#199 Making The Nettle Dress: a creative journey of attention, magic and loss with Allan Brown and Dylan Howitt

“Grasping the Nettle’ is at the heart of the film. Making a dress this way is a mad act of will and artistry but also devotional, with every nettle thread representing hours of mindful craft. Over seven years Allan is transformed by the process just as the nettles are. It’s a kind of alchemy: transforming nettles into cloth, grief into beauty, protection and renewal. A labour of love, in the truest sense of the phrase, The Nettle Dress is a modern-day fairytale and hymn to the healing power of nature and slow craft.”

This week is our one hundred and ninety ninth episode of the Accidental Gods podcast. It’s been quite a ride, and to celebrate the end of our second century, my partner, Faith, has come to join me as host, and we have two guests, textile designer Allan Brown and Dylan Howitt who is a filmmaker with over 20 years of making documentaries and features for the BBC, Netflix, Sky, Discovery – if you’ve heard of them, Dylan’s worked with them.

Allan was exploring how we could feed and clothe ourselves as we head towards a world of localism and increasing self reliance. A journey that began with a simple question – namely ‘how can we clothes ourselves?’ – led to his spending seven years of his life making a a dress from the fibres of the nettles that grew locally. He harvested them in his local wood, made the fibre, spun over fourteen thousand feet of it, hand wove it, and then made it into a truly beautiful dress for his daughter.

It was an extraordinary process of experimentation, discovery and ensoulment – a journey into possibility that would be hard to match in our current, frenetic world. And we know about this: the patience of it, the wonder, the loss, the grief, the resilience, the alchemy… the sheer magic, because Dylan made a film, ‘The Nettle Dress’ which also took 7 years and is also a process of emergence and ensoulment and magic and discovery.

The film is one of the most profoundly moving I’ve seen in a long time: it’s deep time brought into being, it offers connection and profound attention and intention as it follows Al’s profound intention and attention. It’s so, so different from what we normally see, so centering, so grounding – and when we had the chance to talk to Al and Dylan, it made sense for Faith to join me: she’s the maker in our partnership, she’s been a textile maker and designer and she thinks differently than I do in many ways. So this is a joint endeavour and all the stronger for it. People of the podcast, please welcome Allan Brown and Dylan Howitt as guests, and Faith Tilleray as co-host, exploring the making and filming of The Nettle Dress.

Dylan Howitt Bio

Dylan Howitt is a filmmaker with many years of experience telling compelling stories from all around the world, personal and political, always from the heart. Twice BAFTA-nominated he’s produced and directed for BBC, Netflix, ITV and Channel 4 amongst many others. His latest feature documentary, The Nettle Dress, follows textile artist Allan Brown on a seven-year odyssey making a dress from the fibre of locally foraged stinging nettles.

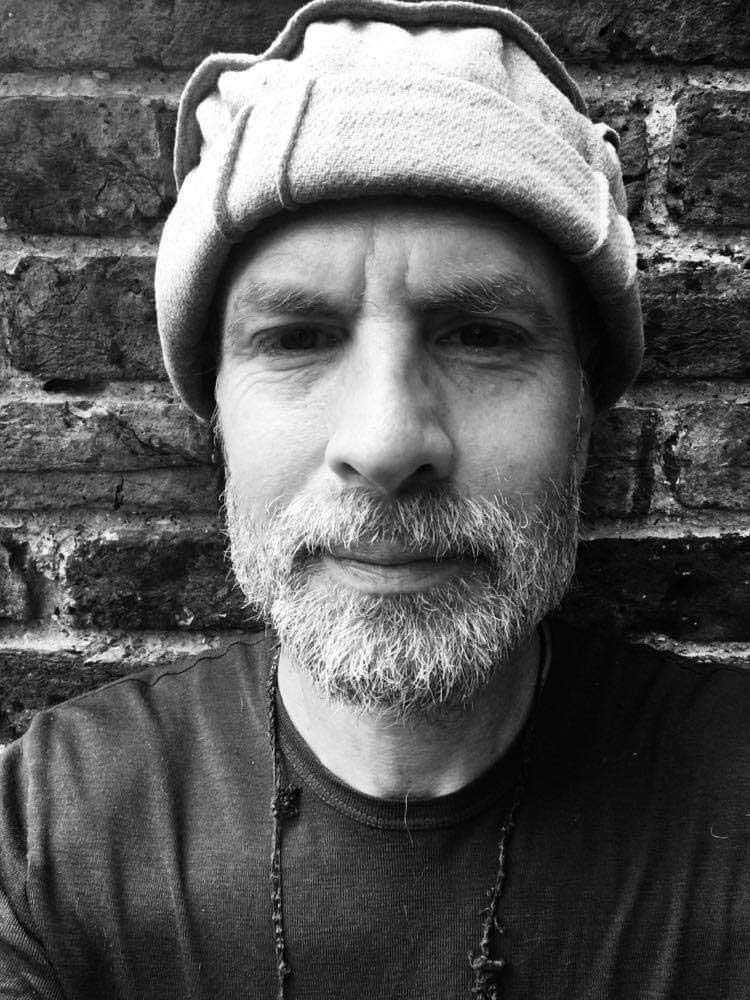

Allan Brown Bio

Allan Brown (Hedgerow Couture) is a textile artist from Brighton, East Sussex, in the UK. Working primarily with sustainable natural fibres like nettles, flax, hemp and wool, Allan takes these raw materials and transforms them into beautiful cloth with the aim of creating functional, durable clothing that draws lightly from the land, reflecting the fibres and colours of the landscape he lives and works in.

Allan Brown – textile designer

Dylan Howitt – filmaker

Episode #199

Links

All film images © Dylan Howitt

In Conversation

Manda: Hey people, welcome to Accidental Gods. To the podcast where we believe that another world is still possible and that if we all work together, there is time to create the future that we would be proud to leave to the generations that come after us. I’m Manda Scott, your host in this journey into possibility. And this week is our 199th episode. Hey, how cool is that? It has been quite a ride. And to celebrate the end of our second century, Faith, my partner has come to join me as host and we have two guests textile designer Allan Brown and Dylan Hewitt, who’s a film maker with over 20 years of making documentaries and features for the BBC and Netflix and Sky and Discovery. And basically, if you’ve heard of them, Dylan has worked with them. Alan was exploring how we could feed and clothe ourselves as we head towards a world of localism and increasing self reliance. A journey that began with a simple question; largely, how are we going to clothe ourselves? Led to spending seven years of his life making a dress out of nettles. He harvested them in his local wood. He made the fibre. He spun over 14,000ft of it. He wove it by hand. And then he made it into a truly beautiful dress for his daughter. It was an astonishing process of experimentation and discovery and ensoulment a journey into possibility that would be hard to match in our current frenetic world. And we know about this. The patience of it, the wonder, the loss and the grief. And I’m not going to spoil where they come from, but they are central to the film.

Manda: The resilience, the alchemy, the sheer magic of it. Because Dylan made a film called The Nettle Dress, which also took seven years to make and is also a process of emergence and ensoulment and magic and loss and grief and discovery. And it’s one of the most profoundly moving ensouling films I have seen in a long, long time. For me, it’s deep time brought into being. It really brings you or brought me into connection with myself; with the Land, a reconnection with the plants that are everywhere around us. It’s a meditation on attention and intention as it follows Al’s absolutely profound intention and attention. It’s so, so different from what we normally see. It’s so centring and grounding. And when we were offered the chance to talk to Al and Dylan, it made sense for Faith to come and join me. She is the maker in our partnership. She’s been a textile maker and designer and she thinks very differently than I do in many ways. That’s why the partnership works. We see the world from different angles. So it being our 199th episode, we made it a joint endeavour and I think it’s all the stronger for it. So this is our own emergent exploration of intention and attention and making and what it is to be and to make and to think and to feel in this moment of profound change. I genuinely think that watching this film will help to open doors for you. If you’re in the UK, you can see it somewhere near you. And if you can’t, you can get in contact with the distributors and help that to happen.

Manda: We have put a link in the show notes so that you can find out where it’s showing. If you’re in countries other than the UK and you have any way to bring it to your nation, I wholeheartedly recommend that you do. So here we go, people of the podcast, please welcome Allan Brown and Dylan Hewitt as our guests and Faith Tillery as our co-host, exploring the making and filming of the Nettle dress.

Manda: Allan and Dylan, welcome to the Accidental Gods podcast. It is such a delight and an honour to have you both here. Thank you. So we’re talking about The Nettle Dress film and we have, everybody listening, put in the show notes absolutely where you can go and see this, because you will want to by the time we’re finished. Allan made the dress. Dylan made the film. And we want to explore in today’s podcast the making and everything that arose from it and went into it. So Allan, welcome first. And I’d like to begin with how you got there, because I understand from the film you have Bonnie and Bonnie is a yellow Labrador, I think, or a yellow Labrador cross possibly. And walking Bonnie took you to Nettles. But I’ve had dogs for 35 years and I haven’t made a nettle dress yet in spite of there being many, many, many nettles in our walks. So how was it that you came up with the idea? Can we start with that?

Allan: Yeah, sure. Thank you for having me on, Manda. So I suppose, I mean, Dylan and I knew each other years before we started making this film. We had a shared background in the 90s environmental protests, the roads protests and that sort of thing. And I think coming off the back of that, initially it was empowering, feeling that there was something we could practically do to make a change. But I felt that it soon became disempowering as the scale of what was needing to be done was just overwhelming. And I think at the time, quite a few of the people I knew, we decided that there were allotments in Brighton that were sitting empty and idle, and it just seemed the most practical thing we could do was to actually roll up our sleeves, get our hands into the earth, and actually just start to grow some of our own food and just reclaim some sort of sense of ownership of our own direction. So yeah, I’ve been growing food on an allotment for many years. And I think that just set me down a train of thinking about how we feed ourselves in the future. The whole history of enclosures and access to land, and it just felt there was a resource right here and now that we could access and immediately get going on. And that just sort of immediacy of the action really, really spoke to me. And I think as I was thinking about food growing, the idea started to come in of like, I’ve got the food at least symbolically covered, but what about clothing? If it all fell apart, what would I actually do in order to clothe myself? And really just covering those primary bases of food and clothing, the sort of basics of staying alive, as it were.

Allan: So I was thinking about that. And years before in a permaculture course, I’d been shown how to twist nettle cordage. So it really just sprang from that. I was looking at foraging and what sort of foods were available whilst I was out walking, which just sort of grew naturally out of the growing food side of things. And so I was just trying to remember how to make nettle cordage. And I was fiddling around with nettles and I remembered how to do it. And because there was always nettles around, it was like a resource I didn’t have to carry out with me. I could just pick nettles whilst I was walking and twist cordage whilst I was on the move and as I was twisting finer and finer cordage, I started to notice that there were these incredible fine fibres in the bast, which I hadn’t really noticed before. And that really just triggered a thought of, Oh my goodness, there’s these incredible fibres right here that I could just forage incredibly easily. I wonder if clothing or thread has been made from this nettle fibre in the past? And that really just opened the Pandora’s box. I say it was idle curiosity that got wildly out of hand, really.

Manda: Right. I want to come to Dylan in a moment, but just a couple of questions to clarify before we go on. What’s the difference between cordage and thread?

Allan: Not a lot, really. I mean, cordage is just probably a bit thicker. It’s more like string. But you can twist cordage incredibly finely. And that’s really what I started doing, was just trying to get it finer and finer. And then I realised that there was a whole deeper world of these finer fibres hidden in the rough bast, which is how it usually presents itself. So yeah, it was just a refinement.

Manda: Thank you. And final question for this section; were you already a textile maker? Is the world of textiles where you come from? Because otherwise you got a lot of skills in seven years that the rest of us know absolutely nothing about. But was it your thing?

Allan: No, it wasn’t at all. I mean, I had been around textiles. My mum was a sewer. Various family members are knitters and Alex was an amazing sewer. She trained, did city and guilds and stuff. So I was around it. But I always thought it was just too big a subject to come in as a lay person, late on down the line, so I sort of let other people get on with it. So no, I had to pick up all the skills necessary to realise the cloth as I went along. I think one of the things I soon learned is that to make incredibly fine, beautiful cloth, you obviously need high levels of skill, but to make functional cloth that you can actually clothe yourself with, you don’t really need to be a master of any of the particular skills you need. Just rudimentary basics will get you a long way.

Manda: Okay guys, when you watch this film, Allan’s idea of rudimentary basics and mine don’t quite match, because your level of patience, never mind anything else, is astonishing. But we will come back to that. I would like to have a chat with Dylan now. Because the nettle dress itself, the making of it is an astonishing seven year process. And the film is one of the most beautiful that I have ever seen. It’s moving, it’s meditative. It’s got that sense of we could do this. It feels to me with one of my obsessions of how do we create the stories that will take us forward to a different way of being, that this film is one of those. It opens a doorway to different possibilities and different ways of being. And we wouldn’t know about the nettle dress if you hadn’t made the film. And Allan’s just said, You guys have a history. You went back to road protests and things. So I have a starting question of did you become a film maker to change the world? And welcome, also.

Dylan: Thanks, Manda, and thanks so much for saying that about the film. That’s lovely. Did I become? I don’t think I did. My first love was drawing and painting and from that into photography and then into film. I made funny little animations, Super eight animations. And then, yes, at art school I did start to sort of connect with possibly doing documentary films and sort of engaging a lot more with the world. And that film could be a powerful force for change. So when I was involved in the environmental roads protest movement of the 90s, I ran a group called Conscious Cinema. And we’d show a lot of films about environmental issues in all sorts of places, like, you know, sometimes in the woods with a sheet hung up amongst the trees and projecting the film onto it, like that. But one of the interesting things I think about that time, was we used to make films and then we’d cut a little short film together we’d show it. We’d do these sort of screenings, often to the very people who were on the action. And so in a way, it was the very definition of preaching to the converted, because we weren’t growing the movement at all. But what I did learn was the great value of cinema actually. Of telling a story within a group, reflecting it back in a very tight loop. This is what you are. This is what you’ve done and it’s amazing. That that kind of feeling.

Dylan: And I sort of think the roots of that are here in The Nettle Dress. Because a lot of craftspeople and artists have come to see the film and they feel seen. They somehow feel like, yes, you’ve shown the value of what it is we do. You know, that even knitting a scarf is a profound act of love, and that somehow they feel seen by that. And so it’s that notion that also I’ve learned from doing a lot of therapy, which is of the value of somebody reflecting back to you who you are and what it is you do. So at that time, it wasn’t really changing the world, even though I was trying to, but it really wasn’t growing. It was an attempt at propaganda and that was a mistake because nobody wants to be preached to. So this is a different kind of story. We were tempted with this story to load it with facts and figures about unsustainable fashion and this and that. We did speak about a lot of those things between us and had it on camera, but in the end removed all of that. Because it’s implicit. And to use the analogy of what the film is about, it’s in the fibre of the film. It doesn’t need to be said actually, it’s acted, it’s a lived experience.

Manda: So yes, because there is a tiny moment where Allan says that he discovered that I think it was 200 billion tons of fashion clothes made every year, most of which ends up in landfill. Which just that one statement splintered my brain open. I had no idea. And then it takes seven years to make this beautiful dress, which would then become an heirloom. That sense of connectivity. You’re right, you didn’t need the extra because we are capable of filling in the gaps. I want to look a little bit then with you, because you are a storyteller. Our ancestors sat around fires doing exactly what you just talked about, telling each other stories of what the group had done. Let me reflect to you the story of how you, I don’t know, hunted the wild boar and were amazing. And now we’ve got enough food to eat for the next couple of weeks and this is extraordinary. That was what we did. It’s our evolution. And I learned recently that the cave paintings in France, the culture that created those spans 25,000 years.

Dylan: Wow.

Manda: That’s twice as long as the the history of agriculture and it was a stable culture and one assumes they were telling each other stories around the fire of what they’d done. So what you were doing with your early projections on a sheet in a wood, which I think sounds glorious, is sitting around a fire telling people stories of what they’d done. Which in many ways is how we find who we are. And so I’m wondering now with the film, because you aren’t just telling Allan and the family what they’ve done, you’re expanding it to wider people. What was your vision at the start? Or did you have a vision at the start or was it just this sounds like an interesting project, I would like to record what you’re doing as you’re going along?

Dylan: To begin with, it was the latter. It was you know, it was just, wow, this is interesting. It started with a sense of wonder. That was probably my starting point. In a way similar to what Allan just said about his inspiration. Because when we first went out to film and Allan asked me to make a short ‘how to’ video that he could share what his experiments were with nettles. And we went out and I would probably put the kind of inspiration down to two moments. One was when he opened up the nettle to reveal the fibre and it just felt like, Oh my God, wow, look at this sort of hidden treasure in this plant that I pass by every day. And I had no idea. And he sort of opens it up and there it is, this golden fibre. And the second was watching him spin. Because, you know, I’m so ignorant and so naive that I had never really thought what thread is. You know, I’d never considered that it’s just this fibrous material with added twist, is all it is. It’s just adding twist to give it its strength. But to see Allan spinning by hand, it just felt like something wondrous and so inspiring. And it made me think of all the religions that have thread as a sacred object. There’s so many beautiful parallels between storytelling and textile making. In years of making films, I’ve always thought when I’m editing, of the threads of a story. But, you know, there’s all the phrases that we have embedded in our language about weaving spells and text and textiles and life’s great tapestry and all of these things. So that was an inspiration as well.

Manda: I had never made the link between text and textiles ever, and I live with a textile maker, Faith, amongst many other things. I’d never seen that before. Is it actually the same root or is that one of these coincidences?

Dylan: No, I think it comes from the same root. And I think, you know, it’s something that actually Allan, another thing that he’s mentioned that I think is lovely, there’s so many we could go on and on about. But people who work in textiles, they’re good at chat, they’re good at talking, often. Because it’s something that you, you know, your hands are busy knitting or sewing or weaving, but then you’re free to discuss. And so when you go to a weaving or a kind of spinning circle or when you get together with a few, there’s always really great conversations.

Manda: Yes, all the knit and natter groups around the country and all of that kind of thing. Yes.

Dylan: Yeah, it’s just so conducive to that, you know? But you know, there’s so many sort of beautiful parallels with filmmaking as well. I mean, even when I was looking at the timeline of my edit, it looks like a weaving pattern. You know, you’ve got the layers of the video and the layers of the audio and they’re all kind of crossing over each other. And if we were doing a sort of conceptual art piece, we might weave the timeline of the film. But yes, that’s not the thing we’re doing.

Manda: Yes. I so want to see the kind of producer’s cut, the the six hour version as opposed to the just over one hour version. That would be rather good. At what point did it stop being a how to video on nettles and become what it is, the much longer and very beautiful meditation on a whole process?

Dylan: You know, the great blessing in disguise that we had with this film was that we tried and failed many times to get funding and we never did get funding. And lots of funders said, Oh, that’s very nice, but it’s very niche and nobody’s really going to be interested in that.

Manda: And how wrong were they?

Dylan: Yeah, and but it was a really, really great thing because in the end, you know, we could make the film we wanted to make. And this is a really important thing, we could take as long as we needed to take. I’ve worked in a more industrial model of film making, working in television or working for clients and so on. And obviously the way that the economy works is you’re paid by the day, so therefore the pressure is always to make something as quickly as possible. And that means in practice that you generally have the story in mind before you go and start making it. And so, I might have a brief to go and see this textile guy and maybe you’ve got a day to go and talk to him about nettles. This was the polar opposite of that. And it was wonderful, because it was a conversation with no particular output or you know, there was no one breathing down my neck. So it could be open ended. And so I like to think of the film on another level, as a sort of slow motion conversation between the two of us, that took place over years.

Dylan: And that’s how it became what it became. Because as we were talking, you know, sometimes really interesting philosophical ideas will come up. Or little keys would appear that would just open up other avenues in terms of the narrative. Let me just give you one. This notion of stories captured in thread, right? You know that Alan talks about that he has this lovely phrase that this was like prehistoric photography. Yeah. So that somehow experience is captured in thread as you’re, as you’re spinning it and as you’re weaving it. And I thought, wow, that’s amazing. And it really, really resonates, because that’s kind of what I’m trying to do with filmmaking and trying to capture the magic of moments and then somehow join them together into threads and story threads, you know? So along the way it just got deeper and deeper because we would keep cycling around the themes. Whether it’s themes around loss or whether it’s about creativity or, you know, around the sort of environmental or about connection to plants or all sorts. There are so many things, but all of those came up and we would spin around them, we’d circle around them and keep coming back to them and kind of go a bit deeper each time.

Manda: It’s like a fractal, isn’t it?

Dylan: Yeah. And that’s how the film came to be what it is now. And it’s very instinctive really. I think for both of us it was like a good conversation. I know you know that Manda, because you have them professionally on this podcast. But it’s more like improvisation; they go to unexpected places if you’re alive to that. If you have an idea already, then you’re just trying to get that and then that’s quite boring.

Manda: Yes, exactly why don’t ever script anything, because it would be horrendous. Thank you. And the thing is, what you came up with at the end, what you’re many, many, many, many hours of filming, is so alive and yet is so focussed on attention and intention. So I’d like to move back to Allan now for a little bit. I think Faith is probably, if I know anything about her at all, going to want to ask you about stories in thread. But I would like to ask a little bit. And I need to get my thoughts organised here. So my own spiritual practice is shamanic. I have no idea what your spiritual practice is, but I’m 99% certain that you do have one because of the way that you talk and the way that you relate to everything. And I will leave Faith to talk about stories in thread, if that’s what she wants to do. Okay. She’s not nodding. I will talk about stories in thread then. Grand. But I want to talk about the feelings in the thread, because there are several times in the film; your father dies, I imagine, during the making of the film and then your wife dies. But even before that comes up, you’re gathering nettles while walking the dog.

Manda: And nettles are, for me, fierce warrior characters. They’re lovely and sometimes they’re very feminine and very spring like and I drink nettle tea in the spring and it’s very alive and it has that sense of maiden dancing ness. But there’s also the fierceness of nettle, because they sting. And you have an extraordinary part where you’re bare handed, got these huge nettles that are like trees, taller than me, and you’re stripping it and creating the fibre. And so it seemed to me that all the way through this film you’re gathering the nettles and then particularly the spinning, because that took five years, if I understood correctly, with a drop spindle. You’re not using a spinning wheel. It’s all totally very connected in the way that drop spindle spinning is and wheel spinning slightly less so, it feels to me anyway. And that the thread is then imbued with the feeling. And I wonder if that’s true for you? Second, how that changed and then to what extent do you feel that becomes part of the fabric? Over to you too? Just a general meditation on feelings in the making.

Allan: Right? Yeah, a bit to dig in there. My sort of gateway into it was nettles, but as I was experimenting and trying to find out how to actually get to the fibre in an efficient manner, I was searching around on the internet trying to find if there were any how to’s on how to actually do this process. And also just to find examples of nettle cloth. And I think if I’d been shown nettle cloth right at the outset, I would have gone, oh, that’s what it feels like. Cool. It’s possible. But I couldn’t find that. I found lots of rumours and references to nettle cloth, but nothing that I could actually get my hands on. So that kind of forced me into going, Well, if I want to feel nettle cloth, I’m going to have to make it myself. The one area where I could get information on, was the Nepalese. They’ve got a long standing tradition of working with their nettle, a Himalayan nettle. It’s a bit different to our nettle, called Aloe by the Nepalese, and they process that in a very different way. I did try their method, basically boiling it in wood ash and packing it with clay to stop it clumping up, but they end up with a very long fibre.

Allan: What I discovered with the nettle, even though it’s a bast fibre so very related to flax and hemp of which we know a lot more. When I failed at the Nepalese method of extracting the fibre, I looked towards the literature of hemp and flax growing of which we have a much longer tradition here in Europe and there’s much more written about it. And so I set about really emulating those steps and seeing how much of it could be applied directly to Nettle. I started growing flax on my allotment and getting getting into that process. Went on a course with Simon and Anne from Flax Land, who basically single handedly brought about the flax revival in the UK. But I realised that nettle, like hemp and flax, are these incredible plants. I mean, there’s a Danish textile researcher called Margaret Harold, who called Nettle a culture plant. Just because it feeds us, you get fibre from it and it’s a medicine. And really that applies to both hemp and flax. They’re just these incredible plants that feed, heal and clothe us. So that that was an interesting discovery. But I’ve already nattered on and lost track of the other parts.

Manda: But I have an ancillary question anyway. Because years ago when I did a permaculture course back in the early 90s, I was on the course with a gentleman who was then in his 50s and he said that after the war his mother had made him a nettle shirt. And I thought, Oh my gosh, like hair shirt. Was that nice? And he said, Oh God, yes, it was gorgeous. It was the best shirt I ever had. And he was 10 or 12 at the time. And and I discovered after that he was Serbian. So my assumption was that in Eastern Europe there was a long tradition of making shirts. And now I’m thinking, my goodness, did his mother spend the entire Second World War gathering nettles and spinning them to make this shirt? He would be quite small, so it probably wasn’t as long. But did you not find anything in terms of European nettle production?

Allan: Early on I met a wonderful woman called Gillian Edom, who wrote this book called From Sting to Spin, which was the history of nettle fibre. And she was very articulate and very thorough in her research. And again, it’s interesting, she doesn’t know where the thought to do this huge labour came from. It just felt like the nettles grabbed her by the scruff of the neck and told her, This is what you’re going to do. So that was useful in seeing that Oh, yes, there are definite examples. And I think really the heyday of Nettle was probably way back, sort of Neolithic Bronze Age time. I mean, it’s difficult to tell because, you know, woven cloth rarely survives. But there are lots of examples and it’s really interesting to see how finely people were spinning nettle at that time. It wasn’t a rough cloth at all, even though the way it was processed was different to the way I did it. Because this was all being done pre metal tools and carders and all that sort of kit. So it’s interesting that Eastern European connection. I think Gillian found that and I’ve certainly detected hints that the tradition lasted a lot longer in Eastern Europe and also up into Russia.

Allan: I think the history of where Nettle was used is probably very related to the spread of flax and hemp as that colonised or moved into different parts of Europe. Also I think where nettle seems to have been used most predominantly both over in the Americas and in Eastern Europe, seems to have been places where there was heavy snowfall over winter. Because in our milder climates down here in the south, once once autumn comes in, the nettle fibre that’s left standing in nettle groves degrades really quickly. The wet weather just rots it down. So come spring, nettles are basically all gone. But in places where there was deep snow the nettle would be preserved and just naturally retted in the snow. So as the snow started to melt in early spring, the nettles would be collected then and the fibre can just be stripped off and it’s already in a perfect condition for textile uses. And again, the etymology is interesting that, you know, it’s not a coincidence that nets and nettles share the same root. And in fact in a lot of European languages, nettle, needles, sewing all share a similar root.

Allan: So it gives the sense that this was an ancient practice using nettles. And we know that the use of flax goes back at least 30,000 years, but obviously it goes back a lot further. And I think nettles do require more work than flax and hemp to process. So I think as other fibres naturally started to appear in regions or were imported and grown purposefully, that they probably soon replaced Nettle. For example, in Gillian’s book she talks in Scotland, there’s a lot of reference to nettle cloth which carried on right up until the 19th, even 20th century. But it was really a term that was then being applied to all sorts of different fabrics and fibres that were being imported from the east. Rami being one of them, even cotton muslin was called nettle cloth. There was just a sort of memory of nettle, even though the actual thing being referred to was no longer nettle. The phrase popped in my head quite early on that nettle is the fibre of the landless and you know, it’s that one very easy forageable fibre source.

Manda: Right, yes.

Allan: I imagine that nettle was used, when other fibres became introduced, Nettle was used when crops failed or you needed to bulk out flax or hemp growing.

Manda: There is always going to be nettle somewhere isn’t it?

Allan: Yeah, exactly. So yeah, I mean it’s a very interesting history and we could speak for hours just on that alone. But that’s my sort of understanding. I mean, it was interesting that the little film Dylan and I did, the How to video, which was called Nettle for Textiles, which kick started this whole thing off, which we just put out for free. We put it up on YouTube and it was ripped by someone in Russia and they re-did the subtitles and dubbed it into Russian. Cut Dylan and I’s name off.

Manda: Ripped off by a couple of Russians! Grand.

Allan: But that has had so many views in Russia, like tens of thousands. And again, it just seems to speak to a more recent memory of Nettles being still in the culture. So, yeah, that’s been interesting.

Manda: Brilliant. You’re right, there are so many avenues we could go down there. I’m thinking Faith will go down some of them. I want to come back to my earlier question of feeling in the fibre and stories in the fibre. You said at one point if you were going into battle you would wear a nettle shirt because it would repel everything. And I remembered the stories of the ghost shirt warriors amongst the Lakota. I think it was Black Elk’s dream, somebody dreamt that they would wear a particular shirt and it would repel the bullets of the white invaders, which clearly didn’t quite work. But I’m thinking two things. First of all, it probably would have worked better if the people coming at you had believed the same things. And then I also saw something come past, I think, on YouTube a couple of weeks ago where someone had practised gluing, using, I think, boiled cows feet glue. They glued 15 layers of linen together to make armour, and they made the mistake the first time of just making a big sheet, thinking they’d cut it up and put it together and they couldn’t cut it. They ended up with the same kind of power tools that you cut metal with, failing to cut this linen armour that they’d made. And the next lot they made, they shaped it all first and then glued it all together. And so if you did that with nettle, I guess you would get quite impressive armour. How does it feel? I’m really wanting to get to the depths of that sense of does the mix of however Nettle feels to you, as a plant spirit and your own feelings as you were over five years, hundreds and hundreds and hours of spinning this thread; does the fabric at the end of it seem to you to carry the essence of that?

Allan: Yeah definitely. I mean, I got that sense really strongly in the spinning. That the sounds that were around me as I was spinning, what I was thinking while I was spinning, the memories and thoughts of both the location externally and internally must be going into the thread. Even if it’s just a symbolic wrapping in of those things into the thread. Definitely I got the sense that for most of our history when we were making clothing for each other and for our small tribe, that when you wore a piece of clothing, it would have had the thoughts and hands and sweat of those people that loved you all accumulated into the garment itself. So it’s like you’re wearing something that’s filled with intentions. Filled with the dreams and aspirations and struggles of those around you. So the cloth is like a repository. When the cloth. When the nettle cloth first came off the loom, you could see it’s banded. There’s different batches of nettles and they’re all slightly different colours. And at that point, you know, I might not remember that was that day and that was that day. But there were definite differences in the threads. And also if other people had been contributing to that, there would be subtle differences in the spinning. Having watched lots of people Spin Nettle, it’s incredible that it’s almost like a fingerprint. You could probably pick out who spun what.

Allan: The dreams and aspirations that go into making that cloth just enriches it, imbues it with a sort of magic which is so different from the industrial model where if those threads do carry stories, they’re probably aggressive stories of exploitation and loss and labour. As you can see, I’m quite romantic in the way I think about these things. But that’s how it appeared to me. Once the cloth was woven, off the loom, scoured, been worn and touched and exposed to sunlight, those differences of the batches has sort of disappeared. And it’s become a unified new story, rather than being able to pick out the individual stories within it. I mean weaving is magical like that, it just takes the individual threads and then creates a new thing. Those stories are in it, but it gives it a fresh start, as it were. So yeah, those themes definitely ran through it.

Allan: Earlier on you were talking about the spindle. As it was, I did use he spinning wheel as well. But what I loved about the drop spindle was that it just fitted into using all these small pockets of time in a productive way. So when I would take Bonnie out to go and pick Nettles, I’d have a bundle of nettles in my pocket that needed hand-rolling so I could do that whilst I was walking. I could spin whilst I carried the bundle of nettles back home. And the spinning on the drop spindle it all took place in moments which would otherwise be unused: waiting for the kettle to boil, waiting at a bus stop, watching tv, listening to a podcast. That sense of producing in all these down moments. When it got on the spinning wheel, that was more dedicated and it felt like I was just trying to move things on. But the way the spinning on drop spindle just seamlessly fitted into all the other jobs that needed doing in a day. It never felt like drudgery at any point. It always felt like there was, however small, a sense of movement happening, which is very different when you’re being forced to do it for low wages or for someone else; immediately it would become drudgery. But when you’re producing it more out of artistic creativity or love, it doesn’t have that that feeling about it at all.

Manda: Brilliant. Thank you. So, Dylan, coming back to you, and then I’ll let Faith talk some more to Allan. I’m still really curious with this film; we have a culture just now where there is the race to the bottom of the brain stem. Let’s give everybody a little dopamine hits as much as we can and disconnect us all from the web of life. And your film seems to do the opposite of that. For me, it’s a serotonin and oxytocin film. And in shamanic terms, it’s a very spirit based film. It’s got a lot of fire in it. There’s the scene at the end where Allan’s daughter is wearing the dress and she’s got the skull over the fire and you’re honouring and offering to the spirit of the woods. And I’m wondering, did you dream with nettle? Did you dream into the film? What was the spirit energy as you were making the film? Does that even make sense as a question?

Dylan: Yeah, I think it does. My first thought in answering it would be that the making of it was a conversation. You know, I like that metaphor more than anything, and it was a conversation between the two of us that I’d already mentioned, that took place over the years. But it was also a conversation between Allan and the Nettle itself and between me and the material and between me and the place. And so, yes, I would go on my own as well to Limekiln Wood, which is where most of the nettles came from and just sat there and then just tried to catch it in so many different seasons and so many different lights and weathers and try to make a study of the place and also the nettle itself. So you can see that as one of the threads running through this too, through the film. It’s a study this plant, this humble plant or mighty plant, how ever you want to see it. So for me, one of the discoveries making it was what is it to go again and again to a thing and just keep looking and keep going and keep asking and and keep studying. And the depth that it gives you back? And something Allan says in the film, as much as he’s working the nettles, the nettles are working him. You know, it’s that notion in creativity that if you’re open to it, as much as you’re working the material, you’re talking but you’re also listening and it’s a journey, and it’s one that you don’t know what the destination is. But it’s opening up all the time possibilities and it’s going deeper. And that was the sense I had in terms of kind of on a spirit level, I guess, with both the plant, with the place, that particular wood, which as Al says in the film, it’s a humble wood which you would walk past, you wouldn’t even notice.

Manda: And it’s surrounded by industrial farmland. I hadn’t realised until you get kind of, I think, a drone shot towards the end of, my goodness, there’s this tractor, rows of the worst of what we’re doing to the land. And this little wood in the heart of it that’s still alive. Because all the shots going through the wood, you get the sense that this wood is huge and actually it’s it’s little.

Dylan: It’s quite small. If you went there, you’d be shocked. You can walk through it in five minutes, you know. But again, it’s that sense of the wonders, the simple wonders that are right here with us now. And everyone listening to this I’m sure has a park or a copse or something, a wood, that’s near them where all of these things are there. So it’s the simple wonders, I think. And actually, one thing when we were making it that was an inspiration was actually something that Mark Rylance said. He wrote a beautiful article and he was talking about artists having a responsibility to tell love stories about nature. We need to tell the stories that connect us back to these these places that actually, I think during lockdown, during Covid, I think a lot of people did start to discover. And find those places again or discover just how beautiful their local park can be if you just stop and notice. And so that was another revelation, I suppose, was the slowness.

Dylan: You know, lots of people have asked, how could you be so patient to make the dress or to make this film over so many years? But to me, that was the most wonderful thing about it. Maybe it’s something about my own character being maybe more on the introvert end of the scale. I find I’m one of those people who, when I have a conversation, you know, it’s bouncing around in my mind for hours after and I’m still having the conversation in a way. I’m still having revelations. And so it really, really suited me to make something slowly. You know, to sort of to sit and talk with Al or to go and film and then to contemplate and look at what I’ve done and let it sort of go through me and just resonate really naturally and instinctively, and then go again and then go again. Just like that. Just let it be a deeper relationship with the material.

Manda: And with the plants also, obviously with the nettles.

Dylan: Yeah. And it strikes me that the sort of the quality of storytelling and communication we have in so much of our media, that space for contemplation isn’t allowed because of the way we make it. And I mentioned it earlier about the pressure to make things and just relentlessly churn out stories. So it’s partly about about that. That storytelling and filmmaking is almost an extractive industry, right? And I’ve been guilty of it myself when I’ve worked for charities and such where I’ve sort of flown in to a place and I’ve just taken the story and off I go and I’ve used it for the purposes of whatever the institution is or whatever, right? I have this feeling that how we tell the stories is as important as the content. That it’s done in a respectful way and a loving way, and that it’s responsible. This notion of the egotistical artist, you know, where the ends always justify the means is one that is not serving us, you know.

Manda: And so taking this a little wider, this is a question I have been asking myself a lot. If I were to write a film script of a Thrutopian story, which is how do we get from where we are to where we could be if we became the best of ourselves? Would it be possible, logistically possible, to make that into any kind of television, given the inherent, as you said, extractive nature, but also just the carbon load of making something. Because it’s not all about the carbon and I don’t want to suggest it is, but is there a way that we can take this medium, which is our storytelling, It’s the storytelling of our culture. We have the capacity to then tell stories that reach millions instead of ten people around a fire, which could be amazing. But it has seemed to me that if I make a story that’s about systemic change and paradigm shift, and I make it in the way of the old system and the old paradigm, the energy has already gone before I start. I’m again thinking, is this even making sense as a question? But you’re in this industry and it seems to me that you’ve made a Thrutopian film. This is a film of deep time, which I think is what you were talking about. It’s a film of what it is to pay attention and intention and slow down and really connect. And I’m guessing that it seems to me as if you were a producer, director, cinematographer, all of it. Basically it’s you and a camera and then you and an editing suite. If it’s possible to do this in a way that is actually regenerative, then you have done it. First, is that true? And second, is it scalable?

Dylan: That’s a really big question. I think I’m living that question. Trying to do that. I think in terms of a regenerative practice, is something I’ve been thinking about a lot. I think that the making of this film and as much the showing of it, because I think the work is still continuing by the way, I don’t think it finished when when we finished the film.

Manda: Please say more about that.

Dylan: It’s as much about the showing as I said earlier, I really believe in the power of cinema and sitting together and watching a story. Television I find very unsatisfying. So cinema is really important and the energy that is in the room and the discussions that happen afterwards and the connections that are made between people. And the synthesis of ideas that happens when you talk about it with your friends afterwards, which doesn’t happen when you’re sitting at home and watching telly. So all of those things have been really good. But yeah, in terms of the regenerative practice, I mean, I think it’s been really regenerative for both of us in terms of the wonderful feedback we’ve had. So that’s been really great. But I have to say, just on a horribly practical level, it isn’t in a financial sense. In that sense, it’s a fairy tale. Because we can’t all go out and make nettle dresses spending years of our time doing that and we can’t all go and make films for no money, because we have to make a living.

Manda: Yes when we’re in predatory capitalism, we have to make a living. At the point where we don’t have to make a living anymore, then that’s exactly what you do.

Dylan: Exactly right.

Manda: But we’re not there yet.

Dylan: So that’s the part that I haven’t squared yet. And I’m trying to figure it out. So watch this space.

think we’re heading to, we’re going to have to be making the nettle dresses. This is where Allan started. We’re going to need to be feeding ourselves and clothing ourselves without having young women in China chained to a machine to do it for us, because that just won’t be a thing.

Dylan: There’s an interesting thing as well about how you bring people to a film like this. Because we’re literally showing in cinemas alongside Barbie, which had a $150 million marketing budget. Or we’re showing alongside Avatar two, a couple of months ago, you know. And these are big, noisy films and they demand attention. And I think the big thing with the nettle dress, that I’m very proud of, actually, is it doesn’t demand anything at all. It just invites it. It just says, you know, come along with us if you want to. Just watch Bonnie and enjoy Bonnie.

Manda: Yes. Or you want to explore Allan’s beard. The story of Allan’s beard. It’s amazing.

Dylan: Yeah. But because of that, it’s been a struggle getting funding and even getting distribution. Although now we have a distributor, which is fantastic, right? There’s something, you know culturally about how do you sell it? Which is a horrible way to put it. I hate saying it like that, but it’s how do you bring people to it when it’s quite quiet, you know? It’s that really.

Manda: And how can people? Because over half of our listenership is not in the UK. Have you got a distributor for other nations?

Dylan: Not yet.

Manda: Okay. So anybody listening?

Dylan: Again, there’s a lot of interest in the US. There’s a lot of interest in Canada and in certain countries in Europe.

Manda: And probably Russia When they find it. They’ll rip it off and put Russian over the top.

Dylan: I hope not!

Manda: Yeah. Okay. All right. But anybody listening if you have ears for a distributor, let us know. I have so gone over the time that was allotted to me, so I’m going to hand over to Faith now and then come back to say goodbye to you guys at theend.

Faith: Hello, everyone. Hello, Allan and Dylan. It’s wonderful to be here and be able to talk to you. Usually I hide behind the scenes, but my total resonance with your project and I was so inspired by it, has drawn me out into the podcasting chair. So it’s really great to be here. I’ve made some notes kind of going through, watching the film a couple of times and there’s so much I could ask you. But I don’t want to kind of tread on the same ground that Manda’s already covered. I’m thinking that she probably didn’t talk too much about your relationship as a maker with your materials. Because it seems to me that this was such a two way process, the making of the nettle dress. You said at one point that metal was demanding something of you, a different way of being, kind of in order to unlock its secrets. And then you talked about everything that you were thinking and feeling was being recorded in the thread. So it seemed to me that this two way relationship with the materials was a really important aspect of the making. And I wondered if you could say any more about that; the feeling of the material in your hands and your relationship with it.

Allan: Yeah, sure. Thanks for the question, Faith. Yeah. I mean, I think because at the outset I didn’t have a handy how to, to actually know how to go about extracting the fibre in a way that made it suitable for spinning and ultimately cloth, is that I just did a lot of experimentation. I mean to fast forward a bit, once I was starting to be able to extract a good fibre, knowing how to spin it is a really immediate two way conversation. Because the basic principle is that you’re just trying to add twist to it, to get it to hold together. But you only improve or adjust your spinning because you’re directly relating that the fibre is sort of telling you how it wants to be spun. So whilst there aren’t vast differences between spinning wool or spinning another fibre, the principle’s the same, Nettle showed me how it wanted to be spun. Because if it was coming apart, it tells you it needs to be spun tighter. Licking the fibres, the yarn, as I was spinning to sort of try and glue down the hairiness of the fibres, which becomes important when you’re actually getting to weave it. When you’re changing sheds with a hairy fibre, they tend to snarl up and that sort of gums up the ease of the spinning. So there wasn’t a rule book that I could refer to. So yeah, the nettle had to teach me itself and in a way that was really freeing. I tend to, when I learn a new thing, I’m immediately aware of how much I don’t know and I want to fill those gaps with someone who’s been there before and given me the fruits of their labour.

Allan: But I just didn’t have that with Nettle. So all I could do was just keep experimenting and practising with that fibre and it did start to feel like a conversation that was going on. And then just noticing that nettles grown in full sun had a harder woody core and maybe later in the growing season it was a bit harder on my fingers to actually open the nettles up. So naturally I just started to look for nettles that were grown more in shaded areas, because they they were growing tall up to the sunlight, but they were quite soft. They looked like a gust of wind would blow them over, but the core was much softer. They were easier to get into. And, you know, I think there’s still a lot more nuance that I’ve got to learn from the nettle. These feedback loops improved the results. So it was sort of spiritually like a conversation, but all of this was really rooted in just practical, pragmatic, technical, how to make it easier. Which type of nettles were easier to work with, what was the fibre like? And I kept notes. When I went out to harvest nettles, I would record the day I harvested them on, where they were grown. And then when I spun them, I would make notes of how much fibre I managed to get per plant. Work out averages and that sort of thing. Emotionally and rationally, just building these feedback loops to improve the process.

Faith: So there’s something here that’s very different for me. When you look at the world that we’re living in, people are making things all the time to the point where we’re making too much stuff. And I suppose a lot of the art world and things that are sell for loads of money, you know, they might be made in a laboratory or from spun filaments of plastic or something, with which the person making has no two way relationship that you’re talking about.I found that really moving and the fact that it was a transformational relationship. So this nettle dress, in a way, it wasn’t just made of nettle, it was made of your relationship over that period of time with the nettle. So I’m wondering how that works, Dylan, when you’re making a video. Because I know we’ve got lots of artists and makers who listen to the podcast who are inevitably drawn into filming their work or filming their process, and that has almost become as much of a time consuming thing as actually the making of the thing. But sometimes I feel if I’ve made something and then videoing it can also, just by the time spent looking, you haven’t got a physical material in your hands like Allan had, but there’s still something in the making which has the same quality. I don’t know if that’s making sense as a question, but is it something about time spent or the quality of the looking or the seeing? Or is it recording moments of time in which you’re present? Or how does it compare making a video to making something that you can feel in your hands?

Dylan: That’s a really interesting question. Not one I’ve had before. I mean, I did like to see the two crafts that we had running alongside each other as parallel crafts and very similar in lots of ways. But I know it’s not the same. I mean, I know that for Allan it was the feel. And that was actually the question right at the beginning. What does a nettle cloth feel like? Is it possible to make it and what would it feel like? I know it’s not the same for video at all. That’s different. But in so many other ways it was similar in terms of the process, you know, the going out and gathering the material. And then the sifting, the wheat and the chaff, sifting the best bits and then joining them together into story threads and then weaving the threads together to make the final piece. And then the finishing, which so much of making clothes is hiding the seams, you know, making something seamless. So all of those things ran alongside. And the thing that came to mind and I don’t know whether this answers your question, but when you were talking was, it strikes me that when we see a work of art, you know, we’re only seeing the final incarnation. You know, we’re seeing the final bit. And I know there’s a phrase that’s sometimes said about film. A film is never finished, it’s abandoned. You know, it’s just the final bit when the maker just stepped away.

Dylan: Because of that, when we consume, we’re just seeing the final thing, we’re not seeing the story. We’re not seeing the making. We’re not seeing the blood, sweat and tears and the love and the attention and the intention that went into that thing. I suppose what I thought of when you were speaking, was just part of what the film was about, was to show that, you know, if you saw the dress in the museum or something, you would think, Oh wow, made of Nettles. Looks and feels nice. Lovely. But it’s very different if you see Allan over years and hear his reflections over all that time and sort of see what’s threaded into the making, in terms of the story of it. So I don’t know if that answers your question. Maybe it’s because we both went to art school and I’m very interested in process and I’m very interested in creativity and what does it actually mean to make, you know, in terms of just moment to moment, what is it to be creative? And it’s to me, it’s about paying attention. When I’m watching Al, it’s just lots and lots and lots of moments of attention, you know, lots. And they’re all adding together. And lots of little tiny decisions and they’re all becoming, seeing this thing kind of coming into being from all of that attention.

Dylan: And as I was thinking about attention, I was reading around it and stuff. And I found a lovely definition of love, which is just love is attention. Love is paying attention. You know that we pay attention to the things and the people we love and we love them by paying attention to them. And so extrapolating from that, you can see what Al’s done over all these years as a profound act of love and devotion, because it’s hundreds and hundreds of hours of attention. And connection as well. That’s the other thing I think maybe that has brought people to the film. Lots of people say, I felt so connected. It’s meditative, because I think craft teaches us that, and creativity. Which is that when you try and draw something, you have to connect, even if it’s just for that moment, you’re trying to catch it. And you’re trying to draw a little mark, and then you look again and not quite right. Another little mark. Each time you’re doing that, you’re connecting. It’s a little bit of not being on your phone, not being distracted. Because we’re all, you know, I know for myself that my attention is terrible. So this is an antidote to that, I think. And I think that’s maybe why a lot of people have responded to the film.

Faith: I certainly responded to it in that way. And I’m sure a lot of our listeners will. Something that Al said just linked in to what you were saying. There was a moment where all the wefts all set up on the loom and you were starting to weave and you said that you stopped worrying about where the next thread was going, because it was already laid out where the thread had to go. The weft is already there, the lines of it. You just had to follow the thread and do the next thing. And then when you zoom out, there it is. The rich tapestry of your life has been laid down. Has literally become material. And I really loved that idea of making, whether it’s a cloth or video, as a kind of making your life energy material becoming a thing. So the life force of the nettle, your relationship with each other, your relationship with both of your ways of working, the love and attention that you were just talking about. They’ve been made material in a dress and in a film, and it’s so precious, you know. I know Al said, you said at one point that the dress became a kind of ritual object, a precious thing, just because of all this energy poured into it.

Faith: So I guess that’s left me thinking that one of the things that inspired us when we started the Thrutopia project about telling stories to move us forward into a new way of being, was Ben Okri. A question he asked, What should we make, if this is the end of the human era, what should we make? And I know a lot of artists and makers get crippled by this question. What’s the point of making anything in a world which is drowning in stuff? So I just wondered, now having completed the dress and the film and you’ve made something which can go back into the land and not leave a trace, can you say anything about the role of making? The creative act is a kind of way of moving us forward into a new way of being. How can we use this making process, this creative drive that we have as humans to take us in a good direction?

Allan: I’ll jump in there. I mean, one of the things that we learned from growing food on the allotment is it feels like what we give up for convenience, that we can just go down and buy a bag of spuds from the supermarket or whatever, is that what we gain in convenience we lose in all these other aspects. Of being outside, being in the weather, having an intimate relationship with a piece of land, with the creatures in that land, both friend and foe. It’s not always easy, you know, things don’t work. Things fail. It demands a resilience from you. I always say that what I grow on the allotment is symbolic; I’m not feeding myself off that piece of land. Same with the nettle dress. I’m not clothing the whole family in stuff that I’ve made. But it just felt like what those processes give back outweighs what you get from the convenience of just being able to go down the high street and get a cheap piece of clothing, which feels like if it tells a story, it’s probably a story of exploitation and misery. Whereas when you bring home your carrots that you’ve grown, you know exactly what its story is. It’s nourishment is more than just the nutrients. You’ve got so much out of the process of doing it yourself. And that’s really what kind of awoke in me, the whole textile thing, of trying to create clothing, is that wow yeah this is a lot more work than going out to buy it. But what I got from the spinning just emotionally and through a sense of well-being and groundedness was priceless. I mean, I’d feel robbed that I couldn’t play at least some small role in the clothing that I wear, whether it would be even just making the thread to stitch up a hole in a piece of clothing. Like as soon as you fix something or mend something, your relationship to that thing just immediately deepens and it becomes meaningful. It just feels that on so many aspects of our life, we’re just like stones skimming on the surface and we’re just not being allowed to feel the depth of these things. It’s all about cheapness, whereas the slower way of doing things, yeah, sure, you’re going to have far less of them, but your relationship to them is going to be so much deeper. And I think knitters especially, is just how generous knitters are with giving their creations to family and friends, so freely. Like there’s a joy in the actual creation of it; the knitting has been nourishing, and then the fact that someone you love is going to be kept warm and comfortable by your creation. It’s just a whole other depth, which, you know, I really feel that we’re being robbed from. It’s not a convenience it’s a shallowing.

Faith: So if as a culture, we could move from buying and consuming to making even in the smallest way, it must make a difference.

Allan: Definitely.

Faith: And relating to the materials in the way that you related to the nettle. At one point you said that you felt a bit guilty using this last bit of wildness and taming it into a cloth. But I couldn’t help thinking that the nettle had given you in exchange some of its wildness. So it wasn’t lost.

Allan: No, that’s a good point.

Faith: You have that bit of wildness in you. And it’s changed you. You’ve said that in so many ways throughout the film. So it’s a beautiful, beautiful piece of art. And the film is a beautiful piece of art in the same way. And I would encourage anybody who has any creative drive in their body, which I think is almost everyone, to go and see the film. So thank you so much for talking to me as well after doing your conversation with Manda.

Allan: Oh, thank you, Faith, it’s been lovely to chat to you.

Dylan: Thank you. And thanks for saying that, it’s really lovely.

Manda: All righty. So thank you. Thank you both very much for your time. Is there anything else either of you wanted to say? I’m guessing you’re talked out by now, but just checking.

Allan: Oh, just mainly what a thrill and what a joy it has been to chat to you. I do listen to your podcast. I was listening to Alice Holloway’s, who we know and was on our panel when we played at the ritzy and yeah, thank you so much for inviting us on. It’s been an absolute pleasure.

Dylan: Yeah likewise.

Manda: Thank you both

Dylan: And I want to say I didn’t know your podcast, so I’m now going to be digging through your entire archive, which apparently is quite a lot, which is good. You’ve been busy, haven’t you?

Manda: Please don’t feel you have to listen to them all.

Dylan: I did one of your meditations this morning, though, which I absolutely loved.

Manda: All right. Well, thank you both so much. And I sincerely hope we’ll send everyone to watch the film and watch this space. Thank you.

Dylan: Brilliant. Thank you.

Allan: Thank you.

Manda: I said at the top there are links in the show notes. I’ll say it again. There are links in the show notes. accidentalgods.life, and it’s in the podcast section. You can search now, search for nettle dress. You’ll find it. And as I also said at the top, if it isn’t somewhere near enough you and you want it to be, then the distributors are open to finding ways to hold viewings near to where you are. If there’s a small art cinema or something similar and you have contacts and you want to make it happen, then make it happen and get your friends and go and have that joint experience. Alan and Dylan are also open to having a kind of joint Zoom call afterwards and talking about the process, the dress and the making of the film. And it genuinely seems to me that if we’re going to learn how to live in deep time, how to slow down, how to become what we have been and what we can be, then this dress, the making of it, and the film that shows us how it was done are steps on the way.

Manda: Anyway, that’s it for this week. Thank you to Allan, to Dylan, and to Faith for all that they’ve done and all that they are for the wonder of creation and making and emergence and allowing the magic to happen. It’s such a glorious thing to witness. Thanks also to Caro C for the music at the Head and Foot and for the production. Thanks to Anne Thomas and Gill Coombs for the transcripts. Thanks to Faith for the website and the conversations that keep us moving forward. And as ever, an enormous thanks to you for listening. If you know of anybody else who wants to deepen their connection to the land, to being, to making, to the sheer magic of life, then please do send them this link. And that’s it for now. See you next week. Thank you and goodbye.

You may also like these recent podcasts

Still In the Eye of the Storm: Finding Calm and Stable Roots with Dan McTiernan of Being EarthBound

As the only predictable thing is that things are impossible to predict now, how do we find a sense of grounded stability, a sense of safety, a sense of embodied connection to the Web of Life.

Sit with the River, Breathe Sacred Smoke, Love with the World: Building a Bioregional world with Joe Brewer

How can Bioregionalism supplant the nation state as the natural unit of civilisation? Joe Brewer is living, breathing and teaching the ways we can work together with each other and the natural flows of water and life.

Solstice Meditation 2025 – Sun Stands Still – by Manda Scott

Here is a meditation for the shortest night of the year – the time when the sun stands still.

It doesn’t have to be at the moment of the solstice, it’s the connection that counts, the marking of the day. And you don’t have to limit yourself to one pass through – please feel free to explore this more deeply than one single iteration.

Thoughts from the Solstice Edge: Turning the Page on a Dying System with Manda Scott

As we head into the solstice- that moment when the sun stands still—whether you’re in the northern hemisphere where we have the longest day, or the southern, where it’s the longest night—this solstice feels like a moment of transformation.

STAY IN TOUCH

For a regular supply of ideas about humanity's next evolutionary step, insights into the thinking behind some of the podcasts, early updates on the guests we'll be having on the show - AND a free Water visualisation that will guide you through a deep immersion in water connection...sign up here.

(NB: This is a free newsletter - it's not joining up to the Membership! That's a nice, subtle pink button on the 'Join Us' page...)