#201 Transforming Narrative Waters with Ruth Taylor of the Common Cause Foundation

How do we change the stories we tell ourselves and each other about ourselves and each other – and our place in the world – into stories of transformation, trust and togetherness?

Here at Accidental Gods, we are increasingly of the opinion that our most urgent need as we face the polycrisis is to find a sense of being a belonging that changes our life’s purpose. We all know we’re not here just to pay bills and die, but knowing what we’re not here for is not enough: we need to feel at the deepest level what we are here for, to rebuild the deep heart connections to the web of life such that we can take our place in the web with integrity and authenticity and a true sense of coming home.

As we head into our sixteenth season, our third century of episodes, this is our baseline. The membership is here to delve deep into the practice and to give the time and the space to building the connections and the podcast exists to outline the theory and to give a voice to other people on this path.

And with that in mind, it is my great pleasure to introduce you to this week’s guest, the narrative strategist, Ruth Taylor. I came across Ruth when she published a Medium post entitled ‘To UnPathed Waters and Undreamed Shores’ – and just that title alone was enough to get me to read it. And then I was blown away by the ideas Ruth put forward, by her theories of narrative change, which are clearly at the heart of all we do, and by the clarity of her thinking and writing. I’ve put the link in the show notes so you can read it for yourself. In the 6 months since she agreed to come onto the podcast, she’s published several other posts and a long paper called Transforming Narrative Waters, which delves even more deeply into the need for, and practice of, narrative change.

Ruth works for the Common Cause Foundation which I first came across when I was at Schumacher College and had my eyes opened to the emotional intelligence behind it, and the astonishing work it’s been doing in the world. Ruth is particularly interested in narrative change and writes a regular newsletter called In Other Words that collates the latest thinking in this field so she was an ideal person to explore the nature of framing, and story and how we can get to grips with changing the stories we tell ourselves about who we are and why we’re here and how our relationships to each other and the world can still shift us away from the cliff’s edge.

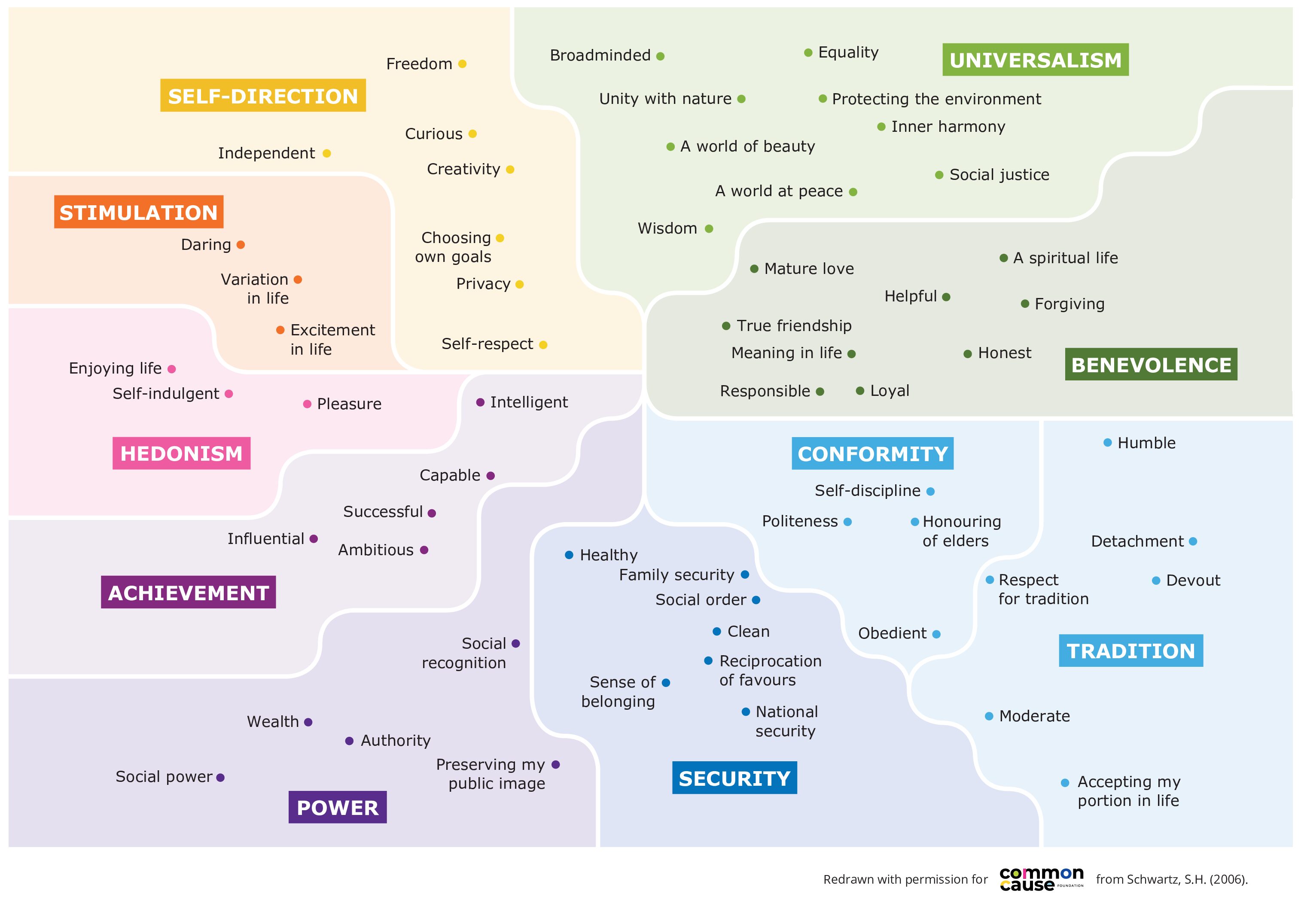

CCF is a not for profit that works at the intersection between culture change and social psychology. Over the past ten years, it has pioneered a new way of inspiring engagement through catalysing action that strengthens and celebrates the human values that underpin the public’s care for social and environmental causes. Its work is centered on the research findings that, 1) people are more likely to support environmental and social change when they place importance on their intrinsic values, such as equality, curiosity, broadmindedness and community, and 2) that the majority of people in the UK place importance on these values, but are constantly having their more extrinsic values primed due to the consumerist culture in which we live. With this in mind CCF offers training and support to a range of organisations on how to develop messaging and campaigning strategies that engage with people’s intrinsic values in order to rebalance the value norms in our societies.

Episode #201

Links

Ruth on Linked In

To Unpathed Waters and Undreamed Shores

Transforming Narrative Waters

Culture and Deep Narratives blog (Medium)

Online Course: Values 101: Creating the Cultural Conditions for Change

Global Action Plan

Internarratives

The Common Cause Foundation

HumanKind Book

CultureHack

Narrative Initiative

The Culture Group

Parents for Future

In Conversation

Manda: Hey people, welcome to Accidental Gods. To the podcast where we believe that another world is still possible and that if we all work together, there is time to create the future that we would be proud to leave to the generations that come after us. I’m Manda Scott, your host in this journey into possibility. And I am increasingly of the opinion that our most urgent need as we face the crisis is to find a sense of being and belonging that changes our life’s purpose. We all know we’re not here just to pay bills and die. But knowing what we’re not here for is not enough. We need to feel at the deepest level what we are here for. To rebuild the deep heart connections to the web of life, such that we can take our place in the web with integrity and authenticity and a true sense of coming home. So as we head into our 16th season, into our third century of episodes, this remains our baseline at Accidental Gods. The membership is here to help us all delve deep into the practice and to give us the time and the space and the means to build the connections that really matter. And then the podcast is here to outline the theory and to give a voice to other people on this path. And with that in mind, it’s my great pleasure to introduce you to this week’s guest, the narrative strategist Ruth Taylor. I came across Ruth when she published a medium post entitled To Unpathed Waters and Undreamed Shores. And just that title alone was enough to get me to read it and then I was blown away by the ideas Ruth put forward. By her theories of narrative change, which are so clearly at the heart of all we need to do and by the clarity of her thinking and writing.

Manda: I have put a link in the show notes so you can read it for yourself along with everything else that Ruth has written in the last six months, since we first booked her to come on to the podcast. She has published several other blog posts on Medium and a long paper called Transforming Narrative Waters, which delves even more deeply into the need for and the practice of narrative change. Ruth works for the Common Cause Foundation, which I first came across when I was at Schumacher College and had my eyes opened to the emotional intelligence behind it and the astonishing work that it’s been doing in the world, which we go into in a bit of depth at the beginning of the podcast. Ruth is particularly interested in narrative change and writes a regular newsletter called In Other Words, that collates the latest thinking in this field. So she was an ideal person to explore the nature of frames and framing and story and narrative and how we can get to grips with changing the stories we tell ourselves, about who we are and why we’re here, and how our relationships to each other and the world can still shift us away from the cliff’s edge. And that’s what we’re here for. So people of the podcast, please welcome Ruth Taylor of the Common Cause Foundation.

Manda: Ruth, welcome to the Accidental Gods podcast. It is a delight to talk to you at last, because we’ve been planning this for at least six months I think. How are you and where are you this morning?

Ruth: It’s lovely to be here. I’m really well. I am currently in my office slash spare bedroom at home in Hither Green, Southeast London. The sun is shining and yeah, things are good.

Manda: You have sun. Okay, I have sun envy because it’s rained here solidly since we got the hay in a week ago Sunday. So I’m not complaining, because we did get some hay, which I thought was not going to happen. So life is good and you work part time for the Common Cause Foundation. And of the highlights of the Schumacher year that I did, one was Kate Raworth, one was Rob Hopkins. There were a couple of others, but Tom Crompton coming to talk to us about the Common Cause Foundation, about which I had very shamefully never heard before; what it did, how it worked. Particularly the ideas of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation was a light bulb that went on and has stayed on ever since. So can you tell us a little bit about what the Common Cause Foundation is and your interaction with it and then we’ll move on from there?

Ruth: Sure. Yeah. And I’m so happy to hear that it’s stayed with you. I’m biased, but I believe it’s revolutionary. The kind of concepts that we advocate for. So, Common Cause Foundation. I would imagine a lot of people haven’t heard of us. We’re only three people. We’re very tiny. Common Cause started life as a report actually, back in 2010, I believe. At that time Tom Crompton was working at WWF at the time, and he’s very inquisitive, naturally. And he started reflecting, I suppose, on the change approaches that we so often see in large organisations like WWF. And maybe sort of looking at the scale of the challenges that we face globally and then looking at the approaches that we so often employ, and feeling like maybe the two don’t add up. How are these small incremental steps going to add up to the scale and the depth of transformation that we that we really need? And he became really interested in the field of social psychology and developed a number of relationships with different social psychologists, academics across the world. And from there I suppose lent in to exploring how this body of academic literature, that looks at human values, so our deepest motivations, the principles that really guide how we live our lives. How those could be utilised within the world of social and environmental change making. So initially it was a report that came out, kind of co-authored by WWF, Oxfam, a couple of other large NGOs. And from there it sort of built momentum, I suppose.

Ruth: So it established as a separate organisation from WWF in 2015 and we’ve been going ever since. I guess when it first started it had a focus really on values and what was then a fairly new idea around framing. So how do we frame our messages in certain ways to engage to prime particular values. And, and at that time, framing was a fairly new idea here in the UK and was building momentum. Nowadays we’ve taken a bit of a shift, I suppose, in focus. Strategic communications framing is really important and it has its place and you know, it’s brilliant that so many organisations now see that as a really fundamental tool within their kind of comms work. I suppose for us we’re now really interested in how do you create the cultural environment, how do you create the kind of cultural surround, to where when that frame is released into the world, it really embeds. It really is effective. The demand is there to see this sort of frame. So it’s really now more into a space, I think, about culture change. How do we create the kind of cultural soil around us to make the situation such that we are ready for the kind of large scale changes that we need to see, in conjunction with the kind of poly crisis that we’re we’re living through.

Manda: Brilliant.

Ruth: And for me personally, I’ve been at Common Cause for about three and a half years now. My background is in campaigning and organising, and I’ve always worked in the sort of social justice sector. But I guess very early on in my career, I felt a deep frustration for the way that we were working. And I found it very difficult to articulate that for quite a long time. You know, I was looking around and thinking, is it just me that feels like this? This sense of I can ask people in the most effective ways to sign this petition and I can encourage them to reach out to their MPs and I can do all of that. Is this going to stop climate change? Is this going to eradicate mass inequality in our world? For me, it really didn’t feel like things were adding up and I got really frustrated. So I spent a long time trying to search for a kind of explanation for why I had this feeling of frustration. And it led me to the work of Common Cause, the work of the Public Interest Research Centre, Ella Saltmarsh. Lots of people that have done lots of thinking and writing on this topic. And finally it gave me a language to explain that feeling of frustration, and it made me excited that there are people who are thinking that actually we really need much bolder, much more courageous approaches to change. So after a number of years of freelancing, a role came up at Common Cause and I jumped at it. And luckily for me, got the role there and have been there ever since. And it continues to inform my kind of worldview, I suppose. Definitely how I think change is going to come about.

Manda: Brilliant. There is so much in there to unpack. Let’s take a step back and talk about framing. Because I understand that in your world, framing is now something that is a given. But my experience is in the outside world, most people still don’t know what framing is, in spite of the fact that they live within frames. So can you just unpick for us what a frame is and then the ways that people can embed it? You talked about strategic communications framing, so let’s go from framing to what is strategic communications framing.

Ruth: Sure. So framing is a practice that’s been developed from cognitive linguistics and social science. So thinking about how we place meaning on certain phrases, certain words, etcetera. So as human beings, we are bombarded by content all the time and our brain has to find shortcuts, ways to help us to process this kind of information quickly. And what framing is about is about identifying those kind of shortcuts and trying to… Manipulate them makes it sound really devious. I suppose support people to replace associations in their brain so that their associations are more positive, more sort of pro-social or pro-environmental. So in terms of framing, if I often think it’s easiest to give an example. So if I said to you, my new job is like being on holiday, you know exactly what I’m referring to. I’m referring to my new job being really enjoyable. Maybe it’s quite peaceful, etcetera. All of these things come to mind for you. And I’ve just used the frame of a holiday and all of the cultural associations we have with that. But if I said, Oh, my job is like going to school, you’d have a totally different understanding.

Ruth: It doesn’t require me as the person who’s talking to you to give you all of that information. I don’t have to explain it all. I’m depending on the frame that you already have in your brain of school or a holiday, and you then colour that in yourself. So it’s the same when we’re talking about social environmental change and we say climate change is like a war, or climate change is this natural beast that we’re fighting or something. We’re bringing to mind different associations. And some of those are helpful for us in terms of bringing people to agreeing on more pro-social or pro-environmental policies. And some of them are not helpful. So framing is the process of trying to unpick that, to identify positive frames, to identify negative frames and then replace them with more positive framing. And it’s a fundamental part of social environmental change work that I think is hugely important and all organisations should be doing it. Comms isn’t just a function of our work, it’s also fundamental to the changes that we make.

Manda: So we’ve talked about language and that it’s perhaps not helpful to look at everything in terms of a zero sum war and that if we if we use militaristic language, we set people up for a particular way. It seems to me that framing can be unpicked a long way down into the depths of our amygdalas in a way. I’m not going to argue with you, but I’m aware that there are people listening for whom talking about the limbic system or the amygdala is kind of a huge trigger, because the neurophysiology is a lot more complicated than that. So guys, we’re going for neurophysiology 101, where we’re using the amygdala as a metaphor for our limbic systems and the bits that are way down deep and not really accessible by our consciousness. Let’s clear that one out of the way. And that framing, generally speaking, hits into the parts that think very fast, as opposed to the cognitive parts that think very slow, if we look at Daniel Kahneman’s metaphors. It has always seemed to me that the populist side of the political spectrum, and particularly the right populist side, is very, very good at using very swift metaphors. Visual ones and linguistic ones, to get a message that hits people in their gut. And that we on the progressive side, however we try and frame it, have a tendency to explain things that go straight to people’s cognitive balance and are completely ignored because they’ve already made a gut level decision. Is it the case that people wanting to create pro-social change, wanting to find flourishing ways to address the poly crisis, are beginning to understand that we need to go in at gut level? Is that something that’s becoming more of a thing? And if so, how? How are we doing this? Because I’m not seeing it happen in the outside world.

Ruth: I think that that penny is starting to drop, definitely. With the rise of framing as a practice, there comes this belief and this idea that we’re not rational creatures. As much as we like to think we are and as much as science over the last hundred years has told us, you know, we’re the sort of creatures that have all of the facts and then we make a rational decision about whether to act or not act, or what to believe or what not to believe. It turns out that that’s really not true. We’re much more emotive than we are rational. And we go with gut feeling a lot. We go with our emotions; what makes us feel good, what makes us feel scared. And I suppose there is a realisation that that’s true. It’s definitely not happening everywhere. I don’t think all organisations or all social and environmental movements are working from this premise. We’re still falling back a lot on this idea that if people only knew the scale of challenges, then they would be forced to act. And that’s just really not true.

Manda: It’s so obviously not true.

Ruth: Exactly. We know things are terrible. Yeah.

Manda: Yeah. And the definition of insanity is doing the same thing time after time and expecting a different result. And we’ve been explaining how bad things are since the 80s.

Ruth: Yeah, exactly.

Manda: And it’s only getting worse.

Ruth: People often use the example of smoking. You know, we know smoking is bad. We know smoking is bad for you. And yet people were doing it for decades and decades and decades. We are seeing a change now. But just because we know that a situation is bad doesn’t necessarily mean that we are going to do what needs to be done to change that situation. There is much more that has to happen, almost at heart level, for that to be the case. We’re seeing a rise in talk of narrative and narrative change now, which I think taps into this more. It’s getting out of people’s heads. They don’t just need the facts, they don’t need the figures, they don’t need the stats. They need something much deeper that talks to them on a much more human level. And that really excites me. That we’re starting to see this shift, we’re starting to see more appetite for that way of working. Which for me is just so uplifting and exciting, the possibilities that could lay ahead of us from working in that different way.

Manda: And that’s where I would like to go next. But I want to take a step back before we go there and look at intrinsic and extrinsic values, because I think that helps people to ground frames. I just I had a little anecdote that I wanted to share, because Tom came and taught us at Schumacher. And then for the next couple of years after we had the elective, that was also a short course, a three week course that people could come to. And I think 2019, so two years after Tom was with us, I taught the framing section. And there was a really charming student who was definitely at the older end of the range, who took me aside after I explained the the limbic nature of how we make decisions. And he was from the north of Scotland and he said, But you have to understand, we are rational beings. If that’s not the case, everything will fall apart. And he was so obviously hugely limbically triggered by this. He was terrified by the idea that we might not be rational beings. And I hadn’t come across that as a thing. And we had a very interesting discussion and it was fascinating to watch. And I think one of the frames that we have to counter is the idea that we are rational beings, and that if we’re not the whole world, you know, the horror of the primal underlay of who we are will kind of rear up and swamp us.

Manda: And those are the kinds of language that I notice being applied to migrants. Is swarms and swamps and everything that seems to sink into our fear of everything that is actually connected to the earth. And I want to unpick a little bit more about framing, because I came to it first through George Lakoff’s book, Don’t Think of an Elephant. And he talked about the frames of the strict father frame and the nurturing parent frame as being the two that he saw. And he was largely looking at a highly divided American culture, where the strict father frame is so embedded in at least 50% of the population that anything that speaks to that is taken up, and anything that suggests anything else simply isn’t heard. So Jonathan Haidt said in his book The Righteous Mind that MRI studies and things, if you talk to somebody outside their frame, it’s not that they’re deliberately ignoring you, it’s that they actually don’t hear what you’re saying. And that seemed to me a really important and fundamental concept that we need to address somehow, given where we’re at in the poly crisis, given the urgency of the moment. If people actually cannot hear us, then how do we find a frame whereby we can begin to open their capacity to hear? And the same applies to an extent in the nurturing parent side. So one of the things that struck me that could reach that, was the understanding of intrinsic and extrinsic values that the Common Cause Foundation had brought to light. Can you talk a little bit to that?

Ruth: Yeah, absolutely. Let’s start with all values. All values very deep rooted sort of principles and motivations that all of us have as human beings, that we reach for when we’re trying to make decisions. So they inform our attitudes, our behaviours and the way that we think. Some of these values that we hold are what we might call dispositional values. So they’re values that are really, really important to us because of our upbringing, how we’ve been educated, our faith if we have one, the political context we’ve been brought up in, etcetera. And but a whole range of other values are what psychologists might call primable for us. They can be engaged. So I would say that I’m probably someone who dispositionally holds what psychologists might call universal or benevolent values. I place a lot of priority on things like social justice, equality, my love for my friends and my family, creativity, protecting the environment, things like that. That has directed a lot of my life choices and how I live my life. Those are maybe dispositional values for me. But other values are equally as primable. So I went to the cinema the other day, sat down, watched an advert on the latest iPhone and immediately I’m like, I need the latest iPhone.

Ruth: You know, you’re a creature like any other. Values are primable for you. So a value of wealth or a value of success, a value of achievement, these values are held within me as well. I jump around depending on what’s going on, the messages I’m receiving. So intrinsic and extrinsic values are sort of subcategories of values. We’re particularly interested in these two groups because there is just a ton of research that talks about the tensions between these two groups, and also that when somebody is able to draw on intrinsic values to help them make decisions, they are more likely to be supportive of pro-social and pro-environmental action. So these two groups, they sort of exist in tension. So on the one hand, with intrinsic values, they are things like quality and creativity, freedom, our love for our communities, our love for the more than human world and our feelings of solidarity with others, etcetera. And extrinsic values are values which depend on how others see us. So they are about things like wealth or status, public recognition, how intelligent we are perceived to be, things like that.

Ruth: And it’s not to say that extrinsic values are bad. They’re not. We need them as human beings to survive and to function. But what we at Common Cause talk about is how culturally these two groups of values are out of balance. Culturally, we receive so many messages that tell us that we need to prioritise extrinsic values. And because we know that these two groups of values act in tension, we talk about them as being on a seesaw. When we engage extrinsic values, we disengage our intrinsic ones and vice versa. So if you think about it, so often our attention is being drawn to our extrinsic values, which means our attention is being pulled away from our intrinsic ones, which are the ones that we need to see greater public demand for social and environmental change. So for me, yes, organisations need to think about how they frame their issues differently, but it goes deeper than that. We need to think about how we as organisations that play a role in shaping the broader cultures that we’re in, how we lay the groundwork so that certain frames are more attractive to people than other frames.

Ruth: So I am a visual thinker. So when I think about this, I often think about planting a seed. If you think about a campaign or a comms initiative, some work that a social or an environmental organisation is doing, if you think about that as being a seed, you could create the best campaign that you could, that has all of the best practice pumped in it. It’s got the best frames possible. It’s utilising the best comms channels, the best messengers, etcetera. If that seed is landing onto soil, which is arid, is not able to help it to seed and to grow, it’s not going to work. So there’s a sense that, yes, we need to have that brilliant seed, we need to have the best framed campaigns we can, etcetera. But our work also needs to nourish the soil. It needs to help to create the cultural conditions where that campaign is going to land and flourish, where that seed is going to, you know, embed and be able to germinate. So we ask a lot, I think of organisations. We’re asking them to think as well about the cultural impacts of their work, not just the frames that they are utilising. And I think that comes back down to the values that we’re drawing on a lot of the time.

Manda: Brilliant. So, yes, one of the things that really struck me was the understanding that if we can tap into someone’s intrinsic values, their awareness of dependence on self scoring on extrinsic values goes down. Whereas when the entirety of the advertising system, the media ecosystem, completely continues to hit onto their extrinsic values, it’s very difficult then for people to access their intrinsic values. Again, while I was at Schumacher, a friend really brought this home. At Schumacher nobody wore make up. Nobody wore high heels and fancy clothes. You’re working in the gardens half the time. You wear whatever’s comfortable and you’re valued for who you are. And my friend had to go to London for a bit and was walking down Oxford Street. And she said by the time she’d taken about half a dozen paces, she was aware of the fact that she wasn’t wearing makeup and she was just basically wearing trainers and jeans and wanting to smarten up and look different and look how the extrinsically valued world wanted her to look. And was feeling that seesaw happen inside her. And that again, made a huge impact on me. Tom told us about a study that was done at the museum in Manchester or somewhere in Manchester, I can’t remember exactly where. But where there was a deliberate attempt to connect to people’s intrinsic values. And it seemed to me a really good exemplar of how we could go about doing this. Can you speak to that a little bit?

Ruth: Yeah, absolutely. So this is a really exciting project. Before my time unfortunately at Common Cause, but it’s one that we talk about often and we continue to work with museums today, so it’s still really alive in what we do. I guess it draws on this idea that social and environmental organisations, those with specific remits to be trying to bring about a more just regenerative world; they are not the sole owners of that mission. So our work today works with lots of organisations that we call culture makers. So really that draws on the idea that there are so many different types of sectors, different fields that play a part in creating the cultural values that we have as societies. NGOs are definitely one cultural actor, but there are lots of others. So one of those we thought might be museums. And there’s lots of work that happened in museums already about how do they reduce their carbon footprint? How do they ensure that they are really inclusive, accessible spaces for a really diverse range of people? All of that work really, really powerful and important. I guess we came in with a question of what’s your cultural values footprint? Not your carbon footprint. What values are you reinforcing and strengthening culturally in the people that walk through your doors every day? So Manchester Museum, part of the University of Manchester, were really keen on this idea. And we got some funding, interestingly, from an environmental funder, even though this project was nothing to do with the environment kind of tangibly, but it has an impact in that if we’re strengthening intrinsic values, we’re strengthening the likelihood that someone is going to engage with environmental policies and be in support of environmental change.

Ruth: So the project was about exploring ways that Manchester Museum currently engage different values. They could be intrinsic already, or could be extrinsic. And then to think very intentionally about ways that they could engage intrinsic values in their audiences. So there were a number of interventions, some of them very small. So there’s a volunteer handbook that Manchester Museum has. They have hundreds of volunteers that work for them every week, many of them motivated by intrinsic values, by wanting to offer experiences to people, to feed their curiosity, to connect with those that they might not normally connect with. But if you were if you were a visitor to Manchester Museum, it’s very unlikely that you would know anything about those volunteers and their motivations. So we wanted to bring that to life. And so we had little badges printed that said I’m a volunteer, talk to me about why I volunteer. We changed the volunteer handbook so that part of the volunteer commitment was to speak really openly and honestly about those intrinsic motivations, bringing them to life for other people. We had posters up around the museum both inside and outside, that introduced visitors to some of the volunteers and the reasons why they do what they do.

Ruth: And we had moments for visitors to connect with each other. So they had a day every month that was a big push to get more visitors through the door one Saturday every month. And we created a space where people were invited to come and sit on sofas and speak to strangers about what they really cared about. What they loved about Manchester, what made them really happy as human beings, etcetera. And we had a kind of graphic artist doing a drawing relay, being able to kind of capture these things visually. And it was a way of trying to support people to have conversations about things that are a bit deeper than the weather, or looking at the bus timetable or something. But to connect with people that you wouldn’t necessarily normally chat to and then be able to be like, amazing, we’ve got so much in common. We hold some of these really deep intrinsic values to be important.

Ruth: And that that goes on to a whole other area of research about how we perceive the values of others and the ways that that impacts our own actions and our own beliefs, etcetera. But yeah, it was an amazing project and it’s been replicated in a couple of other museums now and we’d love to see it happen in other sorts of spaces, other spaces where we gather. You know, libraries, theatres, event spaces, you know, the opportunities are endless really.

Manda: So much I could ask about that. Do you want to get on to narrative change? But some quick fire questions on that. When you said it’s been replicated, has it been replicated in other cultures? Because it seems to me that in Britain and actually particularly in England, not as much in the Celtic nations, there is a reticence around talking about how you feel. And I wonder, would it be different in a South American country or anywhere else where the social constraints are different? So that would be question one. I’ll fire a few at you. Really interested in the perceived values of others, because in one of your papers I read particularly that young people thought that they were really concerned about the climate but that their peers were not. And that changed how they talked about it. And I think that is a huge area that we could look at. So let’s have a quick look at that. And then very briefly, because this is my obsession and probably doesn’t apply to anybody else, but I’m still really curious. We have intrinsic and extrinsic values. And I’ve been reading quite a lot recently about neurotransmitters, particularly when we’re talking about oxytocin, which we used to think would make everybody happy and generous and intrinsically motivated. And actually what it does is make us happy and generous and intrinsically motivated to the people we perceive as our tribe. And we become really nasty to the people we don’t perceive as our tribe, so it increases our tendency to ‘other’ other people. And I am really curious to know if there’s been any work done on the neurotransmitters of intrinsic and extrinsic values. So there’s a whole bunch of questions there. Pick what you can answer and let’s go with it.

Ruth: So your first question about replicability and is this something that we’ve seen happen in other countries? So we’re a UK based organisation. We do work with partners across the world. And we’re doing more work increasingly with people that aren’t in an English speaking nation, but we haven’t ourselves done museum work directly in other countries. We do know of a project that’s called the Museum of Values, which is happening in Germany that is super interesting and I definitely encourage listeners to go and look at that, because it’s really cool. We ourselves haven’t done that and I agree that there is something very British or very English about not wanting to share too much. But you do see research come out every now and again about this real desire that people have to have conversations with people, about things that are a little bit more important to them. And we found with the Manchester Museum work that a lot of the feedback was, you know, it was so great to talk about something that’s really important to me and to hear that other people also think that that’s really important. And so I found that really encouraging.

Ruth: And it’s a good prompt when I’m chatting with a stranger to to not shy away from talking about stuff that’s maybe a bit deeper and a bit more meaningful than to just revert to the football or what the weather’s doing or whatever. In terms of the perception gap research, so this is our body of research that looks at the way that we perceive others, and you mentioned a study that looks at how young people understand their peers. So that was a bit of research that was done by an organisation called Global Action Plan, who took our perception gap research with adults and applied it to young people. And it’s a fantastic bit of research. So we were really interested in understanding does our perception of the values that other people have, does that change how we then ourselves act? And we’ve done this research both in the UK and the US, but it’s a really growing field of study. So we’re seeing lots of different psychology labs across the world now taking up this research question. So we’re getting data now on lots and lots of different countries, which is brilliant to see.

Ruth: So what we found is that people perceive themselves as holding intrinsic values to be very, very important. And most people, about 74% of people in the UK, prioritise intrinsic values. But we tend to believe that others prioritise extrinsic values to a greater extent than they actually do. So it’s this kind of dynamic where it’s like, well I believe in equality, it’s really important to me, but everyone else, they’re just really motivated by money and greed and self-interest. And what that does is, is it feeds, possibly, you know, this is a conjecture at this point, but it feeds into this potential kind of self-fulfilling prophecy. Whereby I look around me and I think, well, everyone is so self motivated, so what’s the point in me recycling and what’s the point in me doing X, Y, Z? No one else is bothering. And of course, my reluctance to engage in that activity feeds other people’s sense of like, well, everybody else is just so selfish, etcetera, etcetera. And we go round and round. And of course that happens at a behavioural level, individual private sphere behaviour, but it also happens at an institutional level. So if I’m someone, let’s say I’m a civil servant and I’m designing our social security programmes for the UK. If I believe that everyone’s really self motivated, really self-interested, I’m going to design a program that’s about catching benefit fraud and all of these sorts of techniques. Which means that if you’re somebody who is then engaging with that as a process, as a system, you’re going to be being tacitly reminded constantly that people are really self motivated and so it strengthens this misperception.

Ruth: So for us, a lot of our work is about trying to do what we call ‘narrowing the perception gap’. Trying to ensure that people can have a more accurate understanding of their fellow citizens so that you are yourself in a better position to act in alignment with that knowledge. But that we are actually designing our world in a way that is more reflective of human nature. And there’s other work that’s being done on this. Often when I talk about this, someone mentions Rutger Bregman’s book on Humankind. So we are starting to see more discussion perhaps, about who we are as people, what type of values we hold to be important. And I fundamentally believe that if we knew that actually the vast majority of people do place importance on intrinsic values, we would design a fundamentally different world.

Manda: Yes. And yet our media ecosystem is really busy emphasising the opposite of that. I want to get on to narrative very shortly, but I have two questions. Back to the Manchester study or similar studies. How long does that impact last? People really enjoy the intrinsicality of it and their intrinsic motivations are ramped up, compared to their extrinsic. What’s the spill-over in terms of time? That would be question one. And and just as an observation, if 74% of the population believes themselves to be intrinsically motivated, I have always wondered – at the moment we have a Tory government that was elected by 23% of the total electorate, not 23% of those who voted because a lot of people don’t bother to vote, but 23% of the total electorate got in a government with an 80 seat majority. And that matches very closely, because if you’re right that 74% are intrinsically motivated, then 26% are not. And actually that’s a rounding error of where we’re at. And so we absolutely have a political system that is emphasising the extrinsic motivations and completely suppressing the intrinsic motivations, which I would suggest is not an accident. Let’s go into designing the world in a second. But let’s first see what the longevity is of aiding peoples intrinsic motivations.

Ruth: I just want to talk about the political kind of makeup first, and then I’ll go back to that Manchester Museum Point. So values are not the same as attitudes. We know that people can hold intrinsic values to be important across demographics, and this is reflected in the data. So people are equally as likely to be a right wing voter, left wing voter and hold intrinsic values to be important. Where someone feels that they are on the left of our political spectrum, that always feels a little bit uncomfortable, because you kind of want to believe that, those who vote differently to you are somehow just holding really different values and there’s this huge gulf between you. And that doesn’t seem to be the case. So someone can really place the priority on an intrinsic value of equality, for example, and vote conservative, because they believe that those policies, those processes are what leads us to equality. So, you know, it’s the whole trickle down economic sort of framework.

Ruth: So I suppose for us, there’s a sense that values are not the panacea, they aren’t the thing that are necessarily going to mean that we’re all voting in the same way. I feel that there’s an opportunity whereby the more you speak from a position of values, the more you’re able to have a productive dialogue across political divide. So instead of it just being like, well, you’re evil or you’re stupid, which often seems to be the conversation across right and left, there’s opportunities to be like: you value equality, I value equality; here’s why I think these policies and this process is the way to get to equality. Let me hear why you think that this alternative route is the way to get there. I think it leads to more kind of ripe conversation. It doesn’t mean that everybody’s going to be voting in the same way. It would be a simple task if that was the case. And in terms of of spill-over in terms of time, this is really difficult to answer. If you imagine that you are a visitor to Manchester Museum, you walk through the doors, you’re having these experiences that are engaging your intrinsic values. You then walk out of Manchester Museum, back onto the High Street and you’re bombarded with advertising. Then maybe you need to go to your job which requires you to be really extrinsically motivated, etcetera, etcetera.

Ruth: And it’s difficult to know exactly how long that activation, for want of a better word, kind of lasts. But we do know that values, we talk of them as sort of acting like muscles. So the more that they’re engaged, the stronger they become. So the idea around cultural values change is about making sure that as many places that people are living their lives are strengthening their intrinsic values as best as possible. So yeah what does it look like for you, in your your place of worship, to have your intrinsic values strengthened? What does it look like for you at school or university or work? What does it look like for you on public transport? Or walking down the high street or in places where people gather, like museums. So that’s what we need. We need all these different actors to start having this discussion. And if you care about social environmental change, which so many people that make up these institutions do, this is the kind of work that you can be doing to really be making a deep kind of cultural level change. And the more that we’re seeing that, the stronger these values are going to be becoming culturally for people. And that’s ultimately what we need.

Manda: Brilliant. There is so much to that I would like to unpick. And particularly the idea that art would make a huge difference to how we are able to access our own intrinsic values, because it goes in beneath the level of cognitive thought. I’m thinking of Banksy particularly, but a lot of the street art that we see would really help us to engage our intrinsic values. And if we were able to completely get rid of advertising, that too would make a huge difference. But I want to go on and look really now at narrative change. It’s such a huge part of what we need to do if we’re going to address the poly crisis and your papers, all of them, seem to do this with extraordinary depth and finesse, really. And I want to quote a quote from your latest paper, which comes from Barbara Hardy. And I think it’s so beautiful. And if I’d known that it was there, I would have used it all over the Thrutopia pages. And she says:.

Manda: We dream in narrative, daydream in narrative. Remember, anticipate, hope, despair, believe, dabble, plan, revise, criticise, construct, gossip, learn, hate and love by narrative. In order really to live we make up stories about ourselves and others about the personal as well as the social past and future.

Manda: And that, that seems to me to be core of who we are and what we’re doing. And that, as you say and as you know, if we don’t change the foundational narrative of who we are and why we exist as human beings on the planet, all the rest is noise. And we’re so close to the edge of the poly crisis now. We’re so close to so many tipping points that it seems to me that changing that narrative of who we are is absolutely crucial. We know we were not born to pay bills and die, but we are surrounded by all of the extrinsic inputs that tell us that’s exactly what we’re here for and nothing else. And that conflict is at the heart of why we are where we are. You talked earlier about creating the soil in which we could plant the fertile seeds of a new narrative. In your view, how do we go about en masse creating that fertile soil?

Ruth: Yeah, a brilliant I mean, that is THE question. That is the million dollar question to pull for an extrinsic metaphor. I think there are numerous ways that this needs to happen and so many different actors can play a part in this, which for me is exciting. We’re not waiting for a saviour. We’re not waiting for the perfect NGO strategy to see this happen. This is a collaborative project in and of itself. The status quo, the way things are, the very deeply held cultural narratives that exist currently that see our world established and continue to function in the way that it does, were never brought about by one person or one organisation. They are layers and layers and layers and layers upon each other that creates their strength. And that is exactly what we need in its alternative, I suppose. So currently we have built a sort of civil society that is really siloed. You know, we have a group of actors working on homelessness over here and a group of actors working on climate change over here and a group of actors working on immigration, etcetera. And all of those issues are extremely important in and of themselves. But they are so interconnected at the level of narrative. They all have their individual kind of issue specific narratives, if you like. The narratives that exist around immigration. You mentioned earlier about certain frames that we see a lot around swarms and the fear based narratives that we see so often pushed out in our media. Actors need to to reflect on the narratives that are happening around their specific issue areas.

Ruth: But there are narratives that exist a level down, a bit deeper, that intersect. I always give the example of individualism. A really, really deeply held narrative here across the Western global north world. So deeply embedded that we see it as true. We just see it as common sense, that people are individuals and that your pursuit of happiness is your own responsibility. It’s the sort of American dream type of narrative, I guess brought large. That intersects with how we see immigration. It intersects with how we view the issue of people living without a home. It intersects with how we understand our relationship with the more than human world and how we then understand climate change, etcetera, etcetera. Actors are very rarely considering that level of work. You know, we don’t have organisations that are working on how do we replace a narrative of individualism with a narrative of collectivism? And that is what I really believe needs to happen.

Ruth: And those alternative narratives, this is how I connect my work with Common Cause with my narrative work, is that those alternative hoped for progressive narratives that we need to see embedded are founded in intrinsic values. So we need to see these new narratives taking form as a root, as a way of seeing intrinsic values be further strengthened in our cultures. Because ultimately, when we’re thinking about a different world, I almost see it as like the raw ingredients. When we have different narratives around us, we can reach for different raw ingredients to help us make a different recipe, a different way of being. And at the moment, we seem to be a lot of the time trying to make change, but with the same raw ingredients that we’ve always been using, in the sort of parameters or within the barriers of the existing deeply embedded cultural narratives that we have. So we see organisations that are very, very progressive, still replicating a narrative of individualism, for example, in their work because we don’t have anything else. And a lot of the time we’re not thinking that deeply. We think that’s all there is, you know, that’s just natural to have that narrative in place and it’s absolutely not. These things are designed and they are reinforced and they can be redesigned.

Manda: How, though? That seems to me the big question. Depending on the metaphor you use, we’re either swimming in the sea of the death cult of predatory capitalism or we’re all in the bus that’s hurtling towards the edge of the cliff. And I see so many people who are busy, you know, repainting the colours of the seats or changing the shape of the tyres. And you’re going, guys, it needs not to be a bus. Why are you doing this tiny little thing? Is this really the hill you want to die on at the point when we’re in the middle of the sixth mass extinction? How are we going to bring everyone together in an overarching metanarrative when we are all locked in the bus and/or swimming in the sea? And it’s really hard to get people to feel calm enough I think. We know from neurophysiology that when you’re under sympathetic overload, it’s really hard to be creative. Creativity requires that you’re in that rest and digest space. And it seems to me a lot of people in NGOs are permanently stressed. And so you have to tick your boxes, you have to get your strategic message out there. And it cannot Land in a world where everybody is (a) stressed and (b) still locked into the ‘who dies with the most toys wins’ narrative of capitalism. Is there any work being done on how to change the meta narrative for everybody? Starting with the people who make the meta narrative.

Ruth: Yeah, there are pockets. There are definitely pockets. I think narrative change as a practice is further along in the US, which is maybe unsurprising. A bigger country, more people, more money. So there are incredible movements and organisations there. Often being run by people with direct lived experience of the harmful, dominant narrative. And so are in a much better position to be able to direct what that replacement narrative should look like. It’s all well and good, you know, me as a middle class, white, cis woman to be able to say this is the new narrative we need when I haven’t necessarily been on the the negative receiving end of the current dominant narratives. And so there’s some incredible work happening there. I think there are conversations happening in the UK. They’re all fairly embryonic, I would say. And so Common Cause talks a lot about becoming more than the sum of our parts, thinking about how, on a values level, our work is connected, and trying to design from a place of recognition there. And you’ve got organisations like Larger Us here in the UK who are thinking more about that kind of larger narrative, that we can all come under. You have projects like Inter Narratives that’s run by Ella Saltmarsh and Paddy Loughman, which is again thinking about those interconnections between different siloed, almost issue specific narratives and how those are interconnected.

Ruth: I think these projects are brilliant and are pointing us in the right direction. But we really need to see a push from funders and an opportunity, some infrastructure from funders, to be able to bring people together across causes where maybe there isn’t direct policy overlap, but narratively and values wise, they are very, very interconnected. To understand and reassess their work in that light, kind of through that interconnected lens. That currently doesn’t happen. And it’s something that I would love to see funders create space for and be willing to explore, because it really would be a very drastic change from the way that we have worked in civil society. Well, basically since civil society kind of was born. And it requires a boldness and an ambition that sometimes I really think is lacking in the sort of social and environmental change sectors. And I really believe that people who are working in this field want to see change. They absolutely do. And they’re stressed and everything’s very urgent and they’re working against incredible odds. But sometimes I feel like, as you sort of said, we’re tweaking the system. We’re not dismantling the system. And I would love to see that level of ambition, that level of kind of boldness and courage, which we don’t always see. And maybe that’s because people aren’t aware that they’re tweaking the system and not dismantling it. Or maybe they don’t feel that they have what they need to do that. That’s a conversation I would love to see happen.

Manda: So much coming up there. Just off the top of my head, I’m thinking, if we talked about reconfiguring rather than dismantling it might be less that sense of cataclysm coming forward. So it seems to me there are some very obvious policy changes, that if we were to have a coherent government, which is clearly not in view, but let’s imagine for a moment. I mean, for instance, let’s just cancel all advertising. Advertising cannot happen. That would be a really good start. But that if Ngos and social activist organisations were to endeavour to change the narrative on their own, they would fail. Because it doesn’t matter how good your advertising spend is and how good your message is. If you’re up against people watching 10,000 hours a year of television that is saturated with business as usual, and the internet where social media is designed to harvest your dopamine levels and the race to the bottom of the brainstem is ongoing. Then it cannot possibly Land. You know, it’s not just that the soil you’re planting your seed in is not fertile, it’s been sprayed with everything toxic you can think of. And so I would suggest, and this is coming from where I live, I don’t know anything about the NGO world. But that if we could get every writer in the global North to cease to write the business as usual paradigm garbage that is coming out. I read your your blog on Barbie. People I will put it in the show notes. It was fascinating. I know nothing about the Barbie film. I would rather poke myself in the eye with blunt sticks than go and watch it. And you did it so I didn’t have to; thank you. But it sounded like it was basically two hours of of advertising for plastic dolls.

Manda: We’re in the middle of the sixth mass extinction. Why does that happen? Really I was incandescent by the time I got to the end of your blog. It’s insane. It’s functionally insane. So we would need not just the writers because they would simply be out of a job. We would need the writers and the producers and the television and the movie makers to get together, recognise that there is an issue and simply not make anything that doesn’t bring in a new way of being. And we end up in a a self-fulfilling narrative where the people with the money want to make the Barbie films because then they can sell more plastic dolls. God help us all. And as you said in your thing, it doesn’t matter if they’ve worked out a way to make the plastic dolls with a slightly lower carbon footprint, they’re still making non-recyclable plastic dolls that are designed to give little girls completely unreasonable ideas of what the feminine figure should look like. It’s the whole thing. If you landed down from Alpha Centauri and saw this going, you would get in your spaceship and leave because it’s clearly insane. Can you just off the top of your head, think of a way, even the people we could talk to, to get in the same room and go, Guys, I don’t care what you’re doing with your money at the moment. Let’s just bring it to bear on actually changing the system. Is there a group of people that exists that we could even talk to?

Ruth: Yeah, I think you’re completely right that NGOs are not going to do this on their own. The narratives that we see perpetuated that keep our world creating movies like the Barbie movie, etcetera, did not come about from one set of organisations. It has to be a cultural level shift. It has to include so many different actors. So one for me is a reassessment of the role of NGOs. So yes, there are immediate problems now that we need to have charities reacting to, because God knows the government isn’t often doing it. So we do need that. But could their role be to work in partnership with different cultural actors? The media, advertising firms, arts and cultural spaces, businesses even, to help them to reflect on their narrative and values footprint. That’s something that’s not happening.

Manda: Would they want to, though? I struggle to imagine the makers of Barbie and I’m sure there are some nice people making Barbie. I apologise to you all in advance. But I struggle to see the people who profit being prepared to not profit. At some point we have to cut that cycle. At the point when money ceases to be worth anything, it’ll happen. But I would like to get there slightly before that happens, because that’s not going to be a comfortable place for anybody.

Ruth: It would be great. Yeah. I do think that for profit businesses are the hardest to crack with this type of work. And there’s a sense of, which which way do you go? Do you stop the messages being produced by the for profit companies? Or do you work with spaces that are closely related to people? The places where people live, their day to day lives. To create the demand for that product not to exist. So we’ve we’ve seen that a little bit with the Barbie movie. So the Barbie movie, and I said this in the blog, the Barbie movie as it is created today, would never have been around ten years ago. You know, when I was in my 20s, that just would not have been a film because that would not have been profitable. So, yes, it’s still very much being measured on that kind of profit scale. But the message changed because public demand for that message changed. So there’s a sense of, yes, we can work with businesses. I agree with you. I’m not entirely convinced that businesses are going to be like, Oh, we’ve seen the light. We’ll stop doing all of this stuff, which is damaging to the planet and damaging everybody on it, regardless of whether that harms our profit margins. I’m sceptical. Maybe there’ll be 1 or 2, but I’m sceptical that that would happen. Or do you go to the spaces where people live their everyday lives and create meaning for themselves and help to build the public demand? And that for me is the place that you do it.

Manda: So we’re back to neurotransmitters again, which I completely get is part of my current obsession. But the race to the bottom of the brain stem is predicated on dopamine harvesting, basically. And the point about dopamine is that you get a very transient hit and the thing that gave you your transient hit today will not give you your transient hit tomorrow. You need something bigger and better than that, because that’s the nature of dopamine recycling. And it’s an addiction. And it’s really hard to wean people off an addiction until they really get to grips with the fact that it’s happening and have an intrinsic motivation to wean themselves off. You can’t forcibly de addict people, I would say. It worked a bit with with cigarettes, up to a point, but actually we just shifted an awful lot of people onto vapes, which wasn’t necessarily the best idea in the world. So I wonder, can you see a path where we can work with people in the spaces where they are? We could buy up all the advertising. We could have somebody like Musk. Let’s pretend there’s someone as rich as Musk, but who is intrinsically motivated. And they buy up all the advertising in the world and they just flood it with Banksy artwork or, you know, things that connect with people’s intrinsic motivation. And we create social media spaces that are decent and intrinsically motivated. That are not harvesting the dopamine, that are not deliberately creating schisms in order to have the righteous anger on both sides. If we had that, do you think that that would create a weight of opinion and feeling and I guess buying power, that would work in time? It seems to me that all of these things, perhaps if we had 200 years and everybody worked at it really hard, we might do it. And we absolutely don’t have 200 years. Over to you.

Ruth: Yeah, I think this question of urgency and time is a really good one and it comes up a lot. I guess I have two responses to that. The first being that we have been working in the way that we are working for a long time and we have not seen drastic change in the way that we need it. You know, do we carry on?

Manda: So we could do something different now?

Ruth: Yeah, that’s that’s my initial reflection. I also think that we’ve seen cultural values change happen. Covid being an obvious example. Suddenly we saw people reassessing what is important to me? How do I want to show up, etcetera? I would say that in the initial part of the Covid experience we saw a real reinforcement of intrinsic values. It was then very co-opted.

Manda: Wasn’t it just. And reverted and actually then weaponized?

Ruth: Absolutely, yeah.

Manda: By people who understand the neurophysiology. It’s wasn’t an accident. They knew where they wanted to get to and they knew how to get there and it was very effective. If we wanted an example of the fact that it is possible to completely change, if you’re ruthless enough and you know where you want to go, and you have enough money, you can make that happen.

Ruth: Yeah, absolutely.

Manda: It’s just that we tend not to want to manipulate people like that. And we don’t have the money.

Ruth: Yeah, that’s often where it comes down to is, is the money. And I wrote in Transforming Narrative Waters. This was influenced by some work that George Lakoff had done, about the fact that funding on the right, you know, it’s such a binary term but to to try and speak simply, the right funds value shift. It’s not saying, you know run this program and then come back to me and tell me how many people you reached on social media and blah, blah, blah. It’s not funding at that level. But funders on the left are totally doing that. And what we need is funding for the worldview, for the values, for the deep narratives, which is really what we’re seeing on the right. And so that infrastructure currently isn’t there and really needs to be. And I wanted to pick up quickly on something that you said around neurotransmitters. It sounds fascinating and something that you know much more about than I do. But something I’ve been playing with recently is this idea of awe, as a feeling, as an experience that perhaps we don’t lean into very much in the sort of progressive change sectors. There’s connection between awe and intrinsic values anyway, but places where awe is created. So if you’re seeing something incredible in the natural world, or a new baby is born in your family, or you are standing with a group of people and have just gone through this really interesting cultural ritual of connection and things. You know, these sorts of spaces, could we create these more intentionally for people? As a mechanism of shifting away from extrinsic values and towards intrinsic values in a way that makes people feel really happy and connected and yeah, filled with the wonder of life.

Manda: Yes. That’s what Alan Lane does with Slung Low. That’s what he did with his extraordinary January event up in Leeds. His aim was to create awe and wonder. And they had 10,000 people in the stadium and without question they created awe and wonder and gave them a sense of themselves as artists and creatives and part of a united whole. We just need basically for Alan Lane to be in charge of everything and the world would be a different place, I think. Because he is a master magician at the art of creating awe and wonder. That’s a really, really interesting idea because as you were sitting there, I’m thinking serotonin mesh, oxytocin, serotonin. I think you’re right. I don’t know the neurophysiology of awe and wonder, but when I’m teaching the Accidental Gods intention intensive, one of the things that we come back to all the time is if you can cultivate that joyful curiosity in your heart space; this is the kind of triad of joyful curiosity, gratitude and compassion. But right at the heart it is really hard to feel extrinsically motivated if what you have in your heart space is a continual pulse of joyful curiosity. And that for me is the easiest way to internalise all. And I can create joyful curiosity but it’s quite hard to create awe just sitting on my meditation cushion. So yes, that’s a really cool idea. I love it. Maybe we go out and try and get funding for creating awe and wonder around the world.

Ruth: That would be amazing. What an incredible project that would be. So fun. And so often work that you do in this sort of space feels very important, but it’s really draining work and it feels very heavy. And what an incredible project to work on, bringing more awe to the world. Not just because that’s nice, but because the power of it is incredible at shifting some of the really deeply held ideas that people hold. And I’m really interested, from a cultural angle, what does that do to us? You know, at the level of society and big communities. I think it’d be incredible if there’s any funders listening and fund this work. I think it’s brilliant.

Manda: We need to go. Maybe we need to go to Joseph Rowntree and fund the Awe and Wonder Project. That would be really cool.

Ruth: I’d sign up for sure.

Manda: We’re so, so far out of time. I’m so sorry because there was so much that we could still talk about, about changing the narrative and how we might do it. So maybe we’ll have another go next year. I’m booked into March of next year already, so sometime in 2024, if we’re all still here, the world is still happening. If we’ve managed to create the awe and wonder that we really want, we’ll come back and have another chat. Ruth, Thank you. Was there anything else you wanted to say? You’re running a course. Tell us very briefly at the end about the course that you’re running.

Ruth: Yeah, Values 101, which is our flagship introductory course at Common Cause and goes into some of the social science around values and creates lots of opportunities for people to consider the ways that their work currently strengthens particular values, and how they could shift towards strengthening intrinsic values. I’m very biased, but I love doing it. It’s some of my favourite work that I do, incredible conversations. Anyone very, very welcome to come. If you’re interested in social environmental change, there is a space for you on Values 101. I hope to see you.

Manda: Brilliant. And it starts on the 2nd of November, which is a Thursday evening. It runs from 5:00 to 7:00 and it’s running from the 2nd of November through to the 30th of November. I think it’s weekly. Is that right?

Ruth: Yeah, It’s two hours each week. Over five weeks.

Manda: Brilliant. I have put a link in the show notes, people. So head off and find it and sign up. And together we shall create a world full of awe and wonder. Ruth, thank you so much for coming on to the Accidental Gods podcast. This has been really inspiring.

Ruth: Thank you for having me.

Manda: And that’s it for another week. Enormous thanks to Ruth for the depth and clarity of her thinking. For all that she writes and does, and for being able to explain framing in ways that make a lot more sense than when I try to do it. It seems to me that in default of persuading those who lead us to cancel all advertising, we could begin to do this ourselves. You already know that I think stepping away from the mainstream media is pretty much essential to what we do. I’m thinking now also that learning to have the conversations that help people to bring forward their own intrinsic values is becoming one of the most essential acts that we can undertake ourselves. I am not trying to suggest that on our own we can completely turn the supertanker, but each of us can do something to get it to change. And I was talking last week to someone from Parents for Future, who are going to begin online trainings for how to hold conversations around everything that we believe matters. I will put a link to them in the show notes too, and I hope to be talking to Rowan at some point on the podcast.

Manda: I am booked into March. But it’s possible we may have a slot slightly sooner than that and it feels really important. So we will slot in as soon as we can. And if the recordings from the Marches Real Food and Farming Conference that I did at the weekend don’t turn out to have good enough sound. It might be a lot sooner than I had originally planned. It might even be next week. We shall see. So one way or another, we will be back next week with another conversation. And in the meantime, enormous thanks to Caro C for the music at the head and foot. To Caro and Alan for the production. To Faith Tilleray for the website, for all of the tech that keeps us moving, and especially for the conversations that hold everything together. Thanks to Anne Thomas for the transcripts. And as ever, an enormous thanks to you for listening. If you know of anybody else who wants to understand more deeply how story and narrative and framing are a key part of the solution, then please do send them this link. And that’s it for now. See you next week. Thank you and goodbye.

You may also like these recent podcasts

Thoughts from the Solstice Edge: Turning the Page on a Dying System with Manda Scott

As we head into the solstice- that moment when the sun stands still—whether you’re in the northern hemisphere where we have the longest day, or the southern, where it’s the longest night—this solstice feels like a moment of transformation.

Falling in Love with the Future – with author, musician, podcaster and futurenaut, Rob Hopkins

We need all 8 billion of us to Fall in Love with a Future we’d be proud to leave to the generations that come after us. So how do we do it?

ReWilding our Water: From Rain to River to Sewer and back with Tim Smedley, author of The Last Drop

How close are we to the edge of Zero Day when no water comes out of the taps? Scarily close. But Tim Smedley has a whole host of ways we can restore our water cycles.

This is how we build the future: Teaching Regenerative Economics at all levels with Jennifer Brandsberg-Engelmann

How do we let go of the sense of scarcity, separation and powerlessness that defines the ways we live, care and do business together? How can we best equip our young people for the world that is coming – which is so, so different from the future we grew up believing was possible?

STAY IN TOUCH

For a regular supply of ideas about humanity's next evolutionary step, insights into the thinking behind some of the podcasts, early updates on the guests we'll be having on the show - AND a free Water visualisation that will guide you through a deep immersion in water connection...sign up here.

(NB: This is a free newsletter - it's not joining up to the Membership! That's a nice, subtle pink button on the 'Join Us' page...)