okay. But we’ve got yin and yang and fire and water, which we definitely can work with. And sympathetic nervous system and parasympathetic nervous system. Let’s have a little bit more of a look into those because they can become very stylised quite quickly. We can end up with shorthands of fight and flight and and then get lost in Polyvagal syndrome and all of those things. And what I am understanding from your map is much more of how in a healthy human or a healthy culture, there is flow and balance between all the different aspects of each of those. They are complex things in and of themselves, and that if we render them static in our own concepts, then we are going to end up bouncing back and forth between the yin and the yang or the fire and the water, instead of flowing between them. So can we dive a little bit more deeply into those?

Sophy: I’m curious that the sympathetic nervous system is so associated with fight and flight. And when I’ve listened to people who really work in detail with nervous system states, it’s actually just a mobilising system. So just to stand up, I need a bit more sympathetic activation to give a bit more blood pressure, a bit more oxygen. Just to go for a walk. I need a bit more sympathetic activation, you know, to go to sleep, to wake up, to be more active, to dance, to hug somebody.

Manda: Play football.

Sophy: To play football. So I feel like part of healthy human culture is reclaiming the sympathetic nervous system, as a joyful, stress free, mobilising, active. You know, part of the joy of life is to be in our sympathetic, moving through the world alone together in relationship. I think it’s a good question and I’ve asked groups of people, how often do they feel they’re in a kind of active state without stress? With an underlying sense of capacity, of trust, of resource. And actually for a lot of people, especially working in mainstream organisations, that’s a really rare state actually. So much of our activity has stress, pressure, push, drive associated with it. So the first part of healthy human culture is the movement and flow between action and rest, between outward and inward, between new experiences that stretch us, that bring us learning, that develop our bodies, that develop our relational capacities and the digestion, the integration, the recovery. The soothing that allows our bodies to fully integrate and experience and then be ready for the next one. And what I see in healthy cultures, healthy organisations, when I’m in health in my own life, is that there are practices, rhythms, habits, rituals, you know, which could be as simple as how do we end our day together? We’ve gone out, we’ve done stuff in the day and how do we digest our day? Do we sit and talk about it? Do we write in a journal? Do we go for a walk? Do we have a bath? Like, what do we do? Or is our evening still super pressured? And then I fall asleep, exhausted and get up the next day and have to go, go, go again.

Sophy: And if we’re doing that, what’s that doing to our bodies, to our immune system, to our nervous system? So this is the first bit of healthy human culture. Like a ground state of flow between action and rest, and with movements into stretch, whether that’s relational stress, you know, learning how to be with each other and the pressure of getting on with each other. I think getting on with other humans is the hardest technology that we need to learn. But it could be physical, you know, project management, something new, a new skill, something that I’m learning with my body, with my mind, with my emotions. And then recovery, digestion, integration, that’s the basic pattern of healthy culture. And then shit happens, you know, disaster, accidents, disruption, conflict. These things happen and our autonomous nervous system takes us to flight, then fight, then freeze. Now we’re into polyvagal theory. And then the key thing about healthy culture is, is there a return path? Especially once we get to freeze. But once we’ve got to flight or fight and there’s a significant activation, how do we come back? And if there’s a rupture in our relationships, how do we repair those? How do we come back to this ground state, where we’re fundamentally feeling a sense of trust and holding in my self, in my relationships with humans and in the wider holding of life?

Manda: So can we delve more deeply into return paths then? Because that seems to me to be really core to the concept of healthy human culture. And also in so far as I understand it, it feels like one of the absolute missing keys. Let’s assume that healthy human culture is our birthright, that we evolved for hundreds of thousands of years with really healthy human cultures, we assume. Certainly looking at other indigenous peoples insofar as they survive around the world, they have some really healthy cultures and in those cultures relating with other people seems not to be so traumatising and fraught with difficulty as it is in ours. And using your map as a model of their landscape, it seems to me that the rituals and the return paths and the ways of heading trauma off at the pass, that’s probably not the right paradigm, but they have ways of not getting as stuck as we do. And that it’s the return paths and the rituals that might be making the difference. If I’ve misunderstood that, please feel free to correct me. But if not, can we delve into what is a return path and how do we recognise one?

Sophy: I am deeply curious about what they might be or have been in cultures that have endured for a long time in relatively peaceful, relatively joyful, relatively respectful ways. So some of the examples I’ve come across in Sobonfu and Malidoma’s village in Burkina Faso, they would have a grief ceremony every week. And that grief ceremony would involve drumming and dancing and singing. It would involve somebody going to the shrine with support, expressing whatever was there to be expressed. So it’s physical, it’s emotional, it’s rhythmic. You know, a lot of the things that we in the West have learned much more recently about how to move stress through the body with support are built into the structure of that ritual or ceremony.

Manda: And have you experienced this on a weekly basis? Because I have done grief ceremony with you and it was an extraordinarily moving event that had ripple effects through my life probably forever. But certainly I was aware of it as a physical thing for weeks. The idea of doing that weekly is actually quite scary. But I’m guessing if you do it weekly, it’s probably not such a huge cataclysmic event each time. Because your bucket is never quite as full, I’ve just moved into dog training metaphors, but is it as big every week or is it something that the mountain to climb is not quite so huge?

Sophy: I don’t know. Is it every week? I don’t know the details of exactly how often, but it was seen as part of the kind of emotional hygiene of the village. And it would be expected that you would attend, you know, maybe not every week, but at least from time to time. And if you weren’t going, this is what I understood from Sobonfu, you know, somebody would come and say, Hey, why aren’t you showing up? You know, why aren’t you doing your work to keep the the village space clear? And I don’t want to romanticise or idealise. You know, I think that culture has its shadow and it’s places that were not in health. But the sense that I had meeting Sobonfu especially, was of somebody who felt absolutely at home in her body. A sense of self-worth and self-confidence that I rarely have found in myself or met in other women, especially, who had grown up in modern Western culture. So another example was Rob Hopkins interviewed one of the grandmothers at Standing Rock. And I’m sorry that I don’t have her name. And asked, you know what do you do when the young people, the young men, the others, the young women come back from the front line, you know, how do you help them to come back and deal with the shock and the violence of being tear gassed or water cannoned by the police? And she said, we put them in a sweat lodge.

Sophy: You know, we take them to the sweat lodge. Like, okay, that’s another return path for processing shock and violence through the body. I’ve heard of the San people, the Bushmen in the Kalahari doing ecstatic trance dances. So for me, this sense that there are many ways, there are many possibilities and they involve ceremony, they involve physicality, they involve support, the opportunity for vocal expression, you know. So I imagine there are many of them. And I feel like in the in the West, in modern culture, we’re starting to see the importance of somatic, of including the body, of shaking out, of release. I feel like we’ve gone from very heady therapy, psychoanalysis, you know, to much more including the feelings. With humanistic therapies, gestalt, psychosynthesis, what I do. And now I feel, you know, good therapy trainings are including the somatic level. And for a lot of people who evolved their culture as they evolved into life, into being, that was woven in, that was just a part of what they did.

Manda: Right. And and we have things like five rhythms dancing and everything that’s evolved from that. And my limited experience of that is that things move on levels that are so far removed from my conscious awareness. The energy in the room becomes a living thing and something with which one relates as much as with the other people. And I imagine and without wanting to romanticise, as you said, that if you have done that with with your tribe from before you were born, that in itself becomes a whole – technology is the wrong word – but a whole system of of healing and connecting and knowing and liberation, that does seem to be one of the key features of indigenous peoples. I’ve just finished reading Civilised to Death by Christopher Ryan. And he has a lot of instances of recordings of older cultures that are no longer with us, or people who are still in indigenous cultures. And what seems to be absolutely key to the way that they live is a sense of personal freedom and a sense of inner joy. Exactly what you said. One of the researchers who stayed with a tribe in the Amazon whose name I will never remember, but he said, Why do you think I’m here? He’d been with them for 5 or 6 years. And they said, because we’re happy and we’re really good people.

Manda: And and yes, that was exactly it. He wrote that they laugh all the time. They laugh when a tree falls on their hut or they laugh when the sun rises or they laugh when a child is born or they laugh when somebody dies. And it’s not a it’s not a defensive laugh as we would have. It’s this is life and life is amazing. And we must, I’m thinking, this is taking us a little bit off, but it has seemed to me for a long time that we have a million years probably of human evolution. Something else I learned from the book is that our are relatively blunt teeth and short guts mean we have been cooking food for a million years. And it’s only really in the last 10,000 that things have begun to fall apart and at least certain of our cultures became hierarchical and dominant and distracted and disconnected and ruptured and traumatised. And that’s a tiny part of our overall evolution. And therefore, if we can find ways to heal the trauma, our natural state is to be connected with ourselves and each other. And it can’t be impossible, I hope. Anyway, sorry. Rant. So return paths require ritual. Do they always require movement and dance and song? Or are you aware of other return paths that are happening in the flow of our daily lives?

Sophy: I think a return path could be something as simple as stopping and taking a breath. You know, that could be a micro return path, you know, sitting and meditating and letting or just sitting and watching the sun set and letting my nervous system recover. Is that a return path? You know, it depends what we mean by it, but I like the idea that we need to build in these sort of micro rhythms of returning, of soothing, of recovering, of digesting. At every level of scale, you know; interpersonal, personal, societal, as well as across time. I think the truth and reconciliation process in South Africa was an attempt at a return path of repairing the trauma of apartheid. Imperfect, brave, but also did some extraordinary things. What the return paths look like as cultural systems? It might look like restorative justice rather than criminal justice. It might look like teaching children conflict resolution skills, you know, restorative skills, emotional repair skills. Simply how to apologise and repair relationships, as part of the curriculum. Many people have been trying to get that kind of learning, skill space into schools. And because we’re starting to use the word trauma, I want us to start to speak about the next sort of area of the map. The middle of the map, if you like. Is what goes wrong? What takes us away from what I believe is a kind of expectation, a birthright; when something happens that is painful, that is threatening, that takes me into a sense of survival threat.

Sophy: I think we expect that there will be a return path. I think we expect that our people, our community, our parents, our elders will know how to bring us back. Will feel that we’re of value and worth bringing back, will notice that we’re not okay and that there will be some process to bring us back. So I’ve started to look at trauma as not just an overwhelming event, because I think overwhelming events with a sweat lodge, with a grief ceremony, with a restorative justice process actually teach us something completely different. They teach us that together we can endure shocks and ruptures and repair them. They absolutely build resilience into our communities and into our relationships. And so the thing that creates trauma is not the shock of violent conflict, it’s the failure of a return path. So trauma is a two stage process. And possibly a third stage, which is why did it happen in the first place and how are we attending to that? But, you know, one of my early areas of exploration as a therapist was around sexual abuse. And I met people who’d been working with sexual abuse a lot who said it’s not the abuse so much as what happens when the person abused tries to speak about it, if they are listened to. If both the person abused and the abuser get help, if the system is brought back into health, actually there can be a repair that is not permanently damaging.

Sophy: It still is impactful, but there’s not a permanent rupture to a sense of safety in the world. What really creates the lasting impact is when that person isn’t listened to, when the perpetrator is still abusing, when the system of denial closes in. That’s one example. But across any example, that second stage of the failure to attend to and repair, I think creates a second layer of shock and leads to a very profound sense of rupture, and a belief that I can’t cope with what happens. We can’t cope with what happens. When shit happens, life does not support me. And that goes forwards for individuals. But in a culture that has lost its return paths, that starts to be a pervading underlying belief: we cannot cope with our pain. When there is violence, we cannot recover to rebuild the web of trust with each other and with the people on the other side. Life now becomes a threatening, unsafe place to exist. And then we start to create individual and collective strategies for managing life where we don’t actually face into the pain head on, because we don’t believe we have the capacity to do that. And I think that’s the underlying sort of landscape of our present culture. And that’s why grief tending, why turning towards pain, why making places where we look at pain collectively is a really essential component of what’s needed.

Manda: Gosh, there is so much in there. So let me just gather what I think I’ve heard. So essentially gaslighting, which is the ‘there was no problem, nothing bad happened’, is the toxic overlay to whatever the difficult thing was. And it’s so toxic because we are born, I think I heard you say, with an with an innate expectation, belief, understanding, that the world is a safe place and that we will be held. And that if something bad happens, there will be ways to heal it. And then something bad happens and that expectation is completely not met. And it’s the combination of bad stuff and the not meeting that creates the really deep trauma. And clearly, one can see that on so many individual levels. I’m just thinking about the whole Spanish footballing paradigm event and wondering then how that could have been managed differently. Let’s not go there. It’s too deep and too difficult. And by the time this goes out, it’ll have been yesterday’s news. But it seems to me, how do we bring this to a societal level? Because what you’ve just described, we can see it going on in every newspaper headline every single day. In all of the toxic Twitter threads. Our politics is designed to perpetuate this trauma.

Manda: Gaslighting is what politicians do. You know, we’re going to dump sewage in the rivers and then tell you that it’s completely not a problem. And in fact, we’re going to change the rules so that totally toxifying every river in the country is fine. And on other threads that I’m on, watching people finally breaking. People who’ve been working against an individual water company throwing sewage in the river, and they’ve been working against this for years and now things are breaking. They are breaking. Because the system seems so obviously stacked against us. And that on every level, in every field, this is happening. And it feels to me as if we’re back to why did good people create toxic systems? And you’re very good and you believe they’re good. And I look at them and I think they’re inherently evil. And that’s probably because I’m not a trained therapist and I just think these people are just bad. But let’s go with your view of they’re good people and they’re creating toxic systems. How do we change the system so that we have the return paths, so that this isn’t the way life is?

Sophy: I’d like to just spend a little bit more time in a way in the middle of the map and then come to that question. So I think I think this question of why or what’s happening, it’s useful to ask that question and I think internal family systems is really interesting. I came across a guy called France Rupert, who was a family constellata, very, very interested in trauma. He was a medical doctor, but also a family constellata and he came up with a model around trauma, that said when trauma happens there are three parts that go forward. One part is the traumatised part, which carries on as if the trauma, as if this moment of overwhelm and terror and helplessness and threat is happening in the present moment. So there’s a part of us that is carrying that, which is split off, you know, pushed out of awareness, this extraordinary capacity that humans have to repress that in order to survive in the moment. So that part, it continues to exist, if you like, waiting for the repair, waiting for healing. The second part that goes forward is the survival part. A very healthy, useful, evolved response to situations of overwhelm, that strategizes or manages or engages with the world as it finds it, in order to survive in a moment, which may become a very long moment, where there is not the resource to deal with the overwhelming situation. And the third part that he points to, which is really important to keep remembering, is ‘And there is still health’.

Sophy: So most people, I would say in every society, probably have a mix of some experiences of repair. And the attachment holds and there is holding and life is good and there is joy and confidence and value and and so on, safety. And experiences when that didn’t happen. And we know the other side. So to see this individually, in internal family systems, I think there’s the exile, isn’t it? It’s like the traumatised part. And then you have a manager or a firefighter,that are very much the kind of survival parts in France Rupert’s models. But this sense that there are parts of us that are dealing with life in a world in which there is not always the opportunity to heal. Those parts will have residue of the emergency nervous system states. So there will be a lot of fight, there will be a lot of flight, there will be a lot of freeze and fawn and the other ways that our bodies evolved to try to cope with situations of stress. And I think it’s helpful to see those as cultural patterns. You know, you talked about gaslighting and denial. That’s one response. Another is persecution, is a more fight response, to go, we’ll attack the victims, we’ll blame the women, we’ll shoot the black people. That’s another way of surviving in a world that’s fundamentally unsafe. Another is to appease. Another is I don’t have enough power, so I’ll just do whatever is asked of me. I’ll give up my sense of self-worth. I won’t set boundaries.

Sophy: So we can see those patterns and if you take any issue, whether it is ecological climate change, whether it is racism and post colonialism, white supremacy or gender violence, you can see I think all of those behaviours as systemic patterns of behaviour. And I think it’s helpful to acknowledge that they’re distributed all the way through the system. So if I’m really honest, I can find the part of me that uses my power sometimes to dominate and get my way. I can find the part of me that avoids and denies. I can find the part of me that appeases. The part of me that just numbs out and shuts down. And so I think it’s helpful to acknowledge that all of those parts are in all of us and in every bit of the system at all levels of scale. And instead of asking, is this healthy or not, it’s more helpful to ask what’s healthy? Where’s the health in this system? How do I experience it? And where is there not health? You know, how is that operating in me and my relationships, in my organisation, in my family, whatever. And I may identify with a place of more strength or with a place of more vulnerability, but the split is always in me. So if I identify more, you know, in my family I feel like I took the role of the one who was more persecuted and carried more of the pain. But I’ve still got the part of me that actually wants to kill people. And those two parts are connected.

Sophy: So then we start to see the right hand side of the map, which is the part where trauma has occurred. There are not return paths. And now we have these split off behaviours operating in complex ways throughout the system. And so on the top, what I put on the top side, is the kind of more sympathetic responses. So fight and flight, so systems of domination, but also avoidance, denial. I think addictions come into that. So I can’t cope with things, I’m just going to escape. And those patterns are often associated with privilege, you know, where there are systems of privilege and marginalisation. The option, the choice that some people have to just walk away from dynamics around race or gender or class or disability, to ignore it as if it’s not a problem. And then on the bottom right are more of the behaviours that are around appeasing, a sense of powerlessness. And I want to make this really important distinction between these behaviours as structures and patterns of behaviour that I can find in myself and a lived reality that is created when this right hand side acts out through systematic violence, through creating poverty, through taking resources and Land, through destruction of culture. Where there’s genuine powerlessness, you know, where there is a lived experience of scarcity. And really important to keep distinguishing between what are structures, psychological structures or emotional structures, and what is a lived experience of violenc? As perpetrator, as the one receiving it, the target.

Manda: Right

Sophy: One more piece, which I think is interesting, is what I have experienced, and this brings me back to the kind of split between doing and being in transition. Is that if we don’t have a health of doing, if we don’t have a health of action, we’re on the right hand side of the map, where action is in denial of vulnerability, where where action is often fear driven. So looking at activism, which I think is itself a really interesting word, activism not being ism. You know, we’ve already gone a bit too top right, driven by a sense of urgency or scarcity or fear, says we don’t have time to do the inner work. We don’t have time to focus on relationships. You know, we don’t have time to feel the feelings. We just got to do, rebuild, do the action, stop the damage, whatever it is. And now there becomes this kind of split between outer and inner, between action and feeling between mind and body.

Sophy: And I think part of how I’ve come to understand that is that those that have the option to identify with strength, or those parts that identify with strength on the right hand side, don’t want to stop and feel because underneath is this layer of trauma. And if we sit on the cushion, you know, if we stop and really start to go into what’s happening in my body, what’s the constriction of my breath, what feelings are down here? We’re going to meet that place and I’m going to be catapulted back into a sense of powerlessness and terror that is in the traumatised part, waiting for attention. And as soon as we start to approach that, all of the fear that’s in there starts to surface and say if you touch this you may never come out. It goes on forever. There’s not the resource to deal with it. So then we get this split between outer and inner, that kind of perpetuates a system where we don’t heal, where healing is not the focus and the priority.

Sophy: And I’ve met so many people involved in actions and projects for positive change where this split and the people who are more process oriented are often feeling hopeless in the face of action people, who will not attend to relationships and the deeper work and the healing that’s needed. And projects end up in conflict or burnout, you know, which you can see as being the consequence of flight or fight, isn’t it? We end up in conflict or exhaustion because we’re not tending to vulnerability. We’re not willing to do that healing work. And I can see why. If you’ve never had the experience of that being met and held, of course it’s terrifying.

Manda: Right. And that sense that if you take the lid off the can of worms, you will never get it back on again. I meet that so often with people. I can’t do that, exactly as you said, there is no route to healing and it’s not possible and therefore we mustn’t try. We must just exactly as you said, get out there and do stuff with a sense of terrible urgency. So clearly you’ve created the course, The Healthy Human Culture course to help individual people to address this. And we don’t want to tell people exactly what’s on the course, because we want people to do the course. And it seems to me, it feels this is one of those things where if everybody did this course, the world would become a different place simply because of the resourcing that would be there. Absent of that, do you have a sense of any other route to healing our culture? Or is it person by person working through their own trauma and coming to a place where they feel resourced, where they have the return routes? On a daily basis. Is that it?

Sophy: I think there are many, many pathways. I like to speak about an ecology of systems and interventions. I think there are, countless, countless ways to heal parts of the system. Hillary Prentice used to talk about the kind of earth based wisdom traditions, things that come from indigenous people that haven’t lost or have managed to hold on to some parts of their practices for healing, for repair. Some things that come more from the modern sort of Western tradition of psychological understanding, which, you know, has been evolving and developing. I think it’s so interesting that we’re getting much quicker at healing trauma, individual trauma and collective trauma. And then there’s the kind of, Hillary used to speak about it as the more eastern sort of meditative and transpersonal ways of creating healing; Chinese medicine, Buddhism. Ways of understanding mind and consciousness. And so that’s one way of describing three kind of huge rivers of insight, tradition practices, knowledge, pathways. And we can expand that to all the people doing conflict resolution work, peacemaking work, all the different kinds of activism. And none of it will be perfect. A healthy human culture isn’t going to be perfect. It’s going to have its shadow. It’s going to have its unhealth, its unconsciousness. None of them will be the immaculate solution.

Sophy: But every part of the ecology is important and valuable. To the extent that people have choice or freedom to be able to access these, which itself, as we know is very determined by privilege; which pathway suits you, what interventions help your organisation or your group or your relationship depends on you and what works for you. We have a richness of pathways and people exploring and discovering and passing on. I feel like people like Thomas Hubl, Gabor Mate, Resmaa Menakem, are really putting together individual somatic practices with collective healing, with addressing collective trauma. Some people are going from the individual; Richard Schwartz, who brought in internal family systems, very much started working with individuals and now starting to apply that much more, starting to be much more in a conversation about collective trauma. Gabor Mate has done the same journey, I would say. Others like Thomas Hubl, much more starting from a collective perspective. What is the we, what’s the collective dynamics? And I think that’s a really helpful, interesting meeting. And it feels interesting, as the crisis deepens, that these movements of evolution of what healing is and pathways and understandings around healing are also happening. Shifts are taking place.

Manda: Yes. Even in our lifetimes. You and I both came to therapy in the 80s and we’re now 40 odd years on. And the capacity for understanding and for providing holding and return paths has evolved so much. I just started internal family systems therapy, so I’m really interested that you are referencing that. Because it feels like a whole new layer of a way of working. And maybe it’s just that it suits me particularly well where I am at this moment, but it feels so different to the kinds of therapies that were on offer 40 years ago. And richer and deeper and to have potential for healing that I haven’t encountered within these kind of modalities before. And exactly, as the moment becomes more urgent and clearly it is, and running around saying it’s urgent and we have to act I am hearing is not the answer. But nevertheless, it is more urgent. And somehow we need to find the the ways back to exactly what you’re saying, a healthy human culture, individually and collectively. And then we can move forward and explore what it feels like to live in a healthy human culture. So how do people find you and what is it that you’re offering from your corner of the world to help people find this?

Sophy: The website is healthyhumanculture.com and if you go to the learn section of that, you can find introductory sessions and the learning journey. So we have two learning journeys starting in the autumn, one starting on the 25th of September, fortnightly in the afternoon, and one starting on the 25th of October, which will be a weekly journey. And in that there are two things. One is we’re going to explore the different areas of the map that I’ve introduced in more detail, but bring other one other map as well that looks at a more systems approach. And the other is how do we apply this to our lives? So a huge part of what people get from those learning journeys is to be with other people that are interested in looking in this personal but also systemic way. That are often trying to bring more health into whatever system they’re part of, whether that is activism, schools, business, something else. So they’re often coming from different disciplines. And then to have a peer group where we can ask, what’s the alive for you? How do we explore what’s going on in the dynamics of your relationships or your groups and organisations. So we alternate between sort of conceptual teaching weeks and practice weeks, and then we’re offering more themed sessions. We’ve got a ‘how does healthy human culture help us to understand systems of power and oppression?’ coming up in October. I’m going to do a session on burnout in September as well. How do we look at burnout through this lens? What does this help us to see? The work is evolving and I want to just acknowledge the team of people that I’ve been working with to help evolve it and bring it through. The peer group who are all on the website as well, who’ve been absolutely fantastic in helping me clarify and hone my ideas.

Manda: Brilliant. And these are all online, clearly. How long do they last for? What are people signing up to?

Sophy: Seven weeks.

Manda: Seven iterations. If it’s fortnightly, then it spreads over 14 weeks, presumably.

Sophy: Seven sessions of 2.5 hours each one. Yeah.

Manda: Brilliant. And this genuinely feels transformative that this could be a key, if enough people do this and can bring it into their families, their places of work, their political systems (please!), our ways of communicating it could genuinely be transformative. So thank you. This feels like quite a good place to stop. But is there anything else that we haven’t covered that you feel that we should?

Sophy: I’d be really interested to speak with you about frames. So it’s another area that you and I have explored a bit together in our previous connections. But it’s quite a big area, so maybe that’s another conversation to have.

Manda: Yeah that feels like a whole other podcast. It is quite big and we’ve only got a few minutes left, if we’re not going to make people sit here for another hour. So let’s do this properly in the spring of next year. That would be lovely. Definitely. Thank you. In the meantime, thank you for bringing all of this together. It genuinely feels transformative. I listened to somebody the other day say the problem is not that we power everything we do with fossil fuels, the problem is that we power everything we do. I think, well, yes, that’s slightly the problem, but the problem is we don’t know why yet. We haven’t sorted out what we’re here for. And it feels to me as if really getting to grips with what is a healthy human culture, once we have got a sense of that, we can then begin the question of what are we here for? And it will emerge out of being healthy. And then everything shifts. So this feels just such an essential part of what we’re doing. Thank you so much for bringing it into the world and for coming on to the podcast and we’ll talk again.

Sophy: Thanks so much for hosting me. It’s been really lovely.

Manda: Beautiful. Thank you. And that’s it for another week. We will definitely talk to Sophy again about frames sometime, probably March ish next year, because I seem to be booked into February. How did that happen? But definitely we will come back and have another conversation. And in the meantime, enormous thanks to Sophy for bringing the healthy human culture idea and wisdom and the practice of it to the world. If you have the time and the means, whatever else you do with your life, I genuinely think that attending at least one of Sophy’s workshops will be transformative. Her capacity to bring joyful curiosity to the nature of the human condition, her generosity of spirit and her ability to see the good in people without idealising. And her deep knowledge and understanding of how we work and how we can change ourselves and our relationships with self and other, is pretty much unmatched in my experience. So I put links in the show notes to healthy human culture and to the grief tending workshops, and I strongly encourage you to follow those up. That apart, we will be back next week with another conversation.

Manda: And in the meantime, thanks to Caro C and to Allen at Airtight Studios for producing. Thanks to Caro C, for the music also at the head and foot. Thanks to Faith Tilleray for the website, for all the work that goes into making this podcast work and for the conversations that keep us moving forward. Thanks to Anne Thomas for the transcripts. And as always, a huge thanks to you for listening. And if you know of anybody else who wants to understand more about how we can heal the way that we are, alone and together, then please do send them this link. And that’s it for now. See you next week. Thank you and goodbye.

You may also like these recent podcasts

Still In the Eye of the Storm: Finding Calm and Stable Roots with Dan McTiernan of Being EarthBound

As the only predictable thing is that things are impossible to predict now, how do we find a sense of grounded stability, a sense of safety, a sense of embodied connection to the Web of Life.

Sit with the River, Breathe Sacred Smoke, Love with the World: Building a Bioregional world with Joe Brewer

How can Bioregionalism supplant the nation state as the natural unit of civilisation? Joe Brewer is living, breathing and teaching the ways we can work together with each other and the natural flows of water and life.

Solstice Meditation 2025 – Sun Stands Still – by Manda Scott

Here is a meditation for the shortest night of the year – the time when the sun stands still.

It doesn’t have to be at the moment of the solstice, it’s the connection that counts, the marking of the day. And you don’t have to limit yourself to one pass through – please feel free to explore this more deeply than one single iteration.

Thoughts from the Solstice Edge: Turning the Page on a Dying System with Manda Scott

As we head into the solstice- that moment when the sun stands still—whether you’re in the northern hemisphere where we have the longest day, or the southern, where it’s the longest night—this solstice feels like a moment of transformation.

STAY IN TOUCH

For a regular supply of ideas about humanity's next evolutionary step, insights into the thinking behind some of the podcasts, early updates on the guests we'll be having on the show - AND a free Water visualisation that will guide you through a deep immersion in water connection...sign up here.

(NB: This is a free newsletter - it's not joining up to the Membership! That's a nice, subtle pink button on the 'Join Us' page...)