#235 The Story is in our Bones: Rewilding Ourselves with author and activist Osprey Orielle Lake

Once in a while, a book comes along that changes how we see the world, that re-sets something fundamental in who we are and our capacity to engage with the Web of Life. Braided Sweetgrass by Robin Wall Kimmerer was one of these: at once poetically beautiful, spiritually inspiring and deeply thought-provoking.

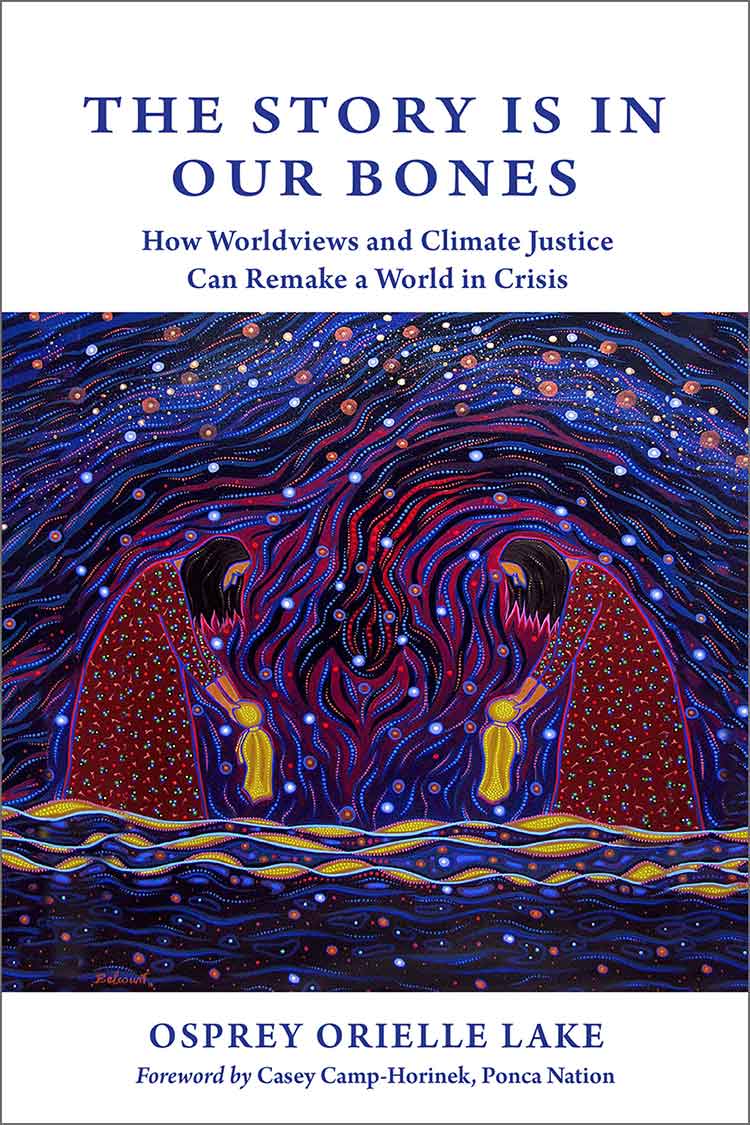

And now Osprey Orielle Lake has written The Story is in our Bones: How Worldview and Climate Justice can Remake a World in Crisis. This is a genuinely beautiful book on every level: full of living mythology, opening doors to how the bones of our language make the world around us, offering other perspective, other ways of being, living stories of where we came from and who we are and who we could be. It’s deeply honouring of Indigenous wisdom from around the world, and of the struggle of all those who suffer most and have done least to unleash the poly crisis that is so obviously impacting our world.

The author is an extraordinary person, founder and executive director of the Women’s Earth and Climate Action Network (WECAN) which was created to accelerate a global women’s movement for the protection and defense of the Earth’s diverse ecosystems and communities. She sits on the executive committee for the Global Alliance for the Rights of Nature whose goal is to ‘transform our human relationship with our planet’ and on the steering committee for the Fossil Fuel Non-Proliferation Treaty, which is modelled on the Nuclear non-proliferation treaties of the last millennium, and seeks to manage a global transition to safe, renewable and affordable energy for all. In short, she works internationally with grassroots, BIPOC and Indigenous leaders, policymakers, and diverse coalitions to build climate justice, resilient communities, and a just transition to a decentralized, democratized clean-energy future.

This is one of those conversations that dived deep into the heart of what really matters – how we bring ourselves to a place of genuine connection with the Web of Life – in time – and in ways that will create the more beautiful world our hearts know is possible. We could have talked for hours, and I have no doubt we’ll come back again, but in the meantime, please enjoy the many layers of being and belonging that Osprey brings to all her work.

In Conversation

Manda: Hey people, welcome to Accidental Gods. To the podcast where we believe that another world is still possible and that together we can create a future that we would be proud to leave to the generations that come after us. I’m Manda Scott, your host and fellow traveller in this journey into possibility. And if you listened last week, you’ll know that I write books and read books. Many, many, many books, most of them for pleasure and some of them are really mind blowing. And once in a while a book comes along that changes how we see the world, that resets something fundamental in who we are and our capacity to engage with the web of life. Braiding Sweetgrass by Robin Wall Kimmerer was one of these; at once poetically beautiful, spiritually inspiring, and deeply thought provoking. And now there’s another. Osprey Orielle Lake has written The Story in Our Bones; How Worldview and Climate Justice Can Remake a World in Crisis. This is a genuinely beautiful book on every level. It’s full of living mythology, opening doors to how the bones of our language make the world around us, and how we could remake it differently. It offers other perspectives, other ways of being, living stories of where we came from and who we are and who we could be. It’s deeply honouring of indigenous wisdom from all around the world, and of the struggles and voices and understanding of all of those who suffer most and have done least to unleash the poly crisis that is so obviously impacting our world. Osprey is an extraordinary individual. She’s the founder and executive director of the Women’s Earth and Climate Action Network, which shortens to WECAN and which was created to accelerate a global women’s movement for the protection and defence of the Earth’s diverse ecosystems and communities.

Manda: She sits on the executive committee for the Global Alliance for the Rights of Nature, whose goal is to transform our human relationship with our planet. And she’s on the steering committee for the Fossil Fuel Non-Proliferation treaty, which is modelled on the nuclear non-proliferation treaties of the last millennium and seeks to manage a global transition to safe, renewable and affordable energy for everybody. In short, she works tirelessly and internationally with grassroots Bipoc and indigenous people, with leaders, with policy makers, and with the most diverse coalitions to build climate justice, resilient communities and a just transition to a decentralised, democratised, clean energy future in which we address all of the systemic problems of the poly crisis. This is one of those conversations that dived deep into the heart of what really matters. Of how we bring ourselves to a place of genuine connection with the web of life in time, and in ways that will create the more beautiful world that our hearts know is possible. We could have talked for hours, Osprey and I. And I have no doubt we’ll come back again, but in the meantime, please enjoy the many layers of being and belonging that Osprey brings to all of her work. So people of the podcast please welcome Osprey Orielle Lake, author of The Story is In Our Bones; How Worldview and Climate Justice Can Remake a World in Crisis.

Manda: Osprey, welcome to the Accidental Gods podcast. How are you and where are you and what time is it in your part of the world?

Osprey: Well, thank you so much for having me on your podcast. I am in California on Coast Miwok lands, which is in Northern California, and I’m just very happy to have this time with you today.

Manda: Thank you. You have written an absolutely glorious book. I genuinely think it’s going to be the Braiding Sweetgrass of this decade. It’s beautifully written. It’s very to the point of what we need at this point in the meta crisis. I’m going to read a little bit from the start of it. I might be tempted to read other bits later, we’ll see how we go. I mean, fundamentally, I would like to just read the book, but that would take longer than the podcast and then I wouldn’t get time to ask you questions, so I’ll read this bit and then we’ll see where we get to:

Manda: ‘Along with many people globally, I have committed my life’s work to addressing the dire circumstances we face and to envisioning and building the healthy and just world we know is possible. This moment calls for deep systemic change, entailing a metamorphic shift in worldview. Literally, how we understand the world and our relationship and responsibility to the web of life and each other. Worldview is a vast topic that is as crucial and marvellous as it is mammoth, with dramatic differences depending on culture, environment, ancestry, mythology, epistemology, and so much more. Thus the chapters ahead, though they cover a range of geographies, are just one offering to a collective conversation that is sprouting in varied fields of knowledge and around the world in diverse contexts’. And I read that and my heart sang, because you’re so clearly on the page that we need to be on, and thinking so deeply about the ways that we can all bring the collective agency of humanity, the creativity of humanity, to creating the changes that we need. In starting to talk about this, I wonder if we could go back to when you were three years old and the story of the Thunder Arrow. Because it seems to me that’s probably not the starting point, I suspect you were already on this path, but it felt reading it a really visceral, profound movement into a different way of being. Over to you.

Osprey: Well, thank you for reading that introductory piece. I think many of us are so concerned about what academics are calling a poly crisis, where the systems that we’re in from our cultures and society and I should say dominant culture, not everyone, but the dominant culture, is unravelling and terribly violent and destructive. And so I think many of us are collecting around, you know, what is the world that we’re birthing? As one world is dying, hopefully we can hospice that in a graceful way. And then how do we bring forward the healthy and equitable world that we are so passionately committed to? And so, yes, this is really a very key component of my life’s journey. And I don’t think I’m alone in that. But how do we go about addressing these issues? And that’s really what I’m trying to get at in my book, is the worldviews and the upstream Conversations. And I mention this because as executive director and founder of the Women’s Earth and Climate Action Network at WECAN, you know, we’re dealing every day with very practical issues of stopping fossil fuel companies or going to the UN climate talks or starting food security programs or reforestation. You know, helping the Amazon and Indigenous leaders there to stop deforestation. So there’s all these fires that are going on that have to be put out. At the same time, I’m really aware that we have to go upstream to address root causes of these problems and address the worldviews that birthed them, because if we don’t unpack that, we will just repeat. And so that’s the moment I think we’re in.

Manda: Yes. So can you tell us about when you were three and the Thunder Arrows? Because it felt to me that was what moved you on to a path that, frankly, is not yet normal within our dominant culture. And yet you’re on it. Tell us that little story just because I think it’s beautiful and then let’s see where it takes us.

Osprey: Sure. So I open the book with a whole journey about talking about worldviews. And one thing that impacted me in my youth is my family was living in Germany for several years when I was a toddler, and at three, we landed on the East Coast and drove in a Volkswagen Bug across the United States. And at some point we were in the southwest, and I spoke to my mother about it later, so I’m not exactly sure where we were. And by the time I figured out to ask her, we all didn’t exactly remember, but it was I think in the pueblos somewhere in New Mexico. And anyhow, indigenous people there very kindly do at times open up their ceremonial dances to tourists who are outsiders. The deeper knowledge, of course, is kept secret as it should be and protected. But some of it is made public, you know, joyous community celebrations. And this particular event that we went to was during a rain dance ceremony. And part of the dance involved one of the dancers in full regalia bending on one knee, and he shot an arrow from his bow up into the sky and up it went, up it went. And I saw it go all the way up into the stars.

Osprey: Which also relates to a lot of the other information in the first part of the book. Anyway, the arrow came back and landed in my belly button in my stomach and I thought it was very normal. I was very impressed and delighted and thrilled of having this experience. And the dancing and the songs and all of it was just so very different than anything I’d experienced. And of course, these are tidbit memories because I was three, but I distinctly remember these these components I’m sharing with you. And I shared that with my parents, you know, excited. And they, no judgement, they were concerned. It didn’t fit into their concepts of reality. And they quickly explained to me in so many terms that this is a simulation, that it wasn’t real, that this was to bring rain. That the arrow was shot into the clouds to bring the thunder clouds awake and to bring the rain to the land, and really dismissed what I had said. And I was really confused. I actually have a photograph of my sister and I at the event with my parents, and everyone is smiling and having fun, and I’m not. I’m not unhappy or angry, I’m just in my own world. So it’s something I just remember in a very embodied way.

Osprey: And I was disturbed that my parents didn’t believe me. So I just got really quiet and silent. And then right before we left, someone, and again, I asked my mother later and it was not so clear for her. But a man looked me in the eye, got down on my level, and I shared what had happened and he told me yes. I don’t remember anything else he said, but he confirmed that the arrow was in my belly, and then I relaxed. And then I never spoke about it again, ever, given the response from my parents. But it deeply impacted my sense, even at the young age that I was, that there were other realities. Something else was going on in the world. I didn’t have the words for it, I was three, but of course I remember it completely at a body level and remember the experience. And then later, of course, much, much later realised, wow, that was really quite amazing. And to think that this was a normal experience and how I had accepted it, and then it relates to many other parts of the first chapter that have to do with worldviews and as I mentioned, our understanding of our place in creation. So, yes, that’s that story.

Manda: Yes. And our sense of time. There’s a beautiful bit at the beginning where you’re looking up at Orion, actually, you look up at the Great Bear, but you discuss the fact that certain of the stars in Orion are… Tell us about that. It’s better coming from you than from me. Talk about stars and timelines because I found your concept of time really interesting.

Osprey: Thank you for asking. The book starts with an incident I had with the climate crisis, living here in California with the fires and just how incredibly devastating some of the fires have been here. People have lost their lives, huge areas just scorched. And a particular day where the sky was literally orange black at noon and a really apocalyptic feeling, which it is. Anyway, I go out, when the air cleared out to the ocean cliffs here on the California coast, to breathe in the fresh air and look up at the stars. And the stars become and have been for me an avenue to perspective, and to opening my mind to other ways of knowing and thinking. And I then begin on a reflection about time and as you mentioned, looking at different constellations. That we all know scientifically that the stars are different distances from the Earth, so when we’re actually looking at one of the stars, the amount of time in light years it takes to come to Earth varies. So if you look at a particular constellation like the Big Dipper or Orion, there are so many light years that that particular constellation of stars is coming to the Earth, and they’re not the same. And so it begins a reflection of how can we be standing in one place looking at, in this case a constellation of stars, and realising we’re seeing different timelines all at once. And the reason I bring up this issue around time is that we know time bends and changes in space. It’s not linear.

Osprey: And why I’m bringing this up is because of the time riddle that we’re in, specifically around the fact that we are in a climate and environmental crisis that nature is in charge of, humans are not. Physics is demanding this. The Earth is telling us that we are not living here in harmony with her, and she is working to balance herself through droughts and floods and all the climatic changes that we’re experiencing. And that is her way of healing herself. And that has a timeline to it that is rapidly increasing, that we must urgently address. And at the same time, we also know why we’re in a crisis and we need to act urgently. You know, I have found that to deeply understand the crisis and to transform ourselves, to address it at the speed and scale we need to means transforming ourselves, which is slowing down and looking differently at things, and inviting other ways of knowing. And appreciating how to grow food, which takes time, and not just going to the grocery store. And some of the things that we need to do to remove ourselves from the overconsumption reality and the push of capitalism and the demands of grinding ourselves at work and all of these things that actually perpetuate the crisis. So we’re in a time riddle where we need to move quickly but slowly at the same time. And so this is why I wanted to look at how do we actually be in one place but invite different timelines into our reality?

Manda: Brilliant. So I have two questions that immediately arise. I’m going to ask them both. And you can decide what order you want to look in. As a three year old, a thunder Arrow arrived in your body and I am with my shamanic mind view, thinking that’s not an accident. And you have this magical thing inside you. And the fact that your parents think it’s an imaginary arrow is a Western view that is broadly irrelevant. To what extent, as you were growing up, were you aware of a sense of seeing the world differently, if at all? And how much did that capacity to see the world with the Thunder Arrow inside you, do you think led you to set up the Women’s Earth and Climate Action Network? Because you set it up 15 years ago, you don’t look that old to me. You’re in the fossil fuel Non-Proliferation treaty and a whole bunch of other things; you’ve been really active on behalf of what I would call ‘the all that is’, the web of life, it sounds to me pretty much all your life. First of all, is that true? And second, do you link it to the Thunder Arrow? Or am I simply projecting my desire for magical stuff to happen?

Osprey: Yes. This has been my life’s vision. My earliest campaign was to protect the redwood forests in Northern California when I was in high school. My parents were divorced when I was ten, and I then moved with my sister and my mother to the town of Mendocino from San Francisco, because my mother was figuring out how, as a single mom, to raise two kids on her own. So we moved to a beautiful, beautiful small town called Mendocino on the coast of California, about four hours north of San Francisco. And I mentioned this because that’s when I got introduced to the redwood forests and they became my family. We had other disruptions in our family, so for me going to nature was my place of home, my place of solace. And really, even though I did not know about indigenous cultures or my own indigenous roots from pre-colonial, pre patriarchal times, there was this connection with the land that was very real for me and a place for healing. And within that context, really falling in love with the redwood trees and then finding out they were being logged.

Osprey: And I had seen some clear cut logging, and then it really brought forth the question very early on, like, how could these beautiful places, these places of healing and holiness and just the magnificence of life be just, as far as the eye could see, just mowed down with stumps. Like, what were humans doing? So these are some of the first instances I realised something’s really not right with the world here. And that really began a lot of journeying around fighting for the land, for the earth and different campaigns. And then later it became also understanding more about colonisation and environmental racism. These ideas, of course, as you go on your journey, begin to unfold into the interconnection of a lot of interlocking oppressions. And anyhow it’s been sort of my lifelong quest to feel this deep feeling of the land and justice for people of the land. And I don’t know if I’ve ever attributed it directly to the Thunder Arrow. You’re the first person who’s really actually said that so directly as a connection. So I will invite that idea. I will invite that idea.

Manda: Yay! Let me know if your dreams change or something happens. I would be very interested. So I want to move on to the Women’s Earth and Climate Action Network in a moment, but before we get there, I’m really interested in this concept of splitting timelines, time being not linear. Although within our culture we view it as such, it quite clearly isn’t. But in a practical sense, it seems to me you’re one of the few people I’ve ever spoken to who has the broad picture. You know we’re in a poly crisis, you know that we need to change our value system, our worldview. And that we can only do that incrementally. Basically, you were essentially saying what Bayo Akomolafe says, which is ‘the times are urgent; we must slow down’. You seem to me to have many hats, and I’m guessing potential email overwhelm, where the tsunami of your email in tray just never stops, and you have an endless number of meetings to do and things to do. And it sounds as if you’re supporting people occasionally who are in deep crisis, people who are standing right at the forefront of trying to prevent pipelines or stop logging or all of the things that are actually quite dangerous. How do you personally find the heart space to connect to the Land and the All That Is, while juggling all of the other hats and balls and flaming chainsaws that are around you?

Osprey: Mm. That’s a beautiful question, and one that I think about on a regular basis and work to balance and manage, sometimes better than other times. And I think, to sort of tug at this question a little bit, I would say that one of the things I’m very passionate about is how to be in these broader conversations that you and I are having today, where we’re really exploring human consciousness, our meaning of life, our understanding of ideologies, our understanding of who we are as human beings in the earth lineage. You know, these broader conversations which are essential, because the deeper we go here, in my perspective, then when we actually do things like try to stop a logging operation or stop a fossil fuel pipeline, or go to the UN climate talks and negotiate with governments to do less harm, or we also meet with financial institutions. When I have all this background and depth that I’m attempting to come from, the information that then is being developed in the programs or projects or campaign has that DNA in it. And I’m very, very interested in the fact of not the doing only, but the how and the DNA in it. And so if we can get these worldviews like the earth is alive, that we have an animate cosmology, that nature has rights equal to human rights. And how do we take these systems and ideologies of being in harmony with nature and an animate earth, and our place in the web of life, and imbue that innately into a policy, even if it sounds very different than what we’re talking about here, I feel like that’s one of one way we can develop transformation of how humans are living with each other in the land.

Osprey: So it’s very important to me to do both, which is what you were getting at. Like how it’s so important to have these spiritual practices, whatever they are, in communion with the land. And make sure that I’m reading and studying thought leaders and being with my indigenous mentors and other systems thinkers. And then how to then on a very practical daily basis, put that into the work that we do. So that’s one part of responding to your question. Then the other part is ensuring that I, and my team, my small staff who are wonderful, that we have time to walk in nature, that we have practices that bring us into balance with the land. And without that, I don’t know how I personally would go forward. Like I have places I go at least once or twice a week and just listen to the forest or be out on the lake, because I’m not sure how else I could hear what I’m supposed to be doing and getting instructions from the land. But also getting balanced as a human being and staying embodied in what I believe in. And so I think it’s that. The last thing I’ll say is, I would be remiss to say that I’m doing this perfectly at all. Because sometimes it’s working really well, and other times there is a lot of overwhelm because we do work with particularly women on the front lines of different crises, and it can be really hard weeks.

Osprey: I mean, people are in emergency and they really need your help right now and there isn’t later and no, I’m really glad you want to go for a walk in the forest, but I need you right now to do this, that and the other. And of course that happens. And there can be some pretty hectic times. But I also feel we’re in the process of decolonising ourselves and removing ourselves from that hecticness. But it’s not over. And I feel as a white person, I’m not like some wealthy, privileged person, but no matter what, I’m a white person and that means I have privilege, I have access, and I’m going to put everything I have into the project of healing communities and our earth. So, you know, if that means we all have to tough it out sometimes, for me, that’s that’s part of my belief system it’s not everybody’s. But we’re not in in times that are well and so there’s going to be a grind sometimes because the, the system has to balance itself. And I’m going to throw myself into that at times and do so happily. Maybe not with a smile, but happily do it because I think it’s the right thing to do.

Manda: Right. Do it willingly, and then you can recharge your batteries on the lake or with the trees or in whatever way you can afterwards.

Osprey: Yeah. It’s not always about being comfortable, whether it’s a comfortable conversation or comfortable activity. Those of us who have more privilege, it’s okay for us to be uncomfortable and it’s part of our healing and growing and part of reparations. And I don’t mean like torturing ourselves or hurting our bodies, I’m not being ridiculous here, but I mean there’s going to be some discomfort in the system. And I think that that’s a positive part of this process.

Manda: That is really beautiful. I’m tempted to ask for examples of that, but I think we probably haven’t got time. We might get back to that. In the meantime, you started WECAN, Women’s Earth and Climate Action Network, back in 2009. So can you tell us a little bit about what led you to create something, the sense of global vision that it takes to set that up really leaves me awestruck. And then what it is you do, in edited highlight, because clearly we could spend the next six weeks talking about that. But give us a flavour of some of the things that you do and perhaps where you see it going.

Osprey: Yeah. Well, the short version is that, as we’ve been discussing, I’ve been very dedicated to this lifelong project, like many people, of what are we going to do with the dire conditions that humans have created on the Earth? And I would also say the amazing things that humans are doing. It’s such an unusual time because there’s so much peril but so much promise. I mean, the fact that we are even having this conversation, maybe a decade ago people wouldn’t even know what we were talking about, to just be so esoteric and strange. We couldn’t even say decolonised or other ways of knowing; no one would know what we were attempting to venture into those kind of conversations. So we’ve come a long ways, and I’m thrilled with so much with what is happening. But again, nevertheless we are looking at mass extinction. We’re looking at particularly indigenous black and brown communities and those in the global South suffering the worst impacts of the climate crisis and environmental degradation. People who have done the least to harm the Earth are being harmed the most. There’s a lot of injustice. And so this, as I say, has been a concern all my life. And then a particular moment is when the Obama administration here in the United States came into office. There was the climate negotiations in Copenhagen that year.

Manda: Oh, yes. They were a disaster.

Osprey: And there was a lot of hope that there would be a change, not just because of Obama, but the moment and people becoming more aware of the climate crisis. And as we all know, nothing major happened that was significant enough to meet the crisis at hand. And it was after that, I was actually walking in the redwood forests. And usually I go there for healing and calm, and I did not feel healing and calm. I felt like a screaming from the earth. And I pretty much within a short period of time just stopped everything I was doing. I was doing artwork at the time and other teaching, and I started researching and I found that one of the gaps is that women were and are leading so much of these movements for climate and social justice and environmental justice and doing incredible work, impacted the most because of gender inequality. And so there was the inequality and the impact to women that really concerned me, but also that their story was not being told about all that women were doing. And so it is now more of a space that is out there in our movements, about the relationship between the nexus of gender and climate.

Osprey: But at the time, there were other groups doing it we were certainly not the first. But it wasn’t being visiblized or understood. I won’t go on and on about all the statistics, but not only is it morally correct that we have gender responsive climate policies uplift, not just women, but gender diverse leaders, because I think we have to talk beyond binaries of men and women. But that that there was so much more needed to visualise, to invest in and lift up this leadership because it’s essential. And I’ll just say 1 or 2 stats so that it’s not vague. There’s something called the Women’s Political Empowerment Index, which is basically an index that shows country by country what kind of agency women have in social contexts and political contexts, freedom of choice and freedoms to express themselves in every sector. The Women’s Political Empowerment Index. And in the study that we have, it shows that just with a one unit increase in this index, it leads to an 11.51% decrease in carbon emissions. And it’s really hard to find something, anything over 10% that actually decreases carbon emissions.

Osprey: And so it’s really amazing to see what women’s leadership can do. And of course, the climate crisis is not all about carbon emission reductions. That’s just one piece of it. But still it’s a really powerful indicator. And we could talk about food production and water security. So many of these programs depend on women who are caring for their families, caring for the land. And just to give one last idea so people can recall this, which is during the height of the Covid 19 pandemic, countries that were led by women fared far better with their populations than countries led by men. And so this fact of women leadership is huge. It is a factor that we must keep bringing into the equation and making sure that women are at decision making tables, that they’re funded. That gender diverse leaders and women continue to be at the core of these social and environmental and political discussions so that we have justice and we have good solutions. And again, just to be clear, it’s not about putting men down. It’s about women lifting up and really striving for egalitarian societies. That’s what we’re really talking about here.

Manda: Gosh, that opens up so much.

Osprey: And I didn’t really address, actually I just want to say a few things about WECAN itself. I mentioned a little bit earlier, but just to recap briefly, we do work at a wide range of topics as you’ve talked about. So looking at short term change and long term change I think is really important so that we do get this DNA embedded in some of the work. But we work in different countries in the world, and we do a lot of work around stopping harms, like stopping fossil fuel projects, stopping deforestation. And on the other end, you know, how do we have a just transition? What does a just transition actually look like? How do we protect indigenous rights and human rights? How do we protect women’s rights? How do we have the results of where we’re going really reflect social, environmental and economic justice. And so building the world we want is equal to also dismantling these harmful structures. And to name them explicitly, we’re looking at dismantling colonisation, patriarchy, racism and capitalism and really naming those systems of oppression. And I would add, right now, given the situation in Gaza, as well as militarisation and imperialism. And how all those different systems are interlocking, and this is why we have to go to root causes. Because if I could wave a magical wand, let’s say, and end the climate crisis tomorrow or the violence in Gaza, the fact is those systems of colonisation and racism and patriarchy that drive us into an extractive economy, that drive us into harming others, that drive white supremacy, wouldn’t end. So we have to do both. Where people are dying and we have to immediately get on the streets and call the governments and meet with financial institutions, whatever we’re doing to stop the harm. But we also have to keep going upstream and have a systemic analysis and systemic plan for change.

Manda: Yes. Goodness. Okay. Even more possible routes. So I have a strategic question, in a way. You’re on the executive committee for the Global Alliance for the Rights of Nature. I’d like to talk a little bit about that. And on the steering committee for the Fossil Fuel Non-Proliferation treaty. And you’ve got WECAN. And it seems to me that you are very likely talking at the top table at a lot of the the big meetings that the rest of us kind of see floating past on Twitter. And my perception of particularly, say, the COP process. COP 26, I had a bit of hope for, partly because it was in my hometown of Glasgow and I thought maybe. Nicola Sturgeon, a woman leader was there and I thought she does kind of get it. And yet there were more people from the fossil fuel companies in the areas that mattered than the totality of everybody else. Within two months, Fossil Fuel Nation had declared war on its neighbour, Russia, against Ukraine, which gave them cover for hiking prices spectacularly and they haven’t stopped since. And you and I, and I imagine most of the people listening, if not all of the people listening, are aware that we need the equities that you were talking about. Of gender and gender diversity and race and class and human and more than human. We need to stop all of the hierarchical systems.

Manda: But the people in the hierarchical systems who are almost exclusively straight white men, and most of them quite old, are really happy where they are. And they have created systems that are designed to perpetuate the systems, and they do it very well. I have conversations quite often with people who go, the system is broken and we think, no, the system is not broken. The system is doing exactly what the system was designed to do, and it’s doing it really well. It’s just that people are beginning to realise that what the system is designed to do is to destroy everything in pursuit of the people at the top becoming unbelievably and obscenely wealthy. In your conversations with the kind of people who think becoming unbelievably and obscenely wealthy is their job, do you see any sign that they actually get that dismantling the system is going to have to happen if their children are going to have an inhabitable planet?

Osprey: It’s such a good inquiry. I would say that I think any human being at any point has the opportunity to change and transform. And what that moment is, is unique to that person. And we never know what that is. And I say that because I’m sort of a die hard optimist and that we should just go as hard as we can forever for our beautiful mother planet and the web of life and all sentient beings. And so I don’t believe in ever giving up on any one or any thing, because we can’t afford to. I think it also is an outsized part of privilege to think that we can ever give up, because people’s lives are on the line and our ecosystems are on the line. So not sort of in a Pollyanna way of, oh, you know, something will work out and it’s all going to be okay. I don’t mean that, but like I don’t feel we have the right to give up.

Manda: I’m with you on that.

Osprey: So let’s think about how everyone can transform. So starting there, just giving everyone a chance. That said, just to be very practical, I was thinking when I was in Dubai at the last COP, we’ve been at the COPS for over a decade and people often say, why are you going? Nothing can happen there. But, you know, I don’t suggest everyone go to the COP. It is not where all these things are going to get resolved by a long shot. However, the saying ‘if you’re not at the table, you’re on the menu’ is also real. And the fact is, those of us deeply involved in the negotiations, there’s a lot going on that is not seen that is very, very critical going on. And we have to remember that civil society, along with vulnerable countries, were the ones who pushed through during the Paris climate agreement, the 1.5 degree guardrail, which has been critical to our advocacy and to all kinds of things. We did get the Loss and Damage Fund, which is a form of climate justice in the COP that was in Egypt. And last year at the COP, we did push through getting fossil fuels and phasing out fossil fuels into the conversation, dragging it there centre stage, which governments didn’t want to do. All of these things are not well done and there’s all kinds of problems. So it’s not like all the work we do at WECAN, by a long shot, I would never want to make our organisation just do that, but it has its place. And to get to your question, yes, there are points that are really key.

Osprey: As an example, we brought a report from WECAN to the negotiations called the difference between net zero and real zero, which I don’t want to go into right now, but how we actually have to have real zero versus net zero analysis. And we brought that to negotiators and had deep discussions with them about it for the Just Transition working group, and really talking to them about how carbon capture doesn’t work and all of these things, and converting some people maybe one by one. And so there are possibilities like that. Or we meet with financial institutions, meaning banks and asset management firms, who are doing harmful projects, maybe hurting an indigenous community. And we bring those indigenous leaders to go meet with them directly and say: you have policies around indigenous rights, you have policies around protecting ecological integrity in your institution, but you’re not following it. And this is why you need to do better due diligence. So I think one of the key leverages to change is that we have to talk to each other, no matter how uncomfortable this is, we have to not be in our silos and create exchanges where transformation can happen. I don’t think it’s the only thing we need to do, because I will equally get out on the street and protest things, and I’ve been arrested. So it’s an ecosystem of activities you need to happen. Some of that is like resistance movements, others are dialogue. You know, it’s a combination of things that we collectively need to do together in the ecosystem of activism for this change. And I think the part that is hard is, and I hesitate to say this, but just to not avoid part of what I think your question is getting at, is there are moments when I think, okay, there are people who need a lot more education and when exposed to a heartfelt conversation with facts, are in a place where they could actually make change from the inside of these institutions that are destroying all of us.

Osprey: And I do think there’s another grouping of them, I will leave them the chance to change, but the basic feeling is I don’t care. And that’s really hard. That’s heartbreaking and devastating to be in rooms where no matter what you say and do, for some reason that person or that corporation has decided that they’re part of the wealthy elite, and somehow they’re going to not have their children harmed. I don’t know how they wrestle with that. And somehow they’re going to have a bunker or whatever their vision is, that they’re going to be able to be behind a closed gate and have food and water and not be harmed by the climate crisis or social upheavals or who knows what. I don’t know how to look at that, but I know the feeling and that devastation and the sorrow and grief I feel when I’m in those spaces that, wow, they just don’t care. Because that’s the only thing I can think of. And it’s hard to wrestle with that. And I will just leave a prayer of light around that, because that’s tough.

Manda: I can imagine that’s extremely tough. And also I’m thinking because you have a spiritual basis and a spiritual practice, that energetically bringing yourself in a different energetic space into that place…I’m thinking out loud, and this is a somewhat unformed thought. Words are not going to work if somebody is so deeply in denial and fear, and one has to assume that at the core of their denial is absolute terror, but they have walled themselves off. They’re deep in the trauma culture. They’re deeply, deeply traumatised, probably for generations, and they can’t let themselves care. But if you come to them, and I am imagining you do, with the Thunder Arrow and the spirits of the redwoods and the lake and the ocean, and be fully alive in their presence, it seems to me that is most likely the thing that might reach them. That you could say all you like, you could show them pictures of dying children and it’s absolutely clearly not going to touch them. What’s happening in Gaza would not be happening if certain sectors of our population were capable of normal human empathy, I would suggest. But perhaps a way to connect with them is through the integrity of genuine earth connected feeling. Does that resonate at all? Or am I just off again on one of my slightly weird things?

Osprey: No, I think that’s absolutely a component of it. And also realising that there are many more people who do care and the more that we collect together, it’s sort of like the idea of adding in more probiotics, let’s say, that crowd out the stuff that should not be out of balance. So I kind of see us as growing our probiotic movement.

Manda: Fantastic. Yes. Brilliant. Okay, let’s follow that road a little bit. Because the book I’m about to publish, we are about to publish, I’m calling it a mytho political thriller. So mythological, political, put together because I believe that we need a new mythology. But the best way to get that out is embodied in other structures and other narrative genres. Actually, I hadn’t read your book at the point when I called it that, and I think you’re doing this, because you’re looking at origin stories from around the world, and you’re looking really at changing the worldview of the trauma culture. And this is absolutely my internal project at the moment, is how do we take our trauma culture, which is traumatised for generations in the islands of Britain, I would say 2000 years. The Roman invasion brought the trauma culture to what was otherwise, I understand, an initiation culture. But Rome didn’t invent that, you know, they were traumatised. We’ve probably been traumatised since agriculture became a thing, and my current thinking is that the trauma arose before the agriculture, because you can only own land and animals if you’re already cut off from the web of life. It’s not a thing otherwise.

Manda: So we’re in the trauma culture, we need to become an initiation culture. My thinking up till now has been we need a new mythology because our culture is so steeped in Abrahamic, weird patriarchal mythologies and the old mythologies are not going to be taken on board by people who spend most of their time on the internet. You know, scrolling, doom scrolling, good scrolling, porn scrolling, whatever they’re scrolling. We need a new kind of mythology that speaks to the 21st century, and yet is grounded in the All That Is. But then I read your book and you’ve got some really beautiful origin stories, and I’m wondering whether you see the creation of new mythologies, new origin stories, new concepts of who we are and how we relate resonating in people of our culture? Is it beginning to seep through? Are people taking them on board in ways that they actually absorb them at a heart level, rather than simply viewing them at a head level? Does that make sense as a question?

Osprey: Yeah, I think it’s a really important question. And the simple answer is yes, I do think so. And I will share a little bit about that. I certainly have experienced it even more since publishing my book, it’s only been out like three months, and I’ve already had so many marvellous conversations about not exactly this topic, but close enough. And I wouldn’t just say it’s like ‘the youth’, I don’t think so, it’s people of all ages. I don’t think it’s specific to any demographic or age group or anything like that. I think that people who are aware that our systems are working as they should, as you mentioned earlier, which is very harmful to most people, and disconnecting us from the land and a deeper sense of meaning. You know, we’re human beings, we feel, we are tuned in to the fact of the web of life, whether we’re conscious of it or not. It still is innately within us, which is why the book is The Story Is In Our Bones. I mean, we know this in our deep and our embodied experience on this planet. So I think it does bring the question forward of the deeper meaning and deeper cosmologies and a deeper understanding of what is life and what are we doing here and why are we harming each other and the earth? I mean, we see our students protesting all over the world and mobilising.

Osprey: So, yeah, I think people are having these questions. And the origin story, for a very practical reason, even though I give a lot of different origin stories around the world, I actually start with talking about the scientific origin story, because it, to me is a doorway into the question you asked. Like, how do we sort of normalise and socialise this idea of who we are? And I really love looking at how we could talk so much more and bring into our daily worlds the reality that we do come from the stars. This is not a metaphor or a mythology, the fact is in the beginning of our solar system and I won’t give the scientific creation story we all know from grammar school or where we first learned. You know, how the planets formed and the stars formed, and how stardust came to the Earth and created all the elements, and then the different first cells started and all of that story, which I do share to some degree in the opening chapters of my book. And I think I learned that I’m guessing in third grade, I don’t remember, but grammar school, okay?

Osprey: And then maybe it gets touched upon in some other science classes. And I was studying environmental studies, but it really is left alone. Like we all know that and we move on. Now, if we think about a lot of place based peoples or indigenous cultures, not all of them, but often on an annual basis there’s some sort of cultural practices or ceremonies or dances or songs created to regenerating that story and talking about it in some way, again and again and again and again, to renew our remembrance of who we are in the earth lineage. And that perspective turns out to me to be gigantic, in how we perceive ourselves and create our codes of conduct with nature, because every year we are, if you want to use the term, initiating ourselves back into the story of life, back into the story of the universe, remembering, oh my gosh, this is just pretty phenomenal that we’re even here. And that through that story, we remember scientifically but also spiritually and every other way, that literally the water, the forest, the animals that we share the earth with are our relatives. When we look at evolution, we are part and particle of this evolutionary story. And so it changes how we see the world as an animate cosmology.

Osprey: And that Mother Earth and everyone else we share this planet with is literally our relatives, then how we treat our relatives becomes the question. Versus the current modern social constructs and worldviews that humans are above nature and we have supremacy over, and all of these things that have led to the extractive economy and so much violence. And so I think when we knit together these stories of where we come from in these origin stories, and have them be talked about on a regular basis, it really transforms how we live with one another in the Earth and also addresses this terrible fracture that has happened and a feeling for most people in modern society of being orphaned from the earth. And I think that orphanage expresses itself in depression and violence and trauma and all of these things that lead to negative behaviour, instead of us being a life enhancing species, feeds us to be over consuming, trying to fill ourselves up, trying to compensate for this false sense of separation. And so this is why these origin stories are so important, to continue to renew on a regular basis our understanding of who we are and our place in creation and our responsibility to the web of life.

Manda: Yes, that is so beautiful. I love your concept of our trauma culture as being orphaned. We’ve lost that connection to our mother and our sky father, and that sense that we are an integral part of the web of life. You’re on the executive committee for the Global Alliance for the Rights of Nature. You’re working a lot with people who are creating ecological laws to give rivers, particularly, personhood and rights. And I’m wondering again, this is maybe the same question asked slightly differently, but I see a lot of people who understand at a head level that they are an integral part of the web of life. They can kind of get that. It’s an idea and it works really well and it doesn’t translate to a change in behaviour. It hasn’t settled at a heart level where they feel, where they know themselves, where they actually can go out and connect to the web of life and feel that sense of agency and connection and being and belonging that is real. It’s an idea, it’s not a lived reality. I am imagining that you work with a lot of indigenous people who have maintained that initiation culture, who have been traumatised, but have not become a trauma culture as a result. I’m kind of interested to know how they manage not to and that can we replicate that out? But you’re working with people for whom the river is their grandmother or their ancestor, and that traumatising the river would be unthinkable. So you’re on the executive committee for the Global Alliance for the Rights of Nature. And it seems reading your book and listening to other podcasts with you, that there’s actually quite a lot of movement in this area. That we’re getting legal action giving actual personhood to rivers, particularly. Tell us a little bit about that. Tell us whatever you think is working best within that, and whether there are things that the people listening can do to support that process.

Osprey: Thank you for bringing that up. I think that one of the beautiful things about the Rights of Nature movement is it really gets at what we’ve been talking about throughout this podcast, which is like how do we generate a cultural change with also some of the policy work we’re doing? And I think Rights of Nature really works at that nexus. And so it’s basically the idea that nature already has rights. In other words, if we don’t follow the natural laws of the earth, which we’re not, we’re not going to be here. But what it does, it actually is a form of Earth jurisprudence that has been developed over many years to actually show in a court of law what are rights of nature. Meaning giving forests and rivers and mountains and the climate rights, so that they can be protected in our legal systems. Because the legal systems are what we have now. This is what we have to work with as we move from, as you’ve been saying a traumatised, not well culture and society globally, to something that we’re all really calling forth from deep in our hearts and our psyches. And rights of nature, is a really great tool to get from one point to the other. And so it’s been very exciting to be a part of this movement, for over a decade now. And it’s one of the fastest growing environmental movements in the world. And people are realising that we need to have different environmental laws because the ones we have don’t work.

Osprey: And the main reason they don’t work is because of the view that the land is property. We need to get nature and Mother Earth out of the marketplace and stop the commodification and financialization of nature, and see nature as a living, beautiful, sentient being that nature is. And I think I will just share a story, but also say it’s not just an idea. We have many cases that have been won in the United States, over two dozen. Ecuador became the first country in the world in 2008 to bring rights of nature into their constitutions, and have now won cases using rights of nature laws. I was just a few weeks ago at the Goldman Prize Awards, and one of the award winners was a woman from Spain who used rights of nature to protect a river in Spain. And I believe there’s over 39 countries now around the world who are working with rights of nature law. So this is very real, it’s not just conceptual. But what I’m thinking now is of a very beautiful story where I was on a fact finding mission in New Zealand, where the Whanganui River has been protected by the Maori people and an agreement with the state. So there is a governance structure in which there’s someone from the government and someone from the Whanganui tribe who steward the Whanganui River, and they see the river as their living ancestor.

Osprey: And when I went there, I was able to go to the Whanganui River with a beautiful Maori elder. And when we went to the river she sang this beautiful song and afterwards she took my hand and she said, we have a saying, here I am the river, and the river is me. I am the river, and the river is me. And it was just so beautiful to have that embodied sense of knowing that our bodies are primarily water and feeling all the rivers of the world, and how water is life, and that this literally is our relative, our ancestor. Sort of going back to what we were talking about earlier, about how we come from the elements in our evolutionary journey as a species, and to have a law that actually expresses that and honours life. And the river as an ancestor moved me so deeply. And I think that this rights of nature movement has the capacity to move us into the world that we are really wanting to live in, in which there’s respect and an understanding that we’re here to be life enhancing and to live in this beautiful, beautiful miracle of of this earth in a good way. And yes, there’s all kinds of struggles with it that we could talk about, but I think it’s a very exciting movement. And one of the pieces of the ecosystem of change that we could all participate in.

Manda: Fantastic. Thank you. I have kept you here long enough. This was such a glorious conversation. I would love another conversation sometime, because it feels like we’ve just scratched the surface of all that you’re doing. But in the meantime, Osprey Orielle Lake, thank you so much for the beautiful book you’ve written: The Story Is In Our Bones; How Worldviews and Climate Justice Can Remake a World in Crisis. I totally recommend that everybody buys it. It’s beautiful. So thank you for that. Thank you for all that you’re doing. And thank you for coming on to Accidental Gods podcast.

Osprey: Thank you so much for a wonderful conversation and all best to you.

Manda: Thank you. And that’s a wrap for another week. Huge thanks to Osprey for all that she is and does, and particularly for finding the time in the midst of everything else that she does to write a genuinely beautiful book. I know I’ve said this several times, but it is beautiful. It’s got so much depth, so many different layers, so many beautiful perspectives from the opening with that concept of the stars and the difference in the time frames, and the concept that time is not linear, that we are floating in the vastness of space, that we are one being in a great vast ocean of space and time, and we are an integral part of the web of life. And each of us is here for such a short flash of time, and yet we can extend it, play with it, move within it. And there is still time for us to reconsider who we are and where we came from, and how we begin to interact with the world and do things differently. Osprey is one of the few people I’ve had on the podcast who absolutely explicitly talks about ending capitalism and racism and injustice and inequality and misogyny and all of the other injustices that our hierarchical system perpetrates. And she doesn’t just talk about it, she actually lives the change. Honestly, you need to check out some of the websites. I put them in the show notes. Just the work done by any one of the organisations she works with and for would be amazing.

Manda: The fact that she’s in all of them and she had time to write the book leaves me completely gobsmacked, but in a good way. So if you want to support her, head out, buy her book, buy copies for your friends, hand them out, and more than anything else, read it. It is beautiful, it has great depth, it will I think help to shift you into a space where you can connect with the web of life, where the magic that seeps through all of the pages feels real. So go for it. You’ll enjoy it, I promise. And that’s it for this week.

Manda: Thanks as ever to Caro C for the music at the head and foot. To Alan Lowells of Airtight Studios for the production. To Anne Thomas for the transcripts. To Faith Tilleray for keeping everything moving, and for all the conversations that spark all of the ideas that make this podcast happen. And as ever, an enormous thanks to you for listening. If you know of anybody else who wants to be inspired about what’s possible, who wants to think more deeply about who we are and where we come from, and how we might be and belong in the world, then please do send them this link. And that’s it for now. See you next week. Thank you and goodbye.

You may also like these recent podcasts

Sit with the River, Breathe Sacred Smoke, Love with the World: Building a Bioregional world with Joe Brewer

How can Bioregionalism supplant the nation state as the natural unit of civilisation? Joe Brewer is living, breathing and teaching the ways we can work together with each other and the natural flows of water and life.

Solstice Meditation 2025 – Sun Stands Still – by Manda Scott

Here is a meditation for the shortest night of the year – the time when the sun stands still.

It doesn’t have to be at the moment of the solstice, it’s the connection that counts, the marking of the day. And you don’t have to limit yourself to one pass through – please feel free to explore this more deeply than one single iteration.

Thoughts from the Solstice Edge: Turning the Page on a Dying System with Manda Scott

As we head into the solstice- that moment when the sun stands still—whether you’re in the northern hemisphere where we have the longest day, or the southern, where it’s the longest night—this solstice feels like a moment of transformation.

Falling in Love with the Future – with author, musician, podcaster and futurenaut, Rob Hopkins

We need all 8 billion of us to Fall in Love with a Future we’d be proud to leave to the generations that come after us. So how do we do it?

STAY IN TOUCH

For a regular supply of ideas about humanity's next evolutionary step, insights into the thinking behind some of the podcasts, early updates on the guests we'll be having on the show - AND a free Water visualisation that will guide you through a deep immersion in water connection...sign up here.

(NB: This is a free newsletter - it's not joining up to the Membership! That's a nice, subtle pink button on the 'Join Us' page...)