#294 Dancing the Path of the Inner Warrior with Diarmuid Lyng of Wild Irish Retreats

We’re on the edge of a cliff and the way out is through – through the obfuscations and extractive values and downright lies of predatory capitalism. Through to authenticity, and integrity and finding language for how we can be who we really are, what our souls yearn to be. And that language is not always English.

This week’s guest, Diarmuid Lyng, speaks Irish – one of the older, indigenous languages of these islands. Listening to him is a genuinely fabulous experience in the truest sense of the word in that it lifts us to the place of myth and fable where our oldest stories are held, and we can reconnect with the bones of who we are so that we can carry our knowing forward into who we could yet be: who we will have to be, I’d say, if we’re going to make it through the current pinch point; and who we will love being.

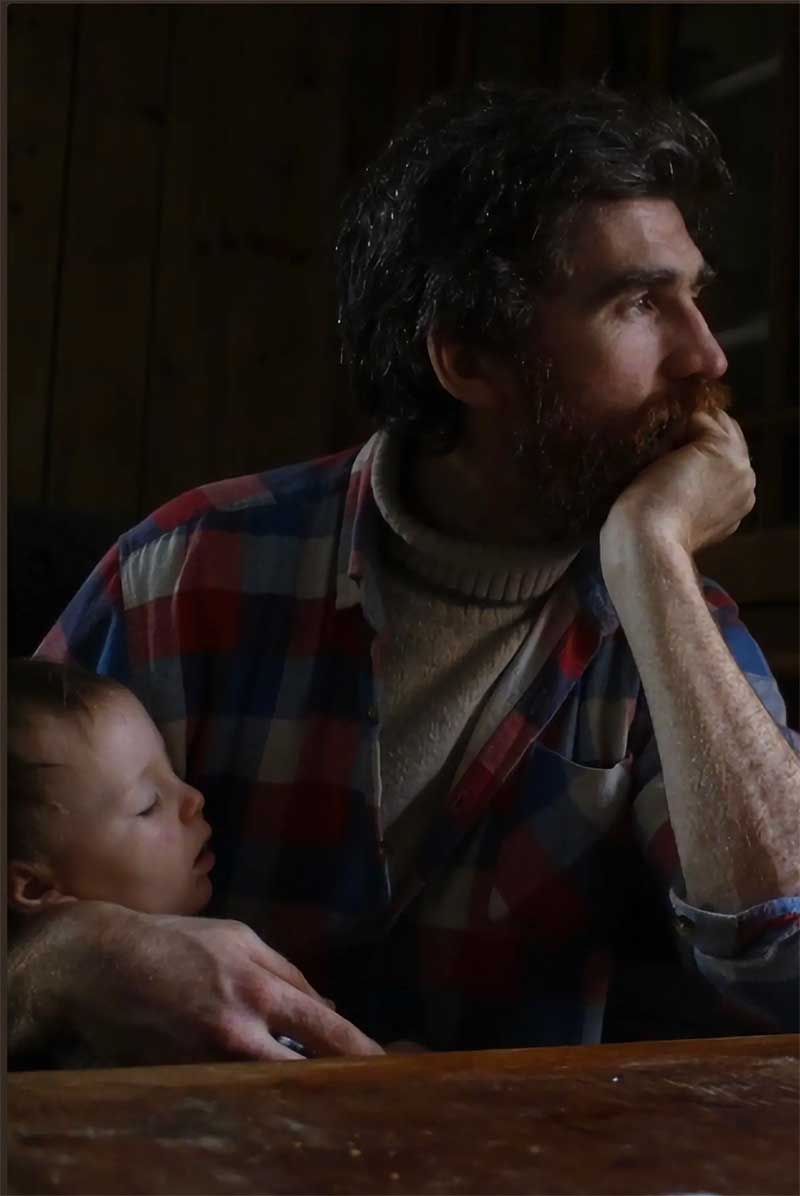

Diarmuid is co-owner of Wild Irish Retreats and Nature of Man. He is a former Wexford hurling captain and a host on the Irish Newstalk’s flagship sports programme ‘Off the Ball’. With Wild Irish Retreats he is part of a team that is focused on the rejuvenation of the Irish language in relation to nature reconnection. With Nature of Man he runs retreats and online programmes with men that creates a space for them to do their own internal spiritual work. He also takes teams/groups of all kinds to the woods for overnight camps that focus on connection; to self, teammate and place.

In all of this, Diarmuid is uncovering in people a previously hidden energy source that benefits the individual, the society and the web of life – and he does it with such authenticity, integrity and a really humble sense of what it is to be human in the world at this moment, that I found this whole conversation a genuinely magical experience. I hope you do too.

Episode #294

LINKS

What we offer

If you’d like to join us at Accidental Gods, we offer a membership where we endeavour to help you to connect fully with the living web of life.

If you’d like to join our next Gathering ‘Becoming a Good Ancestor’ (you don’t have to be a member) it’s on 6th July – details are here.

If you’d like to train more deeply in the contemporary shamanic work at Dreaming Awake, you’ll find us here.

If you’d like to explore the recordings from our last Thrutopia Writing Masterclass, the details are here.

In Conversation

Diarmuid: I think there’s a freedom of expression that’s born out of a depth of awareness and knowledge and respect for the world around us that is essential to the Irish spirit and the Irish psyche. I seek to embody those things just as I am, without care for what the results of that are. And the more I do it, the more people seem to respond and say, well, what is that? And I don’t want to answer the question because I don’t want to know what it is. I just want to be it.

Manda: Hey people, welcome to Accidental Gods, to the podcast where we still believe that another world is possible and that if we all work together, there is still time to lay the foundations for that future that we would be proud to leave to the generations that come after us. I’m Manda Scott, your host and fellow traveller in this journey into possibility. And if you’ve listened to this podcast, probably more than once, you will know that I believe we’re on the edge of a cliff, and the way out is through. Through the obfuscation and extractive values and downright lies of the death cult of predatory capitalism, through to authenticity and integrity and finding language for how we can be who we really are, what our souls yearn to be. And that language is not always English, Obviously. This week’s guest, Diarmuid Lyng, speaks Irish, one of the older indigenous languages of these islands. And listening to him speak is a genuinely fabulous experience in the truest sense of the word, in that it lifts us to the place of myth and fable, where our oldest stories are held, and we can reconnect with the bones of who we are, so that we can carry our knowing forward into who we could yet be. Who we will have to be, I think, if we are going to make it through the current pinch point; but also who we will love being.

Manda: Diarmuid is co-owner of Wild Irish Retreats and of Nature of Man. He is a former Wexford hurling captain and we will talk about that in a bit, and host on Irish Newstalk flagship sports programme Off the Ball. With wild Irish retreats he is part of a team that is focussed on the rejuvenation of the Irish language in relation to nature, reconnection. And then with the Nature of Man he runs retreats and online programs with men that create a space for them to do their own internal spiritual work. He also takes teams and groups of all kinds out into the woods for overnight camps that focus on connection, to self, team-mate and place. In all of this, Diarmuid is uncovering in people a previously hidden energy source that benefits the individual, the society and the web of life. And he is doing it with such authenticity and integrity and a really humble sense of what it is to be alive in the world at this moment. This feels to me like a truly magical conversation, and I hope that it lights you up in the way that it did me. So people of the podcast, please welcome Diarmuid Lyng of Wild Irish Retreats and Nature of Man.

Manda: Diarmuid Lyng, welcome to the Accidental Gods podcast. How are you and where are you on this amazing sunny day?

Diarmuid: I am in a forest in the north of Wexford, which is in the southeast of Ireland. I’m back in my home county and back to play. I came back last night to play a game of hurling, and I chased a 22 year old around the field for an hour, and I’m now lying down and I could be lying down for a little while into the evening, I’d say, because my body can’t respond in the way that it used to.

Manda: Yeah, you and me, we’re not 22 anymore eh?

Diarmuid: Yeah, but it brings me, like it’s a lovely thing, Manda where I found this, like when I played the game when I was younger, I played for professional level, and I got very much caught up in the ego of it and the kind of win it all cost side of it. And I suppose an output orientation in the game. And now that I’ve come back with a bit of sense, I can flow in the game an awful lot more, and I feel like more of a kind of a ninja. Like I can see things happening and I can influence the game in ways that I couldn’t when I was younger. And so it’s very, very joyful. It’s a very joyful experience, you know? So I don’t know, I wonder sometimes yearwhat am I doing these days running around after 22 olds? But in the moment of it, it’s a real blissful experience, you know?

Manda: Yes. So all the things that you and I considered we might be heading are now out the window, because we’re going to have to explain to the majority of our audience what hurling is. And then I’d really be interested in that as a metaphor for everything else. Because a lot of our culture is on that ego driven, results driven track. And how does it feel to come back with a completely different view? But explain a little bit about hurling.

Diarmuid: Yeah, I mean, this could be the whole conversation in many respects and I know you’ll absolutely love aspects of it. I mean, hurling originated in Once Upon a Time time, time, as John Moriarty would call it, in Ireland. Like the point of where myth meets history, that that’s where it goes back into. Now, it would be a story, as happens to the great folktales that are relegated to a children’s story and so we treat it as so. But as I understand it, the archetypal warrior of Ireland was a man named Cú Chulainn. And so Cú Chulainn was a hurler by nature, I suppose. And I suppose I felt in the moments of awareness that I had where I was playing, like where I was on my little adventure up to Croke Park, this massive stadium in Dublin, to play in front of 60-70,000 people, that I was on this journey that Cú Chulainn went on as a young fella, as Sétanta, when he went up to Conchobar mac Nessa of the Red Branch Knights, and he was throwing his spear and hitting his ball and throwing his hurl, and he was catching all three. And that was how he shortened the journey for himself.

Diarmuid: And I could feel at times that that was the arising of the archetypal energy and that’s where the great story is lost, is that we relegate it to the children’s story. But actually we can assume the the spirit of Cú Chulainn, that’s what we’re doing, we’re kind of almost channelling that. Now I wouldn’t be a channel or I’m not getting downloads from the world and the way other people are, but certainly that was my closest experience of it. That I would be on that same journey and then I would feel this kind of, you can obviously define it as adrenaline if you wanted to look at the scientific side. But you were also coming into the spirit of that, where you kind of felt these superhuman qualities, where things would slow down and where you would have strength. Like people could break a 35 inch piece of ash off your hand and you wouldn’t even feel it. And if you were to do that to me now here, I mean, I’d be, you know, softer than most.

Manda: It would break things.

Diarmuid: But in that, when you were spirited, it just didn’t register in the same way. So hurling has been played for hundreds and hundreds of years, thousands of years here. Some of the earliest games would have been recorded around the sixth and seventh century. As part of Brehon lore, they would have had a very detailed, almost insurance policy where if you killed somebody, you would have to give them two cows and take care of their farm. If you broke their arm, you would have to go and farm till they were right. You know, there were rules for if certain things happened. And it’s a tough game, you know, a lot tougher in those days, obviously. But that was played and it was played between towns. And so if I’m in Gorey here and we were playing against Wexford, the ball would start between Wexford and Gorey, halfway, and you had to get the ball to their town. And so they defended their town. So in the 1880s then that was more formalised. The Dublin Metropolitans kind of left Dublin and went around Ireland and toured this game, that created more order. It brought it into a 160 metre long field, similar to American football. You know, the rules came in and they organised it and the lads in the country were like, hang on a second, that’s not hard at all, it’s too soft and there’s free’s for everything and why are we doing all this? But eventually it caught on and it led to the formation of the Gaelic Athletic Association to manage that game. And it became a bit of a hotbed then for, like, at that stage the move for independence was getting stronger in Ireland.

Diarmuid: There was a Celtic revival at the time, and in the 1880s a lot of the young fellas that were coming in to hurling teams were kind of being trained for battle as much as they were being trained for hurling matches. And then that would have intensified in 1916, in our rebellion here. And in 1921 as well. Those teams already existed of young men who were physically capable. So it’s very much intertwined with our history at all levels. And that’s not lost on me when I play the game now, although I feel like I did lose that connection to it when I was at the height of my career, in the human story sense of things, you know. And then that comes right up to this day, where the ash dieback, the ash, the hurls are made from ash, and the ash dieback is just coming into Ireland now and beginning to obliterate our beautiful ash tree. And I think if ever there was a possibility this this tree has given us this game. And I think that where we needed warriors in 1920 for independence, we now need eco warriors of a kind to say, well, look, let’s take the resistant strains of dieback. We need an army of planters, we need land in the GAA clubs. And it can all happen symbiotically, where the disease is also the medicine, because the game moves from the world of entertainment back into its roots, which is in the tree, you know. So there’s the whole. There’s plenty of places to go from there.

Manda: There is.

Diarmuid: Heading down to the game last night and I’m playing an old Wexford song from 1798. My area in Wexford fought a battle in 1798 against the English, where the rest of the country didn’t fight and we did. And it’s a source of great pride. And there’s this lovely song, Kelly the boy from Killane, sang by The Dubliners. And I’m going down to the match and I’m singing that, and I’m invoking the spirit of Wexford and the spirit of hurling, going down into the game. And it’s really beautiful, you know.

Manda: Yeah. Gosh, you’re right, there’s so many different ways to go. I still think we’re not quite clear what hurling actually is. I think let’s do that because I think people need to have something in their head. And then we’ll go along the many branches that you have opened. But what do you actually do besides breaking out on each other’s hands?

Diarmuid: So if you think about soccer or American football, it has a similar structure. There’s 15 on 15. It’s different in the sense the players mark each other in different positions. You have a small leather ball about the size of a cupped hand, and you have the ash sticks, and the aim is to score in the other person’s goal, akin to trying to get it into their village originally. And so there’s a set of rules. You can take four steps with the ball, you can solo, you balance the hurling ball on the hurl. There are a variety of rules, but I would say the best thing that you could possibly do if you don’t know what hurling is, it’s very difficult to paint the vivid picture, but there are videos on YouTube. If you just type in hurling, you’ll see Croke Park, you’ll see 80,000 people.

Manda: I will find some. Put them in the show notes. Send me the good ones and I’ll put them in the show notes.

Diarmuid: Okay. I send you my highlight reel.

Manda: Yes do! That would be fantastic. Because it feels a little bit like ice hockey. And I’m wondering if Irish people being deported by the English to Canada took the concept of hurling and went, well, we’ve got a lot of frozen water and we could change it because it’s got that same… it feels to me that ice hockey in Canada has that same sense of, this is who we are as a nation. And you’re aiming a little thing at goalposts and people try to stop you and the intricacies of the game I’m sure are different, but the sense of pride and the warrior ship feels similar.

Diarmuid: Mm. The spirit of the game, I would say, is very, very similar. The professionalisation of hockey has obviously changed that because you’re not representing your place as much? And that’s a real thing, you know, like a sense of place is a real thing. Whereas we don’t have those trades; you don’t represent other places you represent your people. But as far as I know, and I’m assuming maybe the Canadian scholars may have a different story because it’s interpretive endeavour to some degree. But the story is, is that ice hockey originated in the Irish who went to Canada and brought this game, and there was a corruption of that. But look, it’s a stick and a puck and a ball.

Manda: And a goal.

Diarmuid: Very, very simple that would probably come up everywhere as well. You know, similar type of games.

Manda: Yes. The Maya had something similar. And then obviously there’s hockey. I am remembering back to when I was doing a veterinary training in Glasgow many, many moons ago, and we had people from the north and of the south in our year, which caused a degree of friction. And it seemed to me that the hurling then, they seemed to me to be going on to the pitch with the explicit aim of injuring people. That and rugby. And I’m thinking now that will not be the same.

Diarmuid: That is an aspect of the game. And I find it a very interesting aspect, particularly with the work that I do now and when I play games. Like I’ve incorporated hurling into the retreats, to get fellas out playing, you know, and it’s a very healing experience for many of them, because they fell out with the game in different levels. Maybe they’re musicians and they were run out of the club because they wore red pants one day at the training. And the fellas who hold the dressing room wouldn’t appreciate that because they want the blue jeans and the Wrangler shirt or, you know. I’m speaking very generally in a sense. But what people bring onto the field I find very interesting. And I can see sometimes in facilitated spaces, I don’t pick up a huge amount, as much as other facilitators I would say. But when they’re hurling, I can see very clearly what’s happening in terms of their body language, because you can see how they’re going in. And so I would say to them, you know, like notice. Competitiveness is fine. I think competitiveness is an innate human instinct to some degree. It’s not the only one, but it’s certainly in us. Excessive competitiveness because of the damage that your father did in your relationship when you were younger, of the roles that were put on you by the adults of the club, or your own inability to follow your own dreams, the courage to follow your own path in life; that’s not welcome.

Diarmuid: And so if I see that, I’m going to pull it up and say, this is what this is, and it’s a kind of a hook to work with for somebody. So if there’s any element of somebody coming in to injure, which can be part of the game, in my game I can control that. In the game itself, yeah, that’s how injuries happen and it’s not in the spirit of the game. And it’s a really interesting thing and a really beautiful thing as well; there’s the game, there’s the individualisation within the game, there’s the team sense, there’s the representation of place and there’s the inner dynamics. And we get very caught up in those sometimes. We want to kill the fellas down the road, we want to beat them, we want to perform well. We want to get the goal and bring home the cup or whatever. But the most successful managers are people who are involved in the game here, speak about the game as separate to all of that. So you interact with the game honestly, with integrity. The game is its own thing and you have to interact with it with integrity. If you do that, the game will respond to you, and if you don’t, the game will reject you. And so when people come in to injure, they don’t receive the bounty of the game; they just never do and they’ll never know that loss.

Manda: Because the integrity is just not there.

Diarmuid: Absolutely.

Manda: Gosh, so many ways I want to go. So one of them, and this is still a bell ringing in my head and I would like to really come back to integrity and values and what is the value base of who we are as humanity. But you mentioned Cú Chulainn, who is a huge hero of mine. And I think for people who are not familiar with Irish lore, let’s unpick that a little. But the thing that always struck me, one of the many things, but when I was writing the Boudicca books, I was aware from a number of things, particularly Caesar’s writing, that being a warrior was not a gender specific thing in the pre-Roman world. And Cú Chulainn, when he needs really to train, he goes to a warrior school run by a woman, whose name is Scáthach . Is that how it is pronounced?

Diarmuid: I think that’s good enough. Yeah.

Manda: How would you actually say it?

Diarmuid: No, that’s how I would say it too.

Manda: All right. And it’s not saying in the stories that this was really strange that a woman should run this school, because that’s where you went to train because you needed to be the best. And she was the best trainer of warriors in all of Ireland at that time. And that seemed to me, when people are going, yes, but of course the women were not fighting. And your evidence for that is what exactly? And look here we have this and it’s obviously started off as an oral tale and moved into being written. And that seems to me as solid as anything else. I once had a very interesting conversation with someone who said, but we have no evidence that Boudicca existed. And I went, well, there is a lot more evidence than there is that Christ existed, and you’re not questioning that. So let’s just go with this, shall we? Shuts down the conversation relatively fast. But tell us a little bit more about your sense of what it is to bring the spirit of Cú Chulainn into the 21st century, because I am feeling that sense of what it is to be an inner warrior as a gender neutral thing; but for you, you’re working primarily with young men. Is there a women’s hurling league?

Diarmuid: There is. Yeah. It’s called camógaíocht (Camogie). Yeah. Yeah.

Manda: Cracking! Okay. All right. There we go. How do you open the doors for people? This is a long question, but it feels to me that warriorhood, warriorship, whatever we call it, has been tainted by the whole death culture of predatory capitalism. It’s been turned into something vicious and toxic. And actually, inherent to how we will work forward into something different, is refashioning what it is to be a warrior. Partly because that’s going to take a lot of inner work and the inner work is what lays the foundations for everything else.

Diarmuid: So I think Scáthach, I would say with that, like there’s an old phrase here ‘never give a man a sword until you first teach him how to dance’. And so that inner work, I think, represents the more intuitive feminine work. Now, if we separate out, obviously, like a matriarchal society, which I suspect Ireland was more of, and possibly the British Isles at that time, because there was more of an awareness and a respect for the world of intuition, and maybe more necessity for it. It seems that having a woman as the head of that school was, you know, that invitation into the inner warrior first. I mean, it was a very interesting thing, I don’t know if you’ve come across Rónán Ó Snodaigh’s music here? An incredible Irish musician in a band called Kila, and he’s basically been going around the country lighting fires under young fella’s behinds for the guts of 30 years. And kind of demanding that they step into themselves in a kind of a powerful way, you know, and he’s done it through the Irish language and remained committed to it in his music. But he was talking about a fight that took place recently between an MMA artist in China and an old tai chi master. And before everybody had different opinions, you know, the spirited were obviously thinking, well, the Tai Chi masters are just going to use the force of his hand to end the MMA fella, and that’s going to be it. And the MMA lads were like…

Manda: That’s not how it usually works.

Diarmuid: That’s not. I don’t want to ruin the story, but that didn’t work for sure, because the MMA artist and they were all saying, look just go easy. Don’t kill him. Like, we don’t want to kill this man. He’s an old man, you know. And so the fight lasted five seconds, and the MMA artist had the man on the ground, and that was the end of that.

Manda: Yeah, because once you get them down, MMA always win.

Diarmuid: That’s how it was always going to be. And I was talking to Rónán about this. And what Rónán said to me was a very enlightening answer in relation to what you’re talking about. Which was, of course he did, because he trains the external warrior but the Tai Chi master trains the internal warrior, and there they’re two different things. And we have Conor McGregor now as this representation of the outer warrior, which is those aspects of violence that suit the industrial military complex or that individuated version of the world. Whereas I think what we’re probably trying to embody more at the moment is the inner knowing first and cultivating an inner power and bringing that in. And really, I mean, I don’t know where it’s going to go in Europe at the moment. Nor do I need to. But those battles take place very frequently throughout the day, more in terms of in the conversations you have and how you show up in the conversations that you have, in the work that you do and why you do the work that you do. That’s where the internal warrior I think really earns it’s crust, you know, like in our modern world we’re not going on cattle raids up the country anymore, do you know? So it’s really in just how we show up and the development of that inner warrior ship is, is more how we show up. How we show up in relationship to our spouse, how we show up in relationship to our traumas and our inner child. How we show up for our own children and then how we how we show up in the world in terms of building the thing that we can see is wrong and we can swim in what’s wrong, or we can create the thing that we feel is a medicine for what’s wrong, you know. So I could bring that back to other places maybe, but that’s where I’m at for the minute.

Manda: I’m curious where you’d bring it back. So the things that sparked for me there, particularly the inner work, to look a little bit more depth at how you approach that and how you help people to understand. Because I’m pretty old now, and it’s taken many decades of therapy to get to the point where I have the insight, the understanding and the courage, and to be fair, the bandwidth and the space in my life to actually really look at the bits that are broken and not have to hurl them out and project them on other people. And it’s hard. And offered distractions, I think if I were not teaching this, I would take the distractions. There’s something about the integrity of teaching, as I have to bring my best integrity to this, I have got to do this work. Which doubtless, frankly, is why I’m teaching. We teach best what we most need to learn. But younger people caught up in the maelstrom of the military industrial complex, it’s horrible. How are you helping them to find that inner spaciousness to be able to find the courage, the warrior courage, to work with the parts of us that are most broken?

Diarmuid: The first thing that I’m very keen to do in those situations, and when I speak about it, is to distance myself from any form of knowing of anybody else’s journey. I want to avoid at all stages any form of guru style work. There is a lovely image created in my head by the Irish mystic John Moriarty, who talks about the boatman from Indian philosophy, who takes the seeker from their island that they’re on, which is their level of consciousness, we’ll say, that they’re at at that time. And he knows where the island is that they need to get to. He’s been there, so he knows where it is. And he brings them across the threshold to this island. But what happens on the journey over, and I’ve seen that happening, it was happening to me early on, was that people start to look at you as the boat driver and they’re like, oh, because you know where you’re going, you must be the thing. There’s this connection that’s made, and there’s this idealisation. And that would lead to a very deep connection in the moment, because they’re at this time of just cracking through something. And now I’m associated with that cracking through.

Diarmuid: And I found that the relationships very often fell away very quickly. And I was left a little bit desolate in a sense, because maybe I was believing them a little bit, you know. And so I realised that the harshness of that lesson reminded me with the image that no, I have to create the distance when they’re on the boat. It’s over there. I just happen to know where it is and so I’m happy to bring you there, and that’s what I’m doing. And so that frees me up to feel at the retreats in particular, or when I work really anywhere with anybody, is I want to create the space and the conditions that they have enough time with no easy get outs, to still themselves long enough to hear their own internal voice. Possibly for the first time since they were children. And then once they begin to hear it, to begin to trust it. And so it’s really just, I almost say to people like, look you paid money to come on the retreat, that’s for the retreat centre, it’s for the food. Okay, we have a couple of practices that we know are beneficial. It’s just the breath. It’s simple stuff. You can call it whatever levels of breathwork you want. It doesn’t matter. It’s just breathing. We’re going to go out and play. We’re going to sit on the mat. We’re going to share, we’re going to do these things and it’s up to you.

Diarmuid: You can bluff your way through them all you want, that’s none of our business. Our business is we believe that if you treat it sincerely, it doesn’t have to be heavy and intense and it’s joyful and it’s expansive as well. But if you treat it sincerely, it seems from everybody else who’s come on the courses and their feedback that they have reconnected to their inner wildman, they’ve reconnected to their inner sage, they’ve reconnected to something in themselves. And we get this most beautifully back from some of the wives who would get in touch afterwards, and they would say, thank you for bringing my man back. The man that I married or whatever. So, yeah, that’s where I’m at with it. And I think that lets me off the hook a little bit. And I can be worried about that at times, in terms of like I’ve got three small kids; a year, four and seven. We’re in the process of trying to build a retreat centre, like buying a house, raising money. There was a crowdfund, all of this stuff, as our vision and our offering to the world.

Diarmuid: And so the inner work that I had done maybe a few years ago when I went out into the wild and just really went into it, I’m not as engaged and as active in that. And it’s often actually listening to John Moriarty; I discovered John when I was in the wilderness, and everybody else was saying, come back into society. And John was saying, could you go further? Are you far enough? Do you need to go further? And I could really feel the depths of his message at that time. And sometimes now when I listen to that, when I get a half an hour to myself, it doesn’t land as deeply I notice, because I’m not as in touch with depths as I was in that time. And I think that’s just because I’m also trying to navigate the world, the physical world. Get money into the bank. Talk to people. Build community. Build connection. You know, like, maintain a lot of relationships and a lot of dynamics and also keep my own self sane in all of that. And so yeah, so in terms of the teaching and maintaining that integrity, it’s probably my primary concern is that I’m not giving that quite enough time. But it’s still present and it’s working.

Manda: Mm. Yes. It feels very present. And being a father to three young children is a very time consuming thing. I think that’s why in the indigenous cultures that I’m aware of, the elders tend to be parenting the children because the people in their middle years are the people making life keep going. But it gives a lot more space to be doing the inner work. And we still have this bizarre culture where two people raise their kids instead of the entire village raising their kids. So, okay, learning to trust. Partly I’m coming to this off the back of four days of teaching, and it seems to me that people who come to us, let’s make the assumption, it may not be the case for you, but they tend to be a self-selecting group who are at least aware the inner world exists. And they have a lot of ideas about what that’s going to be. And part of what we need to do is bring them from head down into heart mind and body mind. I’m loving the idea of hurling; full on body mind. Not so much head mind. You’re in the energy. It’s like you’re part of the murmuration of the starlings. And if you can have full integrity of that, the whole place is going to move, like starlings move. That feels absolutely extraordinary. And we need those things that are incontrovertible. I think because our Western culture, which has been going a very long time, I’d like to explore cattle raiding and what might have happened before.

Manda: But we live in a highly competitive, head based, self judging culture, and we’re trained to that from very small. And yet we know this is not where we need to be. And helping people to move. It seems to me that once in a while there’s a very clear yes, this is totally right. I’m balanced on the knife edge, clarity, black and white. But for most people, there’s a lot of shades of grey. Of I’m beginning to step into a sense of myself, I’m beginning to find authenticity, I’m beginning to find the inner knowing that I can trust. And I wonder, how do you help the people that you’re with on your retreats and your hurling games and everything else, distinguish between all the parts of us that either want to tell us that we’re here… And as a person leading the circle, there’s the ‘I would encourage you to go deeper because genuinely, I think that’s your head mind’. I wouldn’t say it like that, but the energy going through me would be this person, I need to help them go deeper inside, because they’re still generating ideas of where they think they’re going. And one of the things that it seems to me, the boatman metaphor was beautiful but, and this may be because I’m quite a long way along a neurodiverse spectrum, but I learn by pattern matching.

Manda: I find the person who does what I want to do the best that I have ever seen it and I now would say; I used to say I watched them and copy, but now I would say I bring my energy into alignment with theirs and I see what it feels like. And yet for the MMA, which for those who don’t know, is mixed martial arts evolved in Brazil. MMA guys basically are going to win anything because exactly as you said, they’re outer; tai chi is inner. If I were really wanting to know who I am, I would go to the Tai Chi master. And even if I was just sitting in the presence while they were doing it, I would feel that alignment. And it isn’t that I necessarily think they’re the boatmen, but my energy space understands more of what it is to be inwardly aligned. So I’m wondering, given that we don’t want people to think that we’re gurus, because that is not a useful thing. All the same, we’re doing our best to model what it is to have integrity and to be grounded and to have that sense of, I would say, connection to the web of life. So that that is providing the energetic space. How does that land with you and where would you take it.

Diarmuid: Um. There’s two primary things coming up in it I suppose. I’m probably doing myself a little disservice in the sense that when we are in that space, I very much come into my physical body and I’m kind of scanning the room and seeing where the blocks are. And I’m feeling those blocks in both observation and feeling. And I’ll generally go and connect with wherever I feel the block is. And I don’t feel particularly limited by the modern world in that, in this, if I need to lie down beside somebody, if I need to put my hand on their heart, if I need to just rub their feet or, you know, whatever; when I tune into them and I feel okay, they’re just they’re in the breakthrough. I can feel it. They just need a little bit of warmth on their heart and that’s going to go. It’s going to go and they’re going to come in to it. Or it might be like on the last retreat, there was a fella, and this was from the human story. But I knew he ran five companies and employed a thousand people and was go, go, go, go. And last bringing up his children and all of those things that come with that world. And I just looked at him and he looked at me and I thanked him for supporting the lives of all of those people. And I wasn’t saying it out of I think this is what the facilitator should do. I just really felt it towards him; Jesus, fair play to you, you know. And it was like nobody ever said fair play to him, because that was the gates broke. And so in the sweat lodge, which, you know, maybe we’ll get on to as well; like in the sweat lodge at times, if there’s somebody who really goes into something where they’re really releasing, they could be bawling and crying. And these could be 15 men sitting beside each other and you’ve got one really going. And I’ll go in with them and very often I’ll be crying too, because I’m just, I want to be in it with them. I just feel like that’s my support for them. And very often at that stage, I’ll throw out the book on what should be done or shouldn’t be done and just go in with them. And I don’t know if any of this is like, I wonder, because I feel you’re much further along on the journey, like.

Manda: Oh dear, no.

Diarmuid: I don’t know if any of that is right, but it feels in it all, it feels like it’s just it’s own thing. I don’t even want to put words on what I think it is. It’s just it’s own thing, you know? Yeah, so that’s that part of it. I can’t remember the question now in terms of the second part.

Manda: No, no, I think you’ve taken it a long way. It was how do you help people to feel authenticity? And the answer is you were there with them. It’s because I’m guessing that you get to that headspace.

Diarmuid: So that’s the other point. Yeah. It’s and again, I kind of I fracture some facilitation rules here in the sense that I will speak and create the space. And I would encourage people to not be telling their own stories, for example, in a circle in their heads in preparation for time coming where they have the talking stick and encourage them to listen, because that brings much more out of when you’re intently listened to, you become much more articulate and direct what you’re speaking. And so I’ll set those tones, but then when it comes to my share, I will be who I am. I will carry in my brokenness, or carry in my beauty or carry in whatever it is to be carried in, because instead of at that point putting myself up on a level, I believe in really going in with them and saying, remember, I’m also just a human being with you, and I’m subject to all of the same things. And in one sense that’s again a little bit of a get out clause, but in another sense, what I’m really saying to them is I’m not a modeller, I’m just who I am, and I’m going to be authentically who I am, and I’m not going to apologise for it. And I don’t care if some book says that I shouldn’t do it. This is who I am, and this is what I’m asking of you; who are you? So it’s it’s the modelling of it, I suppose, in just showing up authentically as yourself. I think is a great way.

Manda: Because what else can we do? I mean, just experiencing you here now, you feel absolutely authentic. This is I am seeing you, and we’re not necessarily bringing up every trauma but this is human being to human being, human heart to human heart. It’s real. And so much of our current culture teaches people not only how to mask, but that masking is essential because we have to play the game, and the game is not about being real. Because if you’re real, everything falls apart. And just modelling authenticity I think is huge.

Diarmuid: This has come up and it’s such a really good point. This came up on the last one where I really realised that, you know, we work with people of varying, varieties of different traumas or whatever. But one fella said that, and Jesus it broke my heart when he said it. He talked about having been initiated into the sexual world at the age of eight.

Manda: The rest of us call that rape.

Diarmuid: So, yeah. But such a way to say it and it really went through me, the way that he put it. But in working with those people. Yeah, I lost my thread there now because I felt that…

Manda: It was about being authentic and not being masked and being required to be masked.

Diarmuid: So what he said and what they said was the trauma of the moment was its own trauma, but they felt, you know what? I can actually kind of deal with that. But I’m retraumatized by society’s unwillingness to acknowledge that experience. I can’t speak about it. If I do, I get labelled, shunned. So he said, where the real trauma is, is that nobody will actually speak as though that happened, that that’s just real.

Manda: Exactly.

Diarmuid: And so that’s what I try to. I don’t want to be in a retreat, a financial, a house, a place, you know, all the labels. I’m like, no, no, we’re human beings. Whatever is happening for you now. And they say sometimes, there’s a big typical Irish archetype coming to us at the moment; big fellas with a lot trapped. And they’re saying if I go, you’re going to have to cancel this retreat. Like I’m going to wreck this place if I let go. I’m going to wreck this place. And we’re like, bring it on. Like, that’s why we’re here. Bring. It. On. And when they do break through then and they just see, oh, my story, every aspect of my story is welcome, finally, somewhere it’s welcome. I’m saying I don’t want this to be a retreat I want this to be the way we live. I don’t see why we just can’t live in that, like, this is real. Are you able for the truth? Or what? You can play a game? You know, people say that to us with the retreat centre. Just play the game, you know, you sell it. Just play the game. And I’m like, well, I don’t want to play the game because I’m looking at what’s happening in the world and that’s the game, that’s what it is. That’s the natural endpoint of that game, and I don’t want anything to do with it.

Diarmuid: I want to just trust. I don’t know where it’s going. I don’t know if it’s acceptable. I spend a long time in my life thinking everything that I thought wasn’t particularly acceptable, and I couldn’t welcome myself into my own moment. But now I’m like, well, look, I’m all in. I’m all in. Just all in on it. I don’t know if it’s a better way. It’s a better way, I see. And if it’s reflected back to me over time that this is a better way, we have something. If it’s reflected that it’s not, then I have to revise my way. You know. But at the moment, I’m totally trusting what feels like a golden thread that’s just been laid out in front of us. And I’m not seeking to control. And that’s all in there.

Manda: Yeah. Glorious. And again, so many threads. I want to explore your vision for your retreat centre. Okay. Let’s do that, because where I’m wanting that to end up and if we end up with two branches that’s fine. We live in a world where we’re told ‘just play the game’. And that is taking the bus off the edge of the cliff. We are in the middle of the sixth mass extinction because people play the game. And it seems to me that if we came back to your ground value of integrity and I would add compassion and generosity of spirit, and I think these three work together.

Diarmuid: Oh, generosity of spirit I just love that Manda. I haven’t heard anybody else talk about generosity of spirit as a core belief, as a core structure. And I find I love with my bones I love when I meet generosity of spirit.

Manda: Yeah. Thank you. Thank you. I sat with the fire at winter solstice, it was before lockdown, before Covid, I can’t remember when. And the instruction for that year; this has been the year gone, what do you need for me in the year to come? And the fire said you have to find generosity of spirit. And that’s a lifelong task, I think. Yeah it’s not what we’re domesticated into, but I think it’ll carry us forward. So with that as our base, let’s play hypothetical. Because we’re existing in the death cult of predatory capitalism, you’re not going to be able to build a retreat without finding some money from somewhere and there is no such thing as clean money. It just doesn’t exist because money evolves out of violence. So there’s no non-violent money. But we can try and find the least violent money available and then build somewhere that, I have a kind of sense that everything is fractal, and that there are critical masses and tipping points that exist at many different layers. And if you in, I’m guessing it’s in Wexford, created, then you could change the energy of the whole of Ireland. And if Ireland changes, Ireland could change the energy of the whole of Western Europe and all of Western Europe changes then that could change the whole of the Northern Hemisphere. And very soon we’re at a whole different way of the world being that is not predicated on predatory capitalism. Talk me through what it would feel like if we were doing that.

Diarmuid: It’s a terrifying concept in regard to the amount of different strands that exist that point to the very real possibility of that. Because also, you know, I have to build this thing without much money, let’s say, I’m not getting a loan for a million to build a retreat centre that’s high spec and perfect. It’s going to be perfectly imperfect. And I have a lot to learn on that journey. But I would say at first we get drawn into the the retreat centre, this idea that there’s a retreat centre. Now, just to give, I suppose, a bit of context. The men’s work I would do separately. My work with Siobhan, my wife, has been around Irish language reconnection and that was kind of what it started off as. But very quickly, the spiritual aspect came through because it was just so present in all aspects of the language. And once the spiritual connection came through, the next step backwards in that was the fact that the language is rooted in nature, like very foundationally in the trees.

Diarmuid: That’s like the origins, the ogham writing, the alphabet, this comes out of the trees and the way we held the trees at that time. And so we were in nature and we were in spirituality, and we were in play with hurling, obviously. And we were out in the sea and we were in ritual with sweat lodge or whatever ritual Siobahn might come up with on a day where one one might be needed. Myself and Siobhan met in West Kerry. Now, you know from the geography of Ireland, Irish Celtic culture in its essence stayed most alive on the fringes of the western seaboard because the land wasn’t as valuable. They had thinned out by the time they got there.

Manda: The English, frankly, didn’t want to go that far.

Diarmuid: They didn’t want to go that far. And so we went out there and that’s where we met. And we had a seven year love story there where we began to build a family and build very loosely a business and our dream was just kind of taking shape together in terms of what we could do. So we’re bringing that now. We’ve been going around the country doing that. And that’s very difficult with a young family. And also we’ve got 15 sheepskins and we’ve got woollen blankets and we’ve got trinkets and we’ve got, you know, we’re packing the kitchen sink and it’s all off on the road. And that takes a huge outlay of energy. And so the dream has been to find a place. And we were handed this place for like €400 a month in South Kilkenny. And as we looked around we were like, okay, there’s stables there, that could be some accommodation. There’s a long shade that’s like a lovely long table dining hall. There’s a big barn at the back; that’s a venue for our musicians, for our workshops, for, you know, whatever. And then there’s barriers around the sides, with fallen drystone walls and drystone walling and you know that can all be done. And there’s a beautiful river at the very bottom of the site as well, that south east facing sloped down into it. So it’s a gorgeous place and potentially with all of that work done, a home. A home for Wild Irish, I should say, and our work. But what I really want to avoid is falling into the trap of thinking when it’s done, I will… When it’s done, we will… So now on Thursday, Peia and Rónán Ó Snodaigh and Candlelit Tales will do a fundraising gig at this Kell’s Priory, which I really want to talk to you about. But anyway, I am showing up as I’m going to MC it. I mean, I haven’t discussed this with anybody, but I’m going to MC it, and what I’ve already organised is there’s a woman who came from India with mantra singing with the harmonium, and she translated that into Irish language chants and mantras. And so I want her to play first, and I want all the crowd to sing those mantras. I don’t want it to be a gig.

Diarmuid: I don’t want it to be we’re coming to consume something. I want to come and let’s all, maybe you’re going to make this sound, you’re going to make this sound, let’s sing the four directions, let’s see what comes out of us. Like let’s inhabit our voices. Let’s make something that doesn’t have to be what it says on the tin. It’s not that. It can be something different and we can all take part in this unfolding. And so it’s a lot less about a physical place and whether we build this or we build that. It’s what we embody of the spirit, of what we believe to be the core of why we’re doing what we’re doing. That connection and that aliveness and that awareness of the unseen, the awareness of the seen. The nature based seen. And the awareness of what’s happening internally to drive us away from those things. I want to embody that in this conversation. I want to embody it on Thursday night. I want to embody it when the person who’s coming to my house tomorrow; I’m going to dig a grave for them and put Athair thalún in, which is the masculine plant of Ireland, Yarrow. Athair thalún literally means father of the land and one of the families of the rose. And dig a pit and put those at the base. And she’s going to lie in that grave for maybe 4 or 5 hours I’m not sure. And I want it to be in that, too. So do you know what I mean? It’s more to live it. Not for it to become a product where I take it out of my box now, this is what we’re doing here. And it’s like how do you do it? How do you build it? You know, I think how you build it is you’re willing to put a call out and say, we need help. And God forbid you need help in this day and age. God forbid you need help. There’s something wrong with you if you need help. Anytime if you ask me, Manda Scott, if you ask me anything to do, can you do something for me? I’d be like, oh my God, I’d be telling people, I’ve got this chance to help Manda Scott, you know, I’ve got this thing like I get to do.

Manda: Well, likewise.

Diarmuid: You know, and it’s the same when anybody asks us a question. We’re like, oh, God, finally I have a purpose. I have something I’m going to do, this thing for you and I can’t wait to do it. And we think when we’re the asker, oh, I’m offending somebody by asking them. And when we went out, we launched a fundraising campaign of which we raised about 50,000. It’s just finished. I mean, it’s still open, but it’s just finished, an 80 day fundraising campaign. We took in 50,000, but we also met a big investor who came in with 210,000 and said, pay me back that over ten years, I just want you to build that. There you go, there you go. Now I was in the head doing fun pitches and pitch decks and all kinds of in that world of appealing to the people in my life with money. Which I got very little of from any of them. And it was the ones who had nothing, who had like, I’ve got ten grand in the bank there, I could give you eight of it. I’m like, Jesus, what world am I living in that I can’t get it off somebody who has 50 million, but I can get it off somebody who has 20.

Diarmuid: Like you just you just wouldn’t believe what you’re stepping into, you know? But it all came and it has come and it’s now a potential. But the potential is also to slip into ‘now I’m doing this, I’m building this’. And how we do it is we organise based on the ancient principle of a gathering of the community to get work done. And so on Saturday, we ran a permaculture gathering where 25 people showed up, 7 or 8 children there amongst us, they’re playing, they’re listening, they’re seeing their parents interact, they’re seeing them work. They’re seeing the measure of the site. They’re seeing them use the permaculture principles to get the slope on the site. Measure where the water is coming from, measure how much water is coming in. All of these things like very practical. And everybody’s learning this skill collectively. Now, when I put out the call for the Stonewall building course, people are going to pay me to come in.

Manda: To build your stone walls.

Diarmuid: We’re going to build a sauna and we’re going to do the same thing. And on some of them it’ll be work parties, and some of them it’ll be paid retreats. And some of it will be central funding from the government who are investing in heritage skills. Particularly language skills, particularly heritage skills. As long as I can keep them at bay enough that if I say I want to convert the barn, because I’m building this retreat centre, my question with them is very much a push and pull base where I’m like, do you now want control of health and safety, engineers reports, all of it for the whole site? Or are you just going to do the barn that way? Because if you’re just going through the barn that way, I will dance through your hoops, your unnecessary hoops. I’ll dance through all of them. That’s fine for that. But you’re not getting control of the whole place. Because if I start to tend to you, I’m going to be the very same as the hotel up the road. I’ll start with the best of intentions, and I’ll end with just another thing servicing the machine. And I don’t want any business or as little business as possible with that. So I think that’s how it’s done, you know.

Manda: Yes. And then one of my baseline questions at the moment is how do we set up a new system that helps to accrue power to those with wisdom, and wisdom to those with power? And power being the power to give to people. I think one of the real toxins of our culture is that everybody thinks they need the power to have. I need the power to buy or have or take, and I need the freedom to not let anybody else encroach on my space. And actually, what we discover is that what we really crave is the power to give and the power to connect, and the freedom to do those things. And our culture doesn’t set up those freedoms. But you are setting up the freedom. You’re setting up all of the gatherings and the rituals and the retreats in which people will give of themselves to build a stone wall or build a sauna, which I guess will function like a sweat lodge at some point. And your local, the people who already have the power, you’re offering them the wisdom of a different way of being. And if they have a little bit of openness somewhere to feel the difference. And then there’s a way to go, hey, guys, this could be thing you could replicate this elsewhere. Then we begin to make the shift towards it being okay not to have to play the game. Please keep your thing open until this goes live.

Diarmuid: That’s the vision that it will be copied. Not necessarily I don’t want the philosophy or our beliefs, because that’s not other people’s beliefs, but definitely the essence. I see many of these centres popping up around the country. I mean, when I left West Kerry, I kind of had this relationship with the presenter of the Irish language radio station, Helena Hay, who was just this beautiful woman of a place who only wanted to know the social story. And that was her way of telling the narrative of what was happening. But she just focussed on people. And on my first trip to her, because it was not a big deal, but they were certainly aware of my arrival because I was an inter-county hurler and I was known. And so she got me in one day, just as I had arrived. And I went over to interview with Helen and she was like, What are you doing here? And I was saying to her, well, on my way over I cycled and it was about a ten mile cycle and I looked off the coast of West Kerry before I left my house, and I could see there was a storm coming. And I reckoned that there was about 15 minutes and it might take me that 15 minutes to get the village just up the road.

Diarmuid: So I cycled up and I stood under this little hooded area, and next minute this massive shower came in and I was under the hood of the area, and I stayed for about 20 minutes. And then I picked up my bike when it finished and I cycled over to you. But I was cycling the whole way over to you on the back of the shower. I could cycle into it if I wanted to, or I could pull back from it, and I’ve never had that experience in my life before. This was my response to her. And she was like, oh, you will be fine down here. Because they know there’s that little bit of madness. You know, they’re welcoming of the bit of madness down there, they know that it’s needed. But on my last interview with her, I said to her, a little bit tongue in cheek, and I was a little bit embarrassed by it afterwards, to some degree, but I stole a line from Braveheart. She said where are you going? And I said, we will invade Ireland.

Diarmuid: I’m going to take what I’ve learned here, which is the richness of the language, the richness of our culture, the strength of our people, the habits and the customs and the relationships that we have with nature and I’m going to bring that to the East. Which is that lovely, just as your beautiful phrase there a moment ago; on the East Coast we have wealth, and on the West Coast we have this wisdom. And we have a dearth of both on each side and so it makes sense that we would converge and share the wealth and share the wisdom and unify ourselves on a shared story. I mean, I think that’s possible. And so that’s how I see it to a degree. I feel like we’re coming into Ireland with this jewel, and I feel like it’s going to be replicated around the country in time, because there is this re-emergence, wherever it’s coming from, there’s this re-emergence in the Irish spirit at the moment. It’s in our music, it’s in our heart, it’s in people in a way now that I’ve never seen before. And we are taking part in that. I’m very delighted and feel very honoured to be taking part in it.

Manda: It sounds genuinely magical. Tell me a little bit more. It makes me want to move. I lived in Ireland for about 18 months when I was a veterinary surgeon.

Diarmuid: And where were you living?

Manda: At the vet school. I was near Dublin because the vet school is in Dublin, Trinity College. Although in the end I ended up living about an hour out west and I think we were in Kerry, but I don’t remember. I had a relationship and moved out to be with her. But the students sometimes would hold entire sessions in Irish. So I’m the person in the room anaesthetising the horse so I have to speak in English because I don’t understand it, but all the rest is going on in Irish. It was just like being bathed in magic. It was so gorgeous. And tell me a little bit about the the roots in the web of life that feel real when you’re speaking it.

Diarmuid: I mean, in the context of love, it was very enlightening for somebody who had been very extractive in relationship with women in particular. I found when I began to court Siobhan through Irish, I would maybe send a text and then I wouldn’t get a response immediately and I’d get a little bit paranoid maybe. And I’d look at the phone and say, what did I say there? And then I’d read the message, and it could be about going into town to collect mushrooms from the shop. And I was like, whoa, look at that’s a poem. Like that’s a sonnet. Like she’s gonna, whoa, that’s fine. There’ll be no problem. Then I’d get a message back from her and I’d equally be blown away by this. Oh my God, the beauty, the language. It’s a real thing I think for Irish men in particular, we’re very, very stunted emotionally in communication. Now, I know that is a feature of probably men everywhere to a degree. Not in all places, certainly, but I know it is a feature of maybe just of what we are. But I find the stuntedness in the emotional around anything that comes to shame and love and the emotional world. We don’t have words for it in English. And when we speak in Irish it flows. It’s just second nature to the language itself that you would speak. And it’s like the words are there for the thing already, that they don’t seem to be there in English almost. And I wonder if we spoke our language, if men would actually be nearly as stunted in Ireland. I wonder how much the English language actually stunted us in that regard. And maybe something that they knew that that worked elsewhere as well.

Diarmuid: And when you listen the old people; we used to go to this, oh my God, a gathering of Irish speakers down on a Friday morning in the library in West Kerry. And they would just take the language apart, Latin, English, French, whatever. There was no like, oh, Irish is the best language or you can’t speak English here. It was like let’s jam with language and where’s the roots of that? And the richness of communication was incredible. But I’d listen to them and the banter between the older people, 60, 65, 70 years of age, and they would talk about sex in a very, like there would be innuendo and the women would be giving it back to the men. And it was all very joyful and jovial, and female anatomy, male anatomy, talking about all the parts of the body, relationships. Like it was all on the table. And when it’s all on the table, it seems like it’s easier to navigate what you need to find because it’s all there. Whereas when you have to go, oh, well, there’s the channel for that of what’s acceptable and there’s a channel for that on that subject. Then I begin to get tense and I’m like, oh, can I say that? Am I going to get thrown out of the tribe if I say that? You’re in this selectivity and that’s all up here (head). So what I found was I could just communicate from my heart.

Manda: Yes, it’s a heart.

Diarmuid: Oh, that’s it really, isn’t it? It was very much facilitated, a heart centred communication. And there wasn’t very many times where I would say, that’s just how it was, you know?

Manda: It’s beautiful. And I’m thinking, as you’re saying this, so just get the history of the place for people who are not familiar. So I live in a world where initiation culture is all of human history and existing indigenous cultures, and it breaks somewhere around ten, 12,000 years ago, where we stopped being forager hunters and managers of land and become people who enslave the web of life. I own this bit of land. I own these cattle, I own whatever, and I will make it behave the way I want it to behave. And I am going to spend every generation fighting the web. And in the mainland island of Britain, we know that farming as we know it, that kind of enslavement to the land came over, lasted 2 or 3 generations. And then people went, sod this for a game of soldiers and went off and went back to foraging hazelnuts as their primary source of winter protein. Because foraging is much easier. You just wander around and pick what’s there.

Diarmuid: If you know where it all is, yeah.

Manda: You’re not trying to control. I very similar to you have somebody here and we just this morning dug the grave up the hill. And the stones, I was pickaxing stones and I was thinking, Imagine if we ever actually had to earn a living growing on this hill. I think it’s been sheep for its entire existence, it’s too steep to do anything else, but even so, take off the turf and it’s basically a bed of stones with some soil between them. And it’s hard work, and it’s uncertain because you are constantly battling the web of life. But before that, we were in flow with the web. I always remember, gosh, Hugh Brody, he wrote The Other Side of Eden. One of his books, it may not have been that one, and he worked with an indigenous tribe in the northwest of the US, and they were foraging, hunting still, this is way back. And they said, we have to get up very early at 4:00 in the morning by your watch time, because we’re going to hunt the elk. So he sets his alarm and he wakes up and everybody else is completely asleep, and he’s feeling very smart, and he goes away and wakes them all up and they’re going, yeah, but the elk are not here.

Manda: He said, but you told me. And they said, but they’re not here. Okay. And about three weeks later, they wake him up at four in the morning and go the elk are here! Okay! And they start walking. And they walk for three days without a break. And in the end, they have to make a travois and pull him because he can’t walk for three days without a break. So this is for a given definition of here, which says the elk are three days away, but that’s close enough. And everybody knew except him. And this is who we were, this is who we could be. And it has always seemed to me that from what we understand of the tribal relations, pre-Roman; Rome brought the trauma culture to the islands of Britain. They did not ever bring it to Ireland because they just didn’t want to go west. Or they didn’t bring it in the terms of colonisation in the way that they colonised the mainland. And that way we have the legends and the stories and men and women being much more equal. And you divorced someone by basically going, hey, I divorce you. And I don’t think even marriage was the thing in tribal structure.

Manda: Why would you bother? Unless marriage is a thing that gives ownership of a woman to a man and guarantees, ideally by basically restricting a lot of behaviour, that the children he’s raising are his. And then he can give property to them and believe that they are his. Mostly wrong, now that we’ve got DNA we discovered about 30% of people are not the children of who they thought they were. But, you know, that’s the theory. And there were eras in history where it was much more tightly policed. And Ireland was free of so much of that until the English really decided they were going to hammer Ireland. And so I’m wondering if the wildness of the language is much more of an actual genuine initiation culture language. So please riff on that. But I have a final question, which is Robin Wall Kimmerer tells us of the native languages in North America that they’re mostly verbs, whereas English is mostly nouns. And I’m wondering, is Irish mostly a verb? Is a lake a thing that you do? Or a loch a thing that you do? Is a horse a thing that you do rather than a thing that you sit on? Is that a thing?

Diarmuid: There are aspects of that. I would say because of our island nature, the lexicon of different aspects of life have been invaded at times. So for example the language of seafaring.

Manda: The Vikings or the Northmen came.

Diarmuid: So it has changed over time. One of the one of the key areas, I would say it doesn’t afford the same aliveness of maybe a Chinese person might afford. I mean, John Moriarty spoke about that as well. He wasn’t happy with the word landscape, because the landscape you’ve got land, which is an economic entity of some kind, and then scape with the vision of your eye. And he said, that’s not enough. So he coined a phrase meaning wonder manifesting itself over and over again. So allowing for the aliveness of things. So we had that in what we call silver branch perception. So it wasn’t necessarily in the language, it was in the way of seeing, possibly without language or before language or after language or some other place where it’s not necessarily tied to language. But in Silver branch perception we saw the aliveness of everything and we respected the aliveness of everything. And we weren’t looking at things with a use and benefit mindset. It was for its own integral, the sound of its own Orphic note, its own, you know, majesty.

Diarmuid: And so the differences maybe in the language that I would notice, because that’s also, you know, of a time past and now we are talking about an orientation in the present. And the cardinal directions. I know this is a feature of many of the indigenous languages. If I’m going to leave this room now, I will go south to the door even though it’s just there. If I’m going south to Africa, I’m still going south. But we were always orientated, we always knew what direction we were faced and that’s within the language. The place names are phenomenally interesting here, in the sense that they told so much about a place. It might be very simple, like Onya’s well. But it also may be relational to the name of the tree and that might be because of the type of soil in that area. So the hill or the church of the oak. And there would be information encoded in that, not just there’s an oak tree, but there’s the soil and the land that facilitates an oak tree.

Diarmuid: So it’s informational in that way. But I think the separation might be the fact that in our philosophy, where philosophy meets spirituality in a time where we were actually really connected. I mean, we might term these things magic now and scoff at them, but it’s only because we’ve lost the faculties with which to… Manipulate is completely the wrong word, but like to engage with, to engage with the environment in that there was a response. And that we had possibly forms of telepathy, of clairvoyance that again seem unobtainable to a limited mind now, but I think when you were in the mind of all things, in those times, it seems to be that’s what the reports come through history to say. That, no, there was a time where we could actually. Moriarty tells that beautiful First Nation story of the buffalo robe, and when the shaman put on the buffalo, he was buffalo. You know, he no longer was the shaman, he became buffalo. You could become at one with things in a different way. So yeah I think that’s that.

Manda: Yes. Thank you. You’ve opened up many more doorways but I’m aware of the time and we probably should stop. I have one last question though, based on what you were just saying. It feels to me that what you’re doing is essentially what we now call shamanic, but it’s more reconnecting with the living web of life. And that there’s a sense of the web is the whole planet, but there’s also a place based sense. When I go home to Scotland, I live in England now, but I go home to Scotland and the land feels different. The spirit of the land feels different. And it’s basically an island with a line across, but it’s had a different sense of people on it. It’s had a different sense of who we are. And when I was in Ireland, absolutely, the land felt really alive to me. And it had that wildness and it had that sense of self that I don’t always meet when I go somewhere. And I wonder on the edges of your being, in the places that we would now call magic, do you have a sense of the spirit of Ireland?

Diarmuid: I do, but I’m a little bit like, maybe with my role and the retreats and the retreat sometimes in myself to the boatman role, in not acknowledging that I actually also can be on that island and can guide very directly. I have it reflected back to me, and out of context, if somebody has listened to this full conversation, I think I might get away with it. As a fragmented clip probably not. But what’s fed back to me from the world around me, from the people close to me, and from the response that I see, this visceral response that I see in people to me. I feel like I am embodying something of a sense of what Ireland is. Some aspect of Ireland. Now, even saying that sentence out loud is a terrifying idea. Or it’s like, what are you talking about? But when I was young, I was red haired with freckles, and MTV just came into Ireland and there was like six packs and bouncy blonde hair and all of these things came in and I wasn’t it? And so I looked around and I thought, okay, I’ll try to be like all of them, because they all seem to be this American dream, European British culture dream. I don’t know what any of those things are, but it seems like that’s what people want from me. So I’m going to try and embody that.

Diarmuid: And then at 28, I had my breakdown and breakthrough, and I realised much has happened with the journey of the language. I’m not a native speaker. It only came to me when I was really in my late 20s, when I realised that life wasn’t this thing that you took in from the outside, that it was something that you let out from the inside, which has mirrored both in the game, in the language, in my relationships. Everything that I draw on from myself has ten times better results than anything that I try and take in and enact. So maybe again, it’s that maybe we knew, always, as other places knew. But that doesn’t matter. All that matters is that we embody our place. I mean, that’s been the great failing of the globalisation experiment. The idea was that we fell into this idea that we should have a monocultural approach, whereas actually the call for globalisation is for you to live your culture fully, so you have that to offer to the global community for all its richness and uniqueness. And so I feel at the moment maybe that I try to avoid at all costs, you know, the hurling and the wrestling and these things are beautiful, but they can also in that world of sales and social media it becomes a thing, and people are coming for that thing. And I’m like, no, I don’t want to do it now because you want this thing, and that means it’s not going to come from us. It’s going to be just this expectancy and it’s going to be inauthentic. And so I want to run a mile from that stuff. So I think there’s a freedom of expression that’s born out of a depth of awareness and knowledge and respect for the world around us that is essential to the Irish spirit and the Irish psyche. And I have discovered through partly many mistakes, partly not seeking to control or define or to align or to give my ego any opportunity to, you know, get Ahold of things too tightly, I seek to embody those things just as I am, without care for what the results of that are. And the more I do it, the more people seem to respond and say, whoa, what is that? And I don’t want to answer the question because I don’t want to know what it is. I just want to be it. And for that to be enough. And I hope it is Manda, you know.

Manda: I’m sure it is.

Diarmuid: Because there’s many people will say like, yeah, you can’t be that idealistic. You can’t do it that way man, you have to play the game. And I have other people in my life who are saying, like John Moriarty said to me when I was down in West Kerry. I mean, he said it through his writings, he wasn’t alive at the time. And I would encourage anybody who’s listening to follow some of the work, at least of John Moriarty. There’s a lovely tie in from where we opened. There’s an interview with Tommy Tiernan on YouTube. It’s about 12 minutes. I’ll send you the link. And it’s just an insight into the man, and you’ll know whether you want to continue. There’s many, many talks, many, many hours on YouTube. And this man fundamentally kept challenging what I was certain of what I was, until I’d read the sentence. And I’m like, right, I need to take a week now, because I’m not the thing I thought I was. I have to put a few pillars in a few different places because now it’s, you know, that’s the scale he’s been working at.

Diarmuid: And so, yeah, I’m following that feeling still from him, which is okay, you’ve gone now and people are saying like maybe you need to come back in and maybe that’s too much. We’ve a documentary coming out on the 12th of July, and it’s a very bare bones look at who we are and what we do. Called Immran and it’s at the Galway Film Fly. I don’t know what happens to it then, but it’s at this film festival in Ireland. And it’s kind of like, yeah, there’s people are going to reject it and they’re going to say all kinds of things, as they do. Sometimes they tell me I need help or that I’m this or I’m that, and I’m still listening to Moriarty, who’s still saying, Go on. Go on, further man. Go out into it, further. Go out into it and feel it all. Feel it all, you know. And I love that. Like I just think yeah. Yeah!

Manda: Yes! That. I think let’s end on that, because that’s so beautiful. Feel it all. Just Feel it all. Please stop playing the game. The game’s gonna kill us all. We don’t need it. If you could just get feeling it’d be fantastic.

Diarmuid: “Let me feel it all. Let me feel it now. Be it good or evil. Let it all come out”. That’s a Mick Flannery song, written by another man, but Mick Flannery sang this song ‘I’ve got a darkness’. And that’s one of the lines in it. And to the untrained ear and the closed mind, they’ll say, oh, that’s so heavy ‘I’ve got a darkness’. And his voice is so heavy, but it has to be heavy because of the weight. It’s a little ditty about intergenerational trauma, as the singer says. But that song goes through that, the darkness, and finds in the end that that’s the answer. Let me feel it all. Let me feel it now. Be it good or evil, let it all come out. And it gives hope to the boy in me who wasn’t sure. And it gives hope to the man who still isn’t sure as well, but is kind of… Yeah.

Manda: Yeah. You’re a wonder. Diarmuid thank you so much for coming on to the Accidental Gods podcast. This has been such a joy. I hope for everybody listening as much as for me. And I hope for you too. Thank you.

Diarmuid: Lovely Manda.

Manda: And there we go. That’s it for another week. Enormous thanks to Diarmuid, for the magic of his voice, and for all of the authenticity that he brings to what it is to be human and to be real in this world at this time. And particularly for all of the work he’s doing, helping people to detoxify from the horrors of what predatory capitalism is running away to. This feels so important. And just finding the language for it. Finding that English might not be the language if it’s not the native language of the country that you’re in, feels really important and beautiful. I could listen to Diarmuid talking Irish for the rest of my life and be really happy, even if I didn’t begin to understand what he was saying though. This does make me want to start learning. Anyway, that apart, we put a link in the show notes to Diarmuid’s fundraiser, which is a wild and magical place in its own right. I am looking down the list of things that you could still connect with while supporting everything that he’s trying to do. There’s a sauna with a wild food, foraged meal for two afterwards, or a two night apartment stay at the Black Sheep in Killarney. Or, I’m bypassing the learning Irish because that’s already sold out, there’s some beautiful art, there’s a mother in health child program, there’s a bilingual family gathering, and there’s birthrights in Gaelic. It’s really lovely. Totally recommend that you go there. You don’t have to be in Ireland. You could just contribute to what Diarmuid’s doing because it’s beautiful and lovely and utterly worthwhile.