Episode #101 Transport for a flourishing Future: Zero deaths, Zero Emissions, Zero Carbon: with John Whitelegg

As we lurch towards irreversible climate chaos, how can we begin to pull back from the edge? This week, we look specifically at the area of transport: how can we be mobile and yet reach the 3 Zeroes of Death, Emissions and Carbon? What would it mean to live in an area with fair, free, extensive public transport? And how can we make this happen? Our lively, inspiring conversation with Professor John Whitelegg has answers.

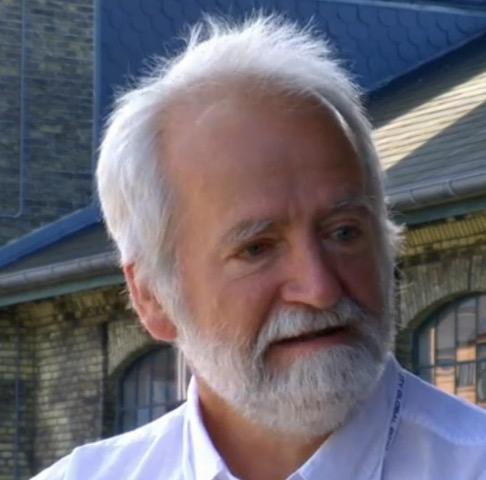

John Whitelegg, BA PhD LLB, is visiting professor, School of the Built Environment, Liverpool John Moores University and was formerly professor of geography and head of department at Lancaster University and a staff member of the global science policy organisation, the Stockholm Environment Institute. He has worked with the Wuppertal Institute for Climate, Energy and the Environment (Germany) and is an associate of the Kassel Centre for Mobility Culture (Germany) and a board member of the Californian organisation “Transportation Choices for Sustainable Communities”.

John has edited the journal “World Transport Policy and Practice for 25 years and has written 10 books. In the most recent book Mobility, he presents an evidence-based case for a transformation of the totality of transport and mobility policy to achieve three zeroes (zero carbon, zero deaths and injuries and zero air pollution). He has also worked extensively on practical measures to achieve 100% decarbonisation of land transport.

In this episode, we talk at length about what needs to happen in our transport systems to bring about the three zeroes of death, emissions and carbon. John has travelled widely and worked in Germany, Sweden, and the outer Hebrides as well as many locations in the UK. He has a coherent set of ideas of what needs to be done – and we considered some of the ways ordinary people can begin to make these happen.

In Conversation

Manda: My guest this week is a huge help on that path. I haven’t had so much fun recording a podcast for a very long time. Dr John Whitelegg has been, amongst other things, visiting professor of sustainable transport at Liverpool, Professor of Sustainable Development at York’s Stockholm Environment Institute. And he is currently a fellow in transport and climate change at the Foundation for Integrated Transport. He’s written massive numbers of papers and books, including a small book called Mobility, which is available on Amazon. He’s one of the most articulate individuals I have ever met on the subject of how we get about; how we do it now, how we do it wrong and how we do it right. And for those of you not familiar with British geography, he and I both live in Shropshire, so we did use that quite a lot as our models. Although the Outer Hebrides, for those not in the UK, are a particularly glorious set of islands off the west coast of Scotland. Very beautiful. If it wasn’t that it would take a lot of carbon, I would say well worth a visit, but you can look at pictures. And in the meantime, people of the podcast please do welcome Dr John Whitelegg. So, John Whitelegg, thank you so much for coming on to the Accidental Gods podcast. It’s been such a long time since I first heard you talk about transport in a way that opened everything up, and I realised that we do have answers. It’s just that we’re not necessarily applying them. So thank you for coming. And how is the world about 20 miles north of where we’re sitting at the moment up in Shrewsbury?

John: Well, the world is fine in Shrewsbury. It’s a very beautiful town and a very pleasant, better than pleasant place to live. Like many parts of the UK, we’re suffering from lots of difficulties related to the kind of boring stuff I’ve spent my life looking at. Climate change, air pollution, health problems. Shrewsbury is an extremely beautiful place, but it’s very unpleasant in the way the streets are dominated by traffic. Children have a very tough time moving around. It’s almost impossible for children to walk and cycle to school. Children therefore, therefore don’t get enough physical activity, and that’s important for their health. They don’t get enough experience of finding, though, of navigating their way around places and squares and streets and parks and woods and so on. And I often, though, it gets a bit boring when I talk like this, I often think back to my childhood, which was in a very boring industrial town in Lancashire in the 1950s; where I had complete freedom. We had no traffic on my street. Nobody bothered if I went for a five six seven eight mile walk, if I went on my bicycle. The town I grew up in Oldham, I even used to walk to the railway station and get a train to Manchester when I was nine years old and walk around Manchester and rather enjoy it and find my way back to the station. And I often look at things through the lens of children, and I think things have changed so much now negatively and unhealthily. And climate change is part of that and air pollution is part of that. But we’re depriving children of learning and growing and expanding and being able to see things properly and make decisions properly. So we’re actually storing up mega problems. So Shropshire is delightful. Shrewsbury is delightful. It has all the right characteristics, but everything that should not go wrong is going wrong.

Manda: Yeah, and not just Shropshire and Shrewsbury. So before we get onto what’s going wrong and then how we could put it right, let’s take another walk through how you got from getting on the train at nine years old in Oldham and going to Manchester, to being the fellow in transport and climate change at the Foundation for Integrated Transport. Because it’s been a really interesting life’s journey. Can you give us the edited highlights?

John: It’s it’s something I would like someone to answer for me, but I mean, a lot of things I think – do people still use the word serendipitous or serendipity? You know, I think like many people, I pursued my own interest because I was interested, so I was fascinated by geography. But the difference being places and how one place operates, and another place operates. Why is it very different to live in London, to live in Lancashire? And what makes place identity? What makes place character? So that Strand has taken me through the last…I don’t even like to do the counting… The last 50 years. Via a whole series of serendipitous things, you know? So for example, working with the Department for Transport in London on mathematical models of freight flows, which I now look upon as totally tedious and irrelevant. But it was a good way to try and understand the way that government works and the way that science works and the way that information can be collected and deployed. And then deciding back to places that I wanted to do something very different. So I became the transport and economic development officer in the Outer Hebrides.

Manda: Oh, brilliant.

John: Responsible for running ferries, inter-island air services, setting up post buses, looking after the the tweed industry, the seaweed processing industry and helping lobster fishermen and crab fishermen to do their work.

John: A remarkable time,dealing with people and dealing with different ways in which people earn a living and different ways in which people enjoy the very distinctive environments in which they live. I’ve still got that now. And that’s why I’m interested in transport, because I think I think we’ve got so many things wrong. But the good news is it’s dead easy to get it right. It really is easy to get it right. And then I benefitted a lot from three years working in (my German is appalling) I worked as a German civil servant in Düsseldorf, responsible for transport planning in Cologne, Dusseldorf, Essen and Dortmund, a state in Germany of 16 million people. And I learnt there and I’m going back to 1990, that it is possible when you’re dealing with intelligent people to get things right. And what I mean by right is we need wonderful walking facilities, cycling facilities, fantastic buses, fantastic trams, fantastic trains, 100 percent no oil, no gas, no nuclear. And we need to do it all properly so that people benefit.

John: And when people have a good quality of life because they benefit from excellent transport options, and that’s part of quality of life. Interestingly it means low air pollution and interestingly it means low carbon and interestingly better health. So I’m still puzzled and still trying to work it out, why, as a Danish friend once said to me, “Do you in Britain try to do things badly and you’re just very good at it? Or was it all Accidental and you just don’t know what you’re doing?” Now he’s a very nice man, and he was very supportive of UK work and effort. But we do things so very badly. We’re drowning in evidence about how well it can be done. It can be done so much better. And I spend my time now as I did 40 years ago, trying to work out better ways of doing things. And basically, if they convince people, I think people used to use the phrase ‘changing hearts and minds’ or something like that, you know, how would you change things for the better? And that’s what I do now in transport and mobility and climate change and air quality and public health.

Manda: Oh, John, can we not just elect you Prime Minister, now? It would be so much better! Because that is a fundamental question. I don’t necessarily want to spend the whole time discussing the politics of Britain because half of our people listening don’t live here. But that question of do we deliberately set out to do things wrong and we just happen to be very good at it. And you’ve worked you said you you began life counting freight trains and helping the government and beginning to understand how government worked. And you’ve looked at government in Germany. I am just awestruck that you were in Germany for three years and it’s a neoliberal government. It’s a hardcore neo liberal government. It is the whole…if you ever read Yanis Varoufakis ‘Adults in the Room’, what the Germans did to Greece was an obscenity. And yet, they clearly have some better ideas than ours. And I wonder, is it just the rampant corruption of the Tory party that, you know, the guys who destroyed the rail system were the people who owned the companies that built the roads, has that just been going on for so long that corruption is what makes it so desperately inefficient? Or do they just have some kind of very weird English ideology, separate to the neoliberal politics and economics? Does that make sense as a question?

John: The question makes total sense. I always feel very inadequate at this stage in any discussion because I probably think about that question or related questions every day. I’ve concluded having worked in Germany for three years and then I worked in Sweden as well. I worked with a Stockholm Environment Institute who are a globally significant organisation for dealing with climate change and transport, for example. I’ve noticed a few things in those two countries. First of all, there is there is no dominance of people who have been to public schools or people who have no real experience of living in places like Oldham. You know, dominated by people who have ended up in powerful positions and influential positions and the old story’s revolving doors. You know, they become advisers to politicians, they become cabinet members, they then go and work for a global multinational company. And that’s very much in the news at the moment with our corrupt, sleazy conservative party politicians in the limelight again. And it’s not necessarily a criticism of the Tory party per say, but we have this kind of…it’s basically the class system. You know, we have we have a system in Britain whereby if you go to the kind of primary school I went to in Oldham and go to a kind of a second rate secondary school in Manchester, you don’t end up working at a high level in UK parliamentary contact. You don’t end up being an adviser to a minister. You don’t end up being a member of Parliament.

John: Usually you don’t end up being in cabinet, you don’t end up working with multinational companies. And the thing I’ve noticed in Germany and Sweden is they are very, very egalitarian. It’s a flat – both of them are flat countries. And as part of my research over the years, I’ve actually interviewed (this is in another book) the Lord Mayor, I suppose we would call it the England, of the City of Freiburg in southern Germany. Freiburg is interesting because it locks up international prizes every year: Green City, innovation city, solar city, you know, it’s just a world leader. And sitting with the the Lord Mayor, the burgermeister of Freiburg, you know, an ordinary person who’s done lots of his own work in universities. No public school, no advancement because of Family Connexions, no wealthy background, just hard work and getting on with things and developing intelligent ideas to solve basic problems. And I’ve seen that constantly in Germany and constantly in Sweden. And even though I get in trouble for saying it, I don’t see that in Britain. We don’t have a system where ordinary people with great intelligence, not not a product of the class system, arrive in positions where they can actually have an influence and change the way we live and work. Now, probably people would argue that that’s a completely misread assessment or interpretation of where we are. But I can claim that having worked in Germany for three years and having worked in Sweden having, for example, interviewed Swedish counsellors. Some years ago, I was actually a councillor myself and at that time the UK Local Government Association -So not me, not me being rude – The UK Local Government Association concluded that councillors were ‘male, pale and stale’, and they use those three words. And there was there was an outcry! Now when I interviewed councillors in Sweden and in Germany, over half of them were women, and over half of the women were under the age of 40. Now, I don’t think age matters terribly in this sense, but it means that very often they were involved in all kinds of situations where they were balancing ordinary life and families and children and a whole number of things. So immediately they saw what I was talking about. When I sit down with a group of ‘pale male and stale’ UK politicians, they don’t understand why we should have streets not drowning in fast moving traffic. They don’t understand why children should be able to walk and cycle to school safely. They think like a former leader of Manchester City Council, they think that lots and lots and lots of traffic is a really good sign of a vibrant economy, and they want to keep that going. So we’re dealing with a very, a very skewed, a very peculiar social cultural political system in Britain, and I’m the first to confess I don’t know how to change it. I still focus on things very much that I think have the potential to change it, and we might talk about these things later. You know, so for example, I talk about why we must have totally free public transport for everyone in Britain.

John: We must have every town and city totally car free. We must have certain, you know, there are other things on that same list about really what some people will call ‘big ticket items’, I don’t know. I call them just ‘transformational’. We need transformational measures and interventions to improve quality of life, deliver social justice. You know why should a single parent possibly more likely to be a mother, you know, in a flat, in a boring, treeless area have to suffer large amounts of air pollution and traffic danger? You know, we need to improve and we can improve all those things. We can have zero air pollution. We can have zero carbon. And like Sweden, which is why I’m attracted to Sweden, we can have Vision zero. Sweden has a policy which is implemented on a daily basis, and I’ve been there and interviewed everybody about this, there will be no deaths and there will be no serious injuries in the road traffic environment. A mistake in the road traffic environment must not involve the death penalty. When I introduced this idea to politicians in the Department of Transport in London, they laughed. They said “It’s unrealistic. And by the way, we’re the best in the world at road safety, and we don’t need to look at Sweden”. Now that sums up the situation very well. I might not have got the story right about public schools and people not having real experience of real life. I might not have got that right, but I’ve heard that said many times.

John: So they rejected Swedish Vision Zero. That came in in nineteen ninety seven. And also in Sweden, that same thinking in Sweden applies to the nature of our towns and cities. Where I lived in Sweden in a very rural area, I had 26 buses every day between 6:00 in the morning and 11:00 pm. But when I talked to Shropshire councillors about lovely places in Shropshire like clun, you know, and places in rural areas in Shropshire, some of these places haven’t seen a bus since 1934! You know, and in Sweden, there’s 26 a day on a weekday and 10 on a weekend. Shrewsbury bus station is the only bus station in Europe that I know of, totally closed and locked up and shut on a Sunday. Buses are forbidden in Shrewsbury on a Sunday. Now that, when I tell my European friends, my Swedish transport planners, they fall about laughing. They say, you’re making it up. No country could be so stupid as to close a bus station. I say come and have a look; The shutters are down it’s locked. And what you never see in Shrewsbury bus station on a Sunday or a bank holiday is a bus. Now that sums up the situation, so we don’t really need me to provide a social, political, cultural explanation. We are bad. But the really good news is we know how to improve it, and I try and do everything I can every day to improve it.

Manda: All right, so let’s do that. Because we’re recording this in the beginning of the week after COP, which was a fairly distressing experience to watch; the male pale, stale autonomy and hegemony seems to have managed to make sure that nothing really happened there, except a lot of greenwashing. So let’s cheer ourselves up with a sense that we do actually have answers and that a lot of those answers, as you said, work in other countries. So they work in Sweden, they will work elsewhere, if we could get the political will. We’ll park how we get the political will, perhaps for another podcast. You have a triple vision zero, which I read of in your book Mobility. A link will be in the show, notes people. It’s well worth a read and you can get it on Amazon. So let’s have a look at if a miracle happened; Boris Johnson woke up tomorrow morning and ceased to be a public schoolboy and became a normal human being and thought, I want the best person in the country to come and sort things out, and that’s John Whitelegg. And he said, “All right, come in. You’ve got as much money as you need and we will listen to you and we will implement this in a way that that goes right across all of the departments”. Mariana Mazzucato, sensible thinking. What would we do?

John: I’d focus on transport, of course, but a lot of the thinking that goes into my approach to transport is shared with other what I call other themes, other issues. But I won’t stray into, for example, every home in Britain should be retrofitted with the best energy efficiency, high quality insulation and reduce the energy bills of the population by 90 percent. We know how to do that, by the way, and Germany once again, Germany has pioneered the passive house concept. So when I talk about transport, I like to make Connexions really with other areas. But in transport, we’re very lucky in transport because we have people actually doing the right thing day after day after day with evidence on the ground. So what I try and do and often what I suggest to politicians, but no one ever says, “yes, let’s do that” I say, “OK, please come with me to Gothenberg in Sweden, a very large city, it’s over a million people and the streets are not entirely but largely car free. A totally integrated walking, cycling, tram, bus, local train system, all affordable. Where I lived in rural Sweden I had one ticket, one ticket for public transport that covers all buses and all local trains in any combination for any distance, as long as you can do your trip in seventy five minutes, which is a particular Swedish approach. And that was £3 anywhere, any time, any combination.

John: So in answer to your question, what I would say is that we don’t need to go into huge volumes of consultancy studies about how we plan it in detail. We want the Gothenburg system. Oslo, a capital city with over a million people, is car free. We want Oslo, car free. Last year and the year before, Oslo reported zero deaths in road traffic. Zero. If you look at places that I won’t try and remember statistics, it’s never a good idea. But if you look at Birmingham, Manchester, Liverpool, Newcastle and Leeds and say “how many people were killed in road crashes?”, I don’t like the word Accidental because it implies somehow it can’t be avoided. In road crashes. And usually in a British city you’re looking at, nothing matters very much; 20, 30, 40, 50 deaths in a year. Oslo zero. Now we need to look at Oslo and say why? We need to look at Freiburg in southern Germany, for example, which decided they needed a lot of new homes. Now we have a big debate in Britain about housing shortage, and we need lots of new homes. So what we do normally is find a big green field somewhere, build lots of executive style houses, give them free parking places and then maybe say, “Oh, by the way, we’d like you to use the bus”, but there aren’t any buses or we’d like you to cycle. There aren’t any cycleways.

John: It’s not long ago, and I shouldn’t even mention it because it’s upsetting that a young lad, 18 years old, was killed walking along the roadside in Bishop’s Castle in Shropshire. That should never happen. An vision zero it wouldn’t happen, because steps are taken to provide the right infrastructure to make sure it doesn’t happen. So basically, we on the housing side, for example, we would do a Freiberg. We would have car free housing. Now again, a British politician at this point would need to reach for the defibrilator! Because car free housing is something, you know, it’s a bit like you’re saying Catholicism is better than Protestantism or something, you know, they take it very, very seriously. But we have 20000 people in Freiburg living in car free housing. And before they built that housing on what we would call a brownfield site, they insisted on building a new tram system that went there first. So again, we know what to do. In terms of high quality integration. Why is it that Craven Arms and (I’m back to Shropshire I’m afraid) why is it that craven arms and church Stretton train stations never, ever, ever see a bus? They don’t. You know, again, my German colleagues and my Swedish colleagues, my bosses in rural Sweden always connected with trains.

John: They always had a screen on the bus telling me the times and the platforms of the trains that the bus was going to connect with. So in Shropshire, we accept that buses and trains are like totally different species, and they must never connect with each other. And we have excellent, most German places and Swedish places do that connexion. In in Switzerland they do it to a degree; I suppose some people would call it the cuckoo clock or something. You know, they do it really, really, really perfectly. And in a precision sense, in Switzerland, if you’re above, say, six or seven hundred population, like many of our places in Shropshire, by law, you must have bus services. And they must service the nearest train station. They must service the nearest GP hospital, they must service the nearest shopping centre. So my point in this in answer to your question. Actually, we can look at examples that currently are there. They exist. And we can go and talk to them. So we can talk to Oslo about car free. We can talk to Switzerland about rural public transport. We can talk to the Swedes about the 26 buses a day in a rural area. You know, we know what to do. We can talk to everybody who does it well. Cycling. I’ve produced a report recently focussed on some Shropshire, focussed on the Ludlow constituency of Philip Dunn MP, and asking for a totally segregated network of funded cycle paths connecting every school and every college with its main catchment area.

John: I will not have people walking along on roads like that Bishop’s Castle tragedy. We can have totally connected, totally segregated, traffic free, part of Vision zero, totally safe side walking and cycling facilities. Now my guess is that will go nowhere, but it doesn’t stop me asking for it and arguing that it should exist. So we know how to do that. We know, for example, we can copy Oslo and have car free towns and cities in Britain. We all complain about poor air quality. In Britain we think we’re doing well because we only kill 40000 people a year from poor air quality. Well, what’s 40000 people a year? Boris Johnson, when he was mayor of London, ignored totally the air quality problems of London. We know how to deal with air quality. And if anyone has ever done what in pre-COVID times, I used to walk a lot up and down the road between Euston and King’s Cross. That’s because I won’t bore you with what I was doing, but it was to do with my work. And looking at that road, it’s an absolute disgrace. It’s dirty, it’s polluted. The pedestrian facilities are rubbish, the cycling facilities are rubbish. The air quality is appalling.

John: The carbon is appalling. Everything is appalling. And not only me, but many others argue for sorting out roads like that one. Totally ignored. Boris ignored everything when he was mayor of London, and he’s now carrying on the good work as the prime minister of the United Kingdom. So, you know, we have a problem with our politicians. But the really good news, and I do think it’s important to emphasise good news, is I can take any UK politician to a number of destinations in Europe. There are even good places in Latin America. There’s a car free housing development in Phoenix, Arizona. Even the Americans have got the idea of car free housing. If you can build car free housing in Phoenix, Arizona, you could do it in Shrewsbury and Ludlow and Bridgnorth, you know, but we don’t. We want to fill big green fields. So the really good news is we’ve got the examples. The people doing it are intelligent, they’re kind and helpful. They’ll tell us what to do and how to do it. We can bring that back and we can do it here. So the main problem is how do we persuade, how do we how do we change things here so that politicians are willing to learn from best practise? And that’s where I really do need help. I don’t know how to do that.

Manda: So I’m looking as we speak at the C40 Cities network, which now I think is 172 cities and they have, I’ve just looked up a mass transit network, and I’m looking at the bottom. So they’re their website says ‘C40 mass transit network is focussed on infrastructure as well as the physical and operational integration of transit’, and The Future is Public Transport Campaign is inherent to what they’re doing. And down at the bottom it’s got cities participating in the mass transit network are: And there’s a list starting with I don’t even know how to spell or pronounce the first one, but the second one is Addis Ababa, which is a leading city right all the way through to Seattle, Singapore. And London is in there, which amazes me. Also Buenos Aires and Barcelona and Ho Chi Minh City and Johannesburg and Los Angeles and Moscow and Phoenix and Rio de Janeiro. So there’s seriously big cities in there. And so I’m wondering on a political level, whether it’s people like the mayors who often, so the mayor of Liverpool, you know, Andy Burnham, isn’t a standard public schoolboy. I’m wondering whether at mayoral level around the world when our government seem to be being captured by very hard Alt-Right strongmen, whether at city level, there is more work being done. Is that’s something that we can work on do you think?

John: This is quite a problematic discussion because the C40 network, for example, I track them a bit and I’ve had a discussion with them about the mayor of London’s support for the Silvertown Tunnel. A two billion pound tunnel to add extra highway capacity to increase carbon emissions and increase air pollution in those parts of London. Supported by the mayor of London and supported by C40.

Manda: Oh Dear.

John: So I think we are into… I’m not going to try and rubbish everything they do, because I think there will be a mixture of the good, the bad and the ugly. But C40 are largely into greenwash and spin and image, and what we need is the mayor of Freiburg or the mayor of Gothenburg or the mayor of Lunt in southern Sweden and many other places I can name who don’t bother joining possibly wishy washy, green washy organisations and produce a lot of marketing type publicity, but get on and do the job. They change things for the better. Right now, I want to be clear; I don’t know enough about C40 to… I’m not going to dismiss everything they do as being rubbish. But I’m stung by the support of the mayor of London for the Silvertown Tunnel and of C40 for the Mayor of London for his support of this Silvertown tunnel. Things like the Silvertown Tunnel, like the Shrewsbury North West Relief Road and like a whole number of other things that are going on; Britain is quite, you know, it’s not unique, but we do it very well.

John: We’re spending twenty seven billion on new roads supported by the majority of politicians. We’re spending those at what’s called national roads, right? We’re spending an additional seven billion on local roads. That includes the Shrewsbury North West Relief Road. And we’re spending and in the last budget, we reduced the cost of flying and we reduced the cost of driving. And then we turned over COP26 and said, we’re world leaders. You know, so I can’t disguise a certain amount of grumpiness and a lack of conviction or rather strong view that we’re dealing with a lot of hypocrisy. So there is a lot that can be done by mayors, but I don’t see any sign of that in London, Liverpool or Manchester. Those are the ones I know best, so I’m not sure what they’re up to in Leeds, in Newcastle. But yeah, you know what matters is what they actually do to change things. And Liverpool, the mayor of Liverpool, Merseyside or Liverpool, are supporting new role building. They are in Manchester, they are in London, right? And in Shropshire Council, the North West Relief Road. I worked out that the North West Relief Road would generate an extra 70000 tons of so-called embodied (That’s before you get a vehicle on it) embodied carbon.

John: That means if you build things with lots of steel and lots of concrete and lots of cement and lots of tarmac, you’re immediately in trouble. You’re adding tens of thousands, hundreds of thousands. And in terms of really big projects like HS2, which is very controversial, HS2 is adding something like 90 million tonnes of extra carbon because we go down the infrastructure. And most mayors support infrastructure. So I’m not qualified enough to provide answers to all these these issues. But I want mayors, particularly, to deliver an Oslo, a Gothenburg, a freibourg and I would love to take them to Zurich and Geneva, these places. Again, I’ve worked in Switzerland and to stand at a small place Dornach in Switzerland, which is a bit like Bridge North or Ludlow or Bishop’s Castle, you know, it’s quite a small place in Shropshire and to stand there when a train comes in. And at the same time that the train comes in, eight buses turn up to meet the train and go off to all the villages around and a tram turns up and the Swiss have invented something called pulse timetabling. No British politician knows anything about pulse timetabling. Pulse timetabling is that you coordinate all these different things so that when one of them turns up, the other things turn up and people get out of one and get on the other!

John: So It’s very, you know, it’s a bit like nuclear physics isn’t it. Very complicated, isn’t it? It’s very hard to understand pulse timetabling. I watched it in Dornach. And and when you see 50, 70, 80 people get off a train and within five minutes, they’re on the little buses heading to tiny villages and they’re gone. Okay, so for five minutes, everything is really, really, really busy. That should happen outside Ludlow train station, back to Shropshire, I’m afraid. That should happen outside Church Stretton train station. We do nothing. We are dopey and we do not learn from anybody. So back to your point about C40. Yeah, they may do good stuff. They do draw attention to the importance of dealing with climate change in a city governance context, if you like. But why do they end up supporting the Silvertown tunnel? You know, there used to be – I’m out of touch with theology and Catholicism and Protestantism – but if, like me, you went to a Catholic grammar school, you’re a bit scarred by it, you know, through life. We used to use a mantra, something like ‘by their actions, shall ye know them’

Manda: Right. Yes.

John: You know, so sometimes a bit of theology, if that’s what it is, comes in useful. Cut the waffle, cut the the greenwash. What do they actually do to make things better and they’re not doing enough.

Manda: Ok, yep, I hear you. And it’s deeply distressing. However, we are still trying to find solutions. I have a question on if we are to do what we need to do for climate change; so you have three zeros. So, Zero deaths on the road, we’ve touched on that lightly. Zero emissions, we touched a bit on that and zero carbon. In order to, particularly because that’s the one that really frightens me, to get carbon down to where we need to, we have to cut the road transport and the way that we just burn fuel to take one person from A to B.. What is the embodied energy? Have you calculated it? In setting up the necessary Tram systems or bus systems or public transport systems to replace the cars, because I’m thinking we’re heading to the point now where we’re going to have to burn a certain amount of carbon to get to a solution, and it may be that burning that amount of carbon takes us over 1.5. Has anyone done that level of calculation?

John: The simple answer is no. It can be done, but it requires quite a lot of effort to do those sums. The embodied carbon thing is very important, and we do know a lot about that when it comes to things like roads, bridges and tunnels and HS2. We know a lot about that. So we do know that that total of carbon embodied is unacceptably large and actually contradictory to climate emergency and reduction strategies and plans and targets. We also know when it comes to this is back to fundamentals of my favourite word ‘transformation’ when it comes to mobility, transport moving around. We do know that walking and cycling, which for all practical purposes we can regard as largely embodied energy free, embodied energy Zero. Ok, there will be an embodied energy in a cycle path. But when you’re talking about something that’s two metres wide and you know doesn’t require bridges and tunnels, you know, it’s very low. But the smart thinking around the world, and I’m not including me in that, is that we need to put a lot more effort into how we promote walking and cycling, which is not just about road traffic danger or cycle paths. I have a German colleague who who talks about creating the city of short distances. This is another example of German smart thinking and intelligence that cuts across all kind of normal ways in which we divide things up.

John: Now, ‘the city of short distances’ means that what we would actually do is have a complete approach to planning and housing, retailing and hospital services and GP’s and other things we need. All in a system that made those things available within relatively short distances of where we live, right? And those relative short distances will be quite copable with, by walking and cycling and indeed by small electric buses, for example, that fits in the picture as well. So we can’t deliver the city of short distances just by talking about walking and cycling. We need a complete transformation again of the planning system, and many planners have talked quite eloquently for many years in Britain about how we’ve gone into massive suburbanisation. We use phrases like urban sprawl, suburbanisation. So even in a place like Shrewsbury, you know the amount of house building that’s way out of town in big green fields, which adds to distances which makes homes car dependent. So we know we’ve got to get that right. Now the relevance of all that is the embodied carbon, go back to embodied, the embodied carbon requirements are very small. There will be some, but they are very small. It’s only when we get into motorised transport and within motorised transport, it gets really quite tricky and quite controversial.

John: So, for example, the promotion of electric vehicles and we all want to see the end of petrol and diesel vehicles, you know, apart from the fact that they’re killing 40000 people a year. That’s a good reason for getting rid of them. But replacing them with the technology we have available; battery based electric vehicles. The embodied energy in batteries and replacing batteries, for example, is quite large and people have done studies on that. And when they do those studies and it gets really techy and I’m not qualified to talk about the real techie stuff, you know, the actual carbon gains from electric vehicles are quite small and can be negative. They can actually add to carbon. There are still reasons for getting rid of petrol and diesel, which is why it’s a complicated picture. But what we tend to forget in Britain is that we need a total mobility transformation. A Mobility revolution. The majority of our trips, and they manage this in Freiburg in southern Germany, interestingly; the majority of our trips should be walk, cycle, public transport. In all possible combinations and all affordable and all reliable, very reliable indeed. And I think in Freiburg, they’re now down to something like 20, between 20 and 25 percent, of all trips every day by car.

Manda: Wow.

John: Now, I don’t know. I’ve asked for Shrewsbury data, for example, but there isn’t any. We solve a lot of these problems in Britain by not collecting the basic information that we need because information can be unhelpful in doing what we want to do. But my guess is and I taught this for years when I taught transport at Lancaster University, you know, the normal thing in a British city is sixty to sixty five percent of our trips every day by car. Now in a German city, they managed quite well at twenty five. Right? And they’re even keen to get that further down. And twenty five percent are by bicycle. Now I do know that in a British city and this does apply to Shrewsbury that our cycling share, if you like – it’s difficult to count these things properly I admit that – but our cycling share is less than two percent. What that means is if you could count every trip, every journey made by everybody, every day and how many were by bike, then you would actually come up with a number that’s less than two percent by bike. That can be twenty five percent. And bikes are actually I mean, many people have looked at bikes over the years. You know, they they’re very undemanding in terms of energy and carbon.

John: They’re zero pollution. They promote public health. We have a huge health discussion about so-called ‘active travel’. And again, part of my strange career, I was part of an expert working group with the World Health Organisation in Geneva, producing the Global Action Plan on physical activity. The one thing about the W.H.O. is they don’t do things on a small basis. They produced a global action plan, which I was involved in, they communicated it to 170 countries around the world, saying, Please do it. Britain ignored it. The global action plan says we must have 20 mile per hour on streets where people live, because that encourages walking and cycling and people are put off walking, cycling because they fearful of the danger. Right. Shropshire Council is remarkable. It has rejected 20 mile per hour. Totally rejected it for full discussion. Full council, Shire Hall, Shrewsbury rejected. No information, no evidence, no public health data, no evidence, just councillor after councillor saying “I don’t like it and it won’t work”. Now, when you get to that level of, shall we say, irresponsibility, I’m trying to think of nice words. When you get to that level of irresponsibility, you know, we’re not going to produce solutions, but we do know that we have solutions and we do know that when it comes to embodied carbon, we need to get that walking and cycling up, easily up to one third.

John: There are people around the world and I am part of that kind of thinking, you know, we talk about the rule of one third as a guide. You know, we can’t produce a system where… And in rural areas as well…there’s a temptation in England, especially, to say “rural areas? No chance. Everybody should use a car. That’s it. End of story” But we can have a rule of a third. One third of all trips every day walk and cycle, one third of trips every day, public transport, one third of trips every day by car. And we can do it. So we can solve the embodied carbon thing, but we’re currently locked into a kind of an embodied carbon fetish. We love, as a country, building roads, tunnels, bridges, high speed rail. HS2. We could solve all our trade problems without building a completely new railway line that goes through the countryside and has lots of tunnels and destroys thousands of trees and uses thousands of tonnes of steel and concrete. But we won’t because we like – we’re like small boys with a Lego kit or meccano kit. We’re like playing big boys, big toys, and that’s what runs our system.

Manda: Oh John, it’s so distressing. But you sent me a paper yesterday and that other city centres… So cities in the UK; York banning private cars from the city centre and Brighton and Bristol. And it seemed to me that they all had a kind of three year phase out that started in 2019. And I’m wondering where that’s going and particularly what occurs to me is part of the reason the politicians do what they do is that they think everybody wants to own a car and it’s hugely popular and there must be a cultural difference in the countries that manage the much more cycling. I’ve been to Amsterdam, everybody cycles everywhere and it’s safe. And you’re absolutely right. I would love to cycle to our village shop to go and pick up the paper, but I would be dead by the end of the week.

John: Yeah, yeah,

Manda: It’s genuinely unsafe. And so we need the cultural change first or in tandem, which would mean we would have to have politicians who are prepared to make the weather instead of being weather vanes. But there are cities in the UK or towns that are doing it. How are they managing it?

John: Yeah, you’re quite right. I mean, there are very good signs of the… I’ll call it German and Swedish thinking, you know, in Brighton, in York, in Bristol, and there may be more. For example, I read very good reports about buses in Reading and buses in Nottingham. You know, there are some, you know, original, intelligent, sustainable, low carbon, public health oriented ways of thinking going on. And we do need to celebrate that. Your question is, a very fundamental and difficult point that I think about a lot. Which is when you do meet groups of politicians like the Shropshire council debate about 20 mile per hour, who are just simply not prepared to look at any evidence, look at any best practise, look at any examples and they just determined to carry on. I think what some people call this, there are trendy phrases (I don’t understand). ‘Path dependency’ is one I’ve been told about by academics. Basically, if you if you set your stall out to do something, you know, and you’ve been doing it for 10, 15 or 20 years, you don’t stand a cat in hell’s chance of changing that trajectory, you know, and that’s kind of like sociological and psychological stuff. I don’t really buy that. And I don’t know, the details are how they’re getting on, especially in York.

John: York has made very clear decisions to be car free and because of the distinctive nature of York, they can talk about car free within the city walls, you know, because the Romans were kind to us and other people, presumably… They weren’t kind, but presumably, historically somebody helped by building a wall around York. I argue the same in Shrewsbury within the River Loop, because the River Severn’s very convenient. You know, it goes in a big loop around it. So we can do car free. And I think what needs to be done is, I wish I could think of the right language… Is a bit more kind of genuine leadership from the front.

John: You know, in other words, if climate change is such an enormous problem – and if anybody thinks it isn’t, then we are doomed. You know, it’s such an enormous problem that we need to do things differently and with enthusiasm and get transformation. If we really do think that, then what we have to do is start changing our whole approach. So, for example, we can adopt totally free, fair public transport, which I’ve been researching. We can adopt car free towns and cities. Every town and city in Britain should be car free, like York, like is being discussed in Bristol and is being discussed in Brighton. Oslo’s done it.

John: It is there I went to. I went to Oslo and looked at it and wandered around in a daze, enjoying lovely streets and trees and all sorts of public facilities and lots of people and no cars. You know, it’s fine, you know, in other words, we know what to do. I think this cultural thing that you raised is more than interesting. I don’t think it is a cultural thing in the way that would excuse not doing the right thing. Now that sounds a bit bonkers, doesn’t it? In other words, I think if people can be persuaded to do the right thing, for example a car free city, you know; then I think that the population at large would behave in exactly the same way that they do in Oslo and Gothenberg and Lunt and Freiburg. In other words, we are all human beings, I think. We all operate in roughly the same kind of context, you know, earning a living, thinking about family, doing our stuff, you know, we’re not that different. Where I think the differences are, especially in a German city because I had that three years wonderful experience during transport planning in several German cities, is because they’ve done the right thing every year for 30 years, one year after the other. If we do anything right in Britain, we do it for a year and then we cancel the budget.

John: We have a plan to improve buses and we give money to buses for a year and then we shot down that budget. In other words, we have no continuity. We’ve no building upon successes. We have no no idea at all about about how to change the way people think and move around. And if you keep chopping and changing, then people will fall back upon something in their control. And the car. I’ll Be the first to admit, the car, especially with living in rural Shropshire, for example. It’s yours and you can control it. So why would you worry about that bus that runs every two hours and didn’t turn up last week or whatever? You know, you’re going to make a reasonable decision to use the car. So what we’ve got to do is not somehow excuse doing the wrong things, because and I know you’re not saying this by the way, but I do get told this by people when I say people get cross with me and talk about Germany and Sweden and Switzerland. But we’re different, aren’t we? Well, no, we’re bloody well not different. You know, if you do the right thing for 20, 30 years and you get an excellent system in place; if you live in those car free areas in Freiburg, for example, where you got excellent cycle paths and you’ve got an excellent tram system and there’s no car parking provision, that’s a bit of a clue, isn’t it? You know, then you will actually make the right kind of decision.

John: And that’s fine, you know, so people manage very well. We would do the same in York, in Shrewsbury, in Birmingham and so on. We would, but we don’t have that political commitment to learning, and then we don’t have the political (maybe this is culture); We don’t have the political culture of deciding what the right thing is and then doing it year after year after year for 20 or 25 or 30 years and not chopping and changing when maybe one political party loses an election, because we don’t have proportional representation as well. We tend to have tribal politics, you know, where people sort of settle on an accepted view of what’s acceptable and what’s not acceptable. Again, if you talk to councillors in Sweden and in Germany and you’re talking to dozens of women between the ages of 20 and 40 and dozens of men, and they all come from different backgrounds and different ages, they tend to take things in a non-tribal way, because proportional representation gives them the opportunity to be on the council. Whereas that opportunity doesn’t exist largely in Britain.

Manda: Or in other places that don’t have PR like the U.S. and Canada.

John: Yeah, I’m not excusing the U.S. and Canada. I’ve also got a lot of experience of Australia, and they’ve got, in many ways, bigger problems than we have.

Manda: Alright, so we’re heading down to the wire. And in all that, wherever we get to, whenever I talk to anybody, we get to ‘we need fundamental political change and we should have had it 20 years ago’. But we are where we are. Have you thought… So you just discussed PR… And now I’m breaking out of the box of transport a bit, but it is clear we need political will in order to make the changes. I’m wondering how we could grow that political will from the ground up. So I’m thinking… Somebody emailed me last week, one of our listeners, who went on a course held by someone who did a previous podcast called ‘Trust the People’ and it taught them, online over time, ways of gathering people and finding consensus, working out what really matters. How to manage big groups, how to give people a sense that they’ve been heard and listened to, and how to build political consensus. And they are using those techniques in Shropshire, interestingly, where we both live to build consensus around our government’s delightful concept of just tipping raw sewage into the rivers because the sewage treatment chemicals come from Europe and we don’t want to talk to Europe anymore. So we can build political consensus from the ground up, and I’m wondering if we leave people with a structured idea of: if somebody listening to this, were to go and get the skills of creating local meetings, and then were to decide that local transport was the thing that they really wanted to work on, in order to build a mass of people so that when you stand for the local council and go, “OK, so I think twenty is plenty” On the council, I would stand for a 20 mile per hour limit.

Manda: I would be looking at free, fair public transport for everybody, and this is how it would work. I would be looking at a car free city centre and this is how it would work. I would be looking at the three zeros because they matter and they’re doable and this is how it would work. That you’ve got a population of people who wouldn’t just laugh and screw up your leaflet and vote for the Tories because that’s what they’ve always done. What else? What would you give these people as their baselines of conversation? What are the, I don’t know, the elevator speeches that you think are most important for people beginning conversations in their local communities to affect the change that we need?

John: I think that there are several things I would like to see happen. One is to provide a reliable non-party political source of information on what can be done and how easy it is to do and how well it works. And an idea about any costs that might be involved. And even though several people work along those lines nationally, I don’t think that there is a kind of a collective approach or something that would share knowledge and experience and information in that structured way. So I think people do need… It’s kind of confidence boosting, you know, we can do we can do these things. Secondly, and everything is interrelated, I’m a great believer in probably going back to my going to the movies in the 1950s. There’s no such thing as the US Fifth Cavalry to come and rescue us, right? We’re on our own. So basically, if I got a transport problem anywhere in rural Shropshire, I have to get together with my neighbours and be mates and the school PTA and and the local church group and the food bank and and and. And I have to say right, what we’re going to do is we’re going to find a mini bus or something and we’re going to run it. You know, we do have the potential in the British system to to organise community transport. So we can do things like that. I see a lot of progress in that way of thinking with, for example, renewable energy.

John: I don’t know of any but I’m sure they exist, by the way, in Shropshire. But I get information from Scotland as well about how people are supporting things like solar energy and wind power and other things so that it’s community owned and it’s community run and it supplies electricity to the community and the community are in charge. So you’re not you’re not selecting a large company, you know to where do I get my electricity from? You know you’re getting it from your own community co-operative. I’m in contact with the West Oxfordshire Community Transport Group, a brilliant group. It’s got a large internet presence – West Oxfordshire Community Transport. They run buses, they’re owned by the community, run by the community. And unlike our buses in Shropshire, any money they make doesn’t go to the back pocket of the private owner of the bus company. It goes to improve the bus services. Now that’s a very strange idea, isn’t it? You know, in other words, the fare revenue is all captured within that community. Now again, I think lots of people, lots of people think this way, but they need a bit of a morale boosting, confidence boosting to get it going. So I’d like to see a lot more community co-operative capacity building, if you like. And I think that works. And also the, back to your point, I think we need a much better campaign to get proportional representation. We’re not we’re not going to get much changed – I think basically England is… What did the Americans used to call this ‘rogue state’ or something, you know, when they were when they were worrying about Iran and Iraq and such things? We are a rogue state in that we have a defective malfunctioning, not fit for purpose political system that is destructive and makes things worse on a daily basis.

John: So what we need to do, and I’m criticising myself in this way, I need to think a bit less about transport and climate change, which is a bit difficult because I think about that all the time. I think a bit more about how we get proportional representation so that if I’m talking about how to improve transport in Shrewsbury, for example, I’m talking to a group of 10 or 15 women with children aged between 20 and 40 because I know I’m not picking on them for any sentimental reasons. I talk to these people in Sweden. They are councillors in Sweden. They get it. When I start talking, they say, Look, John, shut up. We know this.You know, we don’t need you to come from England to tell us this. We know this! So how can we work together to make Vision Zero work better? Or how can we get zero carbon? And related to that and I’m sure many people are aware of this. We have such a thing called the South Shropshire Climate Action Group, which I think is an absolutely brilliant example of… It’s not it’s not run by any layer of government. It’s not dominated by any particular experts. It’s a community initiative and people working together to produce a plan to get down to net zero carbon by 2030. Transport, housing, energy, land use, agriculture and so on. And we need more of that.

John: But that all comes back to proportional representation as well, because we now have done all that in south Shropshire, but we have yet to see a warm response. When I was a councillor many years ago, I was heavily criticised by my chief executive for demanding that we used our land to build council houses to provide more houses for people on low incomes. And he just said “no it wouldn’t work. It’s not convenient”. And I said, I don’t think he’ll mind me calling him by his name, Mark. I said, “Mark, have you ever said to anybody who came into your room, Wow, what a fantastic idea. We will do that!”. I said, “Have you ever said anything like that?” And he said, “You’re not being helpful. This meeting is over”. I said, “OK”. And that’s the problem, you see. We have lots of good ideas. But as Jim Hacker found out in ‘Yes Minister’ and ‘Yes Prime Minister’, when you come up with good ideas, the response is “here are 32 reasons why you can’t do it”. So we need much more community pressure and community presence. So I haven’t answered your question properly, but I’m trying every day to get better at answering your question.

Manda: You have answered it brilliantly. I have one last tiny question before we stop that’s been on my list from the start. When I talk to people locally here about do we have electric vehicles or not, and that’s always a big question, because we are in the middle of nowhere. There is no public transport. A number of people are holding out for hydrogen as being much better than electric vehicles. And I hear them on the rare earth…. I remember you saying if every car in Britain decided to be electric tomorrow, there isn’t enough rare earth in the entire planet to fit out the batteries. Is hydrogen a plausible way forward? And how soon can we think that it might come online?

John: No. It isn’t. When I was in Sweden, I had only by Zoom, I had a discussion with How do you pronounce it Scania? If you look around on your daily journeys, you’ll see lots of lorries and buses with the word Scania on them. They’re a global leader in making buses and lorries. Right? They pulled out of hydrogen totally, totally. They say it doesn’t work. It’s not feasible. It’s dangerous. It’s too expensive. The infrastructure to provide hydrogen is too expensive and it won’t be done. And we can get to the destination we want, which is zero carbon quite easily with non hydrogen interventions. So I talked to them at length about that. They they have over a thousand scientific staff working on this. That’s their view. I agree with their view. And also, where does that take us in terms of the bigger things: walking, cycling, public transport, city of short distances, planning things properly, you know? So I think that all this stuff around hydrogen is misleading, unfortunate and not correct.

Manda: Right? I will store that and use it next time we have that conversation. So we’ve come to the end of our John Whitelegg. Thank you so much for being so articulate and having solutions. So now, guys, our job is to go out into our communities, create the community action groups and begin to make the political movement happen so that we get all of the things that John has said. I thoroughly encourage you to read his book, Mobility. It’s beautifully written, clear and says quite a lot of this in ways that you can go and refer to when you need the arguments that you’re going to take to your local council. So, John, thank you so much.

John: Thank you.

Manda: And that is it for another week. Enormous thanks to John for being so articulate and for having so many good ideas and for having travelled to the places where those ideas are actually working. This is one of the things that I really enjoyed about talking to John. It’s not that he’s got ideas that are hypothetical. They are actually out there and actually working. And as is increasingly obvious from every single podcast that we do, the changes that we need to make are political. Not just in the UK, across the world. We need to be building the grassroots communities of people who get it and people who care. And I think everybody cares. It’s just that we haven’t got the ideas of what to do and where to go. And so what, increasingly, we are trying to do on this podcast is to give you the ideas of what you can do to give you agency, to give you facts, to give you the ideas that might really grab your imagination and become the thing that you run with. Power, food, transport, housing, community building, spirituality, whatever it is that makes your heart sing. Now is the time to begin to develop that and spread it as widely as you can in the local area. And ‘Trust the People’ is still running courses, if you want to have ideas of how you can undertake really effective community building with the people around you. So I’ll put a link to that in the show notes too.

Manda: And in the meantime, we will be talking to Jeremy Lent next week, I hope, author of The Web of Meaning.

You may also like these recent podcasts

Sit with the River, Breathe Sacred Smoke, Love with the World: Building a Bioregional world with Joe Brewer

How can Bioregionalism supplant the nation state as the natural unit of civilisation? Joe Brewer is living, breathing and teaching the ways we can work together with each other and the natural flows of water and life.

Solstice Meditation 2025 – Sun Stands Still – by Manda Scott

Here is a meditation for the shortest night of the year – the time when the sun stands still.

It doesn’t have to be at the moment of the solstice, it’s the connection that counts, the marking of the day. And you don’t have to limit yourself to one pass through – please feel free to explore this more deeply than one single iteration.

Thoughts from the Solstice Edge: Turning the Page on a Dying System with Manda Scott

As we head into the solstice- that moment when the sun stands still—whether you’re in the northern hemisphere where we have the longest day, or the southern, where it’s the longest night—this solstice feels like a moment of transformation.

Falling in Love with the Future – with author, musician, podcaster and futurenaut, Rob Hopkins

We need all 8 billion of us to Fall in Love with a Future we’d be proud to leave to the generations that come after us. So how do we do it?

STAY IN TOUCH

For a regular supply of ideas about humanity's next evolutionary step, insights into the thinking behind some of the podcasts, early updates on the guests we'll be having on the show - AND a free Water visualisation that will guide you through a deep immersion in water connection...sign up here.

(NB: This is a free newsletter - it's not joining up to the Membership! That's a nice, subtle pink button on the 'Join Us' page...)