#204 Courageous Conversations – talking about what matters with Rowan Ryrie of Parents for Future

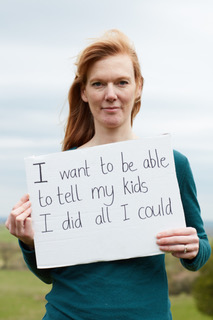

How can we, as parents, grandparents and anyone who cares about the fate of future generations, live our lives in such a way that when our children ask us why we didn’t do more, we can say with honesty that we did all that we could?

How do we help them to build resilience, to feel safe in a supportive community and in connection with the natural world so that as they grow, they can face the truth about the world they have inherited?

And how can we use our role as parents to create conversations that matter, not only with people with meet in our daily lives but also with those in positions of power.

These are some of the core questions that prompted environmentalist and movement-builder, Rowan Ryrie to co-found Parents for Future, a fast-growing group of parents who have come together to support each other in navigating the climate crisis and trying to secure a safer, fairer world for children everywhere.

Rowan says, ‘Together, we can be much more courageous than we can alone,’ and she’s brought this understanding to their latest project, ‘Courageous Conversations’. It’s a pilot project just now, but when the results are in next year, it will be spread out around the UK and then, if there’s funding, around the world, to give us emotionally literate tools to engage with the people we encounter in our communities of place, purpose and passion.

This feels to me to be right at the cutting edge of the emergent future we need to create. It’s grounded in a theory of change that makes sense in the realities of overall systemic change, while at the same time, understanding that shift happens one courageous conversation at a time, and that we all feel better if we can share our fears and build hopes that work for everyone. Rowan specifically wanted me to assure everyone that Parents for Future is not only for those with young children – or any children – if you care about the world we’re leaving to the generations that come after us, human and more than human, then do join. There are 28,000 members and rising, all around the world – and if there’s not a physical, location-based group near you, and you want to set one up they’ll help.

Coming up – Accidental Gods Online Gathering

Dreaming Your Death Awake – Sunday 29th October 2023

Episode #204

Links

Coming up – Accidental Gods Online Gathering

Dreaming Your Death Awake – Sunday 29th October 2023

In Conversation

Manda: Hey people, welcome to Accidental Gods. To the podcast where we believe that another world is still possible and that if we all work together, there is time to create the future that we would be proud to leave to the generations that come after us. I’m Manda Scott, your host in this journey into possibility. And I’ve just finished speaking to someone who is working right at the edge of change and theories of change, grounded in creating that future that we would be proud to leave behind. Just before we get to that, I want to remind you that there’s an online Accidental Gods gathering on Sunday the 29th of October. Dreaming Your Death Awake is four hours of exactly what it says on the tin. I absolutely believe and want to share that we cannot fully live until we learn to fall in love with the reality of our own death. So we’ll be exploring that, the ways we might do it and where it might take us. If that sounds like something that would be useful to you, then do come along. Details are on the website: accidentalgods.life, on the Gatherings tab. And I’ll put a link in the show notes. And then this week we’re talking to Rowan Ryrie, who is an environmentalist, a climate activist and a movement builder. And specifically is talking to us today in her role as one of the founders of Parents for Future, a growing group of parents and others navigating the climate crisis and trying to secure a safer, fairer world for children everywhere. Rowan is quoted on the website as saying ‘Together we can be much more courageous than we can alone’. And she and the others have brought this understanding to their latest project called Courageous Conversations. It’s running as a pilot just now, but when the results are in early next year, the plan is to roll it out around the UK and then the rest of the world.

Manda: With the aim of giving people emotionally literate tools to engage with those they encounter on a daily basis in their communities of place, of purpose and of passion. This feels to me right at the cutting edge of the emergent future we need to create. It’s grounded in a theory of change that makes absolute sense in the realities of overall systemic change, while at the same time understanding that shift happens one courageous conversation at a time, and that we all do feel better if we can share our fears and build hopes that work for everyone. But what we so often lack are the tools to know how to strike up conversations in ways that are not going to trigger the people we’re talking to, or ourselves, so that we can hear and be heard. Rowan specifically wanted me to assure all of you that Parents for Future is for everyone, not only those with young children or any children. If you care about the world that we are leaving to the generations that come after us, human and more than human, then do join. There are 28,000 members and rising, all around the world. And if there isn’t a physical location based group near you and you want to set one up, they will help you to do that. So with this as your inspiration, people of the podcast, please do welcome Rowan Ryrie of Parents for Future.

Manda: Rowan. Welcome to the Accidental Gods podcast. It is an absolute delight to have you on this morning, and thank you for fitting in at quite short notice when we had a cancellation. I am enormously grateful.

Rowan: Thank you for having me.

Manda: You’re welcome. How are you and where are you this morning?

Rowan: I’m well, thank you. The sun is shining this morning, which always helps. And I’m in Oxford this morning.

Manda: Yay! Oh, centre of learning and dreaming spires. Fantastic. Thank you. So you are one of the co-founders of Parents for Future, which seems to me one of those things that has emerged relatively recently. And yet you have 28,000 members, probably more, because I read the website a while ago and it strikes me that you’re probably getting more every day. Tell us how you, Rowan, came to be the person who helped to start Parents for Future, and then tell us a little bit about what it is and what it does.

Rowan: Okay, I shall try and not make this too long winded, because there’s a lot to say. So Parents for Future started in early 2019 when the school strikes movement was really in its ascendancy. But my story starts a little before that. So I have two young children now. They are now nine and five, but back when parents for future started, they were very little. I am a human rights and environmental lawyer by background, so I’ve worked in human rights and environmental law spaces in different charities for some time, and I’d been doing that before I had the kids. And then when I had my second daughter particularly, I had a little bit more space to raise my head from those kind of early years of parenting. I think I was just trying to understand how to be a parent with my first child, there’s a lot of steep learning curves to work through. And then when my second daughter came along, it was around about the time that my first daughter was due to start school, and that threw me into a phase of needing to think ahead, needing to think longer term about her future. And suddenly I was having to make decisions for her about what she was going to need to learn and what the future was going to look like for her, and what she would need to understand and to learn to be equipped to survive in that future.

Rowan: So I think that applying for schools is often a big milestone in most parents, but I certainly took it on the deeper end of the spectrum. And that threw me into thinking about my background in environmental law, my background in human rights, and then to join the dots to climate. And I’d never worked on climate. I’d worked on other human rights and environmental issues, but climate always felt a bit too big and a bit too scary and like didn’t have enough expertise to come into the climate space. But having young kids, I sort of realised that maybe just having those children and loving those kids and caring about their future was enough of a reason for me to engage, and that that was enough for me to be able to speak out and start to think about engaging around climate. And I also realised that in contrast to the kind of long term decision making that to me is inherent in parenting, in our political spaces all we see is short term decision making. So is there a way to join those dots and to bring some of that long term decision making, that comes from a place of love and care and compassion into political spaces? And then various things happened through that autumn of 2018, when I was thinking about lots of these pieces.

Rowan: Greta started the school strikes movement in August of 2018, Extinction Rebellion had their first big actions in the autumn of that year, and the IPCC released a big report saying that we had at that point 12 years to save the world. And that number was the same number of years that my eldest daughter would be in school. So it really focussed my mind and made me realise that I, as a parent, needed to step into action on her behalf now, because by the time she was of an age when she would be able to do anything about it, it would be too late. So it felt that there was a real kind of moral imperative to step into action as parents. And so was there a way we could help more people understand that? And then the school strikes came to the UK in the beginning of 2019, and I saw that as a moment when if the kids could do this, if these amazing, inspiring kind of young teenagers could step way outside their comfort zone and organise protests, then surely I as an adult could do that too.

Rowan: I wasn’t somebody that saw myself as an activist. I was a lawyer and had fallen deep into that good girl way of thinking. Of, you know, needing to stick by the rules. But it felt like that was an opportunity for me to kind of step up. So I went along to the first of the school strikes actions in Oxford, which was brilliant. The energy was just infectious, really, really beautiful. And kind of committed at that point that I was going to find a way to bring parents along on this journey as well, and connected with others who had had similar ideas, online. And together we formed parents for future in the UK. And I connected with others around the world and with others also formed Parents for Future Global. So I started to organise nationally and globally and locally in Oxford, all at the same time. Which made for some very busy years. But there was a lot of energy and a lot of people coming up with similar ideas. And then it’s been trying to create connectivity between what’s happening in different spaces and structure around that. And where we are now. It’s moved on a bit from those origins, which was trying to get parents on the streets alongside youth activists. We’ve realised that engaging parents needs quite different approaches to engaging youth activists.

Rowan: The Covid pandemic kind of intervened and made protest impossible for a long time, and the government has done their best to make protest impossible also. And that’s been a big factor in making protests something that a lot of people are very, very nervous about. Because the government are trying to make it seem that protest is illegal, which of course it isn’t. We are allowed to protest, but it’s something that a lot of people are very afraid of. So we’ve shifted from a strategy that was very protest focussed in the early stages, into much more of a kind of organising approach, of trying to build community. So the way Parents for Future in the UK is working at the moment is we are focusing on two pieces, which are building power and building resilience, and we do that through community. So we do that by connecting people; we’ve got a national online community, which we’ve just shifted how we’re doing that work online, so it’s a bit better supported. And we’ve also got a network of local groups, and there’s about 40 local groups across the UK at the moment and growing fast. So we’ve got lots of new people stepping up and wanting to engage in different pieces of this work.

Manda: Oh, Rowan, there is so much in this to unpick and go into. Thank you. Really thank you. Because it feels to me, listening to the parents in the family, the younger members of the family who now have young kids, and others of that age, that it’s so frightening looking ahead that the tendency to just want to go into ostrich mode and just deal with the issues of today, which as a parent – I am ever in awe of anyone who’s ever been a parent. It looks like the single hardest human task imaginable. And simply that would occupy all of my bandwidth, I imagine. And yet you have two young children and you are finding activist space. You seem like an activist to me, however you self-label. Can we take a bit of a step back and just have a look at what pushed you to human rights and environmental legal concepts before all of this? Did you come from an activist family? These are activist things. You could have been, I don’t know, a criminal lawyer or a house conveyancer. You’ve got a legal degree, you can do a lot of things that are propping up business as usual in the existing neoliberal, predatory death cult. And yet you were already doing things that are nibbling at the edges of that. What drove you in those directions?

Rowan: Great question, and I’d love to come back to the emotional bandwidth that parenting takes as well.

Manda: Go with that first then.

Rowan: Okay. So we try very hard to build emotional support into the way we organise with parents for future, because of that. Because it can just feel terrifying to look at what the scientists are telling us is going to happen and connect that to the love we have for our kids. So we do a lot of work to make sure that we build emotional support in, right from the very beginning of how people join Parents for Future.

Manda: What sort of emotional support?

Rowan: We work very closely with the Climate Psychology Alliance, and we have some people that are trained by the Climate Psychology Alliance that have helped us work out things like the joining calls that we have. We have spaces there where people can just share how are they feeling. How does this feel for them? And then we have specific spaces online and spaces where we have calls for people to share how they’re feeling and how they’re processing this now. And we really find that by connecting with other people who are dealing with the emotions of being a parent in this moment, in this climate crisis, that actually frees up a lot of bandwidth for people to step more into action. Because they’re spending less time panicking and less time worrying.

Rowan: So it’s quite remarkable actually, seeing how providing that connectivity, helping people feel less alone with their fears, that that enables them to do more. I’ll come back to your actual question, which was how did I bring law into this? Or where did that come from? So yes, activist family I’d say. And yes, I accept the label activist wholeheartedly now. I didn’t originally, but I think showing people that activists take all shapes and sizes is important. My family, yes, they were very political in different ways. My dad spent a lot of time thinking about alternative economics. So debating alternative economics and debating the fact that capitalism really was a problem, was completely normal through childhood.

Manda: Who’s your dad? Is it someone whose books I’ve been reading?

Rowan: He’s no longer alive. And no, he didn’t get round to writing books, but he spent a lot of her time setting up local economic trading systems, which was all the rage back in the kind of 80s, 90s. And is a lot less talked about now.

Manda: Whereabouts in the country? Was he in Bristol with the Bristol Pound or Totnes or?

Rowan: No, he was in Canterbury with the Canterbury Tales, so there were lots of them around. So a lot of that conversation around capitalism and around the fact that money wasn’t a given and that there are different ways to exist in the world and different forms of value. And how can we think about Localising and Globalising? So I grew up discussing that and then grew to really not want to discuss it anymore, because it was so much part of the bread and butter of my family. So economics was not my calling. My mum comes from a different perspective. So she’s written books around forest gardening and organic gardening and horticulture permaculture, so there’s that strand also. So kind of connection to nature in different ways.

Manda: We need the name. I’ll put a link in the show notes. Where would I find your mum’s books?

Rowan: Charlie Ryrie. So she’s written about various of those pieces. Not so much recently, but for a long time. I grew up in Stroud, where there’s a strong activist community, alternative community. So people that weren’t necessarily seeking high salaries and trying to kind of make themselves important in conventional systems, was completely normal. And I really appreciate that now. I really appreciate that both of my parents did not value the things that the capitalist system teaches us to value. They had actually very little respect for most of the kind of conventional forms of hierarchy and salaries et cetera. So, yeah.

Manda: It’s the difference between extrinsic and intrinsic values. We were speaking to Ruth Taylor a few weeks ago, and the Common Cause Foundation has done all of that work; that the more you value intrinsic values of community and connection and resilience, the less you need the external validation of a high salary and a big car. And you grew up with that, which is just glorious. And I’m guessing you’re bringing your kids up with that too, which is also glorious.

Rowan: I’m certainly trying to, yes. I find myself running interference on the education system constantly, which is interesting.

Manda: How did you, as a legal student, find that? Because one of the things we find in economics is that as students come in and are taught in the orthodox ways, that money is value, they become more psychopathic basically. And I’m guessing that in the legal system you were then bombarded with extrinsic valuations of who you were. How did you navigate a route through that that kept your sense of self and your intrinsic value systems intact?

Rowan: So law wasn’t my first degree. I did a law conversion course after doing a degree in archaeology and anthropology. So I spent three years focusing on archaeology and anthropology and understanding how communities work and how different types of communities can have really different values and can work really differently, in different parts of the world and in different times. And it’s taken me some time of working on climate, of not really understanding how that fits into my work that I’m doing now, that archaeology did feel somewhat divorced from the climate work I’m doing now. But increasingly having an understanding that societies do collapse feels relevant. That absolutely what comes through in studying different parts of ancient civilisations, you understand that those civilisations are not here anymore. And so I have that kind of deep time perspective, I think, that helps set some of what’s going on now in context.

Rowan: So I studied that first and then spent a year working in various charities and then did a law conversion course. Always with the intention of bringing law back to the charity sector. So I went to go and get the legal qualifications, because I knew that that would have weight when I brought that back into charitable spaces. And human rights and environmental law were both always interests of mine. So I was also doing lots of voluntary work whilst doing legal training, with organisations like Global Witness, who do fantastic work. And think that helped to keep some perspective on what it was that I wanted to come back to. I also deliberately didn’t choose to go and train with one of the magic circle law firms, because thought I wouldn’t escape if I did.

Manda: Is that what they’re called?

Rowan: That’s what the big, most prestigious law firms are known as the magic circle law firms. Yes. So I trained in a law firm that was fine. They’re very nice culture for a law firm. And did things like education law and public sector law, as well as insurance law and reinsurance law and some of the harder end of the legal work. But left as soon as I qualified as a solicitor, having done all of the kind of years of legal training and at that point stepped out to go and work for environmental spaces.

Manda: Right. Brilliant. Again, there is so much in that that I’d like to unpick. So top of the list of the things that are coming up for me, is you said you were running interference on the education system. And and I’ve just handed in draft six of the book (yay!) Where I was exactly looking at a bunch of young people going, education is gaslighting us. Do you really think that we are going to have a future with a mortgage and a car and 2.5 kids and a golden retriever and a job that we have for life? No. You know, it would be more useful for us to come and do whatever you guys are doing. And yet, what brought you into this was you planning ahead school for your children. If it is the case that we are in the middle of civilizational collapse, and I think you and I would probably both agree on that. And if it is the case that this is the first time in human history where the evolution of AI means that the usual collapse pattern, of descent into relative technological inadequacy and a rebuilding to something new, is not going to be replicated necessarily. That AI may bounce us into something completely different. First of all, is that premise one that sits with you? And then if it is, what is your view on how we are helping the minds of young people to develop? Which is what education is for, but what it has been for and what it could be for and what it might usefully be, are, as far as I can see, a bunch of entirely different questions. Where do you go with that as a concept?

Rowan: So yes, I think I agree with that premise. I find some of the conversations around AI quite difficult to engage with, because I find it difficult to look at two existential threats at once. And think a lot of people struggle with that. Kind of looking at climate crisis and looking at AI and understanding how to process that, and how to understand what that looks like. But I think on a personal level, just making decisions about my kids future really does throw into stark kind of light, how do we best support our own kids and how do we best support the kids around us? I’ve had a lot of conversations about different types of education, different types of schooling. The role that creativity does or doesn’t play in our education system. Usually doesn’t. And have currently landed on my kids are in mainstream school, a very kind of little low pressure primary school around the corner from my house. So they’re very connected to the community that we’re part of, and that felt important. But there’s there’s often a temptation to look at other education systems, but it’s difficult to balance that with the work I do that feels important, and that I wouldn’t really have time and headspace to think about different education models whilst doing this. There’s no perfect solution and I think that’s true for most families. There’s no perfect way through it. To me, the thing that feels most important is building resilience. So helping our kids to be resilient as people. And to build community resilience also.

Rowan: So to help them feel really connected to themselves, so that they know who they are and what it is that’s most important to them, and what resonates with them in the world, so that they trust their own understanding of who they are and where they are. And to connect to the communities around them so that they feel really well supported, which our schooling system doesn’t always do effectively. And to connect to nature. So to connect to the natural environment. So that’s been absolutely my starting point whilst the kids have been really little. And think this should be the starting point for thinking about how do we talk to our kids about climate for example. While they’re small, we don’t. We talk to them about nature, and we help them to love the world around them and to feel part of this beautiful web of life. And if they’ve got that really deep sense of connection to nature, then that’s going to stand them in good stead long term for whatever else it is that comes. But I think that connection to self, that connection to community and that connection to nature and the natural world feel fundamentally important. And I would agree that our schooling system doesn’t always do a great job of embedding that. And so how do we as parents support kids around whatever else is going on in their life, so they have that?

Manda: Yes, because I am aware that the education system is not what it was when I went through it. However, watching from the outside, let’s say standard business as usual schools, definitely don’t seem to be for grounding the things that you just said. And they do seem to be still locked in a mindset where people are competitive. Survival of the fittest means that you are all in a zero sum game. And all of the things that we know not to be true, but it’s really hard to change the system. Is it possible, is it something you’re looking at, that parents for future would begin to create local schooling hubs where you take a different set of values and bring people together. And home schooling again, the little I’ve seen of it, looks incredibly hard. But friends of ours recently moved from where we are back to Forest Row, because there’s a Steiner school. And it’s a whole different ethos, and their kids are thriving in ways they totally were not in the standard school system. And there isn’t a Steiner school everywhere, and they’re quite expensive. But if you’ve got 40 local groups, can you then begin to create hubs where your kids learn the things that we believe matter?

Rowan: So there are definitely people within the Parents for Future community that are doing that. And there’s a lot of amazing models of alternative education, that’s not just something like a Steiner system, but where you have groups of families coming together and you can have kind of collaborative home education models that I think are really interesting, and sometimes lower cost. I think the issue with a lot of this is it’s really inaccessible to a lot of families. A lot of families just don’t have the financial ability, often, to access any sort of education beyond the mainstream. The pressures that we have within our current society mean that people are needing to go and earn money to pay the bills, which are increasing month on month at the moment. So what we’re focusing on, I think a big focus for Parents for Future, is reaching beyond the eco bubble at the moment. Is trying to reach beyond already engaged audiences and bring more people into feeling that they can engage around climate, that they can care about climate in some way. And for that reason, one of the next pieces we’re going to be doing is engaging through school communities. So not necessarily creating alternative school communities, but empowering parents who sit around schools. Parents are an important part of a school community and are often overlooked by the climate groups that are doing ‘schools engagement’.

Rowan: So we’re figuring out models for engaging parents as part of school communities, and that will mean that parents can be organised and empowered and can have agency to engage on a range of different issues through their local area. So that might mean that they end up working with schools to bring in more outdoor education, to think about fundraising, to think about how they can shift the energy system that that school is using. Or to campaign with a bunch of schools together to try and shift policies within an education authority, or various other campaigns. But I think one of the other reasons that we’re wanting to engage that way through school communities, is that school communities are really diverse. So in a mainstream school system, you do have a real mixture of families from all sorts of different socioeconomic backgrounds, as well as other sorts of diversity. And so if there’s ways that we can help parents feel able to go and have conversations with others, through school communities, about what they care about; about climate, about economic issues, and make the connection to what’s happening in the climate crisis. Then potentially we can help more people find ways to step into into action.

Manda: Okay. Is this what you mean by running interference on the school system, or is that a slightly separate thing?

Rowan: I think my running interference is more on a small scale. It’s more about within my own kids and sort of looking at the curriculums, looking at some of the things that they’re being taught and finding ways to question that and finding ways to bring up those conversations. And on a small scale, I do fairly regularly go and encourage the teachers in school to let me come and give you a lesson, let me come and share about something. Which actually they’re really receptive to, which is great. Often they’re very happy to have some more resources or have some more suggestions.

Manda: I bet they are.

Rowan: Teachers are doing their best. Teachers are amazing and often very willing to take on board suggestions, if parents are offering to go and help bring some different content through. But they’re really hamstrung by the system.

Manda: Well, that’s what I was thinking. The more the command and control from the top is is layered over by people whose only understanding is is command and control, the less freedom they have. But again, the teachers I know are very, very creative at finding the gaps in the command and control system. Let’s take a step back and have a look then at what you said previously about engaging through the school system. Because of the diversity that’s there, because that’s where the people are. Instead of creating little bubbles of an echo chamber, you’re moving out into the school ecosystem. How are you planning to do that? What are the strategies that you’re involved with that might work? I’m guessing you’ve got some good strategic people who understand the school system, and you have plans of how to do this. Insofar as you can, can you tell us what they are?

Rowan: So yes and no. We are at an early stage of coming up with those strategies for the schools piece specifically. But one of the bits that we have started launching and testing at the moment, is around climate conversations. Or kind of courageous conversations, of how to help people talk about climate in different contexts. And at school gates is a key one for our audience. And actually having conversations at school gates can be really terrifying, because these are people that you don’t know very well, but you will probably see every day for quite a number of years.

Manda: And their kids are interacting with your kids. And if you piss them off, that can have ripple effects that you will never see. But it could be disastrous. So yes. Right.

Rowan: Yes. So it’s quite a sensitive space. And how can we help people find ways to have conversations in some of those spaces, or in other spaces I think. Conversations is a strand of work that we’re exploring. It doesn’t have to just be through school communities, that could be with your family, with colleagues, with other people in your community. Et cetera.

Manda: The people that you meet in the supermarket queue. How are you doing this? This sounds like something that could expand way beyond schools. Definitely. And is possibly one of the tipping points that we’re looking for from a narrative structure. If we can begin to have the conversations that dismantle the consensus of business as usual, then the tipping points happen. You’ve got the Climate Psychology Alliance. Did I get that right? So presumably they have ideas of how to frame conversations in ways that are not going to trigger people’s amygdalas as soon as you open your mouth, which I have a tendency to do. So how do you frame these conversations? Is this something you’ve begun to get onto the ground?

Rowan: Yes. We’re doing this in partnership with an organisation called Larger Us, who are helping with a lot of pulling the training together. And then we’re making sure that we’re bringing the people to that training and thinking about how we can best support them and how we can scale it. We’ve had a lot of demand from within the Parents for Future community for a long time, of people saying how do I talk about this? And there’s also some very interesting research around the impact that you can have with conversations. So my interest in this specific piece of work came also from studying ways that organising has been impactful in other parts of the world, particularly in the US. So there’s a model that’s been used in the US called Deep Canvassing, which was developed in California and was certainly developed on Lgbtq+ rights. So to help people go and have conversations on doorsteps around issues that were quite polarising in that context. And I think it was after a vote had been lost around gay marriage in California at that time. But I could be corrected on that.

Manda: And that was then used in Ireland to really good effect during the two referendums, wasn’t it?

Rowan: I think it’s a similar model. Yeah. So I was interested in how we might be able to use that in the UK around climate, and other organisations have been exploring similarly. I know XR actually did some work around using deep canvassing and getting people to go out and do doorstep work last year or the year before. So they’ve done that at some scale. And then we got in touch with Larger Us who were also thinking about this. And they are an organisation that thinks about psychology. So they’re thinking about behaviour change and about how you might be able to use different aspects of psychology to shift behaviour change around different issues, and to help people connect with values across different issues. And they come from very much a research perspective, so they had a lot of the deep thinking around how you might do this. And they were particularly compelled to think about conversations, because there was a study that was done a few years ago by Climate Outreach; Britain Talks Climate, a big piece of research about how different parts of the population think and talk and engage around climate issues. And part of that research showed that 57% of people in the UK talk about climate rarely or never. So there’s this huge silence around climate.

Rowan: But we also know that a lot of people are concerned about it and do have their support for climate and climate issues and climate action, but we don’t talk about it. And that Britain Talks climate research also kind of broke down the population into different demographic segments, of which only 13% are the activists. So there’s this group called Progressive activists in that research, and that’s about 13% of the population. Whereas about 70% of the population under that research could be persuaded to take action, but they’re not really doing very much at the moment. So there’s this huge group that could be engaged, but there’s this silence. And I think another piece of research that has really pushed us to do it from a parent perspective, was there was some research last year, again in the US, that showed that in the US, parents of school aged kids are one of the most socially engaged demographics. So out of all of the different populations that they looked at, parents of school aged kids have this really strong social network and are quite likely to write to elected representatives and quite likely to volunteer. But potentially, well, this research showed in the US, were less likely to vote than many of the other demographics.

Manda: Because they thought there was no point or they just didn’t have the time?

Rowan: I think so. Time is a big barrier. Time is a huge barrier to action for parents, and that’s something that we work at quite hard, to break down actions into something that’s manageable for parents who are feeling perpetually overwhelmed. But there’s some quite interesting potential there for engaging through parents who have this social connectivity. So the way we’re doing it is we’re running a pilot program this autumn. So we’ve just started it a couple of weeks ago with Larger Us coordinating it. And it’s us and three other organisations that are also doing this pilot, and that will provide us with some really interesting insights into how different populations use conversations and then what the impact of those conversations is. We had a Kick-Off call a couple of weeks ago. All of it’s oversubscribed so far, so I’m hoping that we get through this with some really good learnings and we can launch it on a bigger scale next year. We do need to figure out how we fund that. So we had a kick off call a couple of weeks ago. Next week we’re running a workshop which will run through some nuts and bolts of how you have these conversations, and get people doing some role playing, of practising having some of these awkward, courageous conversations with different people. And how might you open that conversation? How do you find a way to connect with somebody else and help kind of connect about something that they love? Which is always a good way to find a way to understand what is it that they care about. To be able to listen and understand what they care about, and then to help make that connection across to some of the issues that you’re wanting to talk about, which is what the deep canvassing model teaches how to do.

Rowan: And then once we’ve had that workshop, it’s going to go into very small groups for a six week challenge period, of getting people to go out and do this work. Of go and have conversations in your community and then come back and share how it’s going. And that’s a combination of we have an online platform that we organise through at the moment called Mighty Networks, so we can provide support there in real time. And that will also mean that the people that are doing this in this kind of small supported group can share their experiences with our much wider community, so we can learn and hope that there’ll be some organic pickup quite quickly. But there’s also a very strong monitoring and evaluation piece built in, because it’s a pilot program, so that hopefully we can get really good data and learn what is working. So that hopefully we can scale it next year. That’s what we’re hoping to do. So there’s lots of ingredients.

Manda: So if anyone out there has some funding. What kind of scale of funding? You may not be able to answer this, but are we talking tens of thousand, hundreds of thousands to get this scaled?

Rowan: I think it depends how big we want to go, but I think if we want to really scale this really fast, then I think it’s going to need more substantial funding. So hundreds rather than tens, but it’s all helpful. And this piece of work, we haven’t had any specific funding for this so far. We’re doing this based on other funding that we’ve got that’s running for other projects, and we’re prioritising this as a model, to be able to deliver on some of the other commitments and work that we’re doing. But this is a piece that we want to write up as a specific project and get some funding for, hopefully together with other organisations. Because although parents have this social connectivity, I think this is a model that lots of organisations would be interested to pick up and run with.

Manda: Yeah, totally. This this could be a workplace thing, a family thing. I mean, anyone who’s interested. And those numbers you gave us, so there’s 13% consider themselves activists. I wonder was that data collected before the government decided you’d get ten years inside for being a nuisance, which probably dampened people’s activist fervour a little bit. But then 70% are concerned enough, and I don’t know if there’s a theory of tipping points, I don’t really believe the XR numbers, because none of the tipping points we’ve had in our culture so far have been changing the system. They’ve been expanding the franchise a little bit, which is an entirely different thing to Guys, We’re in the middle of civilizational collapse and we want to build something new. That’s a whole different conversation. So the tipping point would need to be greater. But 70% is a tipping point. It has to be.

Rowan: The tipping point that we refer to as 25, I agree that if you look at really small numbers, like 3%, I think you’re going to need more than that to be able to get people to change the system.

Manda: But 25% would be… It begins to become something that has uptake in the general media, I would think, by the time it gets to being 25%.

Rowan: Yeah, I think there’s not going to be any individual number. You’re not going to get to one specific number.

Manda: No. But the kind of concept of tipping points, so it trickles, it trickles, it trickles, it becomes a flood has to be somewhere. 30% sticks in my head, because I think that 1 in 3 people really getting this, then becomes something substantial.

Rowan: But I think the key for any of these tipping points is making our concern visible. Because there’s so many people that are concerned already. But if we sit in our homes being concerned and often not even talking to our family about it, then that doesn’t have any impact at all. So how can we make our concern visible?

Manda: And your theory of change, as far as I can tell, is you give people a sense that they’re not alone. You let them know they’re not alone. You let them talk to other people who are equally concerned, and then you give them the tools to have the conversations and find who else is silent and concerned. So this is largely what the Climate Majority Project is aiming for, even just with its name, that most of us are desperately concerned and most of us have no idea what to do with that concern. So we we hold it inside. And all of the psychology says the more you internalise a terror and don’t give it space, the stronger it gets and the more shut down we become. So in the conversations that you’re having, let me take a step back to this pilot. Is this all happening online? Is the first question.

Rowan: The training is, the conversations aren’t.

Manda: Obviously the conversation is happening at the school gate, but the training is all online.

Rowan: Yes.

Is it UK based or is it worldwide?

Rowan: This is UK at the moment.

Manda: All righty. But in the end…

Rowan: In the end it could scale for sure. Yeah, conversations potentially could scale. I think climate organising looks very, very different in different contexts and the ways people are working has to be hugely context specific.

Manda: Yes, yes. So a village in Africa is going to be very, very different to a village in Oxford. But still, if there were people who were given the tools and the capacity to localise what they were doing, then this is something that could be scaled globally without effort. If we have communities of place and of purpose and of passion, the last two don’t have geographic boundaries, as you’re already discovering I’m sure. I’m sure there are people from all over the UK coming into this. So you do the training online. If you and I were were doing this, how would you establish? We’ve met at the school gate. Our kids are busy kicking a ball around, we’re waiting to go home. What do you do to kick off the change from let’s just talk about the weather, or the latest sports scores, or the horror of politics to something more profound.

Rowan: I think I’m going to have to come back and show that to you another time, because I’ve not done the training yet. That training is coming in next week and I’ll be on that training alongside others.

Manda: Darn we should have we should have waited a week! Never mind. You’re coming back to tell us about this next spring when you’ve got this going.

Rowan: I’d love to come back and and can model it for you another time. But yes, I’m not going to pretend that I know how to do that yet, because I’m about to be taught.

Manda: Okay. That’s fine. I am genuinely interested because I have this sense that the kinds of conversations that we have with the people, not just at the school gate, although clearly I’m hearing you, that parents are kind of forced into being social because kids have to be social. It’s going to be interesting. I imagine when AI tutors become a thing and kids are then locked to learning from their screen, but that is probably a whole other conversation. And I hear you about not wanting to overlap our apocalyptic visions. However, I do have a bit of a question that I think your particular upbringing will address. Which is we know it’s not just about the climate. This is a climate and ecological and sociological and cultural emergency. And yet already we found in this conversation that we all have limited bandwidth. It is really hard to be concerned about the AI apocalypse and the climate apocalypse at the same time, or even to look at one of those and to realise that our political system is broken. And yet change has to be systemic. We can’t fix just one area of this. How do you personally cope with the balance between compartmentalising and generalising. Does that make sense as a question?

Rowan: It does and I think imperfectly is probably part of the answer. Your point about AI tutors becoming a thing is interesting, and I think one of the reasons that this conversations piece of work feels so important, is that we have all got so bad at having conversations in real life with people that are outside our usual sphere, of same group of people, or similar thinking group of people. So just having conversations, I think is almost quite a radical thing to do now. To go and put yourself in that awkward position of going and having conversations with people that you don’t already know. Which is a kind of sad reflection on where we are as a species and a society with an ability to connect with others. I think that Compartmentalising generalising piece, I think the way I respond to it at the moment is coming back to quite a lot of personal connection work and deep connection, nature connection work. To help me hold in my self true to what it is that I need to be doing in this moment. What’s the work that I need to do, to try to not get too broad and too thinly spread, to focus on everything all at once. But what is it that’s mine to do? Which is a question I find very useful to come back to.

Rowan: I think it is really difficult to look at everything all at once. But yes, it’s imperfect to do that also. I Think there is absolutely a need to recognise that this is all interconnected, but that there are some systems that sit underneath a lot of this that is interconnecting many of these pieces. There’s the capitalist system. For me, the legal system plays an interesting role in connecting how we make decisions. And what’s the role of the governance structures that sit around our society? So looking at that kind of systemic level, I think is really interesting. But yes, I think we also have to allow ourselves to stay sane enough to function and to be able to keep going on some of these different pieces. And for that resilience and emotional support and nature connection are really important for me to be able to just keep functioning, keep going.

Manda: Yeah, and finding that interface between where our hearts greatest joy meets the world’s greatest need, which would be for me a framing of what is mine to do. That, again, is a skill that a lot of us are not given, because we’re told our heart’s greatest joy is doesn’t matter, and the world’s greatest need is for us to accumulate capital. Which clearly is not true. But even challenging that can be a step out of the mainstream that feels insecure. And also we’re often challenged on it. I read a piece that’s not yet been published, so I can’t mention the author, but it was a very thoughtful, very long 6000 word piece on structures within philanthropy. And they were talking about having been at a meeting where someone stood on the stage and said, not dissimilar to what you just said, that the current structure is falling apart. We here are the issues, here are emergent possibilities of things that we could do. And a significant section of the audience didn’t want to hear the first bit. The kind of ‘Don’t look up’ concept of no, don’t tell us everything is falling apart. And another significant section of the audience said you’re not being realistic with the answers, because basically global capitalism is the only game in town and you can’t suggest anything beyond it. And these are people who are really switched on and have come along to something, intending to be an agent of systemic change. So goodness knows how that would go down in the average random section of the population.

Manda: Which is why changing the narratives, changing the conversations, allowing people to think that difference is possible, seems to me a real act of activism. If you look forwards a bit, let’s assume your pilot project goes well, we can find funding for a national project. We’re five years down the line. Heaven knows what’s happened with the AI, but let’s not look at that at the moment. We’re on a trajectory we can still get our heads around. National conversations have been happening, gaining traction, giving people the space to understand that there is an alternative. Get out of the Thatcher ‘there is no alternative’ concept. Get to a point where we understand that the culture is collapsing, capitalism was not the only game in town and is failing, and there are other options. We haven’t necessarily nailed down what the other options are. It feels to me that that is a point where we accelerate the crumbling of the system. That we’re in a Ponzi scheme that is held together by a lot of people agreeing that this is the way the world is. At the point when a whole bunch of people agree that it’s not the way the world is, then we accelerate the collapse. First, does that make sense to you? And second, have you any felt sense of what emerges then? And this is possibly an impossible question. I’m just really curious to see where this goes.

Rowan: Yes, I think that agrees with my felt sense. It’s terrifying figuring out what does that look like? What does happen then? What happens in that phase of collapse? It could go in all sorts of very bad ways, given lots of the power structures that we have in our society at the moment. Given the role the media plays, given that there’s a lot of voices out there that are not going to try and push that sort of situation in a positive direction. So to me, I think making sure that as these conversations emerge, they’re hopefully driving towards less polarisation. I think that feels hugely important. And given what our government is continuing to try to do, to polarise conversations around climate and environment, trying to decrease polarisation conversations can help in that piece. One of the other pieces that we try to weave within the parents for Future community that would love to see happening at a much broader scale, is things like helping people to imagine and to envision the future that we want to go towards. I ran a session last week of helping people to come up with a collective vision, kind of drawing on some of Rob Hopkins work, of doing the time travel experience that he runs. Of getting people to sit in 2035 and experience what is that like? And then together to craft some sentences, to come up with a collective vision of this is what we’re going towards. And every time I’ve run those sorts of sessions, they’re really similar. And I think that’s really interesting, to be able to tell a story that whoever you run those sessions with, actually, we all want to get towards quite a similar future.

Manda: And how does that future look?

Rowan: Lots of the words that come through are around community and connection and thriving and nature and clean. You know, there’s lots of really positive ingredients in there, of people having time, of recognising that not being frightened about the future would actually free up a lot of headspace for people to be able to engage in a more positive way in their communities. And we’re not relying on fossil fuels. I haven’t begun to talk about the fossil fuel campaigning we work on, which is a whole nother strand of Parents for Futures work. But I think helping people to vision where we’re trying to get to would be hugely helpful. But the other piece think around what happens in that collapse scenario is how connected are we? Because if there’s stronger community connections, if there’s more trust between different people within communities, then potentially you’ve got a much more positive trajectory for what happens in those sorts of scenarios. Whereas if everybody is disconnected and not able to talk to each other, that’s when the worst scenarios are likely to play out. So the more we can do to build community and to build connection and trust and to imagine together where we’re trying to get to now, then whatever comes down the line, five, ten years time, it’s going to be more positive.

Manda: It feels like we just opened up a whole new podcast. One thing that came up for me there, was you said the role of the media in radicalising people to what we used to call the right and heaven knows what we call it now. And it occurred to me that people in the media are parents too. A lot of them. That if they were given options, their world might change also. Again, people are afraid because they’re looking at a brick wall and we’re driving very fast towards it. If someone were able to go, no, no, it’s okay. First of all, we know how to take our foot off the accelerator and second, let’s take the wall away. And let me show you a world beyond it that feels different. I think they would go for that, too. I hope they would. But you said we haven’t yet touched on what we’re doing around fossil fuels. Let’s touch on it. Tell us what you’re doing.

Rowan: So we’ve been doing a lot of work around lots of the offshore stopping new fossil fuel expansion. Campaigning work with the Stop Cambo coalition, with the Stop Rosebank Coalition. We’ve been doing that for several years to try and make sure that parents have ways to engage in the fossil fuel work. Trying to shift our energy systems away from fossil fuels feels hugely urgent and well, long overdue. So making sure that parents have ways to engage on those specific campaigns is part of our work. So how can we break down some of those campaigns into actions that feel really accessible for parents and that have got creative elements? How can we enable people to engage with MPs around some of these issues and provide them with enough support, so that they feel able to have that conversation and engage in other spaces also? So the fossil fuel campaigning piece has been a really important strand of Parents for Futures work, and we will continue to do really kind of visible or visual campaigning.

Rowan: So we try to bring creative elements to most of the campaigning work that we do, and that’s going to be something that we continue to work on. I think some of the next engagement work is likely to be actions that we’re planning just before COP in November this year. Which will be asking people across the country to to do some research and understand what their MP’s voting records are around specific issues, and then to highlight what those voting records look like, and to do that in a way that’s really joined up. With a moment to show this is actually what families are caring about, and this is what we’re trying to highlight politicians are saying. Which feels particularly urgent now that Rishi Sunak recently has been shifting some of his rhetoric and he’s trying to frame ‘this is what families want’ in a lot of the language that he’s using. And so that feels like something we need to counter and say, actually, not at all. What families want is that cleaner, thriving future for our children. Yes, we want a liveable planet for our children to grow old on, and we also want to be able to lower people’s bills in the short term, because a lot of families are struggling with the cost of living crisis and expanding new fossil fuel projects for fossil fuels that are going to be exported is not a way to lower bills.

Manda: No. So what comes up for me there is understanding from Simon Michaux that the materials flow is a real rate limiting step to a shift to a renewable future that powers us at the same level as the fossil fuels do. And I wonder, is there a strand of what you’re doing that is also helping people imagine a future that just doesn’t depend on cheap, abundant power? Or is that just too complicated and it’s easier just to stay with let’s just stop fossil fuels.

Rowan: So that’s a piece we would love to weave in more. And we’ve had some interesting conversations around that recently, that absolutely just shifting the current level of energy consumption from fossil fuels to renewables is not the solution. We need to shift our relationship with how we’re using the resources that we’re using. We haven’t found a really good way to weave that into our work yet, but I’m really open to ideas. So if if people listening have got suggestions around how we can more effectively weave some of that through, or bring some of our communities into some of those conversations around how we’re using resources, then absolutely. We’d love to talk more about that.

Manda: Yeah, because the transition town movement up to a point has been looking at that specifically for quite a long time. How do we de-power along with how do we de-grow in economic terms. You were talking about engaging with MPs. I am aware that there exist groups whose sole aim is to watch certain MPs, particularly the more spectacular ones from the Tory, you know, way out there, completely crazy wing. In our current political structure, however, MPs seem to be lobby fodder. They don’t appear to me to have much agency of any sort, and that heaven help us, five years down the line from now, I imagine we will have a different government, but I don’t imagine it will be behaving differently in any way. They’re still wholly owned by the lobby. That’s why they are where they are. Do you have a theory of change, and this is expecting a lot from a parents group, of shifting the nature of politics? It seems to me, like the media, politicians are parents too. Mostly, actually I think they’re grandparents a lot of them, some of them are parents to large numbers of children. And yes, they farm them all out to the kinds of schools where I’m guessing there are not many Parents for Futures groups, in the public schools of the UK. But that’s not to say they couldn’t be. Given that some ridiculously high number of our MPs come from the public schools, have you got any traction in there? And if so, can they evolve series of change that actually impact the MPs in ways that might see change within our existing system?

Rowan: An interesting question and a live one at the moment, as we’re thinking about our schools strategy, and trying to work out, do we go for a version of our work which is trying to encourage the people that we are engaging at the moment through our network in schools, across the country. And really in some quite diverse parts of the country, a range of areas, who are interested to start doing that organising within their own school community. And that has so far been growing quite organically. And there is some great work happening in Scotland. We’ve got a parents for Future Scotland group who are doing great engagement through schools in Glasgow specifically. But there’s another model which would be more intentionally identifying some specific schools where there are specific power structures, or where you can access power in a specific way, and try to engage through those schools communities. So there’s some open questions around our schools strategy. One of them is how do we best use the amount of time and resources and organising ability time that we’ve got, around schools, to have some impact. And could that be one way to do it? Maybe there’s some suggestions from partner organisations that that’s something that we should be considering, but it’s an open question at the moment as to whether we go down that route, or whether we take more of the building power in communities route, which is what we’ve been doing more of so far.

Rowan: So when we’re encouraging people to meet with MPs, that’s not necessarily expecting them to change their MPs mind in that meeting. That’s unlikely to happen. Mps have got a pretty strict book as to what they’re meant to say on various issues. But it’s more about empowering that group so that the group can start to feel their power, and they can start to have more of an ability and a sense of their own agency. And hopefully that’s where you can start to have some more impact. That said, we do get meetings with MPs regularly. We’ve had MPs saying no to Rosebank, that I think some of them have since changed their mind on, which is something we then need to go back and challenge them on. Last week we asked people to write to MPs after there were various announcements. Rishi Sunak’s announcements and then the announcement of the Rosebank oil field going ahead. And I think we had 450-500 people write to their MPs straight away, which immediately resulted in a number of MP meetings, including with conservative MPs who usually say no. So it’s interesting seeing that parents are able to get access in some spaces and I think that’s a particular way that we’ve engaged with some of our campaigning; has been using that coming in as parents. We’re just the Mums. Which gives you an ability to go into decision making spaces, even though I’m also a lawyer or somebody’s also a campaigner. But if you’re coming in there as a parent it gives you a different perspective to come into a decision making space.

Rowan: And we’ve used that in work with Lloyd’s of London, who are an insurance market. But we managed together with a partner organisation called Mothers Rise Up, to go and get meetings there with the chief exec of Lloyd’s of London. I’ve forgotten his job title. Bruce Carnegie-brown, who leads Lloyd’s. And we were there as parents having meetings with him, because we’d addressed him as a father. So, yes, recognising that people in decision making spaces are also parents and potentially they also want to be, as Roman Krznaric in his book talks about the good ancestor perspective. They also want to be well remembered. So if you can address them as parents with that legacy perspective and you go in there as parents to talk about that, sometimes that can be a way to open doors.

Manda: Fantastic. You’re actually creating the future we’d be proud to leave behind. Monumentally impressed. That sounds really interesting. And also it feels really aligned with what the Craftivist Collective does, where they’re let’s not go and assault these people, let’s find our common ground and embroider them a pillowcase, whatever. They’re so used to being assaulted that finding someone going, hey, you’re a parent too, we’re parents. You must have concerns for your children’s future in the way that we do. Can we come and talk to you about those concerns? Is a really different start to a conversation than everything you’re doing is wrong. Let us come and tell you how you’re doing it all wrong, which is never going to land with anybody. Yay! Well done. We’re running out of time astonishingly, I don’t know where the time goes. Is there anything else that we haven’t looked at yet that you’re doing that we really ought to know about?

Rowan: Probably lots. I mean, I haven’t talked about any of the global work, but maybe that’s another conversation for them.

Manda: Gosh, I think it would be. I really would like to have another conversation. When you’ve done your pilot and you’re heading towards the big one, I would love to. And so let’s park global stuff. For the people who are listening, who are global, less than half are in the UK and the rest are all spread around the world. What can people who are listening do, whether they are parents or not, to support you?

Rowan: So I’d say have a look at the parents for future UK’s website. There’s ways there that you can join, if people are interested to join parents for future. We have regular joining calls, which are a very welcoming space held by a lovely team of people. And yes, come and get involved and be part of it. But also, if you want to join, we have a mailing list, we have newsletters that go out regularly, and there’s a specific mailing list around the conversation’s work, because I think we’re going to have specific interests around conversations rather than around all of the rest of the work. So if you want to sign up just for that, then you’ll get updates on the conversations project as that grows. And then otherwise, we’ve got a very active social media team. Brilliant team of volunteers on social media, so please support them. There’s a lot of content that goes up there as well.

Manda: Fantastic. Okay, I will put all of those links in the show notes. So people head off to the show notes and you can click on the links. Get involved because this feels you’re right at the leading edge of emergent processes. We have no idea where they’re going to go, but you’re giving it good heart, good connection, good connection to the web of life, good connection to our children’s futures, everything that we would want to be out there in the world, you are doing. So Rowan, thank you so much for helping to found Parents for Future and then for coming on to Accidental Gods.

Rowan: You’re very welcome. It’s been a pleasure to talk to you.

Manda: Thank you. And that’s it for this week. Enormous thanks to Rowan and all of the others in Parents for Future, who are having so many conversations across such a wide range of issues at such depth. This is the kind of work that we all could be engaged in. Finding out how to have the emotionally literate conversations. How to approach people, how to talk in ways that create community rather than splitting it apart. All the way through this podcast, when we get to the question of what can we do? Our guests so often say we need to build community. And then we get somewhat stuck. Because that’s really easy to say and really hard to do in our fragmented, individualised world where we are so encouraged to enter our own silos and not step out of them. And now Parents for Future are offering a forum to anybody (I really do want to stress that – not just for parents) who wants to engage in broader conversations, who wants to get together with other people who get it and find out what we can do. Because we are stronger together. And one thing Rowan said at the end after we stopped recording was that there’s a podcast called The Week, which is at the website theweek.000, which yes, appears to be a URL suffix.

Manda: Who knew? But what they’re offering is something similar to parents for future that you can do now, before the Courageous Conversations pilot is over. They offer facilitation of a group experience where you get together with friends or family, or a group of colleagues, and you gather three times during a week, hence the week, and you watch together a one hour documentary about the climate and ecological crisis, and then have a guided conversation for the next 30 minutes or more if you want it, to help you make sense of it all. So I’ve put a link to that in the show notes as well. If you want to crack on and start holding conversations now, then that is one option. And after we finished talking, Rowan and I booked in again for another conversation next March, which will go out in early April, where we will be able to look at the results of their pilot project, explore more about the Parents for Future spread globally, and look at how we can begin to have courageous conversations with whatever they are able to spread out around the UK and the rest of the world.

Manda: So I look forward to that next spring. Closer to that time, we will of course be having another conversation next week. In the meantime, thanks as ever to Caro C for the music at Head and Foot. To Caro and Alan Lowles of Airtight Studios for the production of the podcasts. To Anne Thomas for the transcripts. To Faith Tilleray for the website and managing the Instagram and the YouTube channel. And every bit as importantly, for those long walks and conversations at the dinner table, around the fire and everywhere else, on where we’re going and how we can move forward. And last but never least, enormous thanks to you for being part of those conversations. For turning up to listen and engaging with all that you bring in the ways that we can create that future that we would be proud to leave behind. And if you know anybody else that cares about that and wants to know more about how we can begin to hold these conversations, then please share the link to the podcast and then send them off to Parents for Future. And that’s it for now. See you next week. Thank you and goodbye.

You may also like these recent podcasts

ReWilding our Water: From Rain to River to Sewer and back with Tim Smedley, author of The Last Drop

How close are we to the edge of Zero Day when no water comes out of the taps? Scarily close. But Tim Smedley has a whole host of ways we can restore our water cycles.

This is how we build the future: Teaching Regenerative Economics at all levels with Jennifer Brandsberg-Engelmann

How do we let go of the sense of scarcity, separation and powerlessness that defines the ways we live, care and do business together? How can we best equip our young people for the world that is coming – which is so, so different from the future we grew up believing was possible?

Brilliant Minds: BONUS podcast with Kate Raworth, Indy Johar & James Lock at the Festival of Debate

We are honoured to bring to Accidental Gods, a recording of three of our generation’s leading thinkers in conversation at the Festival of Debate in Sheffield, hosted by Opus.

This is an unflinching conversation, but it’s absolutely at the cutting edge of imagineering: this lays out where we’re at and what we need to do, but it also gives us roadmaps to get there: It’s genuinely Thrutopian, not only in the ideas as laid out, but the emotional literacy of the approach to the wicked problems of our time.

Now we have to make it happen.

Farm as Church, Land as Lover: Community. farming and food with Abel Pearson of Glasbren

The only way through the crises we’re facing is to rekindle a deep, abiding respect for ourselves, each other and the living web of life. So how do we make this happen?

STAY IN TOUCH

For a regular supply of ideas about humanity's next evolutionary step, insights into the thinking behind some of the podcasts, early updates on the guests we'll be having on the show - AND a free Water visualisation that will guide you through a deep immersion in water connection...sign up here.

(NB: This is a free newsletter - it's not joining up to the Membership! That's a nice, subtle pink button on the 'Join Us' page...)