#181 No More Fairy Stories: Writing the way through, one tale at a time with Denise Baden

We know we have most of the answers to the poly crisis. Our challenge is getting them into the mainstream. And that means we need to understand what works when we craft our new narratives of how the world could look and feel when we make all the right choices from hereon in.

If you’ve listened to this podcast at all recently, you’ll know that I’m in the editing phase of the new book – the phase where we ‘carve it into tiny pieces, throw significant chunks of it in the recycling (because words are never wasted and text storage is basically free) and rebuild the rest into something shinier, sharper and generally more succinct.’ And I’m telling you this because this week’s guest is a fellow writer who knows what it’s like to stare at a blank page until your forehead bleeds – but in this case, she’s also an academic psychologist who has the data to back up the value of Thrutopian writing.

Dr Denise Baden is a Professor of Sustainable Practice at the University of Southampton, and she says, that ‘working in sustainability and climate change, the more you know the scarier it is. Like the sun, you can’t look too closely at it, but face to one side, you make your way, because in fact, it’s easy to put everything right. All the solutions are right here, they just have to catch on. Walking lightly and mindfully upon the earth is so doable. I started writing as therapy, with green solutions as the main ingredient, stories to soothe my soul. Then my characters and their stories took over centre stage, leaving the green solutions to season the stew.’

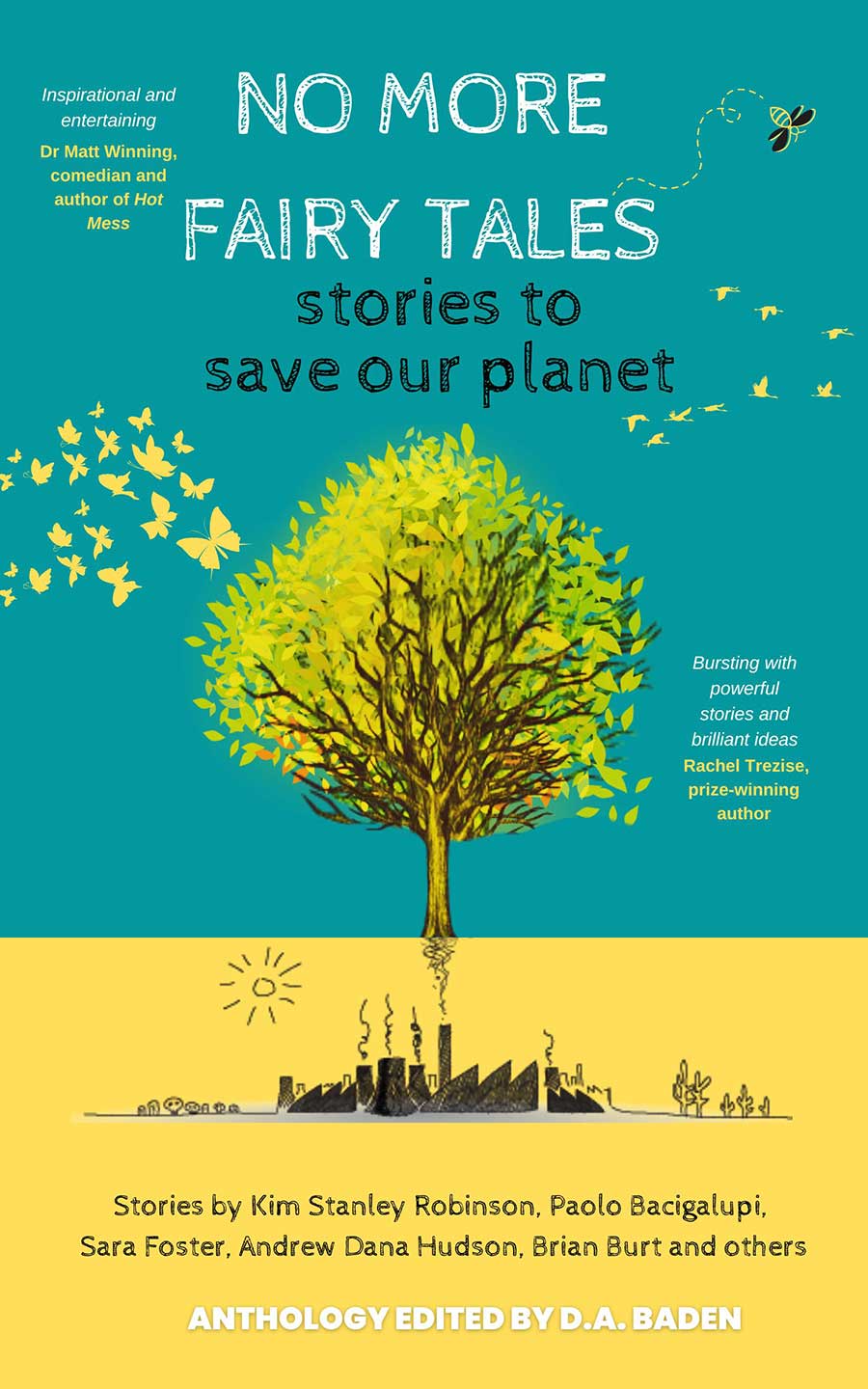

Denise is one of those people who sees a problem and starts creating real world solution. in 2018, she set up the series of free Green Stories writing competitions to inspire writers to create positive visions of what a sustainable society might look like, and to tell stories that showcase solutions, not just problems because her data show that’s what we need. In the process she continued to research what works in terms of fiction and climate communication – as a result of which, she has written a novel, Habitat Man, and she compiled an anthology of short stories called No More Fairy Tales: Stories to Save Our Planet. which she had ready by COP27 so there was a copy for every delegate to read. Magnificently, she is on the Forbes list of Climate Leaders

Episode #181

Links

Denise’s Website

Green Stories website Next novel prize deadline is 26th June

Denise on Twitter

Denise publications and academic record

Sustainable HairCare project

Details of the project with Bafta and Albert

Key hashtags are #ClimateCHaracters and #HotOrNot. The survey is here (please go an complete it!)

The images were designed by Rubber Republic / (check out their website – the first and third especially are hilarious and the one about the old XR protestor is incredibly moving.

Books mentioned by other authors

Carbon Diaries by Saci Lloyd

The Ministry for the Future by Kim Stanley Robinson

In Conversation

Manda: As I might have mentioned once or twice recently, I am in the editing phase of the new book. The bit where you carve it into tiny pieces, throw significant chunks of it in the recycling, because words are never wasted and text storage is basically free, and rebuild the rest into something shinier and sharper and generally more succinct. And then you do it again and again. And I am telling you this because this week’s guest is a fellow writer, so she knows what it’s like to stare at a blank page until your forehead bleeds and then to go through multiple iterations of the editing process. But in this case, she is also an academic psychologist who has the data to back up the value of utopian writing, as you will hear. Denise Baden is a professor of sustainable practice at the University of Southampton, and she says that ‘working in sustainability and climate change, the more you know, the scarier it is. Like the sun, you can’t look too closely at it. But face to one side, you make your way. Because in fact, it’s easy to put everything right; all the solutions are right here, they just have to catch on. Walking lightly and mindfully upon the earth is doable’.

She goes on: ‘I started writing as therapy, with green solutions as the main ingredient. Stories to soothe my soul. Then my characters and their stories took over centre stage, leaving the green solutions to season the stew’. Which strikes me as one of the best ways of getting our stories out there, of getting thrutopian narratives into the world. And Denise is one of life’s people who sees a problem and starts creating real world solutions. In 2018, she set up the series of free green stories writing competitions, to inspire writers to create positive visions of what a sustainable society might look like and to tell stories that showcase solutions, not just problems. Because her data shows that that’s what we need. In the process, as you will also hear, she carried on researching what actually works in terms of fiction and climate communication. And the result of all of that is that she’s written her own book: The Habitat Man. She’s compiled an anthology of short stories called No More Fairy Tales; Stories to Save Our Planet. Which she had ready by Cop27. So there was a copy for every delegate to read. And absolutely magnificently she is on the Forbes list of climate leaders. I am so impressed with all that she is and all that she does. So people of the podcast, please welcome Professor Denise Baden of the University of Southampton.

Denise, welcome to the Accidental Gods podcast. It’s a pleasure to welcome you this sunny afternoon. How are you in Southampton?

Denise: Yes, I’m in Southampton. Delighted to be invited and pleased there’s a little bit of sunshine out the window for a change.

Manda: Yeah, we had enough rain. We needed the rain, but we’ve had enough now. Weather gods listen: a little bit of sun is just fine. Everything here is growing like Fury. May is such an amazing month because you’ve planted all the stuff in April and it just kind of thinks about picking up through the earth. And then my beans are growing several inches a day. I’m just so happy. But the ponies are getting very fat, only out at night. So you have had a very interesting career trajectory. And it seems to me that you are one of the people who really gets what’s going on and that you’re able to bring the weight of academia to bear on the problem, in a way that is practical and intelligent and seems to be bringing other people in. Can you give us a really brief intro to how you came to be the person who set up green stories and wrote Habitat Man and all of the other amazing things that you’ve done?

Denise: Yes, sure. I have had quite a butterfly background, I guess. I went to university a year later than everyone because I wanted to be a bit rebellious and not go, because it was expected. But work was quite boring, so I did go.

Manda: What did you work as? In the boring year.

Denise: Insurance. It was so dull. But I have that taste. You know, everything when you’re a writer is resource material; nothing is wasted. And then I did politics and economics and then went right back in the world of work. First for a non-profit, then for a pharmaceutical industry, then self-employed as a sales rep for book publishers.

Denise: Ooh! Which one? It was Merehurst and Phaidon and New Holland. It’s mostly non-fiction art, cookery, natural history. And then when I had children, it was quite hard to combine that with work. So I went back to do a PhD in psychology. And then I don’t know how I ended up in the business school. It’s a long story, but I did. And I got caught up in teaching business ethics and sustainability simply because I’d nagged them about their lack of recycling. Along the process, I guess I became a bit of a greenie from reading Ben Elton. He wrote quite a lot of fiction. He’s now more screenplays, I think, but he still does fiction. But he was very good at integrating green issues in a very fun mainstream fiction. And I became a bit of a climate activist. Because you know what it’s like, once you’re kind of face to face with the issues, it’s really hard to think, Oh my God, why isn’t everyone running around doing something? So I guess I’ve used my academic background as a bit of a platform to try and engage people. And my whole point is trying to move beyond preaching to the converted. So I’ve done a big project on sustainable hairdressing, using hairdressers to share sustainable advice. And another thing was, people don’t realise how high a carbon footprint haircare can have.

Manda: Some of us do.

Denise: But some people I was amazed, you know, wash your hair, they’ll rinse, repeat, conditioner, rinse, repeat and you know, do that every day.

Manda: And then just keep adding stuff to your perfectly good hair. Yes. And your hairdresser talks to you for however long it takes to do all this stuff to your hair. And they could be talking green stuff. That’s genius.

Denise: Yes. We have these eco tips on mirrors saying, you know, am I shampooing too often? Answer: yes. You know, what about leaving conditioner? Have you tried dry shampoo? Because it’s all about reducing your water footprint really. That’s where the energy cost comes in. You didn’t think we’d be talking about sustainable hair care did you?

Manda: I really didn’t. But this is very good. Yes.

Denise: I like to surprise you. Then another platform I had, because you find out quite a lot about sustainable solutions when you work in the field. And I got so fed up of my articles hardly ever being cited. Like, you know, if you’re really lucky, your article might be read by five, maybe even six people, right? Understood by fewer, when you read the citations. I thought, I need a bigger platform. And so I set up the Green Stories project and the idea of that was trying to encourage writers to kind of smuggle green solutions into stories aimed at the mainstream. And then I did a bit of research and I came to the conclusion, the way we are communicating climate issues, we’ve kind of been doing it all wrong. And I think five years ago this was definitely the case. It was all about catastrophe. The idea was if you scare people enough, then they will give up flying, give up beef. But the fact is, I learned from my psychology experiments, there’s something I don’t know if you’ve heard it, called terror management theory.

Manda: Oh, no. Tell us about that.

Denise: Well, they interview people either in front of a funeral parlour or in front of like a supermarket, and they find that responses when they’re implicitly primed with, say, death, are much more self protective. So there’d be much more likely to vote for anti-immigration policies as a good example.

Manda: Or just to go totally right wing. Yes, Yes.

Denise: So if you scare people, they’re more likely to turn to sort of prepper type behaviour, you know, stocking up their larders, looking after number one, than they are to actually do anything that’s actually going to help. And we think and a lot of writers think and a lot of climate fiction writers think, I want to give my life to making the world a better place. If I tell people how terrible it’s all going to be, if we don’t do anything, they will then behave the way I hope they will. And my research, and I’ve done quite a lot of research on this, shows they won’t know.

Manda: No. It just doesn’t work that way.

Denise: Yeah. Oh, my word, you know, we’re doing it all wrong. And, you know, some people are scared by fear, but a lot of people go to denial, avoidance. So yes.

Manda: So what research have you done? Just can we unpick this a little bit? Because it seems to me this is staringly obvious. Because if it were going to work, it would have worked a long time ago. We’ve had this narrative of things are getting bad. No, guys, things are getting really bad. No, they really, really, really are getting bad guys! For decades now. And, you know, if you go out into the mainstream, business as usual is still the narrative. So what data have you got to support this, let’s stop writing dystopias because it doesn’t work.

Denise: Okay. So I’ve got data from three completely different domains. It started with my business ethics students, when I discovered that the typical way of teaching is to use case studies of business scandals. And the idea is you tell them what went wrong, how terrible that was, and students then won’t do that. But I found that I was showing them how to be unethical in order to gain a competitive advantage. And I thought, that wasn’t my point!

Manda: Whoa.

Denise: So I’d also done some research on whether people who’d done my courses were any more ethical in terms of, say, choosing fair trade products or, you know. No. So I put some in one class, some in another and they all had the same lectures.

Manda: So you did controlled trials on your students?

Denise: A lot of controlled trials, yes.

Manda: Did they know that you were doing this? Did you have an ethical oversight for this?

Denise: I did. I said: I’m doing two types and then halfway through you’ll swap over and I will ask you for your reflections. And some were exposed to your typical case studies of unethical business and some were exposed to sustainable enterprises, you know, ethical business leaders. And I found very clearly that the more positive role models were much more likely to lead to ethical intentions. And then I took that out beyond the student world, and I paid a load of participants and primed them with either unethical or positive role models. And I found there was a distinct effect. And it was mediated, to use the academic term, by cynicism. So showing unethical behaviour makes people cynical. They don’t want to be disadvantaged by being the only one behaving; the sucker effect. And they think it’s less likely you can succeed by being ethical so it leads to less ethical intentions. Whereas if you see someone behaving in an ethical way, you’re inspired. There’s this process called elevation, which is that sense of sort of heart opening you get, when you hear of people doing wonderful things. I mean, your podcast is really good for that. You listen, you think Oh they’ve done wonderful things and you feel you want to do the same. So the positive role models led to much more ethical intentions. I didn’t measure actual behaviour, always a limitation. And then I looked at news, because I thought where are we hearing most of the stuff on the environment? And I looked at news stories, traditional news i.e negative, catastrophic, versus solutions. And again, I found that the more positive, constructive journalism we could call it; made people happier, more positive, more optimistic, more hopeful. The negative ones pessimistic, more anxious, depressed. You’d expect that. Particularly among female respondents, actually.

Manda: Do we know why? Have you got a psychological reason for why?

Denise: Yes, I do, actually. I think generally women demonstrate more empathy. So, you know, when I listen to something terrible going on, I literally feel it myself and that’s unpleasant. So there’s a lot I can’t enjoy on television. I spend a lot of it hiding behind my hands.

Manda: So do men not feel that? Do they not get that twist in the stomach?

Denise: I never like to do, you know, all men this or all women that.

Manda: There’s a spectrum.

Denise: As a spectrum, women are more likely to be more empathetic. Yes. So let’s get back to the news study. So while, you know, people liked positive news, a lot of people would assume that it would be the negative ones that would actually make people act. In fact, whenever I asked people in talks, they always say, yes, the negative ones would prompt me to act. But the results were completely different. When I asked, following this story about the clean up of the oceans, you know, how likely are you to write to your MP about oceans? Take part in a project yourself, contribute to environmental charity, be more environmentally responsible yourself? They were way more likely to say they would, than those who’d watched one of those really powerful programs about plastic in the oceans, which move your heart. I mean, they really do. And that was a surprise. But it replicated what I’d seen in the education one.

Manda: So do you think that’s because the solution based ones give you solutions and the horror stories of, look, here’s a turtle strangling on yet another can wrapper, just doesn’t give you an idea of what you can do. It doesn’t give you a sense of agency or direction. Did you did you kind of loop down into the why of this? Or are we just gathering the data?

Denise: You you hit the nail on the head with the word agency. So if you look at psychological theory, probably the best known theory is the theory of planned behaviour. And that says our behaviour is affected by our attitudes and beliefs, social norms and what they call perceived behavioural control; agency. Can you feel you can make a difference? And pretty well almost all climate communications focus on attitudes, changing your beliefs. So how it might apply to a behaviour might be: recycling. Do you have a positive attitude about it? Social norms. Will people disapprove of you if you don’t or approve of you if you do? And agency: is there a recycling bin available. And the research clearly shows that that sense of agency and social norms are much stronger predictors than attitude. So most climate communications focus on attitude. So, yes, you might show terrible things happening and that increases the belief something should be done. Whether you will do it or not depends much more on social norms. Is it expected to do it and how easy is it to do it? And that’s where we need to focus in. That’s where solution focussed approaches are way more effective.

Manda: Yes. So we have leverage points.

Denise: We do.

Manda: So how do we exert those? Because I’m thinking of seatbelts, smoking, drink driving; all of these have become socially unacceptable in our lifetimes. But we haven’t got very long with this and we are in the middle of a poly crisis. So this is a question. Maybe you have something else you wanted to say first. But the big question that hits me now, is how do we change the social norms so that our actions are in alignment with a flourishing planet? And that’s a really big question. But I think you were about to say something else, so let’s park that question, come back to it.

Denise: No, no. I like a good tangent. I zigzag everywhere. We’ll come back to the third study, but I’ll address your point because it’s a really good one. I think culture has a huge part to play here. So everyone thinks its government policies or regulation or we just switch to renewable energy and everything will be fine. But it’s culture that tells us what’s normal, what we aspire to. And you see that, for example, on TV, on our soap opera characters, our favourite sitcom characters; are they showing behaviours that are really high carbon footprint? What does their behaviour tell you about their implicit attitude towards the planet?

Manda: What’s their framing? Yeah.

Denise: Now for me I am hyper aware of the impacts of my behaviour because it’s my area. I’m not going to criticise people who aren’t. You know, we’re taught not to be aware quite frankly, but because of the world I’m in, I’m very aware. So if I see someone on television ordering, you know, a beef burger. It’s always a beef burger they eat and they’re throwing it away. To me, I think, Well, what’s wrong with the doggy bag? Why can’t anyone eat anything on television? Or if I see wanton destruction or, you know, crazy shopping. To me, I see that connection. So I’m working on a project now with BAFTA and Albert, which is the sustainability wing of BAFTA. And we’ve developed some really fun Instagram images with Rubber Republic, who do such great stuff. They’re so fun. And we’ve tried to make really witty kind of Instagrams, to make that point in a non finger wagging way. So for example, we compare Jack Reacher with James Bond. And you’ve got James Bond with his single use Sports Car, Aston Martin. You’ve got his walk in wardrobe of luxury suits. You’ve got Jack Reacher, he travels everywhere by bus. He only wears second hand clothes. You know, he takes one planet’s worth of resources to kill the bad guys. James Bond, you know, we’d need 20 planets if we all lived like like he does. So we’re sharing them and just trying to start that conversation.

Manda: You make me want to go on Instagram. And I used to share a publicist with Lee Childs, so it’s interesting. He’s not unaware of what he’s doing, for sure. So relatively recently I had a conversation with a friend who writes scripts for soaps and this was actually before lockdown, so it’s not that recently, but even so, it’s within within a reasonable span. And would put in things like the characters taking out the recycling, and it would be written out every single time because, and I quote directly,’our income depends on the advertisers who want everyone to have new granite worktops in their kitchen every year. You cannot do anything to suggest that that’s a bad idea’. So they were aware that that even having a character putting out the recycling, might trigger some kind of awareness and sense of agency in people, such that they wouldn’t throw away their kitchen and buy a new one every year. My friend no longer writes scripts for the soaps. Have you in your work had any sense that the people who were writing that out are beginning to see that maybe that’s not such a wise move?

Denise: Well, there is a big change, I think, in the scriptwriting sector. There’s a real awareness. So Hollywood have got a climate summit now. There’s loads of production companies looking for scripts that incorporate climate solutions. It’s very much on the radar. And I tied a survey to this Instagram campaign to try and get a sense of where the public were at. So we asked them, What do you think? You know, should script writers write what they want? Are we just being boring or do you think actually, it is quite jarring now to be presenting high carbon consumption as aspirational. And so far, no one’s really pushed back on it. People do think, yes, you know, why are they still doing all these travel programmes actively promoting far flung destinations?

Manda: Why does the Guardian have adverts for cruises right next to its, you know, stuff about global heating and how bad it is? And you know, here are some very sad turtles in a faraway place. But never mind. You could go on a cruise there and it would all be fine. Yes. So I want to drill a bit deeper into here, because it seems to me you’re thinking systemically. And yet a lot of the people that I encounter, not necessarily on the podcast but out in the world, are still, I get the impression, looking for the magic bullet that will allow business as usual to continue just with less carbon. And my feeling and I’m assuming you’re understanding too, is this isn’t just a carbon problem. We’re in the middle of a poly crisis and we’re using all of human ingenuity to basically wipe out life on the planet. And simply using less carbon isn’t going to cut it. But that means I would suggest that even Jack Reacher, charming and lovely though he is, he still living in the old paradigm. Are you seeing within Hollywood, within the film industry, an interest not only in writing scripts that are new paradigm (and I’d like to come to what does New paradigm look like) but to change their industry? Because the little tiny bits I’ve been involved with filmmaking, the waste is astonishing.

The only other place I’ve come on anything similar is in hospitals. It’s on an industrial scale. They use things, they throw them away. Whatever the stars want, they will get. Whatever technology you want, Costs hundreds of thousands of pounds, and if it breaks, we throw it away and get a new one. We use a set and we throw it away because it’s actually cheaper to build the next one next time than it is to store it, in case we want to do another series of episodes. It’s catastrophically not regenerative. It’s totally old paradigm. And it strikes me that energetically and emotionally, making scripts that might potentially be heading us in the direction of a new paradigm, making them in the old paradigm way is a bit like everybody smoking while they design the anti-smoking ads. It’s not a good thing. Open to thoughts on that.

Denise: I hope it’s not like that, but it probably is. I know that Albert, which is, like I said, the sustainability wing of BAFTA, they did a talk, just last week. I was there.

Manda: Oh, tell us all about it. Yes, yes.

Denise: Well, I turned up. It’s the media production and Technology show. I turned up to talk about script writing and climate. But then there were three sessions after me, exactly on what you were talking about. On how you can actually do more sustainable production, less resource use, less energy intensive, less waste. So it is happening.

Manda: At least they’re asking the questions.

Denise: And it’s just like more and more festivals, now. Music festivals are being much more aware of waste. I think that is beginning to happen now.

Manda: But Glastonbury, day after Glastonbury, you still see a sea of abandoned tents.

Denise: Well, I know.

Manda: Thinking about it and doing it strike me as not quite the same thing. I mean, I think we’re really close to an edge where thinking about it for very much longer will be too late. It’s like thinking about not driving the bus towards the edge of the cliff, while still stamping your foot on the accelerator. But maybe I’m just having a downer today. Ah, you sound like you get all the great gigs. I’m deeply envious. That sounds fantastic. How did your talk go down?

Denise: Um. Yeah, it went down really well. I went quite subtle, to be honest, because I wasn’t dealing with people who necessarily were climate scriptwriters. They were just normal scriptwriters. And I also don’t think anyone’s going to respond well to the idea that every plot should have characters who are greener than average. I mean, first they want to entertain. But I did say you could at least just not be part of the problem.

Manda: How would you outline that? Because I don’t watch television anymore. So this is hopeless. But let’s say back in the days of, I don’t know, Game of Thrones or Killing Eve, two of the big things that I remember watching when I did watch television. Have you watched Killing Eve? Is that a useful one? So it was exciting and sparkly and it had girl on girl sex, I think that’s grand, but it was an urban thriller essentially, wasn’t it? Predicated on totally old paradigm values of power over and violence wins. Other than perhaps persuading Eve to take out the recycling, I struggle to see how any part of that could be made in a way that moved us forward.

Denise: Well, I gave up watching it once they killed off my favourite character. I was just so upset due to my high empathy.

Manda: Oh, I only watched the first series. So don’t tell me because I might get to watching the rest.

Denise: It was the first series. But I can give examples from ones I know. So the other day I was watching Grace, which is a crime procedural. And there’s a character there every week he sort of solves a mystery. But the overarching plot is that his wife disappeared nine years ago and he doesn’t know if she’s dead. And is he going to register her dead and move on? So he decides he will and he takes her car to the car breakers and he says, smash it up. And they said, well, there’s a lot of life left in this car. It’s hardly been used, you know, no mileage. And he’s so, you know, emotionally delicate, he can’t bear the thought he might see someone driving it. So all that embedded carbon that I agonised over, when thinking, can I justify an EV, You know, it doesn’t bother him. So the implicit assumption there is this is not an issue to be concerned about. It’s so irrelevant, it doesn’t cross his mind.

Manda: Right. So they’re making a plot point about his emotional state using the car as a metaphor. And the the only aspect of that is it was my wife’s, I can’t handle it. So I’m throwing away this memento.

Denise: So that’s what I mean when I say your implicit attitude to nature in the ecology that grounds us will come through, whether you’re oblivious or whether you’re mindful. And I think if we just show mindfulness rather than obliviousness as the norm, that will very subtly but probably quite powerfully shift the way we relate to the world. So it doesn’t have to be signposted, you know, this is a green scene.

Manda: Yes, absolutely. Because that will just put people off. Anyone who isn’t already on board will switch off, because you’re right, it has to be done at a kind of a subliminal level. Is there any psychological work being done on this kind of level of shifting?

Denise: Yeah. So in the field of literary theory, there’s something called narrative transportation. And that is the idea that when you’re reading about a character or watching a character, you are immersed in their world and for a while you see things from their perspective. And that’s one of the wonderful things about reading. You know, you get access to another point of view. And unlike when you’re listening to someone actively, and you’re rationally analysing what they say and seeing if you agree with it, when you’re involved in a character’s story, you just absorb their values as their own. And this can give rise to what they call a sleeper effect. So they kind of persist. So that can be, for better or worse. Does the character, you know, shop like mad, have a walk in wardrobe, you know, waste without thought? Or are they mindful? So you will just absorb those values and they can stick with you in a kind of subliminal way. And I think that is the power of writing, whether it be scriptwriting or writing books, is the ability to invite readers into a different set of values or just reinforce their own values.

Manda: So. Have you looked at explicit and specific examples of this? So I’m thinking Victoria Goddard, The Hands of the Emperor, which I thought was a really beautiful book, and it explored some extremely widespread social concepts like UBI and different ways in which race can be assimilated in a fantasy world. And it was very powerful. It was one of those I think the sleeper effect is like when you wake up after a dream and the dream hangs over through the day. These are the kinds of books where I’m still feeling as I’ve just spoken to these people a few days later. Is that what they mean? First of all, Is that what they mean, and second is anybody looking at whether there is a widespread effect? How would you measure that in psychological terms?

Denise: Yeah, measurement is hard. So there’s been quite a lot of stuff done in the field of what they call cultivation theory, where they look at correlations between how much television you watch and consumer behaviour. And they find that the amount of television you watch correlates with the amount of stuff you buy, and especially if you watch high fashion. And again, then the people who watch that are influenced in their own shopping and behaviour, you know, body image ideas. So there’s quite a lot on TV. When it comes to fiction. Hey Manda, we can come back on the zig zag to what was my third study.

Manda: Oh, your third study? Yes, go for it.

Denise: So I didn’t look so much at the sleeper effect, but I did have people read four lots of short stories. Two were catastrophic and two were solution focussed with a green theme. And I found that the catastrophic ones, a good half of people were switched off by them. They said things like, I felt manipulated or I, you know, I wouldn’t choose to read any more of this or I switched off. Those who were affected in a kind of motivated to do something way, it was quite passive, you know, something should be done. Whereas when I showed characters actually doing something, no one was put off for a start. Apart from one guy who thought it was a bit fluffy, not his cup of tea, but no one was actively put off. Sounding so English, not my cup of tea! No one was actively put off, but they were really inspired. So now I’ve seen this person do this, it made me realise I could do similar. So it went from being a sort of passive despair: Oh, everything’s going terribly. Something should be done, but it probably won’t be. To: Actually, I think I could do this, I might do that, I will do this. So again, over three different types of training; news, education and fiction; they all gave rise to this idea that you need to show solutions and a sense of agency to actively inspire behaviour.

Manda: Brilliant.

Manda: And I think that’s why your podcast is so good, because it’s very much on the solution focuss and I notice you steer people away, you know, when you get too bleak. And we all do that, we all do it.

Manda: But there’s no point. We all know how bad it could be. You know, The Handmaid’s Tale meets The Road. It’s effortless. And I also live in a world, the shamanic world, where where we put our energy is where we get to. So I think it’s actively stupid to do that.

Denise: Water the flowers, not the weeds.

Manda: Yeah. Although I have friends who would say weeds are amazing and we need to raise them. Actually, I think Habitat Man’s thinks weeds are amazing.

Denise: Habitat Man would say that!

Manda: Yes, definitely. So let’s talk a little bit about Habitat Man. Did you write it, having done these studies and then you wanted to write a novel in which a character gives people agency? Because that’s essentially what he’s doing, isn’t it?

Denise: Kind of. I mean, partly it was. I’d set up this green stories writing competitions. We’d run loads of competitions, but I was getting very few stories in that met the criteria, simply because it’s easier to write about things going wrong than right.

Manda: Sure is, so lazy.

Denise: So I thought, well, I’ll write one myself. And round about that time there was this guy locally who’d given up his job, retired early to become a Green Garden consultant. And he came round and he told me where to put a water butt, how to do a pond.

Manda: That’s sounding familiar.

Denise: You know, pollinating plants. And he said, I would love to do the whole world, but I can only do a few gardens. And I thought, Hello, this is a nice idea for a story. So I have him fall in love. I have him dig up a body. A body, then, is a lovely way to introduce the notion of burial.

Manda: A human composting.

Denise: Human composting. So the natural burial scene, actually I was writing that when my mum was dying. So there’s a poignancy to it that I think perhaps comes through. A lot of people wrote to me and they said I’ve actually changed my will to have a natural burial, it sounded so lovely.

Manda: Fantastic.

Denise: And then our English department thought they wanted to do some research on it. And the University of Utah were interested to do some research. So we’ve got 50 people who read it from start to finish. And we sent them a survey a month after, to ask them how it had affected their behaviours. Because I don’t just talk there about wildlife gardening, although that’s key, you know, there’s home composting and so on. But there’s things like one of the lead characters has a dog and I can talk about pet and flea treatments.

Manda: Yes, I noticed it was brilliant. So pleased you did that.

Denise: People don’t know that, do they? A lot of people don’t know.

Manda: Even the vets.

Denise: Aren’t just killing the worms in your dog.

Manda: No. And your flea treatment isn’t just killing fleas. It’s killing everything else. Our local vets have stopped selling the Spot On. But they’re private. It’s a small practice where they own it themselves, whereas most of the local practices are owned by the hedge funds. And the hedge funds are never going to do anything that doesn’t make money. So yeah, that’s cool. Sorry. Carry on.

Denise: I have a sidekick who sets up a random recipe generator. It’s actually a real thing I did with my children once.

Manda: Did you get those recipes? I mean, honestly, I look at those and I think, No, you couldn’t eat that. I’m sorry.

Denise: That one about one of them being a forfeit during games is actually a true story. Um, but yeah, so that’s a nice opportunity because only seasonal food, seasonal low carbon food is on there. And there’s the Joker column, with things like nettles and edible insects. And a lot of people said, you know, that woke them up to the idea of seasonal vegetables and low carbon foods. No one tried edible insects yet, though. The composting toilet as a wonderful metaphor for the circular economy got a lot of mentions. Um, I got into that Glastonbury, I think it was. They’re so much nicer than the other toilets and I’ve got one in my garden. But I thought if my hero has to have a revelation, why not in a composting toilet? So I kind of had some fun ways of working in some of these ideas. So Habitat Man isn’t so much about systemic change, although I guess we do non consumerist values. It’s much more about what can you do in your back garden.

Manda: But I would question that. It felt to me very values based. Tim is an ecologist and he does, I thought, get the systemic stuff. And what he’s doing is doing what people can do locally without badgering them. Which is exactly what you said your psychological surveys; if you go up to someone and go, you’re doing it all wrong. Guess what? They’re not going to listen. But if you can go up and go, hey, look, we could put a pond here and then the frogs will come and look, if you plant some hawthorn instead of your fence, it’ll still give you a visual boundary, but yay, it’s full of pollinators. I thought it was really cool. So it came out in 2021 and you gave these 50 people the questionnaire. What was the outcome then?

Denise: So yeah, I mean, 98% adopted at least one green alternative. So that was really reassuring, exactly what you hope for. What was nice, though, was the textural ones where they said I was going to get Astroturf, but now I realise you don’t have to mow your lawn all the time. It’s better to keep it long. I’ve grown my lawn and you know, things like that. And a lot of them said, talking about that sleeper effect, what the real habitat man (I’m not allowed to say his name) did for me, is he taught me to see my garden in a whole new way. To see it from the perspective, say, of a worm or a bee or a butterfly. And it’s like, you know, when you lift a veil and you suddenly see something differently.

Manda: And you can’t go back, then, that’s the thing. I think it’s one of these one way valves. Once you’ve started seeing like that, you’re never going to go back to the old way.

Denise: It enriched my view of the world. It’s like, if you don’t know anything about art and you go to an art gallery with someone who does, suddenly you can see so much more in a painting. And I really wanted to try and convey that to my readers and get them to see things not from such an anthropocentric way, but from the perspective, the wildlife, the birds and so on. So that was something that came through as well in some of the results. That they’d learned to see their garden in a whole new way.

Manda: So two years down the line, is there any mileage and would you consider and have you considered, going back and asking those same 50 again to see how enduring or durable their changes have been?

Denise: That’s not a bad idea! I’m working on so many other projects at the moment though. But yeah, that would be nice to do.

Manda: Because if you could demonstrate that they had, I don’t know, abandoned the idea of Astroturf for a no mow lawn and then they’d put in a pond and then they’d planted that. And they’d got their neighbours to do it. Because we find, some of my Accidental Gods students in the UK and the US have gone for the the no mow, let’s just not mow. But particularly in the US, the neighbourhood watch, whatever it’s called, I forget. Sorry American people, but it sounds like the local stormtroopers basically, get incredibly upset if you don’t have the white picket fence and your lawn at the requisite quarter of a millimetre length. But if you put a sign in there saying, I think the American one is Home-grown National Park, or in the UK, it’s We are the Ark. Then it becomes a talking point and then you can discuss it. And then 2 or 3 years down the line, other people are doing the same. And so that would be interesting, is what’s the R number? How much does this spread? Because it seems to me if we can get an R number greater than one, as in viral spread, of thinking about your garden from the perspective of a butterfly or a worm, then we’re on to change that will be durable and will expand.

Denise: That’s a nice point about putting a note to say what you’re doing. Because I emailed the council saying please can you not mow the borders? Just let the dandelions grow, the nettles grow, they’re good habitats and please don’t use pesticides, you know, let’s go pesticide free. And they wrote back saying the thing is, people complain. I said, well just put a little note saying we’re doing this for wildlife. For example, in our local sort of website forum, someone was complaining and someone said, No, they do that for the habitats. And they said, Oh, well, that’s brilliant. I thought they were trying to save money or just being lazy.

Manda: And the fact that they do save money as well is an added bonus. We’ve got something called RSVP, Rural Shropshire Verges project, and I drove down a particular lane this morning and there is a great big, like a road sign, saying this verge is not to be mown until August. You know, being kept. And I don’t think the council put that there. I think the project put that there. But it does mean that even if the farmers are getting a little bit, you know, trigger happy with their tractor and their mowers, they’d have to actually mow over this sign or try and pull it out of the ground, to get to the verge.

Denise: Just education, isn’t it really.

Manda: Yeah. Exactly that. I’m trying locally to just persuade everybody that they must not buy Roundup. Just don’t buy it. And then my next move is to get to the local shops and go, Please don’t sell it. Just stop selling Roundup.

Denise: I’m really worried about pesticides.

Manda: Yeah. If we wanted to wipe out the entirety of the biosphere, then the product of Monsanto is pretty much how we’re going to do it. And we don’t need it. And countering the narrative that the only way to feed the planet is by industrial farming, for instance, which is manifestly untrue, needs to be expanded. That’s a whole other sidetrack. Let’s not go down there. Let’s come back to your work, your writing. I love the fact that you’re actually gathering evidence base for what you’re doing. And you said you’re really busy and there’s other things that you’re involved in. So what are you doing along these lines just now?

Denise: Well, last year’s project, which has given rise to what I’m doing now, is an anthology where we we put together experienced writers like Kim Stanley Robinson, who did Ministry for the Future, and Paolo Bacigalupi, Sarah Foster, with Climate Experts. And we compiled 24 short stories that had transformative climate solutions at their heart. And they’re really engaging stories. Some are like comedies, some are romances, some are action, some are family dramas. Some are very poetic and lyrical. Others are very informationy, you know, dry for the techies. And they encounter, you know, nature based ones, more carbon capture, technical ones, more systemic ones. So all approaches, really. Yeah.

Manda: And Kim Stanley Robinson gave you a bit of his book, which I was really impressed with. The bit about the carbon currency, which is brilliantly worked out, very impressed.

Denise: So it’s called No More Fairy Tales; Stories to Save Our Planet. And we managed to get it ready in time for Cop27 and they shared it there. It was all a bit last minute, but we just about got it ready and each story links to a website. And if you think, okay, I love the solutions in that, I want to help make them happen, you can click on that and we show what you can do at the individual level. If you’re a business, if you’re a funder, a government and so on. So trying to actually sort of get some engagement and harness that energy, from reading it, into actual solutions.

Manda: And what have been the responses to that? Because you handed this out at COP, didn’t you? So did you get much feedback then? And have you had much feedback or chance to do studies since?

Denise: Yes. So part of the reason the writers were so keen to get involved is I think a lot of us write as therapy. We think if we can write the solutions, maybe they will happen. And we had a couple of stories that sort of showcased the idea of the ocean as nation. What if we gave nation status to the ocean? At the moment, you can pretty well do what you want as long as it’s not a marine protected area. No one’s going to tell you off, even if it’s massively destructive. What if you couldn’t do that? Or what if you had to pay to travel across or take the oceans resources and that money then could be fed into seagrass restoration, kelp restoration and so on. Giving nation status or legal status to nature is an incredibly effective solution. So one of the guys, Steve Willis, he was one of the sort of energy forces behind the anthology. And he put this idea forward and we had a number of authors working on it, and he was at the Pan Asian Ocean Summit last year, soon after that. And he got a lot of traction. A lot of people were interested. And our own head of law, University of Southampton, said this isn’t actually a bad idea. And they put it on the agenda to talk about at the next Ocean Summit. So it started the conversation. I don’t know if it will ever happen, but it certainly did inspire conversations around that theme. It probably won’t happen like it does in the story.

Manda: But the idea is out there and seeded. I think this is what inspires me so much about what you’re doing, is that you’re getting ideas out there and you’re right, it might not be exactly that, but the only way we’re going to break the current paradigm is if people see that there are alternatives. I think a lot of the reason that our ruling classes do nothing is because they have no idea what could be done other than what Steve Bannon feeds them, which is not where we want to go. But if they if they had a vision for a future that would work, that touched them in whatever lump of lead passes for a heart… Yes, that was terribly judgemental. But still, I’ve been watching the Nat-C Conference. I cannot believe that these people are standing up and talking. It’s something that’s called Nat hyphen C and they don’t think that’s a problem. Anyway. If they were given solutions that seemed to work within their framing and that we felt worked within a wider framing, it’s not impossible they would do it.

Denise: I also think that there’s a freedom in fiction. You can paint a picture and some of the ideas can be quite complicated and it’s quite hard for people to remember facts, but if you if you couch it in a story, it’s much more memorable, much more easy to understand. So, for example, one of the solutions we talk about is personal carbon trading or personal carbon allowances. And that was an idea that was proposed by DEFRA, the Sustainable Round Table, back in 2007. David Miliband, do you remember him? Was talking about a credit card and people were getting quite excited about this idea that we would have our own personal carbon allowance. And what I loved about that was at the moment, I don’t know about you, but I spend a lot of my time feeling guilty for what I’m doing or seething with resentment because I’ve given up something I really love. But everyone else is busy flying off here or there and eating steak and it’s not pleasant to be moving from guilt to resentment and back. But if we all had our own personal carbon allowance that you were responsible for, that is fair, that is equitable. And if you went under, by being ever so green and good, you could then sell your spare carbon credits and make a ton of money. Great. If you went over, will you pay through the nose to get some more? Fine. You are paying for your impact on the planet, whereas at the moment there’s very little incentive to be honest, other than your values, to go green.

Manda: Okay, I wish we’d started with this. First of all, if you haven’t read The Carbon Diaries by Saki Lloyd, they came out in 2015, definitely worth reading those. They’re young adult books, but they’re brilliant. I will link them in the show notes. However, you and I both understand that carbon alone is not the problem. That’s point one. Point two is, I’m quite involved in pasture fed livestock association, regenerative farming as a whole. In looking at how far along the chain do you go to estimate carbon? Because the only way that people like Monbiot get their precision fermentation of proteins as in any way ‘sustainable’, and the word sustainable is doing a lot of work there and most of it is fake is because they’re not counting all the way up the chain. The whole let’s eat vegan only works if you don’t count the impact at every level of industrial farming. And you have to count the fact, for instance, that if you put nitrogen on the land in whatever form you put it, urea, ammonia, whatever, most of it will combine with atmospheric oxygen and create one of the oxides of nitrogen, which is monumentally more global warming impact than carbon dioxide. You’d have to count all of that. And it seems to me that could be done. We do have the computing power for that now. The overwhelm of that would be huge. And the realisation (I’m trying to remember who it is that said this, I will dig it out in a bit) that nothing that we have in the Western world just now is valued at its genuine value. You’d have to increase the prices of absolutely everything if we were going to really cost them at their actual cost, instead of simply dumping stuff into the oceans or the atmosphere or the ground, or enslaving people in other countries on wages that are completely not liveable. How does the idea of carbon credits pan out in a Western society that’s still basically in denial about the realities of the impact of how we live?

Denise: Right. Oh, there’s a lot to unpack there Manda.

Manda: Sorry there is, but you can do it. I haven’t met many people who’ve got the depth, so go for it Denise.

Denise: Okay, let’s try. Well, a lot of the points you make are the reason why it didn’t take off back in 2007. It was an idea ahead of its time, so it required us to be scared enough to do it and we weren’t. And it required a level of carbon footprint technology and calculations we didn’t have. Now we are scared enough and we do have that carbon footprint. Not perfect. But you can’t let perfect be the enemy of the better.

Manda: Absolutely.

Denise: And I think if I was going to introduce it, you would start small. You would start perhaps just with your energy, with your fuel. At the moment, when we pay for energy, it’s quite expensive for the first bit we consume and then it gets cheaper. It should be completely the other way around. Because the moment you increase the cost of energy, you know, you’ve got people shivering and dying from cold and fuel poverty. Well, if you make the first essential bit really cheap and then make everything above that expensive, you inverse it. And that’s kind of what personal carbon allowances would do effectively.

Manda: But even just on heating, you would have to actually have a program to insulate everybody’s houses before that was in any way equitable. And then how do we get around the transport? So a lot of our current fossil fuel use: huge amounts in manufacturing, huge amounts in agriculture. And then transport: both transport of goods and materials and then transport of people, and then heating. Each of those strikes me that the people with lots of money will just carry on having their private jets, and the people with not very much money will end up having quite a lot less money if we don’t build equity into the system. How does your system build equity in?

Denise: Well, let’s start from the position now: we have no equity at all.

Manda: That’s true. Yes. Yes. I’m not suggesting the current system is working. At all.

Denise: And the rich can trash the planet with no consequence.

Manda: Yep, true.

Denise: Okay. That’s where we’re starting from. Personal carbon allowances act like a kind of ration. So, like in wartime, when certain things were short, you would only be allowed so much of that. So if we think of carbon emissions or equivalent, which takes into account nitrous oxide and ethane and so on. If you take that and you ration that, then most people who are close to the poverty line, the sort of lower income people would be better off. They estimated 71% of them would be better off under that system, because they would be consuming less than their carbon allowance and they could sell their spare credits. So those who were consuming more, it’s kind of like a progressive form of taxation. And what it would do is it would funnel investment into low carbon products. So for example, I could buy milk that’s been grown in a regenerative sustainable farm and it uses up fewer carbon credits than the milk that’s been produced differently. People might still want to fly, but it uses up their entire carbon allowance. If you want a sustainable aviation fuel that’s suffering from lack of investment, investment would pour into it, you can be sure of that. So it would harness our own consumer behaviour to seek out low carbon alternatives. Why would we ever have flown in asparagus or flown in beans, when they use ten times the carbon allowance of what’s in season? At the moment there’s no difference in price, so it’s not really on our radar. Supermarkets would start labelling that, because it would matter to us. So the price and the carbon cost would be almost equally important to us and it would be quite bureaucratic. The more careful we were to get the carbon calculations correct, the more work it would be. But even done in the broadest possible strokes, it would be a hell of an improvement and funnel our own behaviour and innovation towards a low carbon economy.

Manda: It’s brilliant.

Denise: Do I have a convert?

Manda: Yeah. Well, you have the beginnings of a convert, because I’m also reading Robert Lustig’s book Metabolical, which is just blowing my mind. And 93% of Americans have metabolic disease and it’s because of the food industry which subsidises corn growing and then produces corn syrup and everything is flooded with fructose and it’s completely destroying the nation’s health. I don’t think ours is any better. So and industrial farming is going to be very carbon credit heavy. Regenerative farming, potentially done the right way, not the let’s spray the fields with glyphosate, but not plough them way. Proper regenerative farming is going to be much more carbon light. I’m not sure I want anyone devising a fossil free airline fuel because I just think flying has to stop. I think on every level it’s not a good thing. But yes, what this makes me think of is there was an incident in ancient Rome. And the thing you have to remember about ancient Rome is that they all drank their wine that was warmed in lead vessels. So the entire upper class had chronic low grade lead poisoning, which excuses or at least explains, it doesn’t excuse anything, explains a lot.

Manda: And one of the less bright, chinless wonders in the Roman Senate decided it would be a jolly good idea to get all the slaves to wear armbands so that you could see that they were slaves. And the slightly more switched on ones went, How many slaves have you got? And they’re going, oh, I don’t know, three, four, five hundred. And they’re going, the average is 500 per senator. So I want you to imagine going out into the forum and there being 500 to 1 of people who realise that there’s 500 to 1. How long do you think we’re going to last? And the idea was dropped instantly. And so it seems to me that carbon credits is a bit like, Oh, okay guys, let’s just give everybody the chance to see who’s blowing everything and who isn’t, and see how long the people who are blowing everything get to carry on blowing everything. It would be putting numbers on conspicuous consumption in ways that currently we don’t quite have. I think it would be amazing. I would be really surprised if the masters of the universe who rule over us at the moment would ever entertain the idea.

Denise: So this this leads nicely on to my latest project. Yay!

Manda: Oh, that was a neat segway.

Denise: Completely by accident. But as we discussed, it took a little bit of explaining, didn’t it, to get the concept over.

Manda: All of my yes buts. Sorry but yeah.

Denise: But I mean they are obvious questions you would ask. It’s a difficult concept to raise awareness of. It’s not something a politician can do in a soundbite. It’s something the right wing reactionaries would easily throw mud at. So fiction is a really nice way, it’s a safe space, to introduce these kinds of ideas. So my favourite story in terms of impact, in No More Fairy Tales; Stories to Save the Planet, was The Assassin. Which is set in a citizens assembly where eight people meet to debate climate solutions and one of them is an assassin, just to give it a bit of fun, a bit of whodunit. And they talk about things like a repair ville. And the point is, well, we have repair cafes and right to repair. Doesn’t mean anyone would, too easy to buy new. We have things like the sharing economy, libraries of things, tool libraries. And it’s like, well, I’ve got a library, I can borrow books, but I still buy them new. There’s not enough uptake. We have things like on demand transport, because we know we can’t all just have electric cars. There’s not enough lithium for a start. You know, if you had super public transport with buses that came when you called them and everyone signed up, so it was massively cheap and efficient and went everywhere, who would want your own car? It’d be like living in London. No one has a car in London.

Denise: But again, people won’t sign up because they want their own car. And the personal carbon allowance solves all those problems, because the moment you have that, all these other great ideas suddenly can take off. And these ideas that are massively convenient. Who wants to have everything? All your tools and bread bins and cycle racks and tennis rackets hogging up all your space. If you could just go to a local library of things and borrow it and know you could get access, who would want the burden of ownership of the car if you could get great public transport? So personal carbon allowance is a great way and these are the solutions debated in the citizens assembly. But the biggest solution of all is that democratic process. Because like you said, no government is going to vote for it. Governments, as we’ve seen, it’s empirically shown; we’ve known about the climate crisis for 40 years now. No representative democracy has made even close to the amount of regulations and climate policies that they need to, because a four year electoral cycle, they’re always going to prioritise short term goals over long term existential threats.

Manda: And the lobby ensures that we have the best democracy money can buy. It’s a wholly corrupt system.

Denise: You’ve got the whole vested interests as well. You’ve got the fact that people there don’t represent the population. Citizens assemblies have been shown to make really considered and sustainable decisions. You’re looking doubtful.

Manda: Well, I am looking doubtful in that I was really impressed with the citizens assemblies in Ireland. Gay marriage and the right to have an abortion, absolutely really impressed. I was deeply under impressed with the citizens assembly that the UK Parliament, not the government, convened. Because it seemed to me that the people in there were not given access to the kind of data that they would have needed to make an actual considered concept. And that citizens assemblies are fantastic provided the people within them are adequately informed. And how do we know, particularly as we’re entering the era where AI is going to be able to create fake facts within the next year. Learning to trust what you’re giving to your citizens assembly, so that you can trust the decisions that they make, strikes me as one of the very, very big questions of our time. Is this something that you’re looking at and have you got ideas?

Denise: Well, information is key. I’d say pretty well most of the big decisions over the last decade, not just in the UK but internationally, have been made on the basis of misinformation. Most referendums, political decisions have been made on the basis of either partial or misinformation. So again, the bar is low. But the idea behind citizens assemblies is: 1. The people there will represent the society, in terms of gender and class and education and religion and and ethnicity and so on. So they’re way more representative. 2. A variety of stakeholders relevant to that topic will present information. And like you say, that’s crucial, what information they have access to. And so there’s a learning phase, there’s a deliberation phase, and they tend to work in tables of about eight with a chair whose job it is to ensure that everyone gets a fair sort of chance to speak their turn. And they come up with recommendations. And this is where it falls down. Their recommendations have generally been very good, but it’s up to the governments whether they decide to accept them. I think in France they have more actual power. And in cities like Gdansk in Poland, they really got tons of great policy through.

Denise: So they have been shown to have real power in some places. But certainly in the UK it’s been advice only and that’s what’s held them back. So my next project is a play. I’ve adapted The Assassin as a play called Murder in the Citizens Jury. And the issue is, if they actually report the murder, will it bring down citizens juries? So this is the first one which has actual power. And the very reporting of the murder itself could bring down what they think is going to be the silver bullet to help us make good decisions. And so there’s a crisis of conscience and it’s interactive. The audience then have to vote. Are we going to prosecute?

Manda: Oh, wow.

Denise: So it’s kind of fun. I get the audience to vote on the climate solutions debated and whether or not to prosecute the murder. I had a promise it will be shown at COP 28. But I’m still trying to do a read through of the first draft and make sure it works properly.

Manda: And are you working with the dramatist?

Denise: I worked with Naomi Elster, she’s written some plays and she actually was on the Northern Ireland Citizen’s Assembly.

Manda: Fantastic. Right. So she has inside information. Fantastic.

Denise: She knows about climate communication and health communication. So she helped me sort of take it from the book stage to a play stage. And then it was back in my hands to kind of fiddle around with it. And I’m still fiddling around with it.

Manda: It strikes me that this could also be television. I don’t know how you get the voting, but I know they do voting for, I don’t know, online television game stuff. So this could be a play for today kind of style television, or it could just be adapted as a TV script and then you would get much wider viewing.

Denise: Any producers out there? Yes, please.

Manda: Well, maybe do it as a play and then we can just try and spin it to anyone. I mean, obviously, Hollywood Climate Forum would presumably be interested. It’s worth a try. Get it done as a play first. Get people to see it. If it’s at the next COP, then hopefully somebody will be there watching. That sounds really exciting. Gosh, and time. How did the time go so fast? This just feels so exciting. So I have one last question. I remember quite a long time ago, Neil Gaiman gave a speech in London somewhere, where he said that he was talking to the people who built prisons in America, because prisons are private and you don’t make any money if you either have too few cells or too more. And he was asking them, How do you know how big to make your prisons? And they said there was an inverse relationship between the number of young men who ended up in prison, and the percentage who were reading books by the age of 12. So more young men reading books by age of 12, fewer young men in prison five, six, seven, ten years later. And that’s, I think, now at least ten years old, that work. And I’m wondering if there’s any work that you’re aware of, correlating reading now. Because social media didn’t exist back then. The attention harvesting of humanity was not such a big thing. How is reading going down now? Is it only those of us who read as kids and who are, you know, demographic churn is going to take us out in the next 20 years? Or are young people reading books in increasing numbers? Or do we not know?

Denise: I don’t know. I mean, I hear bits and pieces. So I hear that Booktok is doing quite a lot to encourage young readers.

Manda: I didn’t even know Booktok existed. Okay.

Denise: That’s sort of part of the whole TikTok thing. And you do get what they call whale readers, who tend to just read huge amounts of genre fiction. So they sign up for Kindle Unlimited and they will just, you know, consume large amounts of either romances or thrillers or fantasy or whatever the genre.

Manda: I think I’m probably a whale reader. Oh dear.

Denise: But I don’t have the stats. But what you said about Neil Gaiman doesn’t surprise me at all.

Manda: It’s that the capacity to empathise that you were talking about at the start. That capacity to to step into a world. If the writer has done it well enough, you are that person, whoever’s viewpoint you’re seeing.

Denise: Audiobooks I think are providing a whole new way for people to access books. So for those who actually don’t like to sit down and read, I mean, everywhere you go now, people have got their headphones on, listening to audiobooks, podcasts, music. So I think, yes, it’s still going on, but perhaps in different ways.

Manda: Okay, that’s heartening to know. I certainly know in the publishing world, audiobooks are now a major stream along with ebooks, obviously. And it’s good to know that when you see people with earphones in, they’re not all just listening to the horrible dopamine hit of canned music, which personally I think should be banned. But I know it’s everybody’s deepest addiction and they really hate it when I suggest that. Is there anything else that you would like to share with the audience? Because this has felt so rich and so inspiring?

Denise: No, it’s been really nice. You forced me to think through a lot of things. I’ve been properly drilled in the relationship between academic research and what I’m doing. But I think the key points I wanted to get across, I guess, are that writing is a nice way to kind of visualise how something might work in practice. And to play with quite transformative ideas such as what if we had personal carbon allowances. And you said The Carbon Diaries. It shows it in a sort of young adult, coming of age story, doesn’t it? A little bit dystopian, they’re certainly not something anyone likes. But yeah, nicely done. So I would like to mention I’ve got green stories writing competitions coming up all the time.

Manda: Yeah, we’ll put a link in the show notes to that website and it’s short stories and novels and other formats.

Denise: Well, it depends on our sponsors. So if anyone wants to sponsor some more, that’s great. But at the moment we’ve got a novel prize coming up in June and we’ve got a short story prize, it’s quite a techie one for more science people. I expect we’ll have more again in the future. So people want to keep an eye on the Green Stories website. They’re all free to enter, and as long as they’re in English really.

Manda: I will definitely put a link in the show notes. Denise, Thank you. This has been so inspiring. I will link also to Habitat Man and to No More Fairy Stories and to your own website. So if there’s anywhere else that you think we should know about, let me know.

Denise: One more. Yes. So that campaign I said with BAFTA, if you check out #ClimateCharacters or #hotornot, you’ll see some of those fun Instagrams. And I do encourage you to take the survey, because we include a link to the survey as well.

Manda: Are they on Twitter?

Denise: Yeah they’re on Twitter as well.

Manda: And then we just need Mastodon, which is the nice version of Twitter and doesn’t involve engaging with Elon Musk. Brilliant, Fantastic. Denise this has been so inspiring and right up my street. Basically you’re a Thrutopian, long before I was. So I’m deeply, deeply happy to have spoken to you and so glad that there’s academic work being done to demonstrate what things work. Because we’re beyond the stage of just guessing what might work. We need to know what actually works. So thank you for doing all of the studies on that. It’s grand. I think probably give it a year and we’ll have you back and see what you’ve got to with with your play and with whatever studies you’ve done in the interim.

Denise: Well, thank you so much for inviting me. I love your guests. They’re always so inspiring. So I’m absolutely honoured to count myself among their number now.

Manda: Fantastic. Mutual Appreciation Society. That’s the way we like it. Thank you. And we’ll talk to you again sometime.

Denise: Take care. Bye bye.

Manda: And that’s it for this week. Enormous thanks to Denise for all that she is and does. This felt so inspiring to know that there’s somebody else who gets it, who’s really looking at the data and is able to produce hard numbers to show people that dystopian writing is not useful. I am kind of thinking utopian writing is probably not useful as well, and there may be data to prove that, and I didn’t think to ask, so I’m going to ask Denise offline. But in the meantime, if you have any voice in the world at all, from Twitter to TikTok to Instagram to Facebook to columns in the parish post or your local equivalent. Local newspapers, local radio to the bigger stuff; BBC, Channel four, CNN, whatever is in your country. Please begin to develop concepts of what will work, of what will actually touch people. Because we know now that simply saying you’re wrong and everything’s falling apart does not work. What works, as Denise so clearly said, is giving people a sense of agency and creating that social legitimacy around what we’re doing. If you have any way of doing that, I think it’s one of the single most important actions that we can take. And if you’re writing a novel that has Thrutopian themes, please go and look at greenstories.org.uk and look at the writing competitions. The novel prize is still open. The deadline is the 26th of June. All of the instructions are there and it’s free to enter. So give it a go. Why not? And if you aren’t writing something yet, get on and write something! You’ve got a whole month. You can write thousands of words in a month. Trust me on this. And if there is an appetite out there for specifically through thrutopian writing tutorials, online work, I might be open to that.

Manda: I am not, I’m sorry, open to reading everybody’s individual stuff. I absolutely haven’t got the time. But if we wanted to come together on a regular basis and simply talk through the ideas of the ideas and basic principles of writing, then I would be open to that. So I don’t know if people want that, or if it would be useful. I have a tendency to think there’s an awful lot of how to write stuff already online, and it’s probably not a useful use of my time and emotional energy to create more. But if we specifically want to talk about writing through thrutopian stuff and the actual mechanics of that, which is not what the thrutopia.life is about. That’s about the content, not the mechanics. If we want to look at mechanics, then I would be up for that. So let me know: manda@accidentalgods.life.

Manda: And in the meantime, enormous thanks as ever to Caro C for the music at the head and foot and for the hours that she puts into the production of these podcasts. To Faith Tilleray for designing the website, for keeping it beautiful, and for the conversations that keep us moving forward. To Anne Thomas for wrestling with the transcripts, which some weeks is harder than others. And as ever, to you for continuing to listen, for engaging, for caring about the things that really do matter. And if you know of anybody else who wants to be inspired by the power of story to change the world, then please do send them this link. And that’s it for now. See you next week. Thank you and goodbye.

You may also like these recent podcasts

Sit with the River, Breathe Sacred Smoke, Love with the World: Building a Bioregional world with Joe Brewer

How can Bioregionalism supplant the nation state as the natural unit of civilisation? Joe Brewer is living, breathing and teaching the ways we can work together with each other and the natural flows of water and life.

Solstice Meditation 2025 – Sun Stands Still – by Manda Scott

Here is a meditation for the shortest night of the year – the time when the sun stands still.

It doesn’t have to be at the moment of the solstice, it’s the connection that counts, the marking of the day. And you don’t have to limit yourself to one pass through – please feel free to explore this more deeply than one single iteration.

Thoughts from the Solstice Edge: Turning the Page on a Dying System with Manda Scott

As we head into the solstice- that moment when the sun stands still—whether you’re in the northern hemisphere where we have the longest day, or the southern, where it’s the longest night—this solstice feels like a moment of transformation.

Falling in Love with the Future – with author, musician, podcaster and futurenaut, Rob Hopkins

We need all 8 billion of us to Fall in Love with a Future we’d be proud to leave to the generations that come after us. So how do we do it?

STAY IN TOUCH

For a regular supply of ideas about humanity's next evolutionary step, insights into the thinking behind some of the podcasts, early updates on the guests we'll be having on the show - AND a free Water visualisation that will guide you through a deep immersion in water connection...sign up here.

(NB: This is a free newsletter - it's not joining up to the Membership! That's a nice, subtle pink button on the 'Join Us' page...)