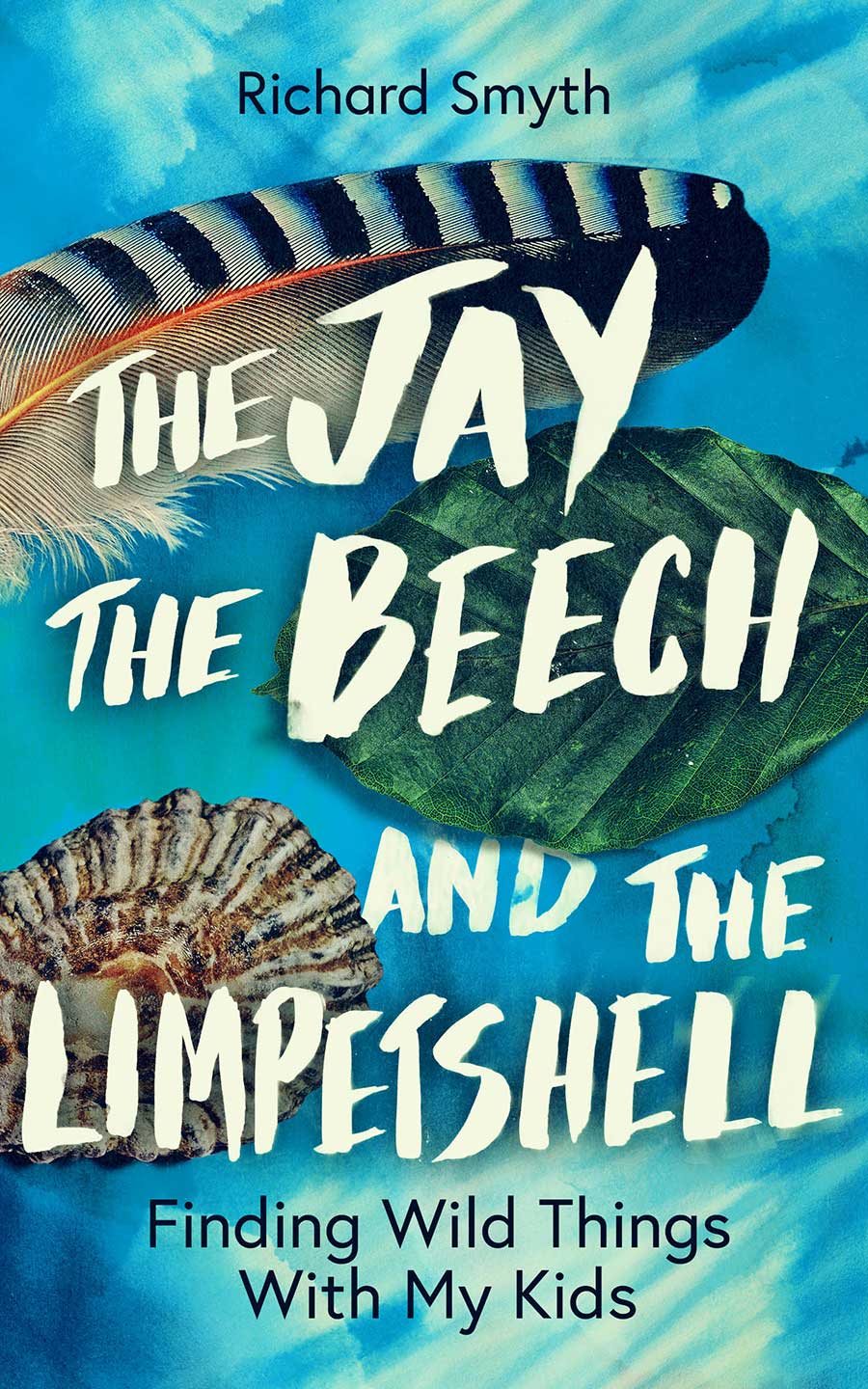

#238 The Jay, The Beech and The Limpetshell with author Richard Smyth

Our guest this week is Richard Smyth, author, crossword designer, cartoonist – and father of two young children.

Richard writes features, reviews and comment pieces for publications including The Guardian, The Times LiterarySupplement, The New Statesman, and New Scientist. His crosswords – both cryptic and quiz – appear regularly in New Scientist, History Today, and BBC Wildlife. He’s part of the team that sets questions for BBC Mastermind, and he’s a cartoonist: Private Eye, New Humanist and Claims magazines have all featured his work.

He’s the author of five non-fiction books of which the latest is The Jay, the Beech and the Limpetshell which is one of those captivating works that is both memoir and eulogy of a dying world. It brings together Richard’s passionate love of the natural world with his care for his two young children. It’s a captivating read that shuttles back and forth along the time lines, weaving Twitter comments from ‘Average Dad’ with items from the memoirs of old Victorian naturalists who tasted bird’s eggs and considerations of how we help the generations that come after us to fall in love with a world that is going to be so, so different from when we were young – however old you are now, whatever your memories.

So this is one or our more reflective, peaceful, contemplative podcasts, a paean to the worlds of our youth and a hope for the future. Enjoy!

In Conversation

Manda: Hey people, welcome to Accidental Gods. To the podcast where we believe that another world is still possible and that if we all work together, there is still time to lay the foundations for a future that we would be proud to leave to the generations that come after us. I’m Manda Scott, your host and fellow traveller on this journey into possibility. And for a short while, and I swear we won’t overdo this, I am also the author of the novel Any Human Power, and if you haven’t bought it and you want to support the podcast and all that we do, please do. I will leave a link in the show notes. And if you have bought it and you enjoyed it, five stars and a review on Amazon will definitely make an enormous difference to how we are ranked and how many people who don’t listen to the podcast stand a chance of finding out that we exist. So we would be enormously grateful if you could get around to that. And that apart, this week’s guest is a fellow writer who is also a crossword designer, which the geek in me got very excited about. Richard Smyth writes features, reviews and comment pieces for publications including The Guardian, The Times Literary Supplement, the New Statesman and New Scientist. His crosswords, both Cryptic and quiz, and I have to confess to not actually knowing the difference between these, appear regularly in the New Scientist, History Today, New Humanist, BBC Wildlife, History Revealed and The Blizzard, which I suspect has got nothing to do with World of Warcraft. There we go. He is part of the team that sets questions for BBC mastermind.

Manda: How cool is that? And he’s a cartoonist too. Private eye, New Humanist and Claims magazines have all featured his work. He is also the author of five non-fiction books, of which the latest is The Jay, The Beach and the Limpet Shell, which I read and loved. It’s one of those captivating, beautiful works that’s both a memoir and a eulogy of a dying world and a love letter to Richard’s children and the children of the world. It brings together his passionate love of the natural world around him, and his capacity to explore the histories of the naturalists who’ve gone before, some of whom were really quite bizarrely eccentric. So it shuttles back and forth along the timelines, weaving together Twitter comments from average dad from last year, with some of the more outlandish stuff from the memoirs of the old Victorian guys, mostly guys, who tasted birds eggs, amongst other things; and weaves with them considerations of how we can help the generations that come after us to fall in love with the world that is going to be so different from when we were young. However old you are now, it’s going to be different from when you were young. Whatever your memories, the world the new generations are growing into will be different. So this is one of our more reflective, contemplative podcasts, a paean to the worlds of our youth in the hope that we can create a future that works. So people of the podcast please welcome author, naturalist, crossword designer and father Richard Smyth.

Manda: Richard, welcome to the Accidental Gods podcast.

Richard: Thank you for having me.

Manda: How are you and where are you?

Richard: I’m very well, thank you. I’m as tired as any parent of two small children can be, but otherwise well. And I’m in the small town of Saltaire, just outside Bradford in West Yorkshire.

Manda: Beautiful. Is that where you were when you wrote the book that we’re going to talk about?

Richard: Yeah, a great deal of it is set in and around Saltaire and Shipley and Airedale in West Yorkshire.

Manda: Right. Gorgeous. So you have written a book which your publishers very kindly sent me and it’s gorgeous and I think well worth exploring the themes within it. So could you read us the opening paragraph? Because that’ll give us a setting and we can move on from there.

Richard: My daughter’s pockets are empty. She’s three and she doesn’t want to put things in her pockets. What use are they there? The things we find, shells, sticks, feathers, pebbles, leaves, fragments of ice, she wants to carry them. Handle them, taste them, break them. Or she wants daddy or mummy took after them. There’s the long cone of a pine tree from Northumberland in the pocket of our car’s offside front door. There’s a daisy wilting in an espresso cup of water on the kitchen windowsill. There’s a small stack of sticks in the hall. Have you got a dog? The postman asks. My own coat pockets fill up with snail shells and alder cones. She doesn’t know a lot about any of these things. She’s three, give her a break. But I know she’ll learn.

Manda: Beautiful. And then you go on to mention your son as well. Who knows that crows and blackbirds and ducks go quack and frogs go Ribbit! And he’s watched a lot of David Attenborough. And he can snap his jaws like a crocodile and nearly say elephant. How old are they both now?

Richard: So they’re now five and five. But they were three and two when I started writing the book.

Manda: So actually, this book was written and published quite fast, in the realm of publishing cycles.

Richard: Uh, fairly quickly, yeah. And it jumps around a lot in time. So I do have a note at the start of it where I explain that it’s not told in chronological order, and that my daughter is at one point three and at one point four, and my son is at one point a baby. And then suddenly, as happens to babies, no longer a baby. So I hope that’s not too disorienting.

Manda: Yeah. No. And it wasn’t. And it had that beautiful immediacy that I think, I’ve never been a parent but I’ve watched it happen to my friends, and it’s a great lesson in living in the present moment, because it’s almost impossible to live anywhere else.

Richard: Absolutely.

Manda: And we kind of lose that as we go along. So tell us a little bit about your pre parenthood life that led you to be someone who could write The Jay, The Beach and the Limpet Shell.

Richard: Well, it’s interesting because I grew up, I was a nature mad child myself, but not because I grew up in the countryside or in the woods. And I wasn’t a sort of feral rural child, I grew up in the fairly comfortable suburbs in West Yorkshire. And I was turned on to wildlife mainly well, by David Attenborough, by Terry Nutkins on TV, by the bird books. And my granddad was a little bit of a birder, so he had a few books lying around. So I think through those sort of things that let you experience nature at one removed. And then, of course, there’s the immediate nature that you find even in the comfortable Wakefield suburbs, you know, the woodlice, the occasional hedgehog, the blue tits on the feeder. And that was my thing as a kid. And I found I drifted away from that, as kids often do when they hit the teenage years, and it stops being cool. And then I drifted back to it when I started my freelance career. And to be honest, at the start, when I was panicking about what I was going to write about I realised I still had this store really, of knowledge that I’d absorbed as a seven year old. And I started writing about birds again, and I started thinking about birds again. And the more I thought about them and watched them and studied them, I’ve always said that nature is very good for thinking with. And that’s how this book works really. It takes various jumping off points and goes in all kinds of different directions. But it all starts with looking, just as I did when I was seven, the bees on the fuchsia and the ants on the path.

Manda: Thank you. And it’s a beautiful follow on to last week’s conversation with Deborah Benham, who’s a biomimicry educator and has done a lot of work with Jon Young on deep nature Connection. And as far as I can tell, you haven’t done the Jon Young work or any shamanic work or any anything like that, but you’re still deeply connected to the living world around you, even in exactly as you said, a suburb of Bradford. I am curious as to you start your job and you start panicking about what you can write, and most of us don’t have jobs that lead us to panic about what we’re going to write about. Tell us a little bit about why finding something to write about became what you needed to do.

Richard: Well, I’ve always written since I was a kid. And I never really struggled for what to write.

Manda: Was it your profession though? Did you have to write professionally?

Richard: It has been for the last, gosh, since 2008 I’ve been a full time freelance writer. And so at that point you stop just having to think about what to write, you have to think about what you want to write that other people will want to read. Which is the main difference between an amateur and a professional writer. So like I said, I’ve been writing since I was little, but most of that’s been fiction. And when you’re writing fiction, you don’t necessarily have to worry about who’s going to read it. When you’re trying to pay the rent and then pay a mortgage, you have to sell your writing. And nature stepped in at that point. And obviously, the question then is, why do people want to read about nature? And the answer is kind of what you mentioned, that interconnection that we all have. And that’s what the book’s about, really. I mean, it’s only partly a book about parenthood. I mean, I do go on a bit about being a dad, but more than that, I think it’s about being a kid. And that has been central to my experience of being a parent, because I remember it so vividly. And that’s the universal element; not everyone’s a parent, but everyone was once a kid. And that’s something I really wanted to talk about.

Manda: And the way the world is changing, because that becomes through the book as well, really deeply. That what you experience as a child and what your children are experiencing is not the same. And and we know the trajectory of that. However, before we go into that, because it is beautiful and magical and I want to go in more deeply. I’m still curious about someone who I’m guessing had another day job and then one day decided, no, I don’t want to, I just want to be a freelance writer. Which is an incredibly courageous, you know, we’re using this in the Yes Minister version of courageous, way to do things. Because the rest of us, you know, we have the day job and we run the day job in parallel with the writing job until we’re not getting any sleep, but at least the writing job is paying. And then we gradually stop the day job. Or at least that’s my experience. And you just went cold turkey and went, okay, now I’m going to write and pay the mortgage and raise my kids?

Richard: Well, I should say, if it sounds like I’m making any claims to to great courage. When I went freelance, I didn’t have kids and I didn’t have a mortgage. I was living on my own, I had rent to pay. But yeah, I had a boring job in legal publishing. I waited a long time for a redundancy option to come up, and when it did, I took it. And yeah, and then there we were, off and running. So yeah, I started out with very little to go on in terms of experience or connections or anything like that.

Manda: But you had been in publishing.

Richard: Yes. Kind of. I mean, if I wanted to carry on being a freelancer in this very specific world of law and European case law and so on, I would have been all right. But I didn’t and that was why I left. I went freelancer with the purpose of writing what I wanted. And that’s the greatest sort of achievement you can get as a freelancer, in my opinion. It took me years to get there, and I’m more or less there now.

Manda: And what made you choose non-fiction over fiction? A lot of people who listen to this podcast are quite curious about the writing process, I think. So I’m just going down that road for a little bit and then we’ll broaden out to what you’ve actually written. But most people who decide they’re going to ‘be a writer’, head down the genre fiction role.

Richard: Well, I write both, still. I consider fiction my first love, probably. And when I was starting out, well, probably for the first half of my career so far, non-fiction was much more like a day job. I mean, it was something I enjoyed and I’ve never written anything I didn’t want to write, in terms of books, but at the same time I didn’t have complete freedom and you know, I wasn’t just thinking of something I wanted to write about and then writing it. So fiction has always been there chugging alongside, not really paying its way in any way, as fiction tends to. But I’ve always done them side by side. And now in particular with the last 2 or 3 books, I feel like it’s the non-fiction I want to write, and consider the two parts of my writing fairly equal partners. Not financially, because fiction is always going to be the junior contributor in that regard, but in terms of sort of how personal it is, I suppose.

Manda: Okay. Because you have collections of short stories, if I understand correctly.

Richard: No, I’ve written a lot of short stories, but they’ve not yet been collected. But I’ve published two novels, one a very long time ago now and one in 2020.

Manda: Right. Lockdown.

Richard: Yeah.

Manda: Okay. We will link to those in the show notes and perhaps talk a bit about them later. The other thing I just wanted to explore, because I find it completely fascinating, before we dive into The Jay, The Beach and The Limpet Shell; you set crosswords, am I right?

Richard: Yes I do. That’s been the mainstay of my career, to be honest with you. One of my first freelance jobs was setting the crossword for History Today magazine, the venerable institution.

Manda: Does that mean you had to have historical clues all the way through?

Richard: Yeah. And I’m still doing after 16 years.

Manda: Goodness.

Richard: Yeah, it’s a very strange way to make a living. So I now set for New Scientist magazine…

Manda: With all scientific clues? Does that mean you have to read New Scientist a lot and then develop clues based on the recent papers?

Richard: Some of them are scientific, some are cryptic, and they can be a bit sciencey. I do one for BBC Wildlife magazine, which is wildlife themed. I do one for New Humanist magazine, which is cryptic. So it’s a very strange one of those freelance things, you know, you never know what’s going to come along or what might end up being a plank of your career that you never thought would be.

Manda: I can feel a whole podcast on this, but we won’t do the whole podcast on this. I’m completely hopeless at crosswords, but I watched Faith doing them and periodically she’ll go, you know, what do you think about this? And I’ll say, I think somebody else was setting the crossword today in the Guardian or the Independent, because it’s just so completely off the wall from what they normally ask. How long does it take to set a crossword?

Richard: Cryptic ones take longer for me. So I’d say I’d spend in total, it probably takes about a day for me to set a cryptic.

Manda: Not necessarily cryptic, let’s just say BBC wildlife or a historical one.

Richard: They take me a few hours, I would say.

Manda: Just talk me through the process of do you create a grid? Is there AI that helps now that creates a grid and certain words in it, and then you just have to think of the clues?

Richard: This is the glimpse behind the curtain here, I’m not sure I should be, I’ll be defrocked for sharing trade secrets.

Manda: Oh really? Oh well, don’t share anything that isn’t obvious.

Richard: Oh no, no. In the old days you had to very carefully set out your grid and you had to think a lot about layout. Since I’ve been doing it, which is, like I said, for over 20 years, there’s software. I mean, it’s not AI it’s just fairly basic software that selects grids for you and can put in the words for you if you want, but tells you what fits the spaces you need to fill and so on. The clueing is the art, obviously. But I would say that.

Manda: Well, you would. But also if you’re doing history and wildlife and New Scientist, you have to actually know your stuff. Because nothing will annoy historians, I was about to use bad words there, or scientists or naturalists more than inaccurate clues. So you’ve got to not only know what you think is true, you’ve got to know what they think is true. And with my limited experience in the historical world, people will claw each other’s eyes out over, you know, where the Roman legions landed. And if you do one place you’re going to so badly annoy the people who believe in the other one, that they’ll probably just swamp your editor with so many bad letters.

Richard: It’s true. I’ve been quite lucky so far. The one thing that does get people het up in BBC Wildlife magazine is plurals. Some people get very cross if you use an s plural for most animals and birds, which I tend to do.

Manda: What, like blackbird and blackbirds?

Richard: Yeah, well I think it comes from a sort of game background. So if people talk about pheasants, the plural of pheasant is pheasant.

Manda: Oh I see, yes. Dear Lord.

Richard: That kind of thing. Well deer obviously nobody says deers.

Manda: Yes. Mouses.

Richard: Yeah. Yeah. Exactly. That’s the one thing that really gets people going. But mostly otherwise, other than that, I’ve got away with it so far.

Manda: Could I put in a vote? The thing that would piss me off enormously is, is the verb that conjugates with extinction. Because when I grew up it was to become extinct and now it’s to go extinct. And even the New Scientist says to go extinct. And it drives me absolutely batshit. I hate it.

Richard: Wouldn’t you say, to become extinct.

Manda: A species becomes extinct. Yeah. Just point that out to the editor next time.

Richard: Okay, I’ll bear that in mind for future. Yeah.

Manda: Thank you. Well, that’s made my podcasting day absolutely perfect. All right, let’s get back to your book. Because we could carry on talking about crosswords and probably lose about half of our listeners. So, listeners, we’re heading back into a very beautiful book called The Jay, the Beach and the Limpet Shell, which Richard has written. So let’s start with the Jay. And one of the things that I highlighted was Gavin Maxwell, because I remember reading Ring of Bright Water when I was a kid and being completely absorbed and Tarka and Midge, I realise Tarka was different, but but they all kind of swirled together in this magical sense that people and non-human species could live with a heart connection, I think was the thing that really struck me. And it seems to me that what you’re writing about is introducing that level of heart connection to your children. So they may be collecting an infinite number of bits of stick so that your postman thinks you’ve got a dog, but they’re doing it, I would say, and this is what I want to check as a way of establishing that they belong in this world. That the world isn’t just suburban wherever with four walls and the television, it’s the world of mud and mess and fragments and and later on in the book, you look at an owl pellet. And I know that Faith’s grandkids, they can spend an entire afternoon dissecting an owl pellet. Or somebody found recently a kestrel pellet, and it was full of bits of beetles and that’s how we knew it was a kestrel pellet. And there’s that awe and wonder that kids have. So take us a little bit, I’m not sure how we approach this, but take us through perhaps your experience of coming to grips with the book and the memories. Do you keep a diary or do you just remember stuff because you’re so sleep deprived it’s all happening in the present moment anyway.

Richard: In all of my writing, I have a sort of simple faith in the sort of back office of my brain to produce things when I need them. And the analogy I’ve used before is composting, and I don’t know if you compost or not, but we have one out the back, and I’m always struck by the miracle that happens. You know, you throw in this diverse lot of rubbish out of your kitchen waste, and then a few months later you check the bottom and how? How has this happened?

Manda: Yes! You’ve got this black gold.

Richard: Yeah. And that’s how I describe my writing process, such as it is. I put a lot of stuff in there, let it compost down, let it rot down, and then see what comes out, which is not a very precise way of doing things, but that tends to be how I write. So no I don’t take notes or anything like that as a rule.

Manda: You must take notes from some of the historical characters. Because there’s so much about fascinating Victorian historians. There was the one who ate things, and now I can’t remember who it was and what they ate. Can you remember that bit?

Richard: Charles Waterton. Who was a man I feel I have a slightly special connection to because he was from Wakefield, which is where I’m from. But he was back in the early 19th century. He was a classic, eccentric, but also one of the first great conservationists. He had a very unusual, at the time, feeling for birds, particularly, and wanted to protect them. His estate at Walton was a bird reserve, back when there was no such thing as bird reserves. But he was also a very strange man and very argumentative man, which is one of the great things about researching him, is you go through all these obscure beefs he had in the pages of natural history journals with other these obscure natural history subjects. But the reason I talk about him in the book is because he was, more than anyone else I can think of, a hands on naturalist. He climbed trees until he was in his 80s. He was just seized by that urge, which is quite a childish urge I guess, just a human urge to to grab and touch and feel things with his with his hands. And not just with his hands, as you say, one of the things he says in one of his books is, it’s a myth that you can scare away birds from their nest just by approaching it. As long as you’re calm and gentle, you won’t do that. And then he says, you can even pick up the eggs and put them in your mouth and then put them back, which is wonderful, I think.

Manda: Yes. And they don’t run away.

Richard: Yeah, exactly. They’ll come back after a bit. And he just embodies the sense of that urge to grab and to grasp. It’s always been a watchword for me because I’m aware that as I say, I grew up with nature often, often at a remove. He warned back in the early 1800s of naturalists who spend more time in books than in bogs. It wasn’t really popular natural history in his time, so he’s talking about academics, you know, theoreticians. But at the same time he was championing then this idea of practical engagement with nature, which is a big theme of the book.

Manda: And he was a contemporary of Scott of the Antarctic who was the father of Peter Scott. Is that right? Or they just came together in the book?

Richard: No. Well, an understandable mistake, because a lot of things are thrown together in this book, like in compost. And I do jump from one to the other. So we’re almost exactly 100 years before Scott.

Manda: Okay. Sorry.

Richard: No, no, that’s quite okay.

Manda: But I was really struck by Scott, in his final letter to his wife Kathleen, famously urged her to make their son interested in natural history. ‘If you can, it is better than games’ which presumably was in the era when everybody got sent away to public school, if you had the money. The kind of people who were able to go off on expeditions to the Arctic because they weren’t trying to feed 17 kids and survive long enough, and obviously it worked.

Richard: Yeah, absolutely. So Peter Scott was one of the great conservationists of the 20th century. I mean, Scott was a great polymath, I suppose would be the word. I mean, he wasn’t a genius himself, he wasn’t particularly academically gifted. But one thing that you get if you read about his expeditions is the sense of being interested in everything. And one of his closest friends was Edward Wilson, who died with him at the pole. And he was another character I write about in the book, he was a great ornithologist who really fostered Scott’s interest. But everybody on the polar expeditions had this wide ranging interest, wide ranging enthusiasm and wide ranging passion, really, for want of a better word, for collecting. This is another thing that interests me about our engagement with nature.

Manda: They had a tendency to kill them and pin them on boards.

Richard: They absolutely did, yeah. And some of that, you know, you can justify through science and the need to study. Some of it is just this childish, whether that’s good childish or bad childish, I don’t know; a childish urge to seize and to take. I mean, I’ve said before, people often say, oh, children are born naturalists. They’re natural naturalists. I would say that’s true, but they are not born conservationists, because they’re much more like rapacious Victorian collectors than anything else. You know, they want to go out and take things. They want to seize things. They want to pull up the flowers, they want to see the eggs in the nest. And that’s one of the things I write about, is how difficult it is to tread the line between those two positions. Because now, less than ever, we can’t go out and find the eggs and trample the flowers. We have to tread so carefully and ever more carefully as the world becomes much more fragile. And that’s a hard thing, because when I was a kid, that was all I wanted, was to physically engage with nature. Grab it, take it, collect it, look at it closely, keep it in a box. And we simply can’t do that anymore. It’s a little bit heartbreaking.

Manda: It is. And that takes me in two directions. I’m remembering, my mother ran a rehabilitation centre for birds of prey from our relatively rural home. And every year when I was a teenager, the BBC decided it was fun to run Kes in the nesting season. And so there was a local, what used to be called a new town, which was basically a concrete box, and all the kids would decide they were going to get a Kes, and they’d go out and raid the local nests, and then they’d have them for the summer holidays. And come the end of the summer holidays, their mothers would tell them to take it back. And of course, you can’t. And there would be this huge influx of kestrels. And regularly every summer we had this huge box in the kitchen, and the baby kestrels and the baby owls would swap over at dawn and dusk, and we’d have to try and find out ways to get them back out there. And I was growing up working out how we could release these things and how we could train them to hunt. And realising that if somebody didn’t train them… In the end, we had a pair of adult kestrels and provided we supplied the food they were racing around, feeding 23 young kestrels going completely bonkers. But provided they had a food supply, they could do that. And then they taught them to hunt, much, much more effectively than we could. And similarly with the owls.

Manda: So I’m wondering do indigenous kids want to own things like that? Or is it some strange colonial aspect of our being? Because reading through the book and particularly reading all these old historical characters, they were all public school boys of a particular imperial mindset that wanted to own the rest of the world and thought that that’s what you did. And then they wanted to hold them on leads. And they were great naturalists, but they didn’t leave us a world where we conserved very much. And I’m wondering two things. First of all, do you think this is actually natural human instinct or is it natural for our culture? And then second, now that your kids are a little bit older, are they able to understand that there aren’t enough hedgehogs to bring one home. And that kestrels are dying out and that sort of thing.

Richard: And so the second question, yes, certainly. I mean, kids, not just through to me and my wife, but through school, through pre-school. I think it’s part of the conversation now. It’s part of our understanding of natural history that we look after the planet, and we’ve always been told to do this or that to look after the planet by my daughter. And so they certainly have a sense of that.

Manda: What sort of things? What does she want you to do? Like turning off lights and recycling?

Richard: Well, recycling yeah. If she sees litter, we agree that that’s bad for the planet. Bad for our planet is the phrase. And that kind of thing. So it’s embedded from a very young age now. Whether it’s our culture I honestly don’t know. I don’t have enough experience of indigenous practices to say. My hunch would be that I doubt it. I mean, I suspect it’s more likely to be the other way around. I think we all have an urge to take what we like, and that has informed our culture in the past more than it should have, and in the present, for that matter.

Manda: But I’ve never read a story of say, First peoples of the Americas or any of the indigenous peoples; they had hunting dogs, they had horses. I’ve never heard of any of them having a pet anything else. Maybe they there were taboos against it or they just didn’t need to, because they were in a world where they were in free exchange with them anyway, and they could go and see them.

Richard: Yeah, I think that’s a big part of it. The element of novelty, for want of a better word. I mean, I used to read a lot of Gerald Durrell, all those kinds of books about animal collection.

Manda: My Family and other animals, I remember.

Richard: Exactly. All that stuff. And a recurring theme is word goes around the local people that this British guy is in town and will pay money for vermin or, you know, whatever creatures are running around the place. And they all turn up with bags of this or that animal, saying what does what on earth does he want this for? But then they exchange it for money or whatever.

Manda: Is that because he was being paid to keep them down? Because I don’t remember that bit.

Richard: Not specific to Gerald Durrell. I can’t remember where it comes up, but in all of these stories, the word goes out that this guy is trying to collect animals to study, for zoos and things, and then they bring anything they find to see what they can get for it or just to see if he wants it.

Manda: Right. Yes.

Richard: Novelty is I think central to it. It’s certainly where I was interested because, you know, it was so rare for me to get close to a living thing, I could probably remember each individual instance it was so rare. Which wouldn’t be the case, of course, if I’d grown up somewhere slightly less distant from the Wild, so to speak.

Manda: Yes, in an indigenous lifestyle. Gosh, so many different ways we could go with this. So one of the pages I have marked in your book, we’ll go here first, because then I want to take it in a slightly different direction. And you write: in spring last year, the Twitter user Average Dad, who I will have to follow because that’s obviously an interesting thread, posted a line from his kid that set me on edge for months. In fact, I’m still on edge and the line was: dad, isn’t it weird that the word chicken can mean an animal or a type of food? His kid had asked. My kid, remarked Average Dad, on the verge of making a horrific realisation. And at that point you didn’t think your daughter was there yet. But then there is a complicated place.

Manda: So this feels like almost a rite of passage in parenthood and a childhood life for children of our culture. And again, indigenous kids grow up knowing where everything they eat comes from. And we famously, whether it’s true or not, have kids who don’t know that milk comes from cows. And clearly, for Average Dad, don’t know that chicken comes from chickens. And so I’m wondering, is your daughter there yet? And how the conversation went and where it went after. Where did it take her?

Richard: To be honest I think both the kids at least have the general idea of what happens. And it was all a bit less traumatic than I expected. I think to start with, certainly for my son, it seemed more ridiculous to him than upsetting. What? We eat what? It just seemed an extraordinary thing for us to do. But I think kids can just roll over some things without a bump, and that seems to be one, which took me by surprise. There was a brief thing about I don’t want to eat a chicken, but I think it was just a sort of dissonance more than anything.

Manda: And do they know that milk comes from cows?

Richard: Oh yeah. They’re pretty clued up on on all that sort of thing. We haven’t gone into the process exactly yet, but they know that the meat that we eat sometimes is from animals.

Manda: And do they grow food otherwise? Somebody I listened to on a podcast the other day said every school should have a garden producing some of the food for the school. And getting kids back to their hands in the soil and watching potatoes grow and watching beans grown. Because it’s amazingly magic, that a little bean it makes beans.

Richard: Potatoes in particular. Yeah.

Manda: Well, I have to say, I’m completely fascinated by beans always. It’s just so exciting. And you get so many from one bean. It’s really wonderful. But go on. You were saying about potatoes.

Richard: Potatoes are just magical when you dig them up. How did these clean round things happen? It’s incredible. And so we try and do that in our little backyard, growing things in pots. And school does seem to be very good. They’ve also been to forest school, so they’re quite familiar with all this sort of stuff and getting their hands extremely dirty and faces and all the rest of them.

Manda: Yeah. Which is good for their biome, I gather.

Richard: Yes, hopefully. Yeah. And yeah, the meat thing, I mean, it’s all of a piece with the knowledge that they’re getting of nature. And this is one of the big things in the book for me, because when I first started talking about this book, I’d always say it’s about bringing up kids to love nature. That was my sort of one sentence sell. Then I realised, well, firstly, as I’ve already said, it’s not really about bringing up kids, it’s about being a kid. Secondly, it’s really not about loving nature because love is far too simple a word, if love can never be said to be a simple word. It’s far too simple a word for our relationship with nature. And this is where I feel a little distant from a lot of discussion of of nature. Because it’s horrible, nature is a very hard place, a very hard world.

Manda: In what way? Expand on that a bit.

Richard: It’s violent. It’s nasty, brutish and sharp. I take a dim view of it, quite frankly. You know, you talk about, well, predation is the obvious one. And that’s where my chapter on meat eating comes from. You know, we’ve got peregrines. We’re very lucky to have peregrines visit our local mill chimney. And I’ve explained peregrines eat pigeons.

Manda: And then Genevieve says, why? I thought that was lovely. Why? Why do they eat pigeons?

Richard: Yeah, absolutely. Why? That’s their favourite question. And then we found a pellet, which is where the chapter begins. And you have to talk about, well, yes, this used to be a shrew or a vole or a beetle and it got eaten. And that’s just how it works. That’s the system, that’s how nature works. That’s how it operates. So I take Darwin’s position that it’s a cruel, wasteful, blundering way of making things. It’s a horrible way of making beautiful things.

Manda: How would you do it differently?

Richard: Well, I wouldn’t. I don’t think anyone can set out to design a functioning ecosystem from scratch, but the fact is that I’m looking right now at where we have our blue tit nest over the over the road. Blue tits nest there every year, and blue tits lay about ten eggs per clutch. So a stable population of blue tits means that eight out of every ten dies, either it fails to hatch or it doesn’t fledge, or it fledges and dies before it can breed.

Manda: Or it gets eaten by the local cats.

Richard: Exactly. Or the peregrine. Some people have gone to extraordinary lengths to sort of get into the maths of this. There’s an academic I quote in the book who has studied the suffering of cod, who thinks of the suffering of cod? But he calculates these vast spawnings that cod do, you know, millions of eggs going out into the sea. A tiny proportion even hatch. A tiny proportion of those make it anywhere. And that’s life. That’s how it’s made. No one could dispute that it’s monstrously wasteful apart from anything else.

Manda: But it’s monstrously wasteful if you didn’t have a food chain. But most of those cod are feeding various sizes of things on an ascending food chain, which is actually quite efficient if you look at it that way.

Richard: Well, yeah, if your goal is to just create more stuff. Sure. But, it means that the lives of individual creatures are expendable. So yeah, in terms of supplying the whole system with material, it’s very good. In terms of ensuring that individual creatures are, for want of a better word, happy, whatever happiness means to a cod, it’s not very good. And so my relationship with nature is I’m fascinated by it. It’s often beautiful, it’s complex, which is what I want from things. It’s incredibly, infinitely complex. It’s complicated, but it’s also hard and it asks a lot of questions that we often struggle to find answers to. And so a big part of bringing up my kids to be comfortable with nature is bringing them up to be comfortable with those hard facts and to engage with the complexity.

Manda: And the ambiguities inherent within.

Richard: Exactly. Ambiguities is a good word. Yeah.

Manda: I was listening to someone who lives, I think, near the Baltic Sea, who in their childhood and in their grandfather’s childhood, you could almost walk across the cod and now there are basically none. And in their life the herring were plentiful and now there are basically none, because there are factory ships sucking them up in order to turn them into fish meal to feed to mink, to make coats for rich Russians. And that strikes me as the single most salient fact about the complexity of the natural world is that we are capable of breaking pretty much every part of it. Because we have no idea, probably of the complexities of which the cod was an inherent part. Again, Deborah Benham last week said that it’s just been discovered that the redwoods that are on the Californian coast, she did her PhD on the sea otters and the kelp forests off the California coast. The kelp forests are reliant on particular runoff from the redwood forests. So there’s a whole land sea ecosystem, and there’s probably a feedback loop that kicks back up to the redwood forests, about which we know absolutely nothing, but it’ll still be there. And the amount that we don’t know is probably orders of orders of magnitude more than we do know.

Richard: Absolutely.

Manda: And yet we’re happily sucking all the fish out of the Baltic Sea to feed mink, to make coats, because someone can make money out of it, which is terrifying. And in terms of the numbers, you write: all of our remaining reptiles, whales and dolphins, 57% of our amphibians, 43% of our freshwater fish, 37% of our land mammals and seals, 35% of our bumblebees, and 33% of our butterflies are depleted or at risk. And the thing to remember is these were only the species losses, the UK extinctions. We still need to talk about decline. So you have to imagine as you walk, a falling silent of farmland, birds, turtledoves, skylarks. Of commoner birds like starlings and tree sparrows. Of flying insects like bees and beetles. And you have to imagine a dying away of hedgerows, grasses and wildflowers. Between the mid 1930s and the mid 1980s, about 97% of the UK’s wildflower meadows were lost. And that’s just heartbreaking. I kind of know these things, but I didn’t have the numbers in my head.

Richard: It’s extraordinary, isn’t it?

Manda: Do you have a sense that your children’s generation, obviously they’re not getting their heads around these numbers, but I worry that shifting baseline syndrome, which was originally described with fish stocks in the sea, that it applies to everything, means that it won’t impact at the visceral level that it impacts us. I remember when every time you went for a drive in a country road, there was a dead hedgehog because cars were relatively new and hedgehogs were plentiful. And now I can’t remember the last time I saw a squished hedgehog and it’s not because people are avoiding the hedgehogs, it’s because they aren’t there.

Richard: Yeah, it’s a harrowing thing to go through. It’s a slow motion crash, isn’t it?

Manda: I think it’s quite fast actually, but yes.

Richard: Well, on an ecological scale it’s incredibly fast. It’s an eyeblink. But on a human scale, it’s.

Manda: Yes, it’s over a lifetime.

Richard: Yeah it’s over half a lifetime. It’s heartbreaking to think of how it could be when my kids are my age, because I can look at how it was when my grandparents were my age. The figures are there, those are the figures you were just reading out. I can see exactly what’s going to happen if it continues like this. Yeah. Those numbers are going to keep going down.

Manda: And at some point we’re going to hit the tipping points where everything just collapses. And it seems to me that we’re probably quite close. How do we get to the point, you said you were really interested as a kid, and then you went to secondary school and it stopped being cool. Have you got a sense of ways that we could help the younger generations, the one for whom it is still fun, how we can get past the it stopped being cool phase so that it stays something that’s cool all the way through, or is that just not going to happen?

Richard: I think if you’re trying to breed the concept of cool out of teenagers, I think you’ve got an uphill task.

Manda: I was never a cool teenager, so it never struck me, so I don’t really get it.

Richard: Well, no, me neither. Exactly. When people do what I do, as a lot of people do, you know, drift back to their to their geeky interests. They often say, oh, I realised that being cool isn’t important. That’s never true. What they mean is, I realised it was too late for me to ever hope to be cool so I’ll just do what I want, which is much more accurate. The main thing is to get those hooks in there early and then hope they come back. I mean, obviously it’s great some kids will stick with it through the teenage years, will never drift away, will never feel that they shouldn’t be doing it or never feel dweeby or feel they wouldn’t rather be hanging out with their mates or whatever. But if you accept some inevitability that some teenagers will want to not go birdwatching, then yeah, the main thing is to make sure you get them when they’re young and then it’ll stay with them. It does stay with you. I mean, even when I was a teenager I’d always be distracted walking along by a bird flitting by or whatever it might be. So it’s always in there as long as someone, some group of people, some community, some society has done the job of getting it in there in the first place.

Richard: I write in the book about forests and woods, because we spent a lot of time in the woods, particularly during lockdown. And now both my kids have done forest schools. One of the important things is it’s great to learn about the trees and the bugs and the birds and all that, but the most important thing about being in the woods when you’re a kid is learning how to be in the woods. And I don’t mean learning how to survive in the woods, built shelters or whatever, just how to be there without thinking, shit, I’m in a wood! You know, without feeling like you shouldn’t be there, without feeling alien. One of the teachers at Forest School I was speaking to not long since said they can tell some kids know how to be in the woods, and some kids don’t. It’s not about what they know, it’s not about what they can articulate, they just now have to be there. They know how to be happy in a wood. And that’s one of the most valuable things I think you can give a kid.

Manda: Or an adult.

Richard: And that means you don’t have to know about what tree’s what and what bird’s what. I mean, it’s great if you do, but you don’t have to. That’s not what it’s about, really. Fundamentally, it’s much more about the learning to be in those places.

Manda: Yes. And that’s one of the Jon Young things, is go back to the same sit spot, your secret sit spot, day after day after day after day for the full cycle of the seasons and beyond. And just sit there. And exactly that. You don’t need to know the Latin name of all the trees, but you need to get to know the ones that you know and see how they change with the seasons, and see what comes and sits in them, and develop that empathy with them. Do you think from the Forest School experience, that the kids who don’t know how to be in a wood can learn?

Richard: Absolutely. I absolutely think they can, yeah. At the bottom level I think it’s just familiarity. And the understanding that it’s allowed, it’s okay, it’s good in fact. It’s not weird. It’s not somewhere that you go and then go where you’re meant to be afterwards. It is where you’re meant to be and where you can be. I don’t think it’s that complicated. And well, speaking with no knowledge of childhood development apart from my own experience, I think it’s fairly easily done. You know, chuck your kids in a wood and see what happens. That’s my parenting advice.

Manda: But you have to take their mobile phones away first, I would think, because otherwise it’s just you lean up against a tree and you’re scrolling whatever it is that Snapchat, TikTok.

Richard: Well mine aren’t at that point yet, they’re currently free of that.

Manda: Well done. And there’s this beautiful bit where, Gary, who is leading you smiles and leads the way up past the allotment to a gate in the fence. And then for the first time in my life, I’m in a wood. What the hell? Let’s call it a forest. That I planted. That is, I planted part of it. I planted one tree, I think I was nine. Now the tree is 34 years old and towers overhead. Tell us about that. Because I just thought, oh, I planted a forest. Well, actually I planted one tree in a forest, but that’s good and it’s there and it’s big.

Richard: Yeah, my class planted a forest. I never really thought about it for a long time. When I was in primary school, we had a big playing field, again right in the middle of the suburbs, it wasn’t anywhere dramatically rural, but the top part of our playing field, we all went out and planted a tree one day. And yeah, when I left school, it was still a little sapling. But then not long since I thought I’d go back and have a look. And yeah, there’s a whole wood there. It’s incredible. Yeah.

Manda: What kind of tree did you plant?

Richard: I’m not entirely sure which was mine, and I don’t remember which sort of tree it was from when I was nine. I think it was a cherry, a wild cherry, but I could be wrong.

Manda: Okay. Yeah. And they grow quite fast, actually.

Richard: But one of those trees was definitely mine. And yeah, that was so nice to see. It made me feel extremely old, but it was a nice thing to be a part of, to go back and see. And the kids at the school now hang out there. Again, it doesn’t matter if they’re looking for Beatles or and birds or if they’re just sitting in the shade or just chasing each other around the trees.

Manda: Yeah. They’re experiencing what it is to be in a proper forest.

Speaker3: Exactly.

Manda: And in the book, you said that this kind of education was huge a century ago. A US popular science magazine from the 1890s reported that in many places in Europe, school grounds are very much better managed than this country. School authorities appreciate the training, which results from pruning, budding and grafting trees, ploughing, hoeing and fertilising Land, hiving bees and raising silkworms. Really? did we raise silkworms in the UK? But still, yes and surely that needs to come back. That sense of how to manage trees in a way that is useful. We seem to be getting a lot of conversations here about whether to let hedges grow up, or whether to lay them, and the number of people who actually knows how to lay a hedge properly is vanishingly small.

Richard: Absolutely. I mean, we need the skills we need. From a practical perspective, it’s very hard to say what we need the kids to learn in terms of practically doing stuff. I think that’s secondary as far as I’m concerned, to learning just the very basics of being practical and being in woods.

Manda: And then at the end, your epilogue: I’m writing this on the hottest day the UK has ever known. The news has just come through that the temperature at London Heathrow has topped 40°C. Which, I have to say, I never thought I would see in the UK in my lifetime, and I’m pretty sure you didn’t think so either. You’re not that much younger than I am, actually you were born the year I left school, but I left quite young. Do you have any sense of cultural change amongst the younger people. Your kids are way too young to create cultural change in and of themselves, but in terms of the way that they are appreciating the world or their slightly older teenage peers are appreciating the world? It seems to me we’re going to get change and we need change. It’s the younger generations. I don’t want to push it on them, and I would like to be able to hold the space, but that the impetus for ‘we have to do things differently’ is unlikely to come from the people who are in the last quarter of their lives, and more likely to come from the people who are in the first half. How does that land with you?

Richard: Well, I mean, it’s our only hope, isn’t it, really. As you say, I don’t know enough about that generation and that generation as a whole. I know the kids who are visible and doing great stuff that you read about in the papers and on TV. That doesn’t represent the whole. So I don’t know what the youth culture is going to be. You know, as I said, kids, even in my day at school, environmentalism was drilled into you even then.

Manda: And look where it’s got us.

Richard: That took hold, Yeah, exactly. So it’s not enough to leave school parroting buzzwords. It does take more than that. Whether we’ve got that, whether the next generation will have that, I honestly don’t know. I hope they do. And as you say, it’s a terrible burden to leave them with. It’s not a great legacy for our generation, or the generation before us.

Manda: No. The only thing that I can think of is that it is also an astonishing opportunity to be alive at the time when total transformation is going to happen one way or another, and you can perhaps shape the way that it goes forward. And I think your last paragraph in the book, at least before the the rather lovely further reading and the notes, is: it’s all change, everything will change. It’s hard to see how it will all pan out. It’s hard to see how anyone will make it all alright. Whatever alright looks like. I don’t know and can hardly imagine what part my children will play in it all. For me, for now, it’s enough to know that they’ll be in it somewhere, out there learning, exploring and taking it in their hands.

Manda: And bringing it home and making nests of twigs and shells and everything. Have you read bits of the book to them, or is it just too old for them yet?

Richard: No, it’s a bit much for them yet. I’ve shown them the bit at the start where it’s for them. And the note where I talk about how old they are. And they know there’s a book, that daddy wrote a book and they’re in it. But that’s it for now.

Manda: Is it the only one of the books that you’ve written that have your kids in?

Richard: Yeah, yeah, yeah, it very much came out of being a being a parent.

Manda: Sleepless nights.

Richard: Yeah. I thought long and hard about whether to put them in, you know, use their names, things like that, because we’re quite protective of their privacy. But one of the reasons I wanted to write it was because it will be there forever. You know, that book’s there now, I’ve expressed myself on so many things that I hope they will be interested in, you never know do you. About how I feel about them, how I feel about their place in the world and all these things. And that’ll be nice for them to have.

Manda: So it’s like the old Victorian explorers who wrote everything down and left it to their kids. You’ve got this as part of a legacy, I guess.

Richard: Yeah, exactly. This is my my collection that I’m passing on.

Manda: And where next? What are you writing now?

Richard: Um, I’m working on many things at once, as usual. But I’m currently developing a proposal for a book about the environment and far right politics. Something I’ve written a little bit about before.

Manda: Brave.

Richard: But it’s something that fascinates me. So yeah, I’ve been sort of trudging through some quite unsavoury history recently. But yeah, that’s my focus at the moment.

Manda: Interesting. And do you think that if we were able to shape a vision of a future, no, let me rephrase this. I’m thinking about what little I know of far right politics, which is mostly Steve Bannon and his white supremacist, patriarchal Christian theocracy, which doesn’t have much environmental stuff in it. And the one thing that makes me quite sanguine about the fact that his 10,000 year Reich cannot happen is that he’s going to hit biophysical limits that he doesn’t acknowledge exists. So,the ecosystem will fall apart before he gets his 10,000 year Reich, which is just fine. However, there are people on the far right who have very, to me, strange ideas of herding everybody into cities and then rewilding the whole of everything that’s left. And we all eat ultra processed foods and presumably die quite young of horrible chronic diseases. Can you, with the research you’ve done so far, and this is obviously a whole different podcast, and we’ll come back to it at some point, but envisage a way in which we and they could find common aims? Or is it that their need for white patriarchal supremacy trumps everything else? I use that verb deliberately.

Richard: Yeah. I mean, it’s very difficult to talk about finding common ground with white supremacists. But one of the main things in my thinking about this is that you often see, when people talk about this kind of thing, it’s always that the far right is sort of parasitising or hijacking environmentalism. And that does in some cases happen. Sometimes it’s opportunism, but there is something much deeper. Some of the things that draw us towards environmentalism, conservationism, are the same things that draw people towards far right politics and extreme politics. That’s my starting point, and that’s what interests me. That’s something we can’t shy away from, that’s something we need to understand and that’s why I went to write this book. So Common Ground.

Manda: And what are those things? What is the common ground?

Richard: Well, attachment to the land, whatever the land means. Something that I’m quite interested in is this whole idea of how we belong to the land or the land belongs to us. There’s all kinds of ideas about belonging and nativism. So many different things that I think needs to be unpicked if we’re going to construct a good way forward.

Manda: That’ll be interesting. Okay. Get your publicist to send me a copy long before it comes out, because that would be a really exciting thing to unpack. But you haven’t written it yet, so we’ve got plenty of time.

Richard: Yeah. Watch this space. Thanks.

Manda: So I really look forward to reading the next book. I have loved reading The Jay, the Beach and the Limpet Shell. Is there anything that you would like to read for people as we end?

Richard: Yeah. I’ll read you a short passage from one of the many great minds that I write about in this book. This one in particular is Bill Watterson, whose name people might know; he was the creator of Calvin and Hobbes, one of the great cultural works of our time. And I’m just going to read the dialogue from one of my favourite strips from 1995. And it’s when Hobbes the Tiger comes across Calvin the boy crouching by a creek. Hobbes: what are you doing? Calvin: looking for frogs. Hobbes: how come? Calvin: I must obey the inscrutable exhortations of my soul. Hobbes: Ah but of course. Calvin: my mandate also includes weird books.

Manda: I love it. He was such a genius guy.

Richard: He was.

Manda: Yeah. I love that he puts into the mouths of children such extraordinarily deep and thoughtful things, and the inscrutable exhortations of my soul is just… I want that on a T-shirt somewhere. Brilliant. Richard, it’s a beautiful book, it’s beautifully written. Your children are very lucky to have such an amazing wordsmith plus a dad who makes crosswords.

Richard: Thank you. That’s very kind.

Manda: It’s extremely cool. So I look forward to talking to you again when your next book is out. And in the meantime, thank you for this one. And thank you for coming on to the Accidental Gods podcast.

Richard: Thanks so much for having me. Thank you.

Manda: And there we go. That’s it for another week. I made Richard 15 minutes late for the school run. Richard, I am so sorry. But I’m also grateful for those last 15 minutes of conversation because that felt like a really interesting avenue to be going down, and I am really looking forward to reading that book. But in the meantime The Jay, The Beach and the Limpet Shell is just beautiful. I hope we gave you a flavour of Richard’s writing because it’s so fluent. He brings together so many diverse ideas and weaves them into a coherent narrative that gives shape to the ordinary world around us and makes it magical. That brings it alive in ways that the gaze of children brings things alive. And if we didn’t end up with magical ideas of how to transform the world, we did have magical ideas of how to see the magic that’s there in front of us, and how to bring it alive for the generations that are here now. So if you’re looking for something beautiful and in a way soul restoring to read, then head off and buy Richard’s book. There are links in the show notes.

Manda: And that’s it for this week. We’ll be back next week with another conversation. And in the meantime, huge thanks to Caro C for the music at the head and Foot. To Alan lowells of Airtight Studios for the production. To Anne Thomas for the transcripts. To Faith Tilleray for the work behind the scenes and for all the conversations that keep us moving forwards. And as ever, an enormous thanks to you for listening. If you know of anybody else who wants to explore who we have been and who we could be, then please do send them this link. And that’s it for now. See you next week. Thank you and goodbye.

You may also like these recent podcasts

Call to Adventure! Crafting an Integral Altruism with Jonas Søvik

What is Integral Altruism and how could it crowd-source the answers to our meta crisis?

It’s a while since I learned about ‘reverse mentoring’: a young person mentoring someone of an older generation. The idea really took hold, so when a mutual friend connected Jonas Søvik and me, I knew I’d found someone from whom I could learn a huge amount about life, ideas, thoughts and how the world feels in circles I would otherwise never reach.

Honouring Fear as Your Mentor: Thoughts from the Edge with Manda Scott

Manda dives deep into the nature of fear, what it is and how we might find our own resources, resilience and capacity to work with the parts that catch our attention. Given this, it is recommended that you listen at a time and place where you can give it full attention.

Co-ordiNations vs the Network State: Greenland and the Schism in Global Vision with Dr Andrea Leiter

What is a Network State and how does the concept matter in relation to the Trump administration’s attempts to take Greenland – and their ‘peace’ proposals in Gaza and Ukraine?

Tracking the Wild Things, Inside and Out – with Jon Young of Living Connection 1st

How can we step into our birthright as fully conscious nodes in the Web of Life, offering the astonishing creativity of humanity in service to life? Our guest this week helps people do just this…

STAY IN TOUCH

For a regular supply of ideas about humanity's next evolutionary step, insights into the thinking behind some of the podcasts, early updates on the guests we'll be having on the show - AND a free Water visualisation that will guide you through a deep immersion in water connection...sign up here.

(NB: This is a free newsletter - it's not joining up to the Membership! That's a nice, subtle pink button on the 'Join Us' page...)