Episode #172 Dancing with the Muppets of Cutthroat Island: Transforming Industry to create a genuine Green Revolution with Dr Simon Michaux

How much actual stuff do we have in the world compared to what we need to make the ‘Green Revolution’ happen? And how do we adjust our lives so that we can create the infrastructure we’ll need to take us to a post-carbon future?

This week’s guest is another of those recently elevated to my pantheon of people I Must Listen To whatever they say and however they say it and I am genuinely thrilled to welcome him onto the podcast.

Dr Simon Michaux has been a physicist and geologist. His PhD is in mining engineering and he worked for years in the mining industries in Australia. In 2015, he moved to Europe and became involved in urban mining, or reverse metallurgy, which is to say the recovery of essential minerals from existing waste – what we would call the beginnings of the circular economy – and from there, he moved to Scandinavia where he now works in the Geological Survey of Finland and is a regular advisor to the Finnish parliament.

From all of which you will gather that Simon is deeply embedded in the actual physicality of the world we inhabit – and, because he’s also committed to creating the future we want and need, he is growing ideas of the future we could inhabit. Of all the people I’ve encountered as I roam the digital web for ways we can shift our relationship with the living web, Simon is the one who has his finger on the actual logistics of what’s going on – he can list the reasons why most of the targets for our transition away from fossil fuels are simply logistically impossible. It’s not until you hear his crunching of the numbers that you begin to realise how much arm waving is going on in the corridors of power. How much raw self-delusion is being practice by the people who we still, at some deep subconscious level, trust to keep the show on the road. And I think we need to know this. It’s hard. It’s sobering. It’s shocking, on many levels, but if we aren’t grounded in reality then we’re not going to build forward So hold onto your seats – this isn’t easy, but we do need to know it. And then we need to plan our responses. Fast.

Episode #172

LINKS

Simon Michaux’s website

Resource Balanced Economy Paper

Assessment of the Extra Capacity Required of Alternative Energy Electrical Power Systems to Completely Replace Fossil Fuels

Answers to Hot Topics around the above report

Interview with Mark Mills of the Manhattan Institute

Video – What are the Raw Material Supply Bottlenecks to the Green Transition? The Need for a New Plan

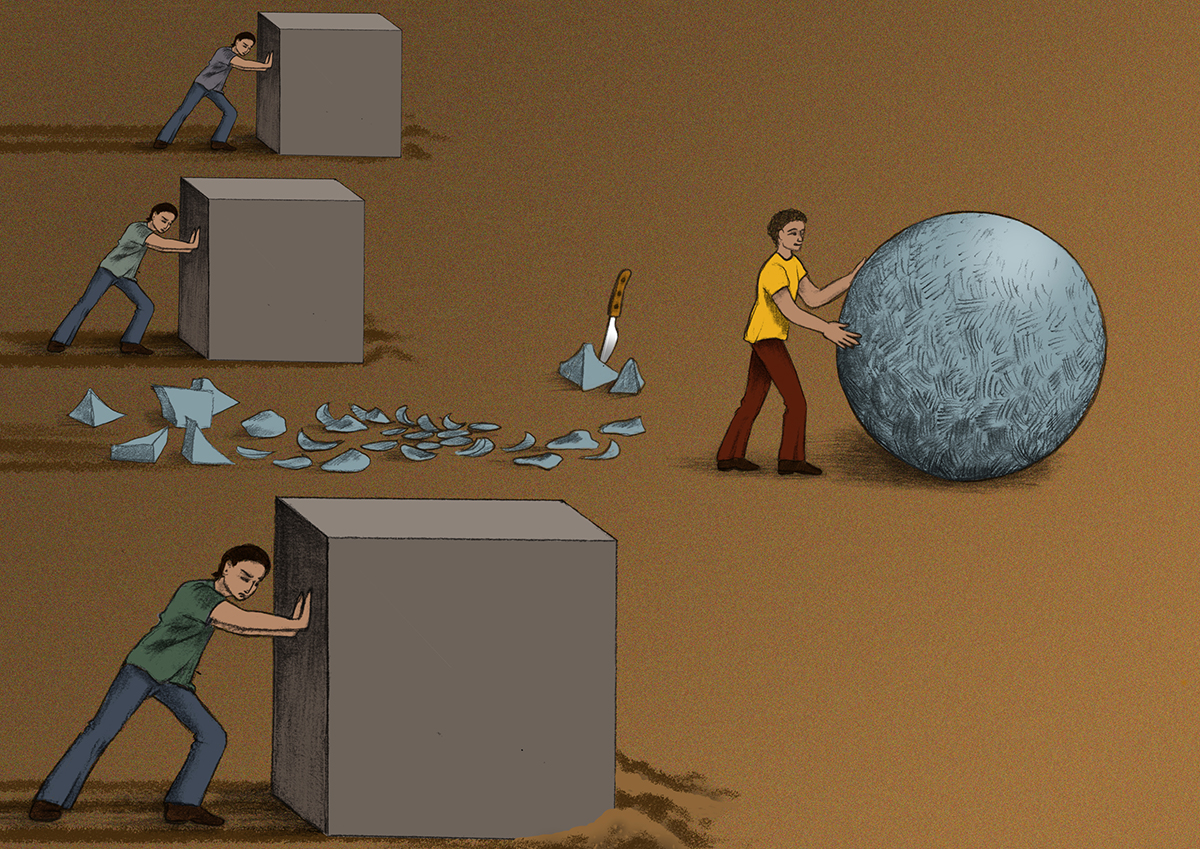

Thanks to Tania Michaux for the graphic.

In Conversation

Manda: This week’s guest is another of those I have elevated in my podcasting years to the pantheon of people I must listen to whatever they say, wherever and however they say it, and I am genuinely thrilled to welcome him onto this podcast. Dr. Simon Michaux has been a physicist and a geologist. His PhD is in mining engineering and he worked for years in the mining industry in Australia. And then, as you’ll hear, in 2015 he moved to Europe and became involved in urban mining or reverse metallurgy, which to those of us who don’t inhabit these worlds is probably best explained as the recovery of essential minerals from existing waste. And we would probably call it the beginnings of the circular economy. And from there, Simon moved to Scandinavia, where he now works in the Geological Survey of Finland and is a regular advisor to the Finnish Parliament. From all of which you will gather that Simon is deeply embedded in the actual physicality of the world we inhabit. And because he’s also deeply committed to finding a future that works, he understands the world that we could inhabit and how we could actually make it happen. Of all the people I’ve encountered as I roam the digital web, looking for ways that we can shift our relationship with the living web, Simon is the one who has his finger on the actual logistics of what’s going on.

Manda: He can list the reasons why most of the targets for our transition away from fossil fuels are simply logistically impossible. It’s not until you hear his crunching of the numbers, that you begin to realise how much arm waving is going on in the corridors of power. How much raw self-delusion is being practised by the people that we still, at some deep subconscious level, trust to keep the show on the road. And I think we need to know this. It’s hard, it’s sobering, it’s shocking on many levels. But if we aren’t grounded in reality, then we’re not going to be able to build a way forward. So hold on to your seats. This is not easy, but I really believe that we do need to know it. So people of the podcast, please welcome Dr. Simon Michaux, all the way from Finland.

Manda: Just to open up for everybody, Simon, by the time you hear this, will almost certainly have published a paper on the resource based economy. Which I think is going to open up the areas of discussion that this podcast is all about, in a way that people with power actually listen to. And so Simon’s here to unpick this. Thank you, Simon. We have snow. It’s almost Finnish out there just now, the snow of the sort that stops the UK in its tracks, because there’s two inches of snow and it’s never quite got below zero, but everything stopped. There we go. So it feels like Finland, it’s not quite -30 and freezing, freezing pipes in and out, but it’s close.

Simon: There’s a local joke here; you’re Finnished. You’ve been Finnished.

Manda: Finnished. Yeah, we get Finnished a lot easier than the Finns do. I don’t think it’s ever been -30 here. Anyway, we’re heading towards the resource based economy and we’re heading there via the concepts of energy blindness, materials blindness and minerals blindness. And then Simon Michaux’s hierarchy of needs and how we address them. So, Simon, thank you and welcome. I’m enormously grateful and it’s good to see you.

Simon: Nice to see you again.

Manda: Thank you again. Yes, this is version two people because I screwed up on version one. But the start of version one was lovely. We started talking about materials blindness and until I interrupted with a bunch of questions that were entirely unnecessary, you were telling us how you became aware of the materials and minerals and energy blindness of our entire culture, that needs to change. So can you kick us off with more or less the same again?

Simon: Okay, so I came from the Australian mining industry and I was working in research and development for a long time, 18 years. Then I joined the private sector and feasibility studies. So when I actually came to Europe, I was collecting information to show that the mining industry was entering into an era of business model that was very difficult. It’s going to be very difficult for the people who stay in it, and I didn’t think corporate leadership really understood. And their solution to everything was just to fire everyone and just wait till the market comes back. And that’s not going to work for much longer. They’re going to have to change the way they do things. Anyway, so I came to Europe to learn industrial recycling and I joined the University of Liege. And I used to attend these meetings in Brussels and Berlin, and listen to the European Commission tell us about their plans. And I came across the H2020 Research Project and the circular economy. And what blew me away was a series of blind spots. In Europe, we don’t do any mining. And in fact, it’s seen as dirty and unclean and unfashionable. However, everyone uses technology like computers and cars and that all comes from mining. But what happens is, we buy them off the market. They’re all made outside of Europe. And so there was just this General, how do you say, they were completely unaware that the raw materials weren’t being sourced in Europe. And the people there didn’t understand that and they hadn’t done anything like that for decades, so it wasn’t part of their thinking. They saw everything as an economic action, and so they were completely untethered to the realities of harvesting raw materials and then turning them into stuff.

Simon: Even though they were talking about the new energy future, there was absolutely no awareness of our current dependency on fossil fuels. And they’re still unaware. If you took away coal, for example, from planet Earth, all the manufacturing systems around the world, including China, would simply stop. To make a solar panel, you’ve got like a silicon wafer and you’ve got to heat that silicon up to 2200°C. At the moment, they use coking coal to do that. Now you can you can use other things, like biofuels or hydrogen, but to scale it up to actually do what coke and coal does for us, the planet cannot supply that much biomass. So the problem is not a new technology. We can’t have the raw materials to do it any other way. So take away coal, all our existing technology, including solar panels and wind turbines and electric vehicles and their batteries, will stop. And we haven’t got a substitute for that. And because we don’t like talking to the Chinese and they don’t like talking to us, this is never discussed. So we are chasing ourselves in circles, increasingly smaller circles, without actually realising that the monster in the room is not even looked at. So it really struck me as the leadership in the European Commission levels, but also everyone else I talked to, were oblivious to reality. They’re untethered from it. There was no feasibility study for macro scale transition away from fossil fuels. It just didn’t exist. And there were no numbers. What I mean by that, what I wanted to see after 14 years of talking about it – 14 years!! – And the most amazing amount of money that’s been thrown around on this. You Muppets!

Manda: Hang on, 14 years of them talking about it or 14 years of them talking about it in your company?

Simon: No, no in Europe. 2008 is when the circular economy was launched.

Manda: Oh, really? It wasn’t a thing before then?

Simon: Not really. It was an idea that wasn’t formalised. What they realised was that they were worried that European businesses were in trouble. Certain core businesses needed raw materials that were being sourced from outside of Europe. But it’s not the raw materials they’re worried about, it was actually the businesses themselves. So even at its inception, they were not actually interested in the raw materials. And now they’ve got what’s called the critical Raw materials map. And so economic importance and economic scarcity. That map is used by everyone to determine this is what we should be looking at. You know, there’s some some metals in there that are in the critical zone, the critical stuff coloured red and everything around it is blue. However, that’s not looking to the future. That’s actually calculating for the previous four years of data. So while the system is still running on fossil fuels, that’s what’s critical. Take fossil fuels away and none of that exists anymore.

Manda: Let’s interrupt briefly. What’s critical? What is it? What do they consider critical? Critical as in it’s becoming hard to get? Or critical as in the price is going to double? You said everything was an economic assessment. Is this just they’re becoming too expensive.

Simon: Too expensive, but also scarcity. So you’ve got one axis, which is economic importance, something that we really need, right? You know, we really need steel, for example, we really need copper. And then you’ve got economic importance, then you’ve got economic scarcity or a scarcity profile. And there’s like a formula they use for that. And scarcity is supposed to be reflected by price going up, but the price is going up because it’s scarce.

Manda: Okay, Yeah, that’s market fundamentals working as intended. But scarce means as in there isn’t very much left? I remember you saying previously that that the planet is basically made of minerals. It’s not that they’re not there. The whole of the Andes has got copper in it. It’s just that it’s really hard to get. Also, I think we don’t want to level the Andes. So scarcity for them, for the people doing these assessments, is that some intern somewhere has gone and looked at the prices. Has anybody at any point gone and looked at what it takes to dig it out of the ground, how deep the mines are, how big the mines are, what we’re actually accessing.

Simon: So that is the missing element, right? Some people have looked at it in Australia. They have indeed looked at it because that’s their end of the business. And the mining productivity index decreased about 50% between 2001 and 2012. What that meant was twice the amount of work, physical work, had to be done to get the same unit of metal out of the ground.

Manda: So was it twice as expensive as a result?

Simon: The prices did go up okay, but prices are highly sort of volatile and there’s a lot of speculation and above ground forces that do that. Mining costs have been going through the roof, across the board. And there was a blow out in 2005 of metal price. And I think that is related to a signature that started in the oil industry.

Manda: You want to say more about that?

Simon: Yeah, sure. So there’s a chart that shows a blow-out of metal prices in January 2005

Manda: As in spike is a blow-out, when it goes up or when it goes down?

Simon: Yeah, it goes up. The price of everything went up a lot. And we’re talking about all base metals, precious metals, oil, gas and coal. And that put the system under such pressure that three years later, we had the global financial crisis. So this is actually the genesis of the GFC. Now, what happened in January 2005, global oil production plateaued, like it rolled over and it plateaued, but demand continued to increase. So what happened was the swing producer at the time, Saudi Arabia, I believe, was asked to raise oil production like they always claimed they could and they couldn’t. The reason I say they couldn’t, they brought on 146% increase of rig count. That is 146% more rigs drilling for oil on their deposits. And they brought them on as quickly as possible, but they still had a 4% decrease in production. So that meant all their conventional oil reserves weren’t producing. And they’ve gone up since then, but now they’ve actually rolled over and they’ve peaked and they’re now declining. But they’re now sweating their deposit as fast as they can, to maintain production targets. So for a short period of time, the Saudis could not meet oil supply and demand constraints.

Manda: Quick question. Why did demand go up? Is demand just rising and rising because we live in an economy that has to grow and it has to grow by increasing its consumption of energy?

Simon: Yes. And also population increases every year. And every economy has the metric of 2% growth. And if we’re not growing, something’s wrong.

Manda: And growing equals use more energy. It’s impossible to grow without there being more energy input.

Simon: Oil in particular. GDP correlates very strongly with oil consumption. So total liquids consumption is what it is now. So what happened was the demand continued to rise, but supply had to stabilise. So for a period of time, supply and demand separated. And that provided the conditions for an oil price spike, like a speculative bubble. And so the price rocketed up and the the marker for the start of the global financial crisis, is when the oil price peaked and then it crashed. So we can’t take this anymore and the GFC kicked off, and it was blamed on the weakest link breaking, which at the time was American real estate, in what was called the subprime mortgage market. That was just the weakest link. But the whole system was being cooked, for three years it was being cooked before it broke.

Manda: Kind of like ours is just now.

Simon: Well, funny you should mention that. We fixed it by printing money. Quantitative easing. And that’s how it all suddenly went away and everything got better. But since then, we’ve had to put more and more money in to keep the system going. And I believe the system died in 2008. And we’ve been, it’s like, what’s the phrase? The dinosaur is dead, but the brain doesn’t know it yet because the last of the blood is still being pumped up the neck.

Manda: Right, Right. Yeah. I always have this vision of Wile E Coyote out over the canyon, running out over thin air. And you just haven’t quite looked down yet, but, yeah, it’s the same idea. So basically we’ve got an economic system that is on life support and being kept apparently in zombie form, by us pumping imaginary money. I mean, the money isn’t tethered to anything real anymore.

Simon: They’re making it up, but the parcels of money they’re putting in are getting larger and larger and larger. And when you compare historically what’s been done in the past to what’s being done now; if you were to adjust for inflation and bring everything into line, I did this in one of my papers; the race to the moon, like the landing Neil Armstrong on the moon. That cost $145 Billion in 2018 numbers, in 2018 USD. We we put in the war machine, I think it was like 3 or 4 trillion for the Vietnam, Afghanistan and the Iraq wars. Really. And QE one, two and three, that was like a couple of trillion on top of that. But the COVID package of 2020, that was 5.4 trillion on its own.

Manda: Right.

Simon: Right. So the numbers just don’t mean anything anymore.

Manda: Well, they don’t do they.

Simon: No. And then COVID happened and now we’re on the razor’s edge, I think, of the next economic downturn. And they can’t print money their way out of this, because they’re now saturated. If they tried printing money now, they would trigger a hyper inflationary spiral. They’ve prevented it so far by controlling both sides of the balance sheet and keeping certain assets off the balance sheet. And that’s how we’ve actually not been subject to hyper inflation. But I think now it’s time.

Manda: Okay, we could go down that route, but I spend quite a lot of time on the podcast talking about economics. Let’s leave that for potentially later. And let’s come back to, because what really always struck me about listening with anything that you’ve been doing, is nailing the numbers in ways that are irrefutable. So let’s go back to the Muppets in the EU, who are trying to find out how European business can keep going. And they haven’t really got their heads around what’s actually going on, but they have an idea that they want a circular economy where the output of one business becomes the input to the other business, and where recycling is 100% and we’ve just discovered perpetual motion because it doesn’t take any energy. Leaving that last bit aside, and bringing us forward to from then to now, and the work that you’ve been doing since then. Where are you seeing the big holes in their thinking, then and now? Where are they just not seeing? Where is the materials and minerals blindness affecting Europe and then presumably affecting the rest of the world?

Simon: So the problem here is for the last 50 years we’ve used ideology to solve all our problems. If we don’t like something, we ignore it. And if we ignore, it doesn’t exist. Right. So the circular economy as it was proposed originally is the best game in town. And it’s a stepping stone or a gateway to the real thing, which I’ve now put forward as a resource balanced economy. And that may be a stepping stone, too, but but in its current form, what we call the circular economy is thermodynamically impossible. It’s just not balanced.

Manda: Tell us what it is and where the holes are in it then.

Simon: So the idea of circular economy. In the linear economy, which we like to poke fun at Australia; you know, the land of milk and honey, where they had all the opportunities in the world, but they still screwed the pooch.

Manda: Poor pooch.

Simon: Well, they did. And that’s exactly how everyone feels. Poor pooch. What were you thinking? We will get even. So what we do in Australia is we dig stuff up out of the ground, we turn it into stuff we don’t need, to impress people we don’t like, and then we throw it away and then it goes into landfill.

Manda: Yeah, well, I don’t think Australia is alone in that. Except we don’t do the digging out of the ground. But we still pay money to get stuff we don’t need, to impress people we don’t like, who don’t care, and then we throw it away.

Simon: Yeah. So actually I like making fun of Australia and I’m Australian so I can do it. So the whole premise behind the linear economy, which is how we got this far, the last couple of centuries, is we are consuming resources like locusts as fast as possible with absolutely no thought about what resources we have left, sensible land stewardship, any idea that there might come a point where there are limits. And we’re not running out of resources. Our ability to access resources is what we’re running out of. That’s the problem, right? So the circular economy was the idea that instead of actually extracting materials out of the ground, could we recycle our waste? So instead of actually dumping our waste into landfill, take that waste, recycle it, get what we need from that. And so everything that comes out of the waste goes into manufacturing. Manufacturing goes around, and you have this perfect cycle. We’re no longer mining and we’re no longer dumping waste. Okay, it’s a lovely idea. However, the stuff that we manufacture and then consume, we are not collecting to recycle. There are real problems with that. The stuff’s not designed to recycle, which means we can’t even get what we need out of it. And the energy you’ve got to put in, to actually separate everything out to their separate elements. Some things just aren’t possible. Like if you have a cup of tea on your desk in front of you. Imagine, if you will, if you wanted to separate that cup of tea into its constituent components. Like I’ve got my coffee here and it’s got milk in it. So get the coffee, separate out it into water, milk and the coffee grains and all that to the point where you can reconstitute it.

Manda: And drink it again. Yeah.

Simon: It’s chemically transformed, you actually can’t do it. So that’s the challenge a lot of the recycling actually faces. So the waste stream volumes that go around that loop, what goes into manufacturer is many times larger than what comes out of recycling at the other end. Now the existing circular economy doesn’t have an energy term of what it takes to do anything. It takes energy to move stuff around. It takes energy to do all industrial actions. They just don’t think of that.

Simon: Money is not in there either, like finance. And that’s our decision making of whether we should do something or not. And it didn’t, but now they’re starting to think about information systems, where they’re actually tracking, where information can tell us what to do. Because in recycling and the recycling world, the big challenge is how do we get the right residue into the right process plant, fast enough to make an engineering decision? And that’s the challenge. And it’s really hard. So the the circular economy in its current form won’t work, but we’re looking in the right direction. So now we need to jump to the next possible thing, that actually does look at the holes in the circular economy. And that’s the paper I have just written and proposed. And that is a proposal that needs to be pulled apart and then put back together to actually make it… I see it as an evolutionary thing, as in someone will now come back with an evolution of.

Manda: So my Evolution of it, or one question that I have, is in the conversation we’re having at the moment, we’re assuming that the businesses continue; we’re assuming that the economic system continues and that everything is predicated on making money. However, there’s a quote in your paper Civilisation is always and everywhere, a thermodynamic phenomenon. Which really struck me. And it tails with everything that you were saying, which is that we are a civilisation based on the fact that we found a whole bunch of ancient sunlight and we’re using it without thinking what we’re doing with it. And we have used as much as we can without contaminating our environment to the point where we can’t exist anymore. So at some point quite soon, it seems to me, I hope, the people who hold the reins of power are going to start needing to do the metrics with everybody, of what do we actually need? Because if I look at the stuff that I can buy online, I don’t need 90% of it to survive. Working out what I actually do need is going to be difficult and working out what we need as a culture, because I live in the middle of nowhere and what I need is very different to somebody who lives in the middle of Helsinki. But if we’re going to work out a genuinely resource-based economy, where we do design things such that the outflow of one production system flows into the next, with a minimum extra energy to create one into the other, to separate the coffee into its constituent parts. We’re going to need to work out do we need coffee in the first place? Coffee’s probably not a good example, but do we need cars? I remember hearing you at some point saying that if every vehicle in Europe was changed to be an electric vehicle tomorrow, it would take 16,000 years to mine all the lithium. Was that you who said that? And that’s not going to happen. So we need to stop thinking that that’s a thing. Are you hearing anybody beginning to ask those questions?

Simon: I am now.

Manda: Okay, good.

Simon: I put this work out in 2021. It turns out there’s a few people who have done similar work and they’ve come to similar conclusions. There is a chap called Mark Mills in the Manhattan Institute in America, who published two papers. He might have even published them a little bit before I published my work. He had a fundamentally different approach to all of this, and he came away from it (I can send you the links if you like) but he came back to the same conclusions. When we go to the green transition, what we’re actually talking about isn’t going to work and it’s just simply not possible, with thinking as it is now. But he was buried. It was very hard actually for him to get any sort of information out there. So my study was to look at what do we replace around us now and then work backwards. He looked at mining rates and what are we doing now and the energy that comes from that, and if you were to transfer it into the green transition, what would that mean? So he came to the same thing.

Simon: There’s another guy called Harald Sverdrup in Norway. He actually has evolved the Club of Rome model. He took world three, from the original 1972 model, which was actually very primitive. And he has accelerated it to modern technological capability and now it includes everything. And he can actually predict quite well, price fluctuations across all metals. And he’s got metals in there and he’s actually worked out how long will our existing resources last? So there’s now three of us. Three very different approaches, but we’re saying essentially the same thing. And we’re starting to link up and support each other. There’s another chap called Lars Shenko who wrote a book called Energy The Unpopular Truth.

Manda: I’ll put it in the show notes.

Simon: So anyway, now that politicians are saying we will now commit by 2030 to have one third of the system electric. They’re now starting to actually sort of start to look at what’s actually involved here. And the tears are starting and the screams of pain are starting. And we’re now starting to do the math. I routinely get invited into high level groups to present my work, like I’m now presenting for the fourth time to members of the Finnish parliament in a couple of months. And the Department of the Environment is on top of that, they’re trying to get their arms around what it means. So they still don’t quite know what to do about it, but they’re still processing what do we do?

Manda: Do they then feed back at international level do you think? Because I can imagine that Finland, Sweden, Norway, Denmark, Iceland, Scotland, when it gains independence, could could form quite an interesting Nordic social democratic hub. And I completely get that left and right no longer apply anymore, but there’s a license that people have in nations, which have an agreement that the Commonwealth is worth supporting. As opposed to places like the US and England, where the point is to make rich people super rich, and make sure the small boats never get here, because that’s obviously really important. Today’s last couple of headlines, I mean.

Simon: It’s a good distraction.

Manda: Yeah, of course it is. And the Beeb and the Daily Mail and all the rest of it are really happy to be screaming about small boats because it saves anybody looking anywhere else. But the BBC, similarly, every time somebody comes on to talk about what they call now ‘the climate emergency’, they’re told ahead of time, because I have friends who do this, in the green room that they must be optimistic.

Simon: Yes, I’ve heard that, too.

Manda: Optimistic means that you must say the system can continue exactly as it is, and nobody’s going to have to change any part of their lifestyle, because otherwise we’re frightening people and we’re not giving them any alternatives. And what seems to me that the work that you and these other people you’ve mentioned are doing, is opening the door to guys that’s not actually a physical possibility. Which people haven’t done before. We’ve all said we don’t think this is a good idea, but we’ve not done the ‘it can’t actually happen’. So can you throw us some of the numbers that are of the impossibilities? Copper, lithium.

Simon: So I’ve heard quite a few times now, people have actually said we really like your work because you can say the things we can’t.

Manda: Right.

Simon: Right. Because they are encouraged, very, very strictly encouraged, to be positive and not scare the horses. Now my approach is not to ask anyone’s opinion. It is essentially screw you, here are the numbers, this is what they mean. And then publish them all before they can be stopped. And so now that they’re out, now let’s discuss what it means. So what I’ve done is I assembled first of all, an audit of what did fossil fuels actually do for us in the calendar year of 2018? How much did we consume? How many cars were there and what distance did they travel? Because if they were all electric vehicles, now you’ve got to say, well, how many batteries? But then those batteries need to be charged. How often do we need to charge them? Well, they consume a certain amount of energy per 100km. More kilometres means more charging. More charging means more electricity has got to come off the grid. More electricity means we’ve now got to expand the electric grid. And so I actually did the numbers for that. And yes, it’s a very primitive calculation. Someone else looks at this and says, well, you know, we could do so much better. That was a 1000 page report, in the end. It started out as a single picture in a PowerPoint presentation. And then when I tried to write down what I meant by it…

Manda: That’s 400,000 words.

Simon: That’s about right. I think it was like 480. And they said, you can’t say this without explaining this. You can’t say that with explaining that.

Manda: Can you give us the edited highlights? Because we can’t have the 1000 pages.

Simon: Okay, so the edited highlights. I’m actually making a poster for the World Mining Congress in Australia. Okay, so the edited highlights. Baseline calculation, the global fleet of vehicles I estimated at 1.41 billion. Which is very conservative, the real number is higher in 2018. They travelled 15.9 trillion kilometres in the calendar year. So I made some assumptions with regard to what is hydrogen fuel cell and what’s an electric vehicle. All short range stuff should be electric vehicle and all long range should be hydrogen fuel cell. Why? Because the battery storage mass in an EV, like the weight of the battery, was 3.2 times the hydrogen fuel cell tank of the equivalent vehicle. So what that meant was for the same energy storage, the hydrogen fuel cell can last 3.2 times longer. Or go 3.2 times further.

Manda: For the same mass of stuff.

Simon: Right. For the same mass on the truck or the same mass on the bus. However, hydrogen is an energy carrier. You’ve got to make it and if you’re not going to use fossil fuels to make it, you’re going to use electrolysis to split water. But you need 2.5 times the electricity to make that hydrogen, compared to charging the equivalent battery. So there are definite pros and cons here now.

Manda: So it goes three times further, but it costs 2.5 times the electricity. So you still get a bit of an advantage from the hydrogen.

Simon: You do. But remember, 2.5 times the electricity telescopes into how many more power stations you’ve now got to build.

Manda: Okay. And it also assumes 100% efficiency of the hydrogen or the EV.

Simon: No, no, no, no. Every vehicle class was based on a commercially available EV or hydrogen fuel cell. And in the engineering specs, they say we require X amount of power to go 100km.

Manda: Okay, that’s handy.

Simon: Or for the hydrogen fuel cell, they say we will consume x amount of hydrogen to travel 100km and then I telescoped it forward off that.

Manda: So two more questions just before we go on, because I haven’t looked at hydrogen fuel cells. So I know that for instance, in Shetland, they’re splitting a lot of water and they have a lot of hydrogen cars in Shetland, because they have a lot of wind. And how easy is it then? Because one of the features of fossil fuels is that they’re relatively straightforward to transport, particularly oil, with a great big pipeline. And you send it from country to country. Yeah, it’s always struck me that the hydrogen car was kind of like the Hindenburg on wheels. It’s basically a bomb waiting for someone to spark it. But leaving that aside, how can we transport hydrogen? Or does it take more energy to transport it? Do you have to put it in a truck that’s using up more hydrogen than it takes to transport it?

Simon: Storage of hydrogen, transport of hydrogen, the logistics and engineering of that is actually much more complicated than transporting petroleum products. Petroleum just sits in a tank. With hydrogen, you’ve got to compress it and it wants to escape through, especially as things age. So there’s a whole lot of engineering things. And yes, it probably is more dangerous than petroleum fuel, but this is something that society will just have to come to terms with, if it actually wants industrialisation. So that’s actually one of the things that the hydrogen economy has to face. The storage of and transport of a large amount of hydrogen right across large portions of society. And we’re not ready for that.

Manda: No, especially not in a way that’s energy efficient. If you’re having to use energy to make the hydrogen and then use energy to transport the hydrogen, what is the energy return over energy invested of the hydrogen at the end of it? Is it less than one?

Simon: No, No, it is not less than one, but it’s close to one. It depends on what you include in that calculation, is the answer. It comes down to how you generate the electricity to make that hydrogen. Because wind turbines, for example, you’ve got to make the wind turbine, you’ve got to put it up. And wind turbines, like solar panels, are highly intermitant in supply. So now you need a battery buffer bank to keep things stable. And actually the bone of contention in my work is how big should that buffer be.

Manda: Because you have four weeks as your buffer, is that right?

Simon: Yeah, I had 28 days. And Princeton University in America believes we only need 5 to 7 hours. All economists are now using that number.

Manda: Do they have a lot of wind in Princeton? Is that just they look out the window and it’s always wind blowing and they don’t realise that it stops somewhere?

Simon: Uh, no.

Manda: Why then?

Simon: Magical thinking.

Manda: That’s as much as we’ve got, so that’s as much as we need? Is that the answer?

Simon: They haven’t had to do it yet. And they talk a lot of s***. That sounds disrespectful, but I’ve been taken to task by these guys and I’ve called them out, and there’s actually not a lot of numbers behind what they’re claiming. Let’s go through this: Solar power, for example, they reckon they only need 5 to 7 hours. And what drives that is supply and demand must balance to a millionth of a second. That’s the engineering that’s behind the power that comes out of your wall. It’s amazing. And we do that at the moment with the gas industry. Gas can be turned on and off, up and down, at will in any weather and it can be telescoped over a long distance. And that’s how we do it. And all nations, for example, balance their power grid by trading power between themselves. And so the wind turbines in Denmark smooth out their power grid and balance, with power from Sweden and power from Germany. Both are fossil fuels based, most of the time. So it’s highly variable. And so this is the problem: we have never had to balance a renewable power grid internally at all. That’s of any large size. So supply and demand goes up and down in a 24 hour cycle. At night we need less power, during the day we need more power. Sometimes demand exceeds supply and there’s a gap. Sometimes supply exceeds and there’s an excess. They catch the excess and they keep it for a couple of days and they put it a couple of days later when there’s a shortfall. That’s what they use for that.

Manda: How do they keep it at the moment? How do we, if we’ve got let’s say a couple of days of excess, how is it currently stored?

Simon: It’s not. These systems are so small that it just goes into the grid. And the gas industry is used to match…

Manda: Okay. So you just burn less gas for a while and and then your supply goes down. Okay.

Simon: Yeah the gas plant turns up or down. Nuclear cannot do that. Coal has difficulty doing that. Hydro you can do that a bit. Right, so watch this, though. You may notice this in Scotland. The sun in winter is not as strong as the sun in summer.

Manda: Yeah. We get snow.

Simon: Which then covers the solar panels. But the solar radiance is much, much stronger. The IEA has projected wind and solar to take 70% of the energy mix for 2050.

Manda: Winter and summer?

Simon: Everything. Everything. So now you’ve got solar taking 38% of the energy mix. So large it has to be internally balanced now and it cannot be balanced off against something else.

Manda: This is the theory of the IEA. This isn’t reality. Okay.

Simon: Yeah, this is what I’m calling out. So the amount of power in summer, you’ve got to collect the excess, keep it for 5 or 6 months or seven months and then release it slowly over the following 5 or 6 months during winter. Now go back and ask yourself, is 5 or 6 hours enough?

Manda: Yeah. How are we going to do that?

Simon: Is 28 days enough? Exactly. So the answer to this, instead of flogging ourselves to try and find more power storage, is to redesign our electronic technology that can cope with variable power and power spikes and all that. And we have a society that actually can periodically go into a period of dormancy, like over winter, the way we used to do it. We became more in tune with the seasons.

Manda: Oh I can imagine the screams of pain. People being asked to not switch on their lights after 7:00 at night. Gosh, I’m astonished that nobody’s thought about this. Are they planning to just, I don’t know, coat Saudi Arabia in solar panels or, you know, go to the equator and just make a band of solar panels that doesn’t have a winter summer? Is this somebody’s plan?

Simon: They haven’t thought it through.

Manda: Right? They just haven’t.

Simon: They just haven’t thought it through. What they do is they talk in vague platitudes. We will recycle everything. We’ll reuse everything. We’ll use everything better. We’ll do gooder, do gooder on all sectors.

Manda: Okay. Everything will miraculously be improved. In your view, if you’re going to do 28 days of storage, what kind of batteries? I was looking the other day at salt based batteries, but we could only get them from Austria and they wouldn’t send them to the UK because Brexit. So anyway, they would be very, very, very big, which is okay if you live in a farm, you know, if we have something the size of a shed that provides battery storage for the year, that’s okay. But is that a thing? Is salt really a thing?

Simon: Pumped hydro is the cheapest way to do power storage at the moment. Where you’ve got a hydroelectric plant and you’ve got a reservoir at a raised level. And during the night, you pump water up to that reservoir and during the day it comes down and you generate the power as it turns the turbine.

Manda: And what’s the energy return over energy invested for that? What’s the turnout?

Simon: Uh, it’s very low. It’s only about 30% efficient. You’re losing enormous amounts of energy going in. But it’s cheap. So the problem is, we need something like about 2100 terawatt hours of power storage in a year’s capacity. We need 65 terawatt hours of batteries for the electric vehicle fleet, we need 30 times that for stationary power storage. We cannot find enough new sites to put up hydro pump storage, to do any of that. So there are things like compressed air and flywheels and and they work and they have their place, but they’ve got engineering problems on scale up. And compressed air in particular underground can only be done in some places. Like it can’t be done just anywhere.

Manda: Because?

Simon: You’ve got to find a a cavern underground that’s geologically okay. If you if you’ve got permeable rock full of faults, you compress the air, the air leaks out.

Manda: Oh, so you don’t put a great big steel steel vat in there? You just put it into the ground.

Simon: You can put a steel vat in there, too, but that steel vat will also leak as well. It helps if you’re in impermeable rock. And also you’ve got the how big a void can be supported underground to do all that? You can do it and it does work, but good luck scaling it up to literally millions of sites across the planet.

Manda: What about splitting hydrogen, splitting water to hydrogen? Is that a way of creating storage or is that just, again, you just lose too much?

Simon: That’s another proposal. So we’ve got power we’re going to use to split hydrogen, for every 55kW we put in, you’ve got 15kW coming out.

Manda: That’s probably less than the hydro.

Simon: It’s 27% efficient. So what that means is you need a 3 to 1 build out or a 4 to 1 build out, to get that. You’ve got an economies of scale problem with it. So what it basically means, is governments of the world, like there’s a roadmap of the government in Singapore that they believed they looked at all sorts of different technologies, and they came to the conclusion that battery storage was the most sensible way to go forward. Because you can make them in any weather, you can put them in any configuration, any footprint, they can be installed very quickly, they can be moved, they’re not dependent on weather of any kind, blah, blah, blah, blah. What they are completely oblivious to, is the volume of storage they need. The quantity, sorry. They have absolutely no idea. They think it’s only going to be 5 or 6 hours of capacity.

Simon: So what you’ve got in the renewable world, people working on the battery technology have not been talking to the solar panel, wind turbine technology, in terms of if we were to do this. Because everyone depends upon fossil fuels for everything to keep working in the background. We’re all still supported by oil and gas without realising it. And that’s the problem.

Manda: Right. So we’re not using renewables to make them the infrastructure that allows more renewables.

Simon: Yeah, right.

Manda: Do you see a way forward to us doing that? I can’t remember the exact number of our 2018 power use, but it seems to me that that power use is going to have to be a lot less, or we’re going to use fossil fuels more than we can afford, that will kick us over the edge into irreversible tipping points (if you think those are a thing) before we’ve got anywhere close to producing the renewables that will provide the power to keep ourselves ticking over as we are.

Simon: So the fossil fuel systems are still omnipresent. Only about 1% of the vehicle fleet is EV, the rest is ICE. The entire maritime shipping industry, the entire aviation industry. Diesel locomotives are still, you know, quite effective at pulling freight over long distances. And renewable energy represents about 4 or 5% of the global energy pie, primary energy. So the non-fossil fuel system doesn’t exist yet, which is why we can’t recycle.

Manda: It also sounds from reading your paper, it hasn’t even been designed yet. Because you were saying that wind turbines are just put into landfill when they’re done. And I can’t believe someone designs a wind turbine that can’t be recycled.

Simon: You have to remember everything around you, like the microphone that’s in front of you, for example, has been designed for performance. It hasn’t even been designed to last very long. It’s been designed for performance. The best possible performance. And then you’re going to throw it away and buy another microphone. And the company that makes that microphone wants you to buy as many microphones as possible. They want your money. They don’t care about the fact that you want their service.

Manda: But even the people doing wind turbines, do they not think a little differently because they’re embedded in the renewables industry?

Simon: Who designs turbines? The Chinese. Do they care? No, it’s money. Give me the money. La la la la la.

Manda: Oh, Simon, we are so much more screwed than I thought.

Manda: Okay. I interrupted something quite important there. Go on. Okay. I asked you if you saw a way through. So let’s just, before we go to the way through, because I think that might be podcast three. Let’s keep going down the where the minerals blindness is. So one of the big areas of blindness is that nobody’s got their head around how much battery storage we’re going to need, if we’re going to have a not fossil fuel based, power based economy. So there are two options: one is we stop being fossil fuel based and the other is we stop being power based. But our current economy cannot function without an input, an increasing input of power. So Art Berman said the other day on Nate Hagens podcast, that we’ve consumed more oil since 1995 than all of the time before that. So we are increasing the amount of energy that we’re pouring into the system.

Simon: That’s correct. We are.

Manda: So the other thing is that we agree to contract the amount of power that we need. I struggle to see how we reach that agreement. But there are other limits. It seems to me, even if you and I go under a bus tomorrow and the economy keeps trundling on exactly as it is, and people who want to be optimistic and tell us that it’s never going to change, get their way. They’re going to hit other material roadblocks. So I remember copper seemed to be one of them. Lithium seemed to be one of them. I think possibly vanadium was one of them. There were other inputs that are just not there to keep feeding the system. Can you tell us a bit about those?

Simon: Right. So at the moment we think the future is lithium ion chemistry based batteries. So I did the actual mapping and the numbers and this is all coming out in a paper that’s published. So summed together, all the metal we need to replace all the cars, some are electric vehicles and some are hydrogen fuel cells, cars, trucks and everything. Wind turbines, solar panels will now replace oil and gas. We’re going to build some new nuclear power plants. We’re going to build some new geothermal power plants, all that stuff. And so we got two calculations. One is 28 days of buffer and one is 48 hours of buffer. There are the two references I found. I didn’t even bother with the 5 to 7 hours because that was clearly bull. So let’s take the 28 days, which I think is actually still not enough, it’s nowhere near enough to actually hit this target. So the big problem here is copper. If we’re going to electrify everything, we need a lot of copper. You can make batteries out of something else. Now you can substitute copper with aluminium in some applications, but not all. You can’t have aluminium wiring, for example, in your computer.

Manda: What is it about copper that makes it so special? Is it just it’s very malleable, very ductile and particularly good at transmitting power?

Simon: It’s the electrochemical properties of the metal. If you want the brute transmission of power over a long distance where you’re actually forcing it through, aluminium works for say things like power lines. But if you’re talking about the lightning fast interactions in a semiconductor circuit, that’s where you need copper. You could use gold in some applications and silver in some applications.

Manda: Probably don’t have as much of those.

Simon: Yeah. Well, good luck convincing the gold industry.

Manda: And we can’t use light fibres? Because to the village they put in fibre and it seems to sort of work.

Simon: That does work in some applications. But that’s the transmission of information. Are you transmitting electricity or are you transmitting information in the form of light bursts. That’s what I’m saying is there’s no one size fits all here. And this is to do a job, right. So I worked out that we actually need 4.7 billion tons of copper to replace the system that we have around us now. Global production in 2019, which is the last year before COVID pandemic supply disruptions, the last year of sensible data, we’ll see for a long time. The market was producing 24.2 million tons. So you need to hit 4.7 billion tons, we’re producing 24. So we would have to operate 195 years of production to actually hit that target, with the assumption that copper is used for other things. This is what we need in addition to what we’re doing at the moment.

Simon: Right so that’s copper. Now, lithium, we like to think that lithium batteries will be the future. Good old Elon Musk came up with the idea of making batteries without lithium. But what he does with 532 chemistry is that uses nickel, manganese and cobalt. .

Manda: So we get rid of one rare earth and…

Simon: And yeah we put pressure on others, which already have a shortfall. So let’s go through it. Lithium in the current plan, with lithium chemistries, what the IEA believes the market split will be for battery chemistries in 2050. We will need 976 million tons. Now, the global market is producing, let me get this right, 95,000 tons in 2019. That is 10,258 years of operation at current mining levels.

Simon: So the next one is nickel. We need 970 million tons of nickel. Mining production is 2.3 million tonnes, so that’s 413 years of production for nickel. And the last one is cobalt. I’ve got a whole list of these, but let’s go to cobalt. We need 225 million tonnes, but we are producing 126,000 tons. And so for Cobalt, we need to be operating at 1790 years. Oh, and the funniest one of all, and this is not funny. Sorry.

Manda: The most extreme.

Simon: Solid state batteries is going to be dominated by three chemistries, they think. One of those chemistries is germanium. Germanium is not a rare earth, but we need 4.1 million tonnes according to the energy splits that are proposed. Current global production is 143 tonnes.

Manda: So how many years is that?

Simon: 29,113 years

Manda: Simon why has nobody done this arithmetic before?

Simon: Because ideologically it has never occurred to us. And possibly I’m a little crazy, which is why it’s occurred to me, not anyone else.

Manda: But you’re making the assumption that the current level of production continues and presumably stuff gets harder to find. And as far as I know, most of these things are mined in countries that are currently war zones.

Simon: Yes, that’s right. And it gets worse. Take away fossil fuels and a lot of this stuff checks out.

Manda: Because we can’t get to it without the extra energy, The fossil fuels.

Simon: We don’t mine with wind turbines and solar panels. We mine with fossil fuels. We don’t manufacture with wind turbines and solar panels. We manufacture with fossil fuels. Right. So we’re actually getting to a point here, and the point is actually once made, cannot be unmade and tells us what has to happen next. So the obvious thing now is, well, let’s just open more mines. Easy, Right? So now let’s go to what’s called state of reserves. Now a resource is a patch of ground that’s mineralised more strongly than background mineralisation. For example, in seawater there’s lithium, but at such low trace elements that how much effort do you have to go through to get a single kilogram of lithium out of the seawater? And that’s the problem, right? A reserve is actually based on some engineering assessment that we can actually access it. It’s economic, but it’s also technology. We can only drill so deep. We can’t go below three kilometres in depth, for example.

Manda: Because it’s too hot?

Simon: Heat’s a problem down there. But if we’ve got a lot of metal on Mars, does that mean we can actually access it?

Manda: True. This is back to asteroid mining. Just because it’s floating around in an asteroid, doesn’t mean we can get to it.

Simon: There’s a very funny solution for that I heard in the BHP think tank. Anyway so we need 4.7 billion tons of copper, right. State of reserves that is actually economic at current levels, are 880 million. So the reserves we have in the ground that we know we can access is 18.6% of what we need to replace what we have around us now. So let’s take this forward. For every 1000 deposits we discover, only 1 or 2 become mines, and it takes about 15 to 20 years to take a deposit and turn it into a producing mine. For every ten producing mines, 2 or 3 will go out of business because of market conditions. So the idea that the mining industry can expand quickly or even at all, doesn’t actually honour what’s facing it. In fact, the whole commodities industry has not been understood by the economists who claim to manage it.

Manda: And that’s before we look at the environmental impacts of the mining, which presumably are pretty horrific. And if we’re wanting to actually heal the biosphere, we need to not be damaging it with whatever the run offs are of every mining output. Is that a thing?

Simon: So the people who actually run the hedge funds who are actually control this system, I call them the Muppets of Cut-throat Island. They don’t care about what you just said. They claim to, but actually they don’t.

Manda: Because all they want to do is make money. What are they going to do when the money ceases to have any value? Because it’s going to do that quite soon, if what you’re saying is right.

Simon: I believe they’ve been game theorying the coming crash and they they have a plan. They’ve already got all the money, so it’s not about money, it’s maintenance of power. They’re at the top of the food chain and on the other side of this crash, they want to stay on top of the food chain. Question: How does a small number of people keep a large number of people in place, to accept crushing food shortages and austerity measures, when it becomes apparent that the Muppets in question knew this was a problem and knew this was a problem decades ago, and did nothing to help us. So this is the purpose of the surveillance state. This is the purpose behind the World Economic Forum great reset. Behind all the nice words, what are they actually looking at? This is the purpose behind how we’ve been convinced to fight each other. And we’ve been encouraged to fight each other; while we’re doing that we’re not looking at the Muppets.

Manda: Yeah, we’re all staring at how many small boats are approaching. You know, apparently there are 100 million people set to come in small boats to Britain, which is more than the entire population of Britain. And it would take several hundred years at the current rate. But anyway, never mind. I have a question on that, because I thought about this quite a long time ago, and it struck me that if I were one of the people in power… Cory Doctorow has a brilliant line on this. Have you ever read his book, Walkaway?

Simon: No, but I’ve heard of it.

Manda: You definitely I think you would like it. I’ll ask you a question about that in a minute. Remind me. But he said one ofwhat he calls Zotta Rich says it’s all about the power. The money is just a way of keeping score.

Simon: That’s right.

Manda: But it always struck me, in that book and elsewhere, is if I had that much power, I wouldn’t bother trying to control people. I would just get rid of them. Because at that level, you know, that the population of humanity is destroying the planet. And if you want a planet to be survivable, you only need a very small number to grow the food to keep you happy. The rest are surplus to requirements and they haven’t yet. So either they’re extremely incompetent or they’re not very bright. Or both. And there’s probably a third option I haven’t thought of.

Simon: So you have to remember that these people, it helps to understand what they’re doing if you think like a psychopath. Because a lot of them are psychopaths, right? And a lot of things make sense. Now, in 1972, the Club of Rome released the Limits to Growth study, and they were panned and they were bagged and all sorts of things. But the Council on Foreign Relations at the time had a couple of meetings where they actually discussed the outcomes. Now in this, everyone looks at the base case scenario and that’s the famous one. They actually had 13 scenarios, where the first is the base case scenario. They looked at, for example, all sorts of things like what would happen if we had effective birth control or what would happen if we tripled food production, or what happens if, say, resources were doubled? You know, what happens if technology became twice as efficient, really big things. And they found a population crash happened in every single scenario. So in the base case scenario, you’ve got resources decline and then you get food production peaks and declines. And soon after that you’ve got industrial pollution peaks and declines, and then you’ve got the population peaks and declines. That peak and decline of population across all 13 scenarios could be delayed, but it could never actually be prevented.

Manda: So the question then is, can we do it in ways that are generative and decent? I remember Kate (doughnut economics) saying that she didn’t lie awake worrying about the population, because we knew how to control that, because we just needed to educate the women. And so I’m wondering, is there a way where we reduce our population by women like me simply choosing not to have kids? A cultural way.

Simon: Education of of women does correlate with population growing less. And in fact, back to good old Elon, he’s actually often come out and said that we’ve actually got a problem with population decline, as in fertility replacement rate is actually declining. Like the population of Japan is shrinking.

Manda: Like this is a bad thing?

Simon: It is if you think in terms of maintaining economic activity and technology systems. But they also think in terms of, well, this country like Japan, is going down. The West is going down. But they don’t mention India is going up, Africa is going up.

Manda: China’s got a three child policy now. Yes.

Simon: And so, they do dumb things at policy level. And, you know, a lot of the Mao stories, about what Mao proposed and did and the consequences of. The problem is everything that Musk has said is actually correct. There’s data to prove it. There’s a parallel set of issues, though. We are harvesting more stuff, resources, out of the environment than can be sustainably replaced by the environment. So how are we doing it? And so we’re over our skis in terms of what’s long term sustainable for the planet. Now back to the Council on Foreign Relations. They actually came to the conclusion, and remember, how does a rich person think? Do they think in terms of like, we’re here for the betterment of humanity and we want to make a better world, or is it something else?

Manda: Okay, it might be the something else.

Simon: The empirical evidence suggests something else. So they used to think in terms of every single one of those scenarios, resources were depleted. So they actually came to the conclusion that resources were being depleted. Human population crash could not be avoided. On the other hand, the idea of growth was actually the source of their power. So they could not shut down the growth engine without losing power. So how do they maintain power, but then stop this problem of ‘their’ resources being consumed? And so then you put those things together and they came to the conclusion that, well, what we need is a sharp reduction in population for us to get through this.

Speaker3: Oh, they did okay.

Manda: Because that’s where I get to quite fast, is why am I still alive? Because I’m clearly one of the wasted mouths. And yet I haven’t been eradicated.

Simon: No. Well, hang on. There’s the thing called the depopulation agenda. The book is called Population Control by Jim Marrs. He lays out their plans to do this. What Mars does not pick up on, is that there is indeed a problem with population. So you’ve got a problem here on multiple fronts, where they’ve taken the truth, wrapped it in a lie. Or taken a lie and wrapped it in a truth.

Manda: That happens quite often.

Simon: To actually engineer an outcome that benefits them, but not everyone else. There were alternatives. They could have done something else.

Manda: Well, of course.

Simon: So this is the source of the problem. For example, a lot of the food shortages that I believe we’ll face later this year, that we’re seeing; a lot of them didn’t have to happen.

Manda: There’s a book that I plan to read soon called The Agricultural Dilemma; How Not to Feed the World by Glenn Davis Stone, which I believe, the person who pointed me at it, told me that it highlights the ways in which the food circulation problems and even the problems of growing food are entirely false. Basically, they’re products of the market rather than being products of the actual logistics of growing food. And we have an industrial growth system, an industrial farming system, which is not what we need, but we also have a dominant narrative that tells us that without pouring chemicals on the land, we won’t be able to feed a growing world. We’re coming to the end of our time for this podcast. What we’ve got to is there are absolute material constraints, logistical constraints, of the amount of stuff that we can get and the amount of power it will take to get it. That limits how much we can mine and manufacture and make in the coming decades. We’re going to hit some of those road bumps quite soon. If I’ve understood from you, I think we’re going to hit some of them very soon. And yet I’ve heard you say that we need the environmental movement to make friends with the mining movement, or the whole green agenda is not going to happen. In the last couple of minutes, can we go over that? Or is that a topic for the next podcast?

Simon: Yes, we could. We can do that. What we are faced with is a situation where we have more problems than we thought. Now, the solution set that we have at the moment, some of them are known in our past, but we’ve rejected them. We’ve got to look at everything again. What we’re faced with is a version of Plato’s Cave. Remember the allegory of Plato’s Cave? So we believe we see reality in a certain way, but actually, it doesn’t have to be that way.

Manda: We’re just seeing the shadows on the wall. Yes.

Simon: Right. So we’ve actually got to leave the cave. That’s what we have to do. To phase out fossil fuels. Fossil fuels, whether we like it or not, are going.

Manda: And have to go quite fast.

Simon: Peak oil could well be 2018 November. Art Berman has done some excellent work to show how the gas industry is supplanting the oil industry. So what we call peak oil needs to evolve. Crude oil production is declining, and I don’t think it’s coming back.

Manda: But also, even if it’s not, if we keep chucking carbon into the atmosphere, we’re going to hit tipping points from which we can’t step back. Is that right? I mean, that’s what I’ve understood.

Simon: So I think the situation is more complex than that. And the carbon in the atmosphere is a minor issue compared to species die off, oceans acidification, land degradation. What I learned on the organic farm, and Bev, if you’re listening to this, thank you. I learned a lot from you. So Beverly Buckley, she’s written a couple of books. So there was a group of trees that had a fungus on them. One side of the orchard we put some herbicide on on it to try and sort of wipe the fungus out. We ran out of fungicide and on the other side we actually put some fertiliser to balance the soil. We come back six months later. The ones that we put the herbicide on, the fungus was still there, but it was less the trees still weren’t very healthy. They were still alive, but hanging on only just. The other side, that we just balanced the soil in, the fungicide was gone and the trees were thriving.

Manda: The fungus was gone. The fungus was gone without fungicide. No more chemicals. Actually just help the trees to develop their own immunity.

Simon: Yeah. So you can either put a lot of energy into trying to stop the problem from happening, or you can put your energy into helping the system progress to the next stage and thrive. And then the problem, whatever it is, gets wiped out.

Manda: Yes, this is the principle of regenerative agriculture. We talk about it on the podcast a lot. So yes.

Simon: But now you’ve got a scaling problem. How do you convince 8 billion people to do that and how do you put them in a position where they can do that? So the only technologies we have going forward are things like wind turbines, solar panels, geothermal. They’re the things that we actually sort of have to do at the moment. And the only way we can do that is by mining of minerals. So the green transition will happen, but it will be much smaller than we think. And it’s a stepping stone to something else, but it absolutely is necessary. So if the climate movement actually wants to get anywhere and actually have any relevance at all, they have to literally partner up with the mining industry, to the point where they’re working together and they’re not fighting each other anymore.

Manda: Does either side of that want to do this?

Simon: They’re starting to.

Manda: I can imagine me persuading my environmental friends that they need to talk to the mining industry. I struggle to imagine the Muppets of cut Throat Island wanting to talk to the environmentalists, and it seems like they’re the guys pulling the strings.

Simon: No, the Muppets are the people in charge of the money level and they are 3 or 4 degrees separated from physical reality. The people who do the mining are actually, a lot of them, are environmentalists themselves. But the environmentalists won’t talk to them. They are already there. This is a lot of deceit in current society at the moment. And bad faith, circular thinking. We have a very serious problem, where when the average person understands how much they’ve been lied to, they will get very, very angry and there will be a very natural pushback.

Manda: Let’s leave with the idea, I think, that those of us in the environmental movement, need somehow to be talking to the people on the ground in the mining industry. And working out what we actually need, how we could actually get it in ways that are not going to destroy the biosphere and will leave the Land healthier. And I’ve heard you say that it is possible to do mining and to leave behind something that was better than what we started with, or at least not as any worse.

Simon: Yeah. So what that is actually about, is they talk about zero waste mining and that’s bull. What I would like to see happen instead is what I call zero impact mining. Go out to an area, mine it. And when you finish and you do the land rehabilitation, it’s actually possible to do the rehabilitation where the plants are put back in exactly the same way. And if you do it properly, you won’t even notice there was a mine there if you were to walk over that land, say, 20 years later. And that is entirely possible. There is the technology to do that. What I’m now proposing is every time we mine, not only do we put the land back the way it was, but while we’re actually doing it, re-establish the soil food web and actually make it a biodiversity hub. And that biodiversity hub wouldn’t have existed before.

Manda: Okay, I think we’re going to carry that into the next podcast because I think that’s really exciting and I think there’s quite a lot of depth to that. But we’re so far over time on this one, let’s call it a day at that one. Thank you. And we’ll be back very soon with another one. Thank you. Simon.

Simon: Okay.

Manda: And that’s it for now. With enormous thanks to Simon. I didn’t read every single report that Simon has written because they’re about 800 pages long. Really. And you’ll find them on his website if you want to read them. And they are amazing. But his YouTubes are there, too. And I did watch quite a lot of those and read the stuff I could get my head around. And in the end, we spent four hours talking. So that was the first hour. And we concluded and then we went off and had a cup of tea and wandered around and fed the animals and shut the chickens up and all those good things. And then we came back and the second one was, I think another three hours. It was certainly a lot longer than one. So we will split the second part of this conversation. We’ll put it out in a couple of weeks time to give you time to digest this one. And also so I don’t mangle my schedule completely. And I hope and believe that it will be the first in what could be quite a long series. Because Simon is pretty much the only person that I have found who can get to grips with the bricks and mortar, in ways that look at where we’re getting the bricks and the mortar from. And then how much we’re going to need and how we might physically fit the world together in such a way that we can build the communities of place and passion and purpose that are going to see us through.

Manda: So we will be back next week with another conversation. Next week it won’t be Simon, it will be somebody else, But Simon will be in a couple of weeks time. And in the meantime, extraordinary thanks to Caro, for making the sound work and for sorting out the breakpoints in our conversation. Thanks to Faith for the website and the conversations that keep me and us moving forward. To Anne Thomas, for the transcripts. And as always to you for listening. We wouldn’t be here without you and we are weakly grateful that you are there. And because I still believe that word of mouth is by far the best way we are going to change the world, if you know of anybody else who would like to get to grips with some of the logistics of what’s going on, then please do send them this link. And that’s it for now. See you next week. Thank you and goodbye.

You may also like these recent podcasts

Falling in Love with the Future – with author, musician, podcaster and futurenaut, Rob Hopkins

We need all 8 billion of us to Fall in Love with a Future we’d be proud to leave to the generations that come after us. So how do we do it?

ReWilding our Water: From Rain to River to Sewer and back with Tim Smedley, author of The Last Drop

How close are we to the edge of Zero Day when no water comes out of the taps? Scarily close. But Tim Smedley has a whole host of ways we can restore our water cycles.

This is how we build the future: Teaching Regenerative Economics at all levels with Jennifer Brandsberg-Engelmann

How do we let go of the sense of scarcity, separation and powerlessness that defines the ways we live, care and do business together? How can we best equip our young people for the world that is coming – which is so, so different from the future we grew up believing was possible?

Brilliant Minds: BONUS podcast with Kate Raworth, Indy Johar & James Lock at the Festival of Debate

We are honoured to bring to Accidental Gods, a recording of three of our generation’s leading thinkers in conversation at the Festival of Debate in Sheffield, hosted by Opus.

This is an unflinching conversation, but it’s absolutely at the cutting edge of imagineering: this lays out where we’re at and what we need to do, but it also gives us roadmaps to get there: It’s genuinely Thrutopian, not only in the ideas as laid out, but the emotional literacy of the approach to the wicked problems of our time.

Now we have to make it happen.

STAY IN TOUCH

For a regular supply of ideas about humanity's next evolutionary step, insights into the thinking behind some of the podcasts, early updates on the guests we'll be having on the show - AND a free Water visualisation that will guide you through a deep immersion in water connection...sign up here.

(NB: This is a free newsletter - it's not joining up to the Membership! That's a nice, subtle pink button on the 'Join Us' page...)