#195 Spiritual Activism: Permaculture of land, heart and people with Maddy Harland

Permaculture is so much more than simply a way to connect people to the land and the growing of food: it’s a way we can bring all of ourselves to the project of total systemic change: our minds, bodies, spirits, hearts – and the practicality of what we do.

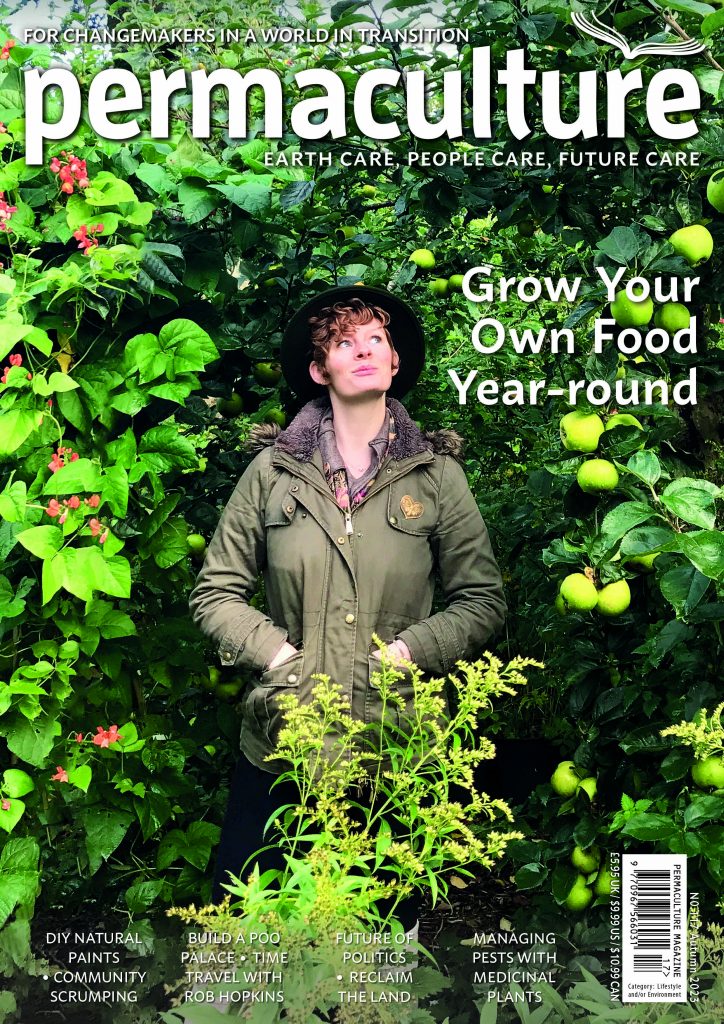

This podcast is focussed on all the ways that we can bring all of ourselves to the project of total systemic change: our minds, bodies, spirits, hearts – and the practicality of what we do. Given this, we’re delighted to welcome to the podcast Maddy Harland, the Co-founder and Editor of Permaculture Magazine .

Maddy, and her husband Tim, co-founded a publishing company, Permanent Publications, in 1990 and Permaculture Magazine in 1992 to explore traditional and new ways of living in greater harmony with the Earth. She is the author of Fertile Edges—regenerating land, culture and hope and The Biotime Log.

Maddy and Tim, have designed and planted one of the oldest forest gardens in Britain: once a bare field, it is now an edible landscape ,a haven for wildlife, and a reservoir of biodiversity. I met Maddy first back in the early days of this millennium when the whole Permaculture team was in the south east of England. More recently, they moved to Devon in the south west, where they are retrofitting a Devon longhouse to become zero carbon and restoring an old woodland to be a sanctuary for rare species like Dormice and Pied Flyctachers – and to be a place of healing and retreat for people.

Maddy has been one of the beacons of the regenerative movement for decades. She’s edited one of the world’s most vibrantly alive magazines for over thirty years, she’s interviewed – and edited – everyone who is anyone in this field from Vandana Shiva to Satish Kumar to Patrick Whitefield hundreds, literally, of the less well known, but absolutely cutting edge, inspiring people in all corners of the world who are living the change that will take us to the future we’d be proud to leave behind.

If anyone knows where we’re at, and what potential there is for change, she does. So it was a joy to be able to connect and explore ideas with someone who’s given their life’s energy to exploring the ways that change can happen.

Episode #195

DISCOUNT COUPON

PERMACULTUREGODS

With this, you’ll get a free copy of Maddy’s book Fertile Edges, with your subscription. Please use the code at the Checkout. (NB: this is valid until 23:59 on 6th November 2023 – and works once a subscription and Fertile Edges have been added to the cart, and then the code added).

Links

In Conversation

Manda: Hey people, welcome to Accidental Gods. To the podcast where we believe that another world is still possible and that if we all work together, there is time to create the future that we would be proud to leave to the generations that come after us. I’m Manda Scott, your host in this journey into possibility. And this week I am genuinely delighted to welcome to the podcast Maddy Harland, the co-founder and editor of Permaculture magazine. Maddy and her husband Tim co-founded a publishing company, Permanent Publications, in 1990. And as you’ll hear, they began to publish Permaculture magazine in 1992 to explore traditional and new ways of living in greater harmony with the Earth. She’s the author of Fertile Edges Regenerating Land, Culture and Hope and the Biotime Log. Maddy and Tim are not just into publishing. They designed and planted one of the oldest forest gardens in Britain. Once a bare field, it’s now an edible landscape, a haven for wildlife and a reservoir of biodiversity. Everything that they do is rooted in all of the permaculture design principles and the ethos of connecting back to the land. I met Maddy when I took a permaculture course way back in the early days of this millennium, when the whole permaculture team was then in the south east of England. More recently, they moved to Devon in the south west, where they retrofitted a Devon longhouse to become zero carbon and restoring an old woodland to be a sanctuary for rare species like dormice and pied flycatchers, and to be a place of healing and retreat for people. Maddy’s been one of the beacons of the regenerative movement for decades.

She’s been, as we said, the editor of Permaculture magazine, which is one of the most vibrantly alive magazines in this field for over 30 years. That means she’s read every article she’s commissioned, every article she’s interviewed and edited everyone who is anyone in this field. From Vandana Shiva to Satish Kumar to Patrick Whitefield, and hundreds literally of less well known, but absolutely cutting edge, inspiring people across the world who are living the change that will take us to the future that we would be proud to leave behind. So if anyone knows where we’re at and what potential there is for change, she does. So people of the podcast, please welcome Maddy Harland of Permaculture magazine and Permanent publications. And if you wait until the very end, we have a special coupon for you that will give you a free gift when you subscribe to the magazine. Here we go:.

Maddy, welcome to the Accidental Gods podcast. It is such a delight to have you here. You’ve been one of my superheroes of changing the world since I came to visit you in Hampshire some time in the very early years of the millennium, when permaculture was still to me, a new idea. So I would like to wind us back to the beginnings of Permaculture magazine, which is going to hit its 30th birthday soon. And you are co-founder and editor and you’ve been doing it for very nearly 120 editions ever since. Tell us how you came to be the person who started what is now part of a worldwide thriving movement.

Maddy: So in the early 90s, we watched a film called In Grave Danger of Falling Food, and it was all about a man called Bill Mollison, and it predicted a biodiversity loss, particularly caused by industrial agriculture. And it also looked at peak oil and escalating oil prices and the oil crisis as it was called in around that time in the 80s. And we looked at it and we were really focussed on conservation at that time and really interested in wildflower meadows and biodiversity and all the basic create habitats for wildlife. Because we could see that there was crashing wildlife populations at that time in Hampshire where we were living. And we watched this film and it was basically saying effectively, you can create habitat for wildlife and grow food at the same time. They’re not mutually exclusive. And it was really going into depth about the sort of catastrophic effect of industrial agriculture, particularly in Australia, which is a fragile habitat and and the import of European and northern hemisphere techniques into that ancient, much drier brittler landscape, as Alan Savoury would say, was proving an absolute disaster. So they were way ahead of the curve on not only the sixth mass extinction and the effects of industrial agriculture, but they were also predicting peaking of oil prices and what that would do to the global economy and the global endless growth perspective and how impossible it is to fulfil that. So this kind of blew both of our minds. This was very early 90s and we also serendipitously met Robert Hart, who was the founder of Forest Gardening in Britain. He’d been to Kerala and seen those beautiful agro ecological systems, food forests, forest gardens, and thought, I can do this on a temperate scale.

And we met very early on the pioneering permaculture teacher Patrick Whitefield, who became our mentor and our author. And we worked very, very closely until his death. And we basically said, we’ve got to do this. This is a huge solution. We didn’t know anything about carbon sequestration at that time. We hadn’t really, the sort of pixel of climate chaos, hadn’t been energised in our internal screens. But somehow we had this sense of the vast possibility. And then the opportunity came that the Permaculture Association in Britain were looking for someone to take over their newsletter and we said, We’ll do it, but we need to take this to the general public. We don’t want to keep this just to a membership. We want to take this to the world. This is a global solution and we have got to get as many people interested in these ideas as possible. So we were incredibly young and idealistic, and we had that wonderful energy of, you know, we were early 30s. We had a couple of kids, but we just thought, wow, you know, we can do this. You know, ludicrous really, in our naivety of the scale of the job that we have still not finished 30 odd years later. But we’ve published over 100 books about permaculture and practical solutions and some visionary books about consciousness as well. And we’ve produced, we’re just about on 117 magazines. There were some years in the very early years where we didn’t quite hit the four. So the magazine started in September 1992, and we started publishing books in 1993.

Manda: And did you have a history in publishing? Because going from a newsletter to a magazine is a big jump.

Maddy: Yes

Manda: Okay, so you you knew the processes of that.

Maddy: Yeah. Well, kind of. I mean, I’d done a degree in practical criticism in English and American literature at University of East Anglia.

Manda: Does that teach you how to publish a magazine?

Maddy: It teaches you how to edit a piece for coherence and to see writing as a whole. And as you know, University of East Anglia is very focussed on creative writing and has all sorts of incredible literary alumni. So they did teach me how to write and how to critique.

Manda: Okay.

Maddy: So that was very useful. So I was an editor, a non-fiction editor, and Tim was a director of a small publishing company and we kind of left and threw that all up and quite madly started a publishing company to do the permaculture stuff.

Manda: Which was so visionary. This is what strikes me about what you’ve done. And yes, in our 30s we all have the wonderful naivety of youth and we think we can change the world. I think we still think we can change the world. We’ll look at that later. But the energy required to set up a publishing house is huge. And we didn’t have Amazon and Self-pub and all of the paraphernalia that we have now. It’s a relatively short time.

Maddy: Literally cut and paste.

Manda: Actually physically it was scissors and and Pritt sticks.

Maddy: Yep.

Manda: Wow. And when in the early days when you didn’t get the four magazines a year, was that because you were young parents and there was just too much else to do, or was it just lack of people writing you coherent stuff that was editable and worth putting out into the public?

Maddy: It was because we were very overstretched and we were producing books as well as the four issues of the magazine a year. But very quickly we realised that we absolutely had to hit those deadlines come what may.

Manda: Because your subscribers require it.

Maddy: And also all the teachers needed their courses advertising to the general public and and all the events needed to be publicised. So to grow the movement we absolutely had to deliver. And so we gradually found people to work with collaboratively that could help us produce the books and hit the deadlines and pay for it all.

Manda: Right. Yes. Because obviously, any magazine has to be self-financing. And it’s a big job to produce four editions a year. It’s huge. So let’s take a little bit of a step back. Several people on the podcast have tried to describe what permaculture is, and I don’t think we’ve really hit it yet. For people who for whom this is a new concept, can you tell us a little bit about the history of permaculture? Because obviously it did start in Australia and I think the fact that I’ve become aware of recently, that Australia was a farmed landscape. The indigenous peoples were farming it really quite specifically and in a way intensively, if we take intensive farming to mean a lot of human input. But it was a very different kind and style of farming than the Western invaders brought to it. But Bill Mollison and others started the permaculture movement there and then it spread around the world. So can you tell us a little bit about the history and about what for you permaculture actually is and does and what it’s evolved into being. Because in the beginning it was a horticulture or agriculture process and now permaculture of the spirit and the mind and the heart and of living seems to me as important as the growing. So evolve us into that.

Maddy: So very briefly, permaculture began as permanent agriculture, so very much about tree crops and agroecology, perennial cropping rather than annual harvests to secure and build soil. That was the fundamental principle, because the Australian landscape was so brittle and so fragile that you put arable onto it and like the dust bowl of the 30s, the soil just blows away and then you can’t grow anything. So that was the fundamental principle. And there was a lecturer, a university lecturer, Bill Mollison, and his master’s student David Holmgren, who wrote the first permaculture book in the 70s called Permaculture One. And it was literally perennial tree crops. But very quickly, Bill, because Bill had studied extensively not only with the First Nation people of Australia. He’d been a trapper and a fisherman and he’d spent months and months in the outback, and in the rainforests in Tasmania as well. He had a really intimate knowledge of ecosystems. He knew how to live and survive in the wilderness. And as a fisherman, he was very attuned to ecological change, because marine environments are so quick to alter and to degrade as we’ve seen now.

Manda: Was he a Sea fisherman or a river fisherman or both?

Maddy: Both

Manda: Right, Because rivers obviously change even faster than seas.

Maddy: Sure. But he worked as a commercial fisherman for a while. He had a very eclectic career. And he soon understood that perennial agriculture, permanent agriculture, which is where permaculture came from, was one aspect. But in order to communicate all that knowledge and wisdom and insight, he had to create principles and ethos. So permaculture is a design system fundamentally based on three ethics that are not exclusive to it: care of the earth, care of people and limits to growth or fair shares. And then a set of principles that Bill fleshed out in a book called Permaculture A Designers Manual in the early 80s, a huge tome, fabulous book. And that identified or decoded nature, in the sense that it looked at natural systems and said there are some fundamental universal principles, whatever the climate, whatever the country that makes nature work in a circular, sustainable way. And in order to create gardens and farms and communities in that self-sustaining, circular way, we need to adopt, understand, and then apply these principles. And these are simple things. This is stuff like we need to design biodiverse systems, monocultures are not resilient, common sense. But you know, we’re talking about the early 80s, So this was a whole set of thinking and principles that for people like me coming out of growing up in London and then university and then living in a city, were mind blowing. Because what they did for me was that they began to allow me to understand the landscapes around me and decode them, and see what was happening and see why they were degrading or why they had some, you know, sustainable properties.

Maddy: So looking at a broad leaf woodland and understanding that you’ve got circularity, you’ve got the Four Seasons; you’ve got the leaf fall that creates the leaf litter, which which then composts down, that then feeds the nutrients into the tree system. And of course the tree system is a highly sophisticated communication system that shares or doesn’t share nutrients between tree species and other plant and life forms. And then you’ve got all the niches between the floor and beneath the ground, all the way through the sort of ground cover to the shrub layers, to the trees themselves. So understanding that you’ve got a self nutrifying system that works on a seasonal basis, inhabiting every niche and taking advantage of sunlight, photosynthesis and edge. So you know the ecotones where the land meets the air, where the sun meets the glade, where the clearings allow different forms of plant life, which then support insect life, that support birds, that support mammals. So a whole mapping and decoding of how ecosystems work.

Maddy: That’s the sort of intelligent permaculture answer. The simpler one is that it’s about understanding how natural systems work and then applying those principles to our own life. And we can take it on many different levels. And one of our deepest aims was not to overcomplicate it, not to fill it with jargon and to make it as accessible as possible, so that permaculture can be taught, communicated and shared with people of all different cultures. So non-literary, non-western. I mean, actually, those people have a much deeper understanding of ecosystems than some kid from London anyway. It’s an arrogance in some ways, but it’s a good way of mapping it and having a model to share.

Manda: Brilliant.

Maddy: That’s what I’d say is useful about permaculture.

Manda: Oh, yes. Thank you. So clear and so inspiring. And what have you found over the years? So started in 1992 and now we’re 2023 we’re in a very different place. I think you and I, back in 92, even when I first met you in the early years of the millennium and Patrick was our teacher on a permaculture course that I did, and he is now the late Patrick. And he was so inspiring. And it felt then, it felt revolutionary. It felt like a return to a degree of indigeneity, you know, this is how it’s always been done but we can bring a 20th, 21st century spin to it. And thereby lift ourselves out of the chaos that particularly industrial farming is bringing. And we didn’t know then, soil science was in its infancy. You know, soil biology wasn’t a thing. And we didn’t understand really about the gut microbiome and about nutrient density in foods. All those things we have begun to learn about that have only layered on more incentive and urgency to why we should be doing this. And yet we are where we are. So you’ve been absolutely deep in this. You’ve been bringing 100 and nearly 120 editions worth of people who are right at the leading edge of this, who are putting it into practice, who are creating courses and events and workshops and come and work in our farm and you can learn this. How have you seen the trajectory of people’s understanding and of the spread and the deepening?

Maddy: So take ourselves back to the early 90s. We were very focussed on plants and gardening and understanding how forest gardens could work in northern hemisphere in temperate climates, and the kind of adjustments that you have to make between subtropical agroecology and temperate, cool, temperate permaculture. So that was the real focus at the time. And I got involved in the global Ecovillage movement when it was founded in Findhorn in around 1995, which was an incredible movement. A moment when people from Ecovillages and communities came together and said, We need to do this. This needs to be a movement that we share our knowledge and our understandings on a global scale. And that really got me looking at community. And at the time we were trying to set up the Sustainability Centre, that had been a naval base and was decommissioned and had become a sort of derelict military base that we had the opportunity to renovate and create as a charitable trust, that would hopefully demonstrate sustainability. So I got involved in this local community initiative as a founding trustee and really all my experience of ecovillages and community stuff and collaboration, was that we humans were actually a far bigger problem than ecology. You know, the ecosystems run. The web of life has a fundamental innate intelligence and wisdom and we humans have yet to grasp, most of us have really yet to grasp, perhaps.

Manda: I think we in the West, the western industrial rich, democratic, notionally haven’t grasped it. The indigenous people are an integral part of it, I would suggest.

Maddy: Oh, completely.

Manda: So it’s our culture that’s stepped away from it somehow and is trying to find a way back. Yes. Is that fair?

Maddy: We’ve broken the link. So the dominant paradigm is that we’re disconnected and that we’ve lost that wisdom and we need to get it back. And it occurred to me that in permaculture circles we had tremendously good ethics, but we didn’t know how to do people care. We’d go to events and my children, who were very little, wouldn’t have proper child care and would have to queue with the adults for their food. Children don’t wait for food when they’re hungry, they just become hysterical. And, you know, we didn’t have these basic personal skills even within this wonderful movement. So I got to be working with people like Looby Macnamara, who pioneered through her first book People and permaculture, a whole design system for personal, people care stuff. But also for looking at community design, but on the people centred level. And that then evolved with people like Starhawk and others into what was called social permaculture. So I would say that was a huge step forward, because permaculture was a blokes thing. There were no women teachers in the early 90s in the UK, they were all blokes and we were in the minority as women. So often I’d sit on a panel and I’d be the only female and everyone else was a man. And it was very binary as well.

Manda: And also very white, I’m imagining.

Maddy: Incredibly white, very binary and very masculine. So it was a real microcosm of patriarchal society and as abusive and damaging to the men involved as much as people like me. So I think that was one phase where we we started to really engage. And I trained as a psychotherapist in my 20s, so I was very focussed on counselling and psychotherapeutic techniques and group work. That was one of my backgrounds. So to bring that into the permaculture movement in a coherent way, for me felt really important. And of course the Ecovillage movement have enormous skills in conflict resolution and designing for people. So they were a huge asset and very helpful for my self-development. So that was the first sort of phase out of ecological systems. And then of course Bill was classically, although deeply engaged and respectful of First Nation people, he was very Australian white man. And so the spiritual aspect of permaculture or of connection, you know, let’s call it connection with the web of life, it horrified a lot of people. And if I ever published anything that was remotely about this other world, other dimension, you know, I would get stinking letters because people were very frightened about spirituality and it infecting something that was fundamentally scientifically based.

Maddy: So there was huge prejudice and a huge debate about spirituality. But, you know, spirituality is one of my founding principles and has been all my life. I was brought up as a Quaker. So all those ethics of peace and people care. I went to school with the Rowntree’s and the Cadbury’s, you know, So all of that stuff was utterly in my DNA growing up. My parents brought me up like that. So spirituality was not something that could be sort of pushed out of the way because it was an uneasy subject. You know, let’s not talk about God, sex and death. To me, we’ve got to talk about death because we’re living on a dying planet. Sex is very important if we’re going to survive. And it’s a big driver in a patriarchy particularly. And you know, God? Well, whatever God is. And obviously God is very culturally specific. But we’ve got to embrace these spiritual dimensions of permaculture. So the latest one, I would say, besides addressing the white dominance, the accusations of being colonial and culturally appropriating First Nation people and their values, is the fundamental principle of permaculture that is observation. But that is still from the I, the ego.

Manda: Right. Head based instead of heart based.

Maddy: And for me, the fundamental principle before we do anything is not the observation of the head, but the listening of the heart. And I think that’s the next dimension that permaculture needs to evolve into is this deep listening to the web of life.

Manda: And how is that going down now? Because we’ve moved on 30 years. You have spiritual aspects in the books that you publish and in the articles that you published. Do you still get stinking letters from people who want you to be a left brain agronomist?

Maddy: No.

Manda: Okay, good.

Maddy: No, I think they’ve given up with me, because you know this bloody woman, around for 30 years. I think some people still unsubscribe because it doesn’t work for them. But mainly now there is a far more holistic understanding. You can’t have your ecosystem design and keep people out. It’s like you can’t have science without some dimension of the effect of the observer now. We know this, you know, we’ve got quantum theory, so permaculture is not outside that either.

Manda: Okay. And I’m guessing you’ve got new generations of people for whom heart mind is not in any way antithetical. So I wanted to take a bit more of a linear look, but actually we’ve got here. Because it seems to me this is the crux of where we are now. It’s not that we use fossil fuels to power everything that we do, although that’s obviously a catastrophe. We’ve had the fossil fuel pulse, it needs to stop. It’s not even that we power everything that we do, although that also can’t continue. It’s that we haven’t figured out that core feature of what are we here for? What is, individually and collectively, what is humanity here to do? And that that is fundamentally a question of heart mind connecting to the web of life. And I’m wondering, as you’ve watched this evolve over time, as you’ve watched people become more relaxed with whatever spiritual articles you edit and produce. Or even, I’ve noticed there’s always – not always, but there’s often in the underlying narratives of the articles that you publish, somebody will make some reference to synchronicity. Or once we started on the path, we seemed to get help. I was just reading the one about revitalising black oats and and the whole rediscovering breeds and species of plant that we thought had gone, because monoculture’s arrived and GM and all the rest of it. And it’s in there. It’s an integral part. And yet we are where we are on the brink of the sixth mass extinction. And you know, the AI might switch us off before climate change gets us, but one way or the other, things are not looking good. How are you finding people or to what extent are you finding people are able to really connect with Heart-mind now? Because it seems to me that’s our big societal block. And yet I still think that if we can get a critical mass of people who are centred in Heart-mind, then we can move forward. Does that make sense as a question? It’s kind of a woolly question, but just where is that taking you?

Maddy: I think, first of all, there is an enormous shift from one generation to the next. So people of my generation, my parents were traumatised by their experience of the Second World War and had a very different relationship with their emotional inner life than even I did. And then the generations that have come after that are much more, I find particularly people of my daughter’s age in their 30s, far more emotionally intelligent and connected than people were of my generation. I’m 64, so I see a sort of psychological intelligence developing, but I feel that we are still very lost. And you said, what is our purpose as human beings on this planet at this time? I think we still lack a really deep clarity of that as a collective. Perhaps not the indigenous people at all, but perhaps, you know, the dominant Western model. And societies are still very lost. And I think young people face a huge amount of fear because they are not in denial about climate catastrophe and the unravelling. Some, of course, are asleep. But I think there’s a huge amount of consciousness and a huge amount of profound frustration and anger with the older generations who are not acting. And it’s not just, you know, Greta and her generation. It goes far beyond that.

Manda: As in the younger people than Greta? Or when you say far beyond, do you mean there’s more of them or?

Maddy: Millennials as well, people in their 30s who feel that my generation and beyond have not acted when we had the facts. And somehow it’s not fair. It’s not fair that that they’re being left with the scale of the problems when we could have done something. I think there is quite a lot of anger in in this and also a lack of, I think still collectively, a lack of clarity of why are we here. You know, what is our purpose as human beings?

Manda: Yeah. And it’s a very adolescent question. You know, Tyson Yunkaporta says this, and he’s hardly the first, that our culture kind of got blocked. We haven’t even reached adolescence, because adolescence is the writing bad poetry and then trying to find the meaning of life. And we’ve bounced off the hardness of that rite of passage and reverted back into the childhood see, want, take. You know, see sweeties, grab sweeties, eat sweeties and and there are no consequences because you’re a child. And I’m wondering, back in the 90s I thought, I think you thought, there was time to turn things around. That the climate apocalypse that we could kind of see on the horizon was a distant horizon. And provided we explained to people that the climate apocalypse was coming, everybody would change their behaviour. And now we know, neurophysiology has moved as fast as soil science and nutrient science and the biome, we know that that’s not a useful way to persuade people. That frightening people into action doesn’t work, and that what would have been better would be to have given them visions of a different future and the tools to make it happen. And 30 years have passed. We’ve burned over half the oil humanity has ever burned in those 30 years. And now we are where we are, and the climate apocalypse is basically here. And there are other apocalypses that we didn’t even think of. You know, the AI stuff was was not even a dream, except in the occasional science fiction model. And anyway, we had Asimov telling us that, you know, the laws of robotics were going to make it all fine. Do you still see a window within which there is the capacity to turn us away from the edge of the cliff? Or are we now trying to knit ourselves a parachute while in freefall?

Maddy: I’m going to give you a really, perhaps inadequate response and say, I really don’t know. Because I think about this at three in the morning a lot. I wake up and in those small hours, I wonder. My narrative for 30 years has been, yes, we can turn it around. That life has themost incredible capacity to bounce back. In all the work that I’ve done on a practical level, I took a completely destroyed field with no topsoil, no soil life, no birds flying over. And within ten years we turned it into a balanced, thriving forest garden. And by the end of leaving there and moving to North Devon, we had orchids growing in that field. In late 1990s, there was no topsoil, let alone flowers. So I know from my own work that when we humans become agents of change in a positive way on ecosystems, with other people within society, we can do incredible things. And we’ve had proof of that in all sorts of small events and larger events in the world. But I do feel now that the brinkmanship has gone beyond perhaps beyond the tipping point. And I’m not sure anymore. I know that we can still regenerate but I think there may have to be a period of not austerity, but but really profound climate chaos before the regenerative mechanisms can re-establish some sort of ecological balance. So I think we’re in for a tough time. Even if Rishi Sumac had a bolt of lightning to his head and suddenly realised that money wasn’t the deal and corruption wasn’t the deal, and actually what his children are telling him, because his children are saying it to him.

Manda: Oh, you think?

Maddy: Oh, they are. Yeah.

Manda: His actual children or his children’s generation?

Maddy: No, no, no. His actual daughter cares very deeply about climate. And even if they changed everything now, which would be extremely difficult, because we know that they’ve got embedded systems; that our political system is completely corrupt. I mean David Cameron wanted to kick start a solar revolution and instead within years of that, the feed in tariff and the solar economy was destroyed in the UK. And that was having a Prime Minister that was actually for it, hanging out in the Arctic and worrying about melting. I mean, I’m not saying David Cameron was a good guy because he made some critical errors.

Manda: Yeah, but, but also if he tried to do stuff, he would have lost his job sooner than he did.

Maddy: He was totally blocked. And my experience of going to the House of Commons and sitting on things like agroecology, you know, sitting in the audience when the Agroecology committee meets, is that the threshold of understanding of even the most basic stuff about agriculture and soil and carbon sequestration just is not there. There is not the intellectual capacity or expertise in the Houses of Parliament en masse to make informed, critical decisions. They’re not critical thinkers.

Manda: No. And our system would let critical thinkers we are. Isabel Harding wrote a really good book called Why We Elect the Wrong Politicians. And the System is designed to promote the kleptomaniac psychopaths. And that’s what we get people with remarkably short attention spans and whose whole focus is on pacifying the comments thread of the Daily Mail, basically and keeping Twitter happy. It’s not their fault because they are inadequate to the situation that they’ve been pushed into and they have to somehow paddle furiously to keep their head above water. But the water they’re trying to keep their head above is nothing to do with what’s happening around us in the sixth mass extinction. It’s a bizarre and very temporary social and cultural chaos. So accepting that I will get the book to you at some point, we’re still in editing. It takes a long time, this whole publishing process. But yeah, I think we need to abandon the existing political structure and create a parallel one that actually works and then we can move forward. However, what would be really interesting, and now I am blatantly doing research for the book, what does a permaculture politics look like? If you and I were to design and maybe you’ve already thought of this, bringing in all of the human design principles that you have amassed over the years to create a political structure that did elevate the best and the brightest, presumably not to be the ones making the decisions, but the ones to figure out the best way to implement the decisions that are made at more distributed levels. Have you a concept of what that would look like?

Maddy: I think we we have to look at design processes for that that are participatory. So so you know, when X are proposed citizens assemblies, they weren’t wrong because it was all about engaging the grassroots. When we engage people in their own communities, making their own decisions, then they’re more likely to own those decisions and work with respect for them. So I think you have to start at a grass roots level. You have to start by engaging people in the things that really matter to them, where they live, the facilities that that the children have, what they do about their health and food. And and it’s a it’s a very different world when we break things down to the simple levels. It’s not the world of this global economic growth model. It’s a world of local community resilience. And of course, the terrible fear for people about relocalization is that everyone’s going to become impoverished by it. But we know from all the testings of things like universal income. That when you pay, instead of paying people not to work, when you pay someone a basic income and then they can work as well, they they, they actually spend some of their time in service to their local community in some shape or form. Whatever floats their boat as on a volunteering basis. And then they work as well. Often people become more creative and and innovative and do interesting stuff. So I would say that those two principles would be like really important in a completely different system. I would also look at, um, you know, there’s been all sorts of energy experiments in Japan, for example, when they had an energy crisis, they, they had this whole system of, of conserving energy and they did it on all levels of society from in the, in, in industrial processes down to the home consumer.

Maddy: And they’d, they’d have times where it was really important not to use energy and then times where it was easier to use energy. And you know, on the TV, on the news channel, it would have the statistics of what energy was being used at the time and what people could do to preserve it. So for me, we would have to look at conservation of resources as a fundamental principles renationalise industries like water. I mean madness, the madness of of being run by an Australian company with American shareholders to actually provide drinking water to the general populace. It’s it’s insane. And as you pointed out on a recent podcast, there’s no difficulty in paying fines because the profits are so vast. So that’s all got to stop as a as a model for looking after basic survival services like clean water. It’s got to go. So So there would be there would be so many things Manda so many things that you could start you could take the best models from around the world. And, you know, I’ve loved Rob Hopkins What-if project because it hasn’t just been pie in the sky, Fluffy nice stuff that could happen in the future. It’s taken educational models, economic models, community models and extrapolated best practice from existing projects and then extrapolated them and said, What if we applied that to the world, not just the UK? And and it’s that kind of thinking where we’ve just we’ve got to go not, I mean, Keir Starmer yesterday when they signed the trade deal at the weekend said, you know, we’ve got to have industrial growth. And I’m thinking, Man, you’re an intelligent human being. It’s not possible.

Manda: No, no, no, no. Well, I think you’re giving him the benefit of rather a large doubt there. I keep trying to remind myself not to say bad political things about people. But yeah, the current political system is designed and built and maintained by people for whom endless economic growth is the only reality. And they don’t let you know Corbyn was in any Scandinavian country would have been considered centre right. But he was destroyed as a political force here because he wouldn’t have subscribed to endless political growth and all of the political ramifications around it. So we can assume that whatever political party is in power, whatever their kids are telling them, if somebody starts to step off the rails, they will be removed and somebody who isn’t going to step off the rails will be brought in. So we’ve got local community resilience. I’m really curious about the Japanese conservation of energy. Is that still a thing? Is that a model that could be taken up or did they get over their blip?

Maddy: No, but but you can research it. I think it was called Satsujin, but I’d have to look up the exact name, name of it. But it is a phenomena and it did happen and it was highly effective. And they saved vast amounts of energy without having sort of austerity and being cold or, you know, missing out because we waste just like we waste water in the most ghastly way. I mean, you know, water so precious. And it’s water. It’s sacred. So so the way we use it is, you know, culturally, utterly inappropriate and needs to be. Swarmed, but it’s the same with energy. But that’s.

Manda: Back to. We’ve got to decide what we’re here for, because if what we’re here for is is more and more.

Maddy: We’re here to become sacred human beings, aren’t we? And by sacred, I mean to make whole.

Manda: Yeah.

Maddy: You know, sacrifice.

Manda: So this is this has become my guiding question at the moment is, yes, I hear that. And also I’m aware that most indigenous peoples knew that. But I’m also aware that we cannot go back. We have to go forward, forward time runs literally until we find out the way to change that. We’re on a forward moving cycle and going back to Boudiccan times is not going to happen. And there was a phase about a year ago when becoming indigenous. Everybody just needs to become Indigenous. And you know, as a shamanic practitioner, that sounds great, but my core question becomes how do I go into the middle of Birmingham and talk to someone who’s got three kids under the age of ten, single mother living on the 10th floor of a high rise and say, okay, you just need to become indigenous, everything will be fine. It’s not a thing that’s not going to happen. So and I hear you. We’re here to become sacred beings, Connect to the web of life, ask What do you want of me? And be able to respond to the answer in real time.

Manda: That’s I think that’s what we’re here for. But it’s very glib and easy for me to say that and what I am striving for just now. What I think is the core question for humanity is how do we actually spread that and what does it look like? And this is this is essentially. Permaculture of the spirit. How do we help people? Because if we go into any inner city and sit down and go, okay, what really matters to you? Connecting to the web of life is unlikely to be in their top ten list. And yet if we spend a lot of time and energy sorting out their top ten list, the time and the likely fossil fuel energy is what’s going to take us over the edge. So we need to address people’s absolute underlying requirement to have a healthful and fulfilling life. That sense of being and belonging while extending their capacity to be heartfelt and spirit centred. And I have no idea how we do that and I am wide open to anyone who does anything striking you in the midst of all that.

Maddy: I mean, all I can speak of is, is the projects that I’ve seen for myself that that get people making and growing. So, so when people get access to small pieces of land for community gardens, when young people are taught how to germinate seeds and grow food, when people are allowed to are given the space to sit down around a fire and and share stories and drink cups of tea. You know, we’re not talking about great technological innovations and virtual reality headsets and millions of dollars of of development. We’re talking about the basic rights to air and and food and the the the the knowledge of of making growing and doing together. And that’s deep.

Manda: In. Right. And and fire, actually. Fire is really primal, isn’t it? It’s extraordinary.

Maddy: Well, I think when you sit around a fire with other human beings and you share stories, you do something, you connect back into your deepest DNA as a human being and something there is nurtured and fed. So so for me, I know it’s very simplistic and and it isn’t the solution to, you know, the cladding of high rise building crisis and the horrible lack of opportunity and unemployment and this awful industrial factory factory of of labour that’s used to feed the growth model. But if we can pull back from that and start to reintroduce and and really value these community based projects and particularly fire is one factor. Growing food because it is being in relationship to water and sunlight and soil. But these are elementally transformative things that are are, you know, humanity has always known about. But we’ve lost.

Manda: Yeah. And it reconnects us to the magic of life, doesn’t it? Just watch planting a bean and watching it grow never ceases to give me that sense of absolute magic.

Maddy: Exactly. And I grew up in North London with I mean, we had gardens, though, in those days, you know, not everything was built on. But I grew up in a very urban environment, but I was still and I remember planting that bean bean in a jam jar at primary school and it blowing my mind. And I don’t think everyone is going to have that experience. But I think a significant amount of the population, not only do we need food banks, but we need the the place to grow the food. Yeah. And we we need to look at cultures like Cuba who were forced to become urban gardeners because of their severance from Russian oil, from the Soviet Union oil system that was supporting that society at the time. And we need to look at what happened to them intellectually, intellectually, their universities in this tiny country became the absolute authority on agroecology, urban agriculture and organics. And they then exported that knowledge to Central and South America.

Manda: Right.

Maddy: And started, you know, sharing it with with, you know, other countries. And so I’ll go back to the idea that we have all of the solutions ecologically, possibly socially. It’s just that somehow we have to find the mechanism that wants us to harvest and share them. And I feel that the only way that we’ll do this is through utter collapse and crisis. I don’t think the mechanism of survival in our current societies has seems to have the consciousness or understanding that we’ve got to. Do it now and that it’s got to get worse before it will get better. And that’s grim. But it’s really grim. And I’m very sorry to be grim because I know my editorials are not grim, but this is actually the person this is where I am at the moment. And I’ve been thinking a lot. I worked with Joanna macy, who pioneered the work that reconnects when she was coming to this country quite a long time ago. And she always said, we have to sustain the gaze and we don’t know if we’re midwives giving birth to a new world or we’re actually nurses nursing a terminal patient. We don’t know. And in that moment, we have to hold the detachment and sustain the gaze. And that’s where where I am. It’s very it’s quite a Buddhist perspective, but it’s like if your absolute beloved was on her deathbed, would you get up and leave the room? Because it’s just so awful and you can’t watch it? No, you wouldn’t. You would be there till the end. And the Earth is our absolute beloved. And so we have to sustain the gaze. We can never give up whether we think that we are in the time of the great unravelling or this is the time of the great transformation, it’s irrelevant. We are here to sustain the gaze, to be in service and do our absolute best as a human being, whatever that means. And that is the meaning of life for me. And yeah, I’d love to become a whole and sacred human being, but actually my job at the moment is to sustain the gaze.

Manda: And that is being a whole and sacred human being. I would really strongly suggest that capacity to balance on the knife edge of the moment and give thanks in every moment for where we are and what we’re doing and throw ourselves fearlessly and wholeheartedly into being the best that we can be. I, I have yet to find a definition of being a whole and sacred human being that wasn’t that. Well, that’s.

Maddy: Lucky, because there’s nowhere else to be, is there?

Manda: No, exactly. There is nowhere else to be. That feels like a really balanced ending. But I have a question that’s really pushing up, which is how does your daughter’s generation hear that and where does it take them?

Maddy: It’s an extremely difficult conversation to have with people who are really entering the fullness of their adult life. To offer that level of. Complexity and restriction is quite wounding for them. And I think it’s a it’s a very difficult conversation. It’s a conversation that I can have far more easily with people who are not my own children.

Manda: But people of their generation.

Maddy: Yes. Yes.

Manda: Okay.

Maddy: Yes. Because it is it is a spiritual practice, this sustaining the gaze. Despite whatever. Yeah. And I think all we can do is is. Just. Try and be as good as we can. As agents of change and activists and see what we do as our form of activism. And it doesn’t necessarily have to be.

Manda: Gluing yourself to a bank.

Maddy: Yeah. Or throwing orange confetti in the Proms or you know, it’s not about that. It’s about what you bring into your daily life as a quality, whether you’re a film maker or a social worker or, you know, whatever you do professionally and whatever you do in your your private personal life on a day to day basis. And, you know, one of the things that helps me personally and helps a lot of people that I meet is doing the practical stuff, making the compost, sowing the seeds, being involved in community projects, volunteering, you know, being part of the better world that is possible rather than just sitting back and wanting it to happen, Right?

Manda: Theorising about it, but you.

Maddy: Know, actively getting out it. And you know, so that’s what I would say to any person half my age or younger is get involved, do stuff. Yeah. You know, use your hands and use your skills and develop your skills and learn stuff. And just be in service to it as a whole life project. Because, you know, I’ve got a dear, dear friend who’s 85 and she’s still doing seminars and online stuff and learning stuff. And she comes to a group that is held where I’m living now in the woods and is like the grandmother of our group, and she’s still deeply engaged in positive change of herself and supporting others to do so as an elder. And it’s an incredible thing to witness. And that’s the deal, isn’t it? For as long as we can draw air, we need to aspire to that.

Manda: Yes. Yeah. And I still want to believe because we don’t know if we’re midwives or we’re midwives in death at being a death doula. And I don’t see any reason why it can’t be both. This system has to die. The current system is is crumbling and it has to go. So we have to bemidwife ING the death of the current system. The question then for me is whether there is a gap before the phoenix arises from the ashes, so to speak, before because something will arise. It may not have humanity anywhere near it, but there will be something. It may take 10 million years for, you know, life forms more than amoeba to evolve in whatever we leave the planet as. But there will be something. And so, yeah, holding that uncertainty I think is is worth it. And I also am looking now quite hard being part of growing something new. But how can we help the dismantling of the existing system in ways that don’t cause it to crash such that ordinary people end up destitute? Yeah, that I think is quite an interesting question of what it’s kind of like a giant game of Jenga and which of these pegs can we pull out safely and and show that we’ve done so and show that life goes on in spite of the absence of whatever it is that we’ve just dismantled.

Manda: And I think the work that you’re doing of particularly we’re back if we look back to industrial agriculture is a catastrophe and it has to stop. That is something everybody could get on board with. Just just do not buy anything that is the product of industrial agriculture. Don’t buy anything that was grown as a monoculture because it’s not going to be good. And there are organic monocultures just as there are industrial monocultures. And that at the moment probably isn’t possible for anybody on a low income because industrial food is cheap food. But finding ways to make non-industrial food affordable becomes something active that we can do to help dismantle the existing system and promote something new. So I think I would I would like to promote the idea that not only do we sit where we are and do everything we can to be part of the solution, that we are also part of the the act of dismantling, and that that becomes part of our spiritual activism Also, because you’re right, it’s only a certain number of people can glue themselves to a bank or throw orange confetti at the Proms. And I have great respect for them.

Maddy: Oh, I’m not saying it’s not a good thing to do.

Manda: No, no, it’s but but I also was part of a conversation recently about spiritual activism with a lot of people our age going, I just couldn’t do that. And therefore I can’t be a spiritual activist. And I think that’s the bit that we need to get across, is if you’re one of the people who can throw orange confetti, this is back to Joanna Macy’s three pillars. The holding actions are essential there, things that bring to everybody’s awareness, the fact that the current system is broken and has to stop whatever you can do to stop the fracking or stop the water company chucking sewage into your local river, these are really essential things. And if you can do that, that’s great. But the changing the systems and the shifting consciousness are just the other two pillars of Joanna Macy’s. Three pillars of the great turning are also vital. And and we can be part of dismantling a broken system and helping anyone to grow. I didn’t mean this to become a manifesto of my stuff, but I just thought it was interesting to build on what you were what you were saying. Does that bring up anything for you?

Maddy: I would say simply that, yes, we we have to do whatever we can to build new systems and dismantle the old. And and there are times where we’d love to make grand gestures that were nationwide or European wide or global wide. But often all we can do is is do stuff within our local community. But that, you know, we know that there are tipping points and we know that that consciousness changes by by degrees and that you don’t have to have 50% of understanding or consensus to get an idea to tip over into the mainstream thinking it’s actually far, far less than you know, when I started, permaculture was completely unheard of in Britain. And and people would kind of look at us and think, you know, what are they doing? They’re just hippies. And and yet I’ve found myself in extraordinary circumstances in the last 20 odd years at Buckingham Palace and the Commonwealth Secretariat, who are really interested in permaculture. And you know, we call it the Surreal Permaculture Project because we like to see everything in black and white and them and us and we, we, we are sort of hardwired for division and separation. But the truth is there is no separation. And that, you know, extraordinary times. We have a king now who’s who privately has climate change meetings before large summits in his palaces. He can’t speak in the media or say anything because that contradicts his agreement constitutionally. But it doesn’t mean he’s not doing it right. And I’m not necessarily a royalist. I’m just someone who is an opportunist. And it’s like wherever we can go and dismantle, let’s do it. And there are people dismantling in places. And Joanna macy used to call them Shambhala Warriors. They are dismantling parts of the machine in unexpected places that we don’t necessarily think that they’re being dismantled.

Manda: That is a very good place to end on. Thank you. Good. So, so long live the people who are dismantling things in unexpected places. That’s grand and long live permaculture magazine because it’s been such an inspiration over the years. Well, thank you. So we will put links in the show notes for every way that they can contact you and your beautiful YouTube channel and all the other things that you do. Is there. Did you have anything else you wanted to say to people?

Maddy: I know that I said the unspeakable, that I did feel that we were in the great unravelling and I did talk about death, but I’d just like to say that I have given birth to two children in this life, and I have witnessed the passing of a number of people at the exact moment that they left their bodies. And I want to say to you that that experience was very similar, that the energy of life coming in and life leaving, leaving has the same extraordinary power. And so even though we might think we’re definitely well past the 11th hour, um, we really don’t know. And there is an incredible power in that mystery and in that process of life and death and that they’re not that far away. You know, we talk about linear time and deep time. Well, life and death are a similar energetic consciousness space, which is not linear. So who knows what’s going to happen.

Manda: Brilliant and beautiful. I love. We’re ending on a bit of uncertainty and the absolute magic of living and dying. That’s that’s truly fantastic. Maddie, thank you so much for everything that you are and do. It’s been such a pleasure and an honour to talk to you and thank you for coming on to the Accidental Gods podcast.

Maddy: I’m utterly privileged to be here. Thank you.

Manda: And that’s it for another week. Huge thanks to Maddy for all that she is and does. And thanks also to the permaculture magazine team who have created a coupon for us, actually for you, our listeners. If you type in permaculture Gods, all one word, all uppercase at the checkout as you subscribe to the digital or hardcopy versions of the magazine, you’ll get a free copy of Maddy’s book Fertile Edges, with your subscription. The link is in the show notes and the coupon permaculture Gods all one word, all uppercase, and it’s valid until 6th November. We talked about being part of the solution and about dismantling the old paradigm even as we build up the new one. And so this week, I really do encourage you to cancel any subscriptions you may have to the mainstream media. To the standard newspapers, whether they’re broadsheets or tabloids to the standard TV systems, anything and everything. That is designed to perpetuate the status quo and which feeds division. We have to stop. And instead you could use that money to subscribe to Permaculture magazine. It is a genuinely regenerative, huge hearted, strong hearted chronicle of good things that are happening now. It’s beautifully designed and the articles are genuinely inspiring. Every single time I pick up the magazine, there is always something that sparks a new idea, a new thought, a new way of seeing things and just joy that there are people in the world regenerating deserts, rediscovering Welsh black oats, building tiny houses out of things that I would never have imagined, creating a whole new water systems, food, forests, all of the things that we are going to need to know how to do when we don’t need the bizarre headlines that drag us back into the politics and the economics of a dying system.

Manda: So that’s your homework for this week. Cancel everything else. Use our coupon permaculture Gods and subscribe to Permaculture magazine. We will be back next week as ever with another conversation. In the meantime, huge thanks to Karasi for the music at the head and foot and for this week’s production. Thanks to Faith Tillery for sorting out our YouTube channel. Please do go and subscribe and for our Instagram, for the website and for all of the conversations that keep us moving forward. Thanks to Ann Thomas for the transcripts. And as ever, an enormous thanks to you for listening. If you know of anybody else who would like to be inspired by the ways the world is changing, then please do send them this link. And that’s it for now. See you next week. Thank you and goodbye.

You may also like these recent podcasts

Dancing the Path of the Inner Warrior with Diarmuid Lyng of Wild Irish Retreats

How can we find a way through the obfuscations and extractive values and downright lies of predatory capitalism. Through to authenticity, and integrity and finding language for how we can be who we really are, what our souls yearn to be. And that language is not always English.

Still In the Eye of the Storm: Finding Calm and Stable Roots with Dan McTiernan of Being EarthBound

As the only predictable thing is that things are impossible to predict now, how do we find a sense of grounded stability, a sense of safety, a sense of embodied connection to the Web of Life.

Sit with the River, Breathe Sacred Smoke, Love with the World: Building a Bioregional world with Joe Brewer

How can Bioregionalism supplant the nation state as the natural unit of civilisation? Joe Brewer is living, breathing and teaching the ways we can work together with each other and the natural flows of water and life.

Solstice Meditation 2025 – Sun Stands Still – by Manda Scott

Here is a meditation for the shortest night of the year – the time when the sun stands still.

It doesn’t have to be at the moment of the solstice, it’s the connection that counts, the marking of the day. And you don’t have to limit yourself to one pass through – please feel free to explore this more deeply than one single iteration.

STAY IN TOUCH

For a regular supply of ideas about humanity's next evolutionary step, insights into the thinking behind some of the podcasts, early updates on the guests we'll be having on the show - AND a free Water visualisation that will guide you through a deep immersion in water connection...sign up here.

(NB: This is a free newsletter - it's not joining up to the Membership! That's a nice, subtle pink button on the 'Join Us' page...)