#207 Bringing Indigenous food back to the people: a conversation with Josiah Meldrum of Hodmedod’s

We know we need to eat real food, but how do we make this happen? Hodmedod’s is leading the way in linking farmers to people to make the best of the land.

This episode was recorded at the Marches Real Food and Farming Conference held at Linley Estate in Shropshire in September.

I was honoured to be invite to speak and the recording you’re about to hear came from a conversation with Josiah Meldrum, co-founder of Hodmedod’s, which, as you’ll hear, exists to find markets for indigenous pulses, grains and other foods that were once staples of the British diet and had fallen out of favour with the rise of industrial farming .

What Josiah and his co-founders have done is to help create markets for the things that small scale regenerative farmers can grow and want to grow – and in doing so, they’re providing good, nutrient dense food to a growing population of people who understand what the return to a small farm future is about.

This sounds obvious – but in our hyper-industrialised world, where industrial farming meets the industrial food industry (ultra-processed foods, we’re looking at you), with their overt and covert advertising – it’s radical. Truly, spectacularly radicle.

This is localism in action. It’s the deliberate enactment of the values and principles that need to expand far, far beyond the shores of Britain if we’re to create the future we’d be proud to leave behind.

So, in the understanding that this was actually recorded in a barn, please enjoy the conversation – and if you’re interested in getting in touch locally to help with next year’s event, please contact the Shropshire Good Food Partnership. Similarly, if people in other areas interested in sharing on bioregional food and farming futures work then the organiser, Jenny Roquett, is keen to setup a learning space on this.

Coming up – Accidental Gods Online Gathering

Dreaming Your Year Awake – Sunday 7th January 2024

In Conversation

Manda: Hey people, welcome to Accidental Gods. To the podcast where we believe that another world is still possible and that if we all work together, there is time to create the future that we would be proud to leave to the generations that come after us. I’m Manda Scott, your host in this journey into possibility. And this is our first live podcast, recorded at The Marches Real Food and Farming Conference that took place on the Linley Estate in Shropshire back in September. For those of you who don’t live within easy reach, the Marches are the borderlands between England and Wales, specifically between Shropshire and Herefordshire on the English side, and Powys on the Welsh side. And they’re called the Marches because for several hundred years, when England was endeavouring to colonise Wales, the border lords would march up and down and basically bullied the Welsh into submission. And they succeeded. Wales did sadly become a client state of England. There is always the hope that it will throw off the shackles and regain its independence, like Scotland. But that’s if geographical states continue to be a thing, and I am beginning to realise that that might not be the case. We will talk about that in a podcast coming up soon. But anyway, medieval history apart, the Oxford Real Farming Conference is held in January each year and has grown to a week long event attended by thousands of people in person and online.

At the end of the conference this year, Colin Tudge, one of the founders, said something to the effect of now go home and make this happen in your own areas. And a genuinely remarkable woman by the name of Jenny Roquette, took this to heart and in less than six months set up a two day conference with three streams of speakers going all day, every day, in our part of the world. I was honoured to be invited to speak, and the recording you’re about to hear came from a conversation with Josiah Meldrum, co founder of Hodmedods, which, as you’ll hear, exists to find markets for indigenous pulses and grains and other foods that were once staples of the British diet and fell out of favour with the rise of industrial farming. What Josiah and his co-founders have done is help to create markets for the things that small scale, regenerative farmers can and want to grow. And in doing so, they’re providing good nutrient dense food to a growing population of people who understand what the return to a small farm future is all about. This was the second event in a row that Josiah had done, and we do refer occasionally to the first. So I’m going to tell you a little bit about it.

It was a four person panel with Josiah, a farmer who grows old style indigenous wheat species in Shropshire, a miller who mills the grains in a refurbished water mill, and a soil and food scientist who was assessing what was working and what wasn’t of what they were growing and milling, and the resulting baking that was taking place. I might see if we can get recording of that too, because it was fascinating. But my real takeaway, after listening to the stories of a farmer who was able to come back to the land and to start working with it to increase biodiversity and the diversity of the grains that he grew. And then the amazing woman who put the time and effort into working out how to mill things that hadn’t been genetically engineered basically to turn into powder as soon as they were hit by steel roller mills. And then learned that there’s more iron in the old biodiverse types of grain. And if you bake it as a sourdough loaf, that iron is 75% more bioavailable than even the iron in a long leavened loaf, and definitely much, much more iron than industrially farmed wheat put through industrial steel roller mills. And what we learned on top of that, was that the industrial food scientists learned this, and they don’t say, okay, everybody should be eating sourdough wholemeal loaves made from multiple diverse old species of wheat. What they try and do instead is engineer industrial wheat species with iron in the endosperm. And iron kills the endosperm. So this is a really hard thing to do. And I would suggest stupid.

However, we learned all of this. It was all very interesting. And then someone put up their hand in the question time, an organic farmer from around here, and said he really wanted to start growing these types of grains. And I watched the entire panel go rigid and they said, essentially, you can’t do that, you’ll flood the market. At the moment we have all the grain that this particular mill can handle, which is 20 tonnes a year instead of 20 tonnes a day or whatever the big steel industrial roller mills do. Probably not 20 tonnes a day, but you get the gist. So they have small amounts of flour going through on a field by field basis. And then they have bakers who are prepared to work with non-standard flour that responds differently, that has different constituent components in different ratios than industrial, highly standardised wheat. And from that they bake sourdough or long leavened loaves, which at the moment have quite a small market. So if I understood correctly and it makes a nice linear argument from where I’m sitting, we have agency in this.

It’s the people who are buying the output who are the rate limiting step. And that applies to everything that Hodmedods is doing. They are endeavouring to go to the farmers and ask them what they actually want to grow, and then finding markets, making markets in some cases, so that the farmers can gain an income from growing what’s good for them and what’s good for the land. And if you’ve listened to podcast 202 with Anne and David, who wrote What Your Food Ate, you will know by now that eating the product of good regenerative farming, where regenerative means no chemical inputs and minimal or no till, building soil biodiversity, that is the kind of food that we want to be eating. It’s the kind of food that bolsters our gut biome in ways that we want. It’s the kind of food that has the right ratios of omega three to omega six essential fatty acids. It has the iron that we need. It has all the micronutrients that we need.

So at the end of this podcast, I have some ideas that I will lay out of what we can all do to really make a difference to this. But in the meantime, in the understanding that this was actually recorded in a barn and Alan has done his best with the sound, but hey, it’s not quite the same as studio sound. People of the podcast, please do welcome Josiah Meldrum of Hodmedods at the March’s Real Food and Farming Conference.

Thank you everybody. Welcome to those who were here earlier. We’re going to endeavour not to cover exactly the same ground with Josiah as we just did, but we will inevitably cover a little of the same. And yesterday we started with a quote from Ilya Prigogine and I just wanted to start today with something that I think really fits well with what Josiah is doing, which will be known to all of you, but it’s just bringing in the focus. Of Buckminster Fuller, who says the way to change a system is not to try and break the old system, it’s to create a new system that makes the old system obsolete. And I think we’re all here with an aim, one way or another, of systemic change. And Josiah definitely is part of doing that; creating the new system within the old system, that will in the end make the old system obsolete. So Josiah, co-founder of Hodmedods over in East Anglia, can you tell us to begin with, where the name Hodmedods came from and how the whole concept arose?

Josiah: Yeah, happily. I love that quote, by the way. It’s a quote we used, we published a little journal called Sheaf, and I used it in the last edition of sheaf as an introduction. And one of the things I couldn’t find, and I’d love to know if you’ve got it, is where that is from. It’s unattributed.

Manda: Yes, that’s very true. It’s 1971, but I don’t know. I’ll look, I’ll find it. You looked probably too, but yeah. Anyway, it’s a good quote. Even if he never said it, it’s still a good quote.

Josiah: The best quote. So I’m Josiah and I’m co founder of a business called Hodmedod which you may have heard of. And we work with UK farmers to get more diversity onto farms and more diversity onto plates. We are that demonised thing, we are a middleman and we are all men I’m afraid. And too often that is the case in the food system. But actually that is an incredibly important role, because we are facilitators and enablers of system change. We connect farmers to food citizens, reframe consumers as food citizens, and create routes to market that enable really positive farming change, allowing farmers to do all of the pro-environmental work broadly that they want to do, but also to grow nutritious food that reaches people. And our story started almost 20 years ago. So if you want to know how to get here, it takes 20 years. And that’s that’s a problem because we really don’t have 20 years anymore. We started, Nick William and I, who went on to found Hodmedod, we started working for a number of different local food organisations and ultimately for an organisation called East Anglia Food Link, based in Norfolk, but working with with the counties of Norfolk, Suffolk, Essex, Hertfordshire and Cambridgeshire. And looking at what food system change might look like. And we did things like we took procurement officers, so that’s people at the council who bought food for schools; we took them to Italy to show them that European law in the early 2000s was not a reason not to buy local food, you just need to want to do it.

We encouraged farmers to convert to organic in that period, in Norfolk and Suffolk. We established some of the first farmers markets in East Anglia at that time, as part of this idea about what a relocalization of the food system might look like. We worked with local authorities, we worked with hospitals around changing where they bought their food from. And most importantly, perhaps, we worked with communities and people who wanted to have a connection with where their food had come from. This idea that food is this catalyst for change, because it is, and it is a cliche, but it is the thing that we all do three times a day, and it’s a way that brings us together, communicate with each other, and we can make change happen through those interactions.

And we got really, really frustrated with what was happening at a local and national government level. There was only so far we could go with Defra or a local authority. You know, a local authority might say, well, we’ve got 10% local food in school dinners, no one’s really asking us to do any more than that. And it’s easy not to do any more than that. And we got really frustrated and we started working much, much more directly with community groups. And one in particular: Transition Norwich, which was part of the national and global Transition movement, which is all about how we are going to cope with a resource constrained planet that’s experiencing climate change and biodiversity loss, and what we need to do in order to change the systems around that.

And they asked us, could Norwich feed itself hypothetically in a low input, low impact way? And we did what NGOs have a tendency to do, which is we produced a report for them. Because that’s how you change the world, isn’t it? You write a report and it’s all sorted and it goes on a shelf and no one ever reads it again. Except Transition Norwich didn’t do that. They came back to us and said, that’s a great report, let’s make it happen! And we had developed three scenarios in the work that we’d done. Which was a kind of business as usual model; so our diet doesn’t change and land use doesn’t change, can Norwich feed itself? No it can’t. We had a vegan model, interestingly; what if we completely eliminate livestock? This is in 2008. So these were not such current ideas at the time. That doesn’t work either. What worked was a system where there is a small amount of livestock eaten, but that are in the system and their nutrient cycling. And we’re growing a lot more pulses and leguminous crops, both to fix nitrogen and for human consumption. And we needed and this is critical and it’s missing everywhere; we needed a renaissance in horticulture. Horticulture is massively missing within our food system. And Norwich itself would have been surrounded by a ring of market gardens that would have supplied homes, restaurants, markets with with fresh produce.

And now most of that is grown in areas where there’s a lot of specialism, like Lincolnshire and around Hampshire, but a lot of it is coming in from Spain and from the Mediterranean, and we don’t have that capacity anymore. So we did this report, we gave it to Transition Norwich, they said, let’s do it. We set up a community supported agriculture scheme on the edge of the city in 2009-10 ten; nine acres of land to feed 150 families, two part-time horticulturalists paid to work on that land. And it really demonstrated how really difficult it is to do that. It’s still going, it’s called Norwich Farmshare, and it’s a brilliant way of engaging people very directly with how food is produced, because it’s dependent on volunteer effort. If nothing else, it gives people a sense, when they go into the greengrocers or into the supermarket, which is more likely, and they see a 50p lettuce, they think bloody hell, how do you grow a lettuce for 50p and get it into a supermarket in a bag? That is the realisation. We worked on bread. So Norwich is in the middle of obviously a big area of arable production. So that’s combinable crops, cereals, oilseeds, sugar beet in some senses, barley, beans. But all the grain around the edge of the city would be going off to big plant bakeries to make Chorleywood process industrial loaves that then return to the city in plastic bags of unknown origin.

Josiah: And I think what we wanted to do is demonstrate that if you put a mill in the middle of the city, in the hands of a really good baker, they can make a loaf with anything. And I think for us, the big sort of Damascene moment about that reconnection and about food and about grain, was going to visit the farmer who was going to supply us with some of his commodity cereal. I don’t know what variety of wheat he’d grown, it was just what he had in his grain store. We took a little tabletop mill and a bread making machine, and we milled some grain that we’d taken from his grain store in the kitchen. We put it in the bread maker, and then we went for a farm walk, and we chatted and we came back and the loaf was smelling amazing. We took it out of the bread maker. We cut it, we ate it. And this hard nosed, you know, kind of I’m a rational economic actor East Anglian farmer, just welled up and started crying. And that was a really moving moment because he said to us at that point that it had never occurred to him. And I’m sure there are farmers in the room who may share this experience. It had never occurred to him that what was in that grain store was food, that it was something that he could eat.And in 40 years of growing those cereals, he’d never thought to make a loaf of bread out of his own grain. And I suspect, particularly in East Anglia, there will be a lot of farmers who are in that position. And that’s when we realised there was this incredibly important role for reconnecting farmers with the food that they were growing, as well as those food citizens or consumers, with the food that they were growing. I’m going on a lot, aren’t I? And the final part of that Norwich project, because the bread and the vegetables, they’re quite charismatic. People can hang on to those. You can can really smell them and sense them and touch them and hear them squeaking. If they’re a cabbage. But there’s a part of the rotation which is this leguminous bit, these crops and plants that do that extraordinary thing of taking atmospheric nitrogen, working symbiotically with soil organisms, bacteria, rhizobia that will then turn that nitrogen into nitrates that the plant can use to grow, and that, more importantly, leave some of that nitrogen in the field, which can then support a following crop, or it can support a crop that’s growing simultaneously with that legume. And that also if you grow a variety that you can harvest, like a bean or a pea, that puts that nitrogen in the form of protein into a seed that we can eat, and that can become a really important part of our diet.

And we left that bit to last because we thought it meant that we’d have to get everyone in Norwich to eat beans. And we didn’t want to do that and we thought they wouldn’t want to do that either. And we began at the end, talking to farmers about what they were already growing on their farms. And we began to have more and more conversations with farmers who were growing field beans or fava beans. Vicia faba, which is a small broad bean seed, which in our minds had always been animal feed. And we were increasingly coming across farmers who said, well, if I get the right quality and I’ve harvested at the right time, then I’ll get a premium because I can sell into North Africa, into the human consumption market. And we thought, that’s interesting. Human consumption market for this animal food? And it became clear that historically, these beans, these small broad beans that look black and wrinkled at the end of the year. You might have seen them in the fields, they look like a disaster has happened. Someone sent us a picture on Twitter and said, what is this blackened hellscape? And we said, no, that’s our crop, don’t Knock it. And historically they came here in the Iron Age with the first farmers. They were a critically important store of protein, but also more broadly macro micronutrients through the winter, when early farmers weren’t really in a position to keep livestock through the winter because they were expensive to feed.

Josiah: And we didn’t really have sort of dairy and cheese processes that allowed us to keep significant quantities of animal protein over winter, so that you fall back on beans. So we have all these midwinter festivals, eating the last of all those lovely things, and then you’re on the beans. And that is a problem. So when we went through the Industrial revolution, which coincided with what’s often called an agricultural revolution, although it wasn’t really revolutionary in that sense, it was a much slower process. We got rich and beans were stigmatised. If you had to eat beans, you were poor. And so they just fell out of the written record. They were probably still quite widely eaten by people that didn’t have much money and needed those crops. But as a high status food, they went from appearing in the first recipe book written in the English language, which was the royal household, to almost nonexistent in the written record by the 18th century, because they’d been stigmatised as a food of poverty. But the rest of the world carried on eating them. And so it became our interest to see whether we could persuade people in Norwich to consume them. And we bought a ton of split beans that were due to go to Sudan. And I apologise to the Sudanese for taking away something that they probably were looking forward to, and we put them into little packets, and we got a friend of ours to paint a postcard which explained what the bean was, and asked them what they thought of it. And it was postage paid. And we tucked them into the bags and 2000 packets went out across Norwich in various ways through shops, box schemes, events and we thought, well, I wonder if people will even eat them.

And then we started to get a few of these little postcards back and they were very positive. And obviously the people that ate them quickly would be very positive. And then they began to really stream back, and we were getting recipe suggestions and people saying, why have I never thought of these as food before? I’ve seen them growing all the time. Where can I buy them? And you can’t buy them anywhere. And we realised that we were really on to something and that things had changed. The stigma wasn’t there anymore. It was a cultural memory, but it was not in our consciousness. And that food in the UK has done an amazing thing over the last 20 years. We’re so much more open to a diversity of foods and cuisines, and that North African Middle Eastern foods are really, really popular, and that there’s this vital ingredient that you can’t actually get in the UK. So we began simply by selling fava beans that would have been exported. And we added to that peas as well.

And peas in the UK are often grown here, but they’re also often imported from Canada or from other parts of the world, and you never really know quite where they originate; many countries or whatever it happens to be. And for two years that was all we did, and it was very small, from 2012 to 2014, when the volumes that we were selling got to the point where we could begin to directly engage with farmers and ask them to grow specific crops for us in particular ways. So where there had been no organic beans for human consumption, we could ask farmers to do that. Where there had been no organic peas for human consumption, we could do that. And Mark, sitting in the audience, is our first organic pea grower and still our organic pea grower, which is fantastic. And a hodmedod is a dialect word, because like these forgotten foods, we’re losing a lot of our cultural identity and a lot of the local words are disappearing. And a hodmedod is, depending on whether you’re in Norfolk or Suffolk, and unfortunately, I’m not in either at the moment, so the arguments won’t open up at the end; it’s either a hedgehog or a snail. Interestingly, if you’re in Berkshire, it’s a scarecrow. I don’t know what they’re thinking. Essentially it’s a small curled up thing. It’s also an ammonite. It’s used for a girl with hair in overnight curlers. They’re called hodmedods.

Manda: Ok! Anything curly.

Josiah: I think so, yeah.

Manda: Hedgehogs, curly. Okay, guys. So when we form the Marches version of Hodmedods, we have to have a name that has multiple different uses and sounds old. I leave it to you. It could be Welsh, I guess. All righty. So there is still a huge amount to unpick. I don’t want to unpick too much of the modelling, but I’m really interested in you had nine acres and you thought you were going to feed 150 families right at the beginning, and that is still going. There are a lot more than 150 families in Norwich, I have been there. In your original model of yes, it should technically be possible to feed all of Norwich. What was the land area and how much of a radius were you allowing?

Josiah: Yeah, so obviously East Anglia is a food producing part of the UK and it has an obligation and a responsibility to feed more people than the people that live in East Anglia. And I think that’s pretty obvious really. And so the modelling we did for Norwich needed not to compromise that broader responsibility. And the business as usual model didn’t allow us to do that effectively and it used a lot of land. And the vegan model also did, because if we weren’t going to use inputs, we needed a big fertility building period. We weren’t using animals to accelerate that nutrition, that nutrient cycling process, So we needed a lot more land to build fertility in the soil. The ultimate model, I think the radius was about six miles, but it was uneven. So we followed some of the valleys where we needed some of that space. I mean, we were mapping a territory. We did

Manda: But that’s that’s not a huge radius. I mean, it might take you to Kings Lynn and then the radius of Kings Lynn merges with the one for Norwich. But I’m thinking if we’re moving into a post-fossil future where localised food becomes essential, because simply transporting it becomes hard, and we are not going to endeavour to get back to a peasant past, but we want to create a 21st century model. Can you see a future, this is leaping ahead a bit, but we’ll go for it; where a six mile radius around urban areas, even if we have to take the very big urban areas and and move people out and make smaller ones, is that a viable model that you could see in existence?

It’s an interesting question. I mean, what we did in Norwich was a thought experiment. And Norwich has a population of 160,000. So a fairly reasonable number of people. There’s always a question about the absolute desirability of relocalization in a total sense. And I I think there are things that, you know, I love chocolate and coffee. I don’t want to stop eating bananas. And, you know, we’ve traded since the Iron Age. We’ve brought wine and olive oil into the UK. So we’ve always had these relationships. And traders are really important facilitator and enabler of of other forms of communication. So we don’t want to go to some kind of totally insular place. And I think, you know, thinking of the UK as a unit, there are places that are really well suited to producing particular things. There is a comparative advantage in growing cereals in East Anglia and thinking about meat and dairy products in this part of the world. Or cereals that are better suited to a wetter climate, whether that’s oats or barley. So I think it’s thinking about what the complexity of that model might be. And I would suggest that something like horticulture could be radically re localised everywhere, because there’s always going to be a lot of things you can grow. But at the same time there are vegetables that are better grown at a field scale. So potatoes for example. You might want to focus on high value vegetables and allow the potatoes to happen at field scale. It’s really understanding what the appropriate scale for anything is. And that’s complicated.

Manda: It is really complicated. And we don’t necessarily have to dig into it now because it’s a bit of a rabbit hole. It seems to me while we have the fossil fuels to build the infrastructure, it would be a good idea to have that infrastructure in place for when we don’t have the fossil fuels to build the infrastructure. And understanding what things are good in East Anglia, what things would be good in the Marches. What things need to be actually grown within ten miles of your house. Getting that thinking done and getting it organised would be good. Is anybody aside from you guys doing this?

Josiah: Yeah. So I think there’s been quite a lot of work. The Sustainable Food Trust have recently published their Feeding Britain report, which essentially carries out the exercise that we carried out in Norwich in 2008, for a national level. There are organisations like growing communities in London who are urban market gardeners. And they’ve produced a model called the Foodshed, which is how proximate should particular things be grown? Salad leaves, you need them really fresh, you might grow them as close to the point of consumption as possible. Potatoes could be grown further away and might benefit from being grown at a larger scale. So it’s identifying and mapping those different things.

Manda: Okay. Exciting. All righty. Let’s head back to your history. And so you’ve got a farmer who’s now growing peas for human consumption. Are you offering to farmers who want to come into this, here’s a model; we can provide you with a market, these are the things we would like you to grow. Or does somebody come along and say, I want to grow peas, how many peas can you sell?

Josiah: It’s a bit of both, really. So Mark asked us how many peas we could buy and we didn’t really know, but we took a punt. And there is a degree of kind of figuring it out as we’ve gone along. So for us, we’re thinking about radical systems change and what that looks like in practice, both as people that eat food and people that grow food. And what really excited us about pulses as a crop, is that they’re a fantastic lever within system change. When you’re looking to effect change, you need to identify levers that are accessible and then that have a big knock on effect to the rest of the system. And we felt the amazing thing about pulses is that they are at the moment, and this is broadly still the case, it’s definitely still the case; they’re at the periphery of most farmers rotations. They’re the sort of thing that you have to grow, because you need a disease break, that you might need some fertility, but you don’t see them as a particularly valuable crop leaving the farm. And you don’t necessarily therefore put an awful lot of effort into producing them because you know, there’s a limited return on those. And we realised that if we could refocus on pulses and put them at the middle of the rotation, and value them properly, then we could start to think about what crops we could put around those pulses. Growing more of them for human consumption would shift diets, and would begin to affect change in what people were eating and nutritional intake and how they were consuming food. And that was our lever. And so we didn’t have a model, we didn’t go to Mark and say, this is the model. We just thought we’d sort of work it out, as an iterative process I think it would be fair to say.

Manda: Okay, so two avenues to go down. You’re interested in radical systems change and you’re looking at the levers of change. Radical systems change, as I understand it, explicitly says we don’t know where the emergent system is, because if you can see it from the existing system it’s not an emergent system. But you can take the existing system and push it to the edges. What are your principles and aims of the radical systems change? And what are the levers that you’ve identified aside from legumes?

Josiah: Yeah. So there’s what happens in the field as a lever for change. And and then there’s how we all engage with each other as a catalyst for change, rather than a straightforward lever. Because in an emerging system you need to allow space for emergence. And you can only have emergence if you have conversations and people engaging with each other. So one of the kind of conceptual sort of models that we use is that we want to abandon linear thinking in food systems. So that’s moving away from a supply chain where you’ve got a producer at one end and explicitly a consumer at the other end, and various gatekeepers who are managing value and information and knowledge and may or may not pass that backwards and forwards. But there’s a definite lack of transparency. To thinking more about relational networks of supply, where everyone can talk to each other, where there’s transparency about value and about exchange, and about who’s who. And no one prevents anyone else from talking to anyone else, because that’s the way you stifle innovation. And that means in practice that we put Mark’s name or whoever the farmer happens to be.

I’m picking on Mark because he happens to be right in front of me, on the packet. And that opens all sorts of doors for Mark and his farm, because people will approach him directly and ask him to do different things and other things. And that’s happened with all the farms that we work with. But it also means we’re very open to other businesses who might in a conventional sense, be our competition, but we see them as collaborators in a change process. Our competition is is Tesco it’s not the small mill down the road. And it means that we can introduce creative and imaginative thinkers, whether they’re in the research community or whether they are writers or journalists, to all of our farmer network and allow them to share that knowledge. Because we’re not the best conduit for that knowledge sharing, and it means that we can introduce farmers to each other and they can offer each other mutual support. Whether they’re organic or non organic or wherever they might be on a spectrum of change.

Manda: Brilliant. So I’m beginning to see an image. Because one of the things that I think, certainly when we’re talking to people in the outside world for whom systems change is not their daily thought, they are afraid that those of us who want systems change are trying to take everybody back to the Dark ages. And the Dark Ages weren’t fun, and therefore we don’t want to go there. And what I think I’m hearing is that we’re using modern 21st century technology to produce serotonin meshes of connectivity, which are then, I would assume and hope, in a way, going to counteract the dopamine addiction to the transient dopamine hits of the rest of our culture. And that we could not have done that in the Dark Ages because we didn’t have the connectivity that modern technology allows. Am I fantasising or is that a useful way forward?

Josiah: That would definitely be the way that we would see it. So one of the things we’re often asked by technologists is what technology can we build that will transform the food system? And lots of people have tried to do that and not really succeeded. And the answer is it all actually exists already. And things like Twitter and Instagram and social media, much as they might have downsides have been incredibly positive for connecting people and sharing knowledge. The number of not necessarily new entrant farmers, but next generation farmers, who’ve maybe had a different job, haven’t gone to agricultural college and returned to the farm, have learned so much about farming change through YouTube. I mean, it’s extraordinary. And you can connect to an international community of people that are thinking very differently and work out how you might apply those to your own context. And so I think that’s really exciting. And the same goes for the infrastructure that exists within the current system. So we think people are the most important part of the change process, fairly obviously. And it’s not about buying new mills or setting up new infrastructure. That exists. What we need to do is repurpose it. We need to identify where it is, we need to build relationships with those people, and then we need to repurpose their function. And that’s really exciting because it means that we have conversations with businesses that might in other conversations be demonised, but who are also interested in this change process and figuring out how that might work. And that is quite interesting.

Manda: Okay, I’d like to go down that route, but before we get there, in our other discussions, you and I have talked about farms. Possibly Mark’s Farm or other farms, where you’re beginning to develop circular economies on the farm. You’ve got the baker coming onto the farm etc. Can you talk a little bit about how that evolves?

Josiah: Yeah. So we don’t do that.

Manda: That just happens? An emergent property?

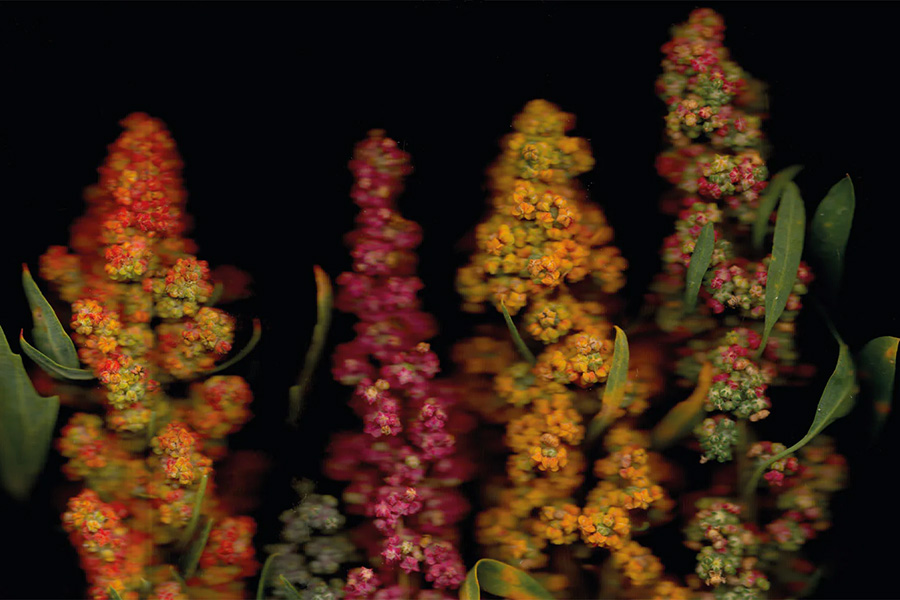

Josiah: That’s often a product of changing the way that you think about your farm, or a farmer thinking about the way they think about their farm. And part of that can be facilitated by us coming in and saying, let’s think differently about your food crops. And that will often open the door to people getting in touch, who maybe are bakers or millers and want to be on a farm and do that particular thing there. And that’s happened on quite a few of the farms that we’ve worked with. Our nearest farm that we work very directly with is Wakelyns Agroforestry, which is a very small scale holding in Fressingfield in Suffolk, which was the home of Ann and Martin Wolfe. Martin was a plant pathologist and then a plant breeder who developed the yield quality wheat population, which is in the middle here. And when Martin and Ann died 3 or 4 years ago, after long and happy lives I should stress, their family took on the farm. They weren’t plant scientists or researchers. They needed to find a new way for a very small farm to function. And I should say it’s a very interesting farm. It’s a it’s a pioneer of agroforestry systems. So for 25 years, the Wakelyns agroforestry has demonstrated essentially four systems of agroforestry: fruit, short rotation coppice, standard trees and a control area which is which is open fields. And what David and Amanda, who took on the farm from their parents, realised is that they needed to have more enterprises to hold value on the farm and to make the whole system work, and for it to continue to be a teaching and education space. So they have a mill and they have a baker, and they invite people to the farm to experience that system and to take away what bits of it might work for them. And that’s also been a really important catalyst.

Manda: And so, from starting with nine acres and 150 people, you took 20 years, but it seems to me as if the ramp has been quite steep recently. That it sounds like there was an early learning period, and now there’s the flourishing period. And I’ve heard you say elsewhere, you don’t want to grow. If anybody wants another Hodmedods, they need to make their own. And yet I buy Hodmedods products from Harvest Health Foods down the road, so you are selling quite widely. Is there room for other iterations of what you’re doing around the country, do you think?

Josiah: Yes. Good question. It would be lovely if there were. And I think this again comes back to this whole idea of appropriate scale. I mean, if you read Schumacher’s Small Is Beautiful, I feel like the book should have been called Appropriately Scaled is Beautiful. And when you read the book, that is actually what he’s saying. And I think if we’re talking about cereal systems and combinable crops, it is quite a large scale. That’s the scale at which they function most effectively and where they work in a farm context. And that means we need a lot of people to buy and eat those crops. And we would love all those people to be in the Waveney Valley, our bit of East Anglia, or in Norwich. But they’re not. And so to effect change, we need to find as many people as possible who want to eat the things that the farmers we work with are growing, and that does mean reaching out across the whole of the UK. But maybe as the change emerges, more and more people will want to do that, and there will be space for other iterations of that. And it’s happening in particular with grains, I think, although not perhaps so much with pulses.

Manda: As we were talking in the previous conversation.

Josiah: Absolutely.

Manda: Is that one assumes, because more people eat grains and they are prepared to experiment with sourdough bread, it became chic. Whereas eating lentils is still a niche.

Josiah: It’s a bit hairshirt, isn’t it? I think there is that image problem. We all eat bread and I think introducing crops that people are maybe unfamiliar with or don’t usually eat is a bigger challenge than just swapping a particular crop in their diet. And that’s the challenge with the the relocalization of those other crops which are critical to sustainable rotation. So we need to be eating them.

Manda: So as a writer, I’m thinking in the thrutopian writing that we’re trying to create, of writing the way through to the future. Part of that would be writing television series and television documentaries and other things, getting rid of the business as usual in the span of what we read and watch and listen to. And start inserting different ways of doing things. But we need to come back to you and to the farmers to find out what it was that you needed us to say. That’s a whole other conversation, I think.

Josiah: But that is why you’re so important, as writers and communicators and storytellers. We need to create these new narratives about what change looks like and to normalise, as it were, these crops. And we also need to get away from the fact that I’m on the stage. That’s a problem in all of this. That within storytelling currently, we’re very wedded to the hero’s journey. You know, we start in the darkness in obscurity and challenge, and then we go through, we meet a guide, we go through various stages, and we come out the other end where we’ve grown lentils, we’re heroes. That is not a good place to be if we want to create these networks where everyone has a role and there’s equality and distribution. I shouldn’t be up the front being the hero. We should be asking everyone to be part of this story. And within modern storytelling it is a real problem. So when we speak to journalists, for example, particularly in the more conventional media, they want that narrative arc. They don’t want a messy story that doesn’t really have an end.

Manda: Yeah, yeah. And they do want some person to be the hero. That’s a whole other conversation, because I think we’re hardwired for each of us to want to be the hero of our own story. And the way that story works is that we empathise with one or more characters in the story and can see them reflected in ourselves. And if we don’t have someone who feels slightly heroic, I don’t think we get the same serotonin and dopamine tweaks that we would otherwise get. But I think there are ways of creating heroism in a community that then you can reflect back to. As a narrative art, it’s hard. It is hard. I am trying to do it at the moment, and it’s incredibly hard, actually. And then the producers or the publishers come along and the editors, and they go, no, actually, we need you to bring a person out of that because otherwise no one’s going to read it. We might we might train the reading public. That’s a whole other conversation too. Because we’re heading towards the end, I believe. If there were room and if we wanted to create a Hodmedods in the Marches and we had a good name. What have you learned? What would you do differently? What would you do the same? If we had no constraints of money or time or people and enthusiasm, if we had people who understood systems change and levers of change at the heart of it. And we were aiming for a similar model of systems change as you have. What would we do?

b I think you’d just do it, because you’ve got all the bits in place they’re.

Manda: No that was meant to fill ten minutes!

Josiah: The challenge is the people and the consistency and the doing of it. And it’s finding the right people that are willing to commit to what turns out to be an awful lot of work. Right. All businesses are purpose driven these days and I’m slightly sceptical about that whole thing, but we have a real drive. You know, this is our job, but it’s also our vocation. I’m here on a Saturday, you know, and it’s the other side of the country, because I think it’s really important to to engage with people and to explain what we’re doing. So it’s really about a realisation of how hard it is and how you need other people. You can’t do it on your own. You need to be open to conversations. You can’t come at it with that conventional, closed, kind of competitive edge vision for what a business should be. It needs to be a collaborative model, and you need to be really open about making mistakes and taking advice, and you need to talk to people who you may not feel comfortable talking to. Because they may be part of what you see as the problem, but also they hold the keys to the change that you need to see happening. So you’ll need grain cleaners, you’ll need seed businesses, you’ll need all of these people and you’ll need to have conversations with them. And it’s very tempting to think we’ll do this on a small scale, but the scale of the change is huge. Let us not lose sight of the climate and biodiversity crisis, and that’s just two of the issues we face, that we’re up against, and the rapidity with which change needs to happen. There can be no closed doors to conversations. We talk to everyone from from small scale market gardeners all the way through to Unilever if they want to have a conversation with us, because it’s so critical that we’re having this conversation with everyone.

Manda: Does Unilever get it?

Josiah: They think they do.

Manda: Okay, that was an open question. I mean, I struggle to imagine that they do, but I imagine there are people within Unilever who get it.

Josiah: Exactly. And this is where people come in. So obviously a corporation is an embodied thing. It has its own identity and it exists. But it’s full of people that make it work. Turning it and changing it can be really, really difficult because these businesses are structured around shareholder value, and that’s massively problematic. And we need to think about how our businesses are modelled in order to affect change. But there are people that have exactly the same concerns as we all have, and framing what the change looks like so that it means something to those people is really, really important. And if we talk to enough of them and enough people who are concerned and have families and care about the planet, we can make that change happen.

Manda: And you’re modelling it for them. You’re modelling a way that even within the existing system, you are still flourishing, which has to help. I learned recently of the future Guardian model at Riversimple. Have you heard of that?

Josiah: Yes.

Manda: So for those who haven’t, instead of having a shareholder model, they have six separate sets and I’m not going to remember them all. But the workers, the local community, the environment, the customers, the supply chain and the shareholders. And I am, in fictional terms, adding on a seventh, which is future generations. And each of these has an equal say in the running of the company. And so everything that they’re doing, they make hydrogen cell cars, but everything that they do, their actions back up their own supply chain. Which means that the people who are supplying them have changed the way they design the catalytic batteries that fuel the cars, so that they can instead of selling them a battery, which will have a finite shelf life, it is still owned by the company that makes it, and they lease it to Riversimple. But then it’s in their interest to make something that will last as long as humanly possible, instead of creating something which has inherent design faults so that you have to replace it within ten years. And so it seems to me that if we could get Unilever or a big company, any big company, to redesign itself on the Future Guardian model. Can you imagine being a worker at a company where the workers are one sixth of the input into the whole company’s defining ethos and the way that it functions? You would go home that night feeling different about the world, I think. And then as a customer of that, knowing that you also potentially have a new word for customer.

Josiah: Well, I mean, we don’t like the word consumer in any context. Yeah. Fires consume things.

Manda: Yes. And chains bind things. I didn’t want to to grab all of this. I just thought it’s really interesting that you need to provide a model for people, because people in Unilever who get it and really push to change, will end up without a job if Unilever is still designed simply to grow and to provide shareholder value.

Josiah: The big question for a lot of these businesses is that they’re engaged with what used to be corporate social responsibility, now it’s ESG, and they have people who are very committed to those things. But the question, the reflective question they they rarely ask is, should we be making this thing in the first place? And that is the first question they should ask. So if you’re PepsiCo and you’re making sweet brown water, the first question should be not how do we reduce the water impact in India of making sweet brown water? But should we actually be making sweet brown water?

Manda: Yes, yes. All right. So final question. We’re running out of time. I have one last question and then we’ll open up to the audience. I think that systemic change only comes… That when we are in a situation, it isn’t just that we’re powering everything we do with fossil fuels -that’s bad. It’s not even that we power everything that we do – that’s not grand. It’s that we don’t know what we’re here for. We all know we’re not here just to pay bills and die, but we exist in a system where who dies with the most toys wins. And it seems to me that what you’re doing with your farmers and your networks is giving people a sense of being and belonging that does not exist just within the market economy. One, is that fair? And two, are you seeing that spread?

Josiah: Yeah, I think that is fair. I mean, what we use to frame our work is is agroecology, which I won’t go into in great detail, but essentially it’s a system of thinking about food that goes beyond the farm gate and involves people. Which is really, really critical. And I think fundamentally, what we hope and encourage people to do is to rediscover their place in the ecosystem. Since the enlightenment, we’ve we’ve spent our time othering ourselves from nature and forgetting that we’re part of it. And, you know, there are some fundamental kind of evolutionary traits that we have that that tell us so strongly that we are part of the world around us. The fact that we see more shades of green than any other colour tells us a lot about where we evolved, and that we have an intrinsic ability, even if we haven’t been exposed to it, to understand what beauty looks like in a natural context. I fundamentally believe that. And I think we need to be reminded of our position within that system and be allowed to express it in our day to day lives, which which we don’t do because we are in metal boxes travelling around. We all do it, I do it, you know, it happens, but we need to be given the opportunity to get out of those boxes and remember that we’re part of this wider ecosystem.

Manda: Yes. Brilliant. Thank you. Okay, so we’re opening up to questions. We have a roving microphone. Stick your hand up. We’re recording this, so if you ask a question can you say your name and if you’re associated with some amazing group say that too. Yes. Claire.

Claire: Hi, I’m Claire Whittle, farm vet. I just have a comment from a question, but I like what you said before about fava beans. I remember seeing a grower in Scotland and I said, where do these go? And he said, oh, they go to Ethiopia and they make some kind of hummus. And then we go down the road and then we get chickpeas and we bring them back and we make hummus. So I thought that was an interesting concept. But I wanted to say, last time I met you, I said I’d got some split peas to make Bombay mix. And you said, don’t worry about it, Claire. We might be getting there. I was just wondering, you called yourself a middleman earlier, but you create extra products as well. And was this about adding value? Or is it about because you just really like it? Or why did you go down that route where other middlemen wouldn’t necessarily?.

Josiah: Yeah. So I mean, our guiding principle is to sell minimally processed whole foods. Interestingly, I mentioned the John Innes Centre in the last session, but the Norwich Research Park has all sorts of really interesting organisations doing really fascinating research. And we work with a group called the Quadram Institute, which is about food and nutrition. And they wanted to understand the best way to eat peas. How do you best eat a dried pea? The thing that we work with. And we came back to them after eight months and they’d done all these feeding trials, you know, where people eat them and they measure glycemic index, and they do all of this kind of work. And they’d processed them in various ways. They’d fractured them, which is how we often see peas in food products, broken down into protein and starches. They’d milled them in various different ways, and they’d fed them to people whole. And we said, well, what was the result? And they said, well, the best way to eat peas is whole. And that seems kind of fairly obvious, because that’s how we’ve evolved to eat things. And we said, oh, brilliant. So are you going to support a change process around eating them whole? And they said, no, no, no, we’ve got a research project that’s looking at how we mill them in such a way as it minimises the damage. Because that’s what the food industry requires. It requires a fraction that is very consistent, that can go into a food process and always yield the same result. So yeah, we’re interested in minimally processed whole foods, but also how we can minimally process them to add some value and interest. So the roasted pulses and the idea about developing a Bombay mix is that lots of people think they don’t like peas and beans, and then they have the snack and they think, oh, actually, I do quite like these. And then that might open the door to them, eating them in other ways and feeling less nervous about them. Yeah, exactly. Yeah.

Jonathan: Hello. My name is Jonathan from Haven Hills Field and Kitchen. We’re a small grower and producer of local food in Shropshire. I was very glad, incidentally, that this was about re localising, not Delocalising as I’d read. But anyway, revolutions probably rarely involve the government that’s in place. But given that we need to effect a sort of revolution, what are the sort of three sort of or top interventions that you think a government could put in place to help us on this path towards re localising the food system?

Josiah: Yeah. Okay. Just three. Well, I think one of the things that we could start with is radical political reform. We need the people that we vote for to represent us, as the first past the post does not do that. I mean, this is quite political, but I think if we have proportional representation, we’ll get much better local representation, and we’re more likely to get effective change at a local scale. I think government needs to look at its own purchasing as I mentioned in this previous session. Public procurement is a really powerful tool for affecting cultural change as well as agricultural and agronomic change. And there’s a really interesting example from Denmark, Copenhagen. Copenhagen City identified that they had a real problem with groundwater pollution, which was going to be a real issue in the future. Nitrate pollution. They realised that it was farmers around the city that were contributing to that issue, and that by encouraging them to reduce the nitrogen they were applying to the soil, they could resolve the problem. But the most effective tool for doing that was to provide them a market route. So encourage the farmers to farm what was organic but essentially a low input system. Offer to buy that produce, make that available in schools and hospitals and any public context where they were supplying the food, and work out how to cook seasonally.

Josiah: So they they began training chefs who work for those institutions to cook. This began in about 2008. They encouraged farmers to convert to organic and reduce their input uses. And they created essentially a closed system that would affect the end point that they were looking for, which was less nitrogen pollution. The outcome is that more people now eat those foods at home because they’re eating them in their workplaces, in school canteens, and they’re normalising seasonal eating. They’re normalising cooking from scratch. And it’s had a really significant change in diet and land use around Copenhagen. And that was a political intervention. And our government, we’re in a very we’re in a different context, and it’s harder to make that work because of what’s happened to the way that public procurement functions. But we could do a lot with public procurement. Interestingly, I went on a tour of Copenhagen with some city councillors, three city councillors at the end of last year, and I asked them which political party they represented. They were all different political parties, but they were all clearly working together on this project. There were 19 political parties on Copenhagen City Council, and the point they made was that if it’s a good thing, why wouldn’t they all agree? And we don’t have a system that enables that to happen.

Ben: Hi, my name is Ben Wilson. I’m from Osnos. We’re a community kitchen garden and cookery school. I was really fascinated by your engagement of Norwich, especially given it’s a hell scape crop. Sorry. You know, like trying to translate that and get people re-engaged with a crop that’s really alien to them. I was wondering how much you found that there were class barriers. Because I think you need to call that. If there were, how you kind of navigated that, because I think it’s absolutely integral to call out there is a class system and the language and way to deal with that differs. And there needs to be different strategies. So yeah, I’m sort of interested to know your take on that.

Josiah: Yeah. I mean I think who we speak to and how and where and when are really difficult things. And we’re often accused of or we’re often told that we’re a middle class business for middle class customers. Looking at the demographics for the people that buy from us directly for our website, that’s not the case. It’s people that are interested in good food. And I think we have to make the mistake of assuming that because someone’s on a low income, they’re not interested. And this is the problem with the food poverty movement that uses redirected food waste. Is that why? Why would we have a system and why would that sticking plaster, which is a business that’s over produced something and is just going to dump it into a particular area, why would that be the best way of addressing inequality? I understand the sticking plaster and that we need to do something, but it’s a massively problematic approach. And yeah, I think we do need to recognise that we exist under these social structures. They haven’t gone away at all. And I think that just comes down to not having any preconceptions or prejudices about who might be interested in having that conversation. So with Norwich Farmshare, which very particularly is growing horticultural crops, they were on the edge of the city, growing on land that eventually became a new road. Which is slightly ironic really. And a park and ride car park. But they’ve moved into the city and they’re now they’re now working on a couple of sites which are in areas which you would think maybe people wouldn’t be interested, but of course they’re really interested. Because it’s growing food and it’s engagement with what’s happening and eating good food. But yeah, at policy level, I think there is a problem. And we do have problems with our preconceptions about who’s interested in what.

Speaker7: Have you got any suggestions for the hundreds of thousands of small households like myself, with a small garden, don’t know any farmers, don’t know any market gardeners, but want to help this revolution to take off. And talking about the last questioner, you know, don’t have all that much money, you know. You get the idea.

Josiah: Yeah I do. Grow beans is my answer always. But particularly grow runner beans or French beans. Beans that you can grow up a pole and you can eat them green and they’re delicious. You can eat them semi-dried, demi-sec, as the French would say. And they cook really quickly just as a bean. Or you can save them as dry. And that’s a great way of beginning conversations with your neighbours. What are you doing? Why are you doing those things? It does produce food and it’s relatively inexpensive and you can save the seed from year to year. I mean, I just say talk to everyone that you meet and tell them what you’re interested in.

Manda: I was talking last weekend to someone from Parents for Future, and they are about to hold a series of online trainings in how to hold complex or difficult conversations around all of these things. Of how to broach the kind of things where most people switch off and walk away and and keep people engaged and help to move the conversation. And they’re online. So I offer that, for what it’s worth.

Speaker8: Could you repeat that?

Manda: Parents for Future. And it’s ‘Parents For’ spelled out, because there’s also Parents 4, with the number four. So it’s Parents For Future.

Josiah: So I was going to say one other thing. I brought a prop. One prop, and it’s a surprising prop, because it’s Brazil nuts from the Brazilian Amazon. And it’s really just to make the point about what proximity is and what connection is and what closeness is. And a short supply chain doesn’t necessarily need to be very proximate. So my friend Jyoti Fernandes is the campaigns coordinator for the Landworkers Alliance, went to Brazil to understand how indigenous people organise. And while she was there, she met representatives from the Kayapo who have a territory of about 40,000km². And she said, what can we do to help you defend the forest? How do we communicate what you’re doing? And they said, actually, one of the most important things that you could do is to sell Brazil nuts for us. Because it will generate an income stream that will help us. It costs them about $1.2 million a year to physically defend the forest. They they have boats and watchtowers to to monitor for illegal loggers and gold miners and other mineral extraction. And by harvesting the Brazil nuts, which are wild, harvested from stands across their territory, it gives them a reason also to travel throughout the territory. The harvesting process, which happens over what is our winter, is also a site of cultural reproduction.

Josiah: So it’s a time when knowledge is shared between generations, when they when they wild harvest not just the nuts, but also medicines and fibres and other things that they’ll need through the year. And so we thought, when Jyoti came to us with this, how do we do this? Well, we’ve got this route to market that we’re using for UK farmers. We could also support the Kayapo, and we could communicate what it is that they’re doing in the Brazilian Amazon. And there’s a lot of tree planting going on, which is great. But there’s a bloody great rainforest out there that’s being cut down. And although the deforestation rate has slowed since since Bolsonaro left office, it’s still being cut down. And just let’s not chop that down to start with. And if we can find ways that are relatively inexpensive of reducing that deforestation pressure, by taking soy out of animal feeds in the UK, that will be a good starting point. And we’ve written a report called Soy No More about what effect on the food system the removal of soy and animal feed would have. And it’s radical. But also supporting those communities that are, as far as is possible in any system, working more harmoniously with the world in which they live in.

Manda: Brilliant. So we can get those online?

Josiah: Yes, you can.

Super get them online. Right? We have so run out of time. Thank you everybody. Particularly thanks to Josiah. And we’ll be starting again when Jenny?

Speaker9: Yeah, at 2. Thank you Manda. Thank you Josiah. That was great.

Manda: Thank you so much.

Okay, so there we go. That was our conversation. Huge thanks to Josiah for everything that he is doing. As I suggested at the top of the episode. Hodmedods is a living, breathing example of the change we need to see in the world. A really deliberate attempt to create new food networks that are outside the death cult of predatory capitalism and the industrial farming complex. Josiah and Hodmedods have a really well thought out theory of change and they are putting it into practice and it works. They are really opening up markets that were not there before. And this is not only good for the farmers and the growers and the web of life on and in the land. It’s good for the people who eat the food. And that’s us. You and me. Wherever you are in the world, there will be someone within reasonable reach who is endeavouring to farm or to grow like this. You just have to find them and then support them. And if there isn’t an equivalent of the good food partnership in your area. Maybe you could get together with some local people and create one. Because this is becoming increasingly urgent. The Stockholm Resilience Centre recently published more data on the planetary boundaries and how badly we’re exceeding them. I will put their picture and a link in the show notes, and please go and look, because it is genuinely terrifying to see the extent to which the boundaries are breaking.

Manda: And how much they’re breaking more than they were when the first paper was released in 2009. If you look at the foot of the image in the 6:00 position. P and N are massively over safe limits, and these are two of the three main chemicals that industrial farmers dump on the land. These are phosphorus and nitrogen. And the third one is potassium. Not all of the contamination of the oceans comes from farming. Some of it is from dumping raw sewage in the sea. But a huge amount of what farmers put on the soil is washed straight off into the rivers and then into the seas, where it is killing ocean life terrifyingly fast. We know each of us, that if we’re not part of the solution, then we are part of the problem. We also know that we need total systemic change and that this is not a linear thing. It’s not somewhere where we pull a specific lever and everything bad unravels overnight. We also know that throwing personal responsibility onto people is not always useful. Bp did not create the Personal carbon footprint calculator because they wanted to reduce our addiction to fossil fuels. They did it because they knew that if they could get us obsessing about turning off lights or using the washing machine a bit less, we would be so focussed on our own individual actions that we would not even look at the fact that what needs to happen is much, much bigger.

So all of that’s given. But we do have agency and we can use it. And when it comes to sourcing food for ourselves and our families, we have every good reason to use it. If you’ve listened to Ann and David in podcast 202, who wrote What Your Food Ate, then you will have an idea of how different is the composition of food grown in living soil compared to that grown in dead soils that have had NPK thrown at them. It’s not even great inorganic soil if that soil is dead. If you want to know more about that, I really do recommend their book. I thought I already knew more or less what it was going to say, and it completely reset and reframed my thinking. I genuinely think that if you read it, you will change how and what you eat. But if you haven’t time, here is my current advice. For you, for the living web around you, for the whole planet, insofar as you can, stop eating the products of industrial farming. For me, it’s not really about whether you eat meat or not. But yes, if your only source of meat is from industrial farms, then you do need to stop completely. But being vegan is not enough. If you eat soy products, or rice or beans or potatoes or whatever else you eat that has been grown in monocultures, farmed by tractors with chemicals, and then shipped across the world.

Monocultures destroy the soil. Chemicals are destroying the oceans. I know this is really basic. It’s Legoland for the food systems, but it’s the level at which we need to work. If what you eat was grown in monocultures, that needs to stop. You don’t want to be eating stuff that’s doused in glysophate. Really, you do not want that anywhere near you. You do not want stuff that has been grown with NPK and doesn’t have the micronutrients that your body needs. And in any case, food grown like that is destroying the oceans. So from here on in, find a local supplier and ask them questions about how they grow. There will be regenerative farmers and growers in your area who care about the land and who are doing their best to keep their heads above the financial waters of predatory capitalism. Help them. Subscribe to their food boxes. Join their community supported agriculture schemes. Make totally amazing meals and share them with your friends and family and neighbours and colleagues and explain why you’re doing it. We do not have to turn into food fascists, and particularly we do not have to tell people why and how what they are eating is wrong. The world thrives on positive reinforcement. So do what you love and celebrate it. And, as Claire Whittle said, the regenerative vet who was at the conference and who was completely inspiring and will be coming on the podcast in early 2024: change one thing. Watch what happens. See how you feel.

Let that stabilise and then change one more thing. If you do this with clear intent and a good heart, and if the periods of stabilisation are not too long, in a year or less, your gut biome will thank you. Your body will thank you. Your local community will thank you. The Land will thank you and the oceans will thank you. And then together we can build new frontiers of emergence. So that’s it. Go out and change one thing, and we’ll be back next week with a very different conversation, not about food and the land and how we grow what we eat.

In the meantime, enormous thanks to Caro C for the music at the Head and Foot. To Alan for the sound production. To Anne Thomas for the transcripts. To Faith Tilleray for the website, all of the organising and the conversations that take us forward, and for putting up with me being absolutely locked to my keyboard while I finished draft six of the book, which I handed in about half an hour ago. Yay! And as ever, enormous thanks to you for listening. If you like this, please give us five stars and a review and please subscribe. More importantly, if you know of anybody who really wants to understand the ways that we can connect to the land, to our food, and to the people who matter, then please do send them this link. And that’s it for now. See you next week. Thank you and goodbye.

You may also like these recent podcasts

Still In the Eye of the Storm: Finding Calm and Stable Roots with Dan McTiernan of Being EarthBound

As the only predictable thing is that things are impossible to predict now, how do we find a sense of grounded stability, a sense of safety, a sense of embodied connection to the Web of Life.

Sit with the River, Breathe Sacred Smoke, Love with the World: Building a Bioregional world with Joe Brewer

How can Bioregionalism supplant the nation state as the natural unit of civilisation? Joe Brewer is living, breathing and teaching the ways we can work together with each other and the natural flows of water and life.

Solstice Meditation 2025 – Sun Stands Still – by Manda Scott

Here is a meditation for the shortest night of the year – the time when the sun stands still.

It doesn’t have to be at the moment of the solstice, it’s the connection that counts, the marking of the day. And you don’t have to limit yourself to one pass through – please feel free to explore this more deeply than one single iteration.

Thoughts from the Solstice Edge: Turning the Page on a Dying System with Manda Scott

As we head into the solstice- that moment when the sun stands still—whether you’re in the northern hemisphere where we have the longest day, or the southern, where it’s the longest night—this solstice feels like a moment of transformation.

STAY IN TOUCH

For a regular supply of ideas about humanity's next evolutionary step, insights into the thinking behind some of the podcasts, early updates on the guests we'll be having on the show - AND a free Water visualisation that will guide you through a deep immersion in water connection...sign up here.

(NB: This is a free newsletter - it's not joining up to the Membership! That's a nice, subtle pink button on the 'Join Us' page...)