#229 How do we live, when underneath the surface of everything is an ocean of tears? With Douglas Rushkoff of Team Human

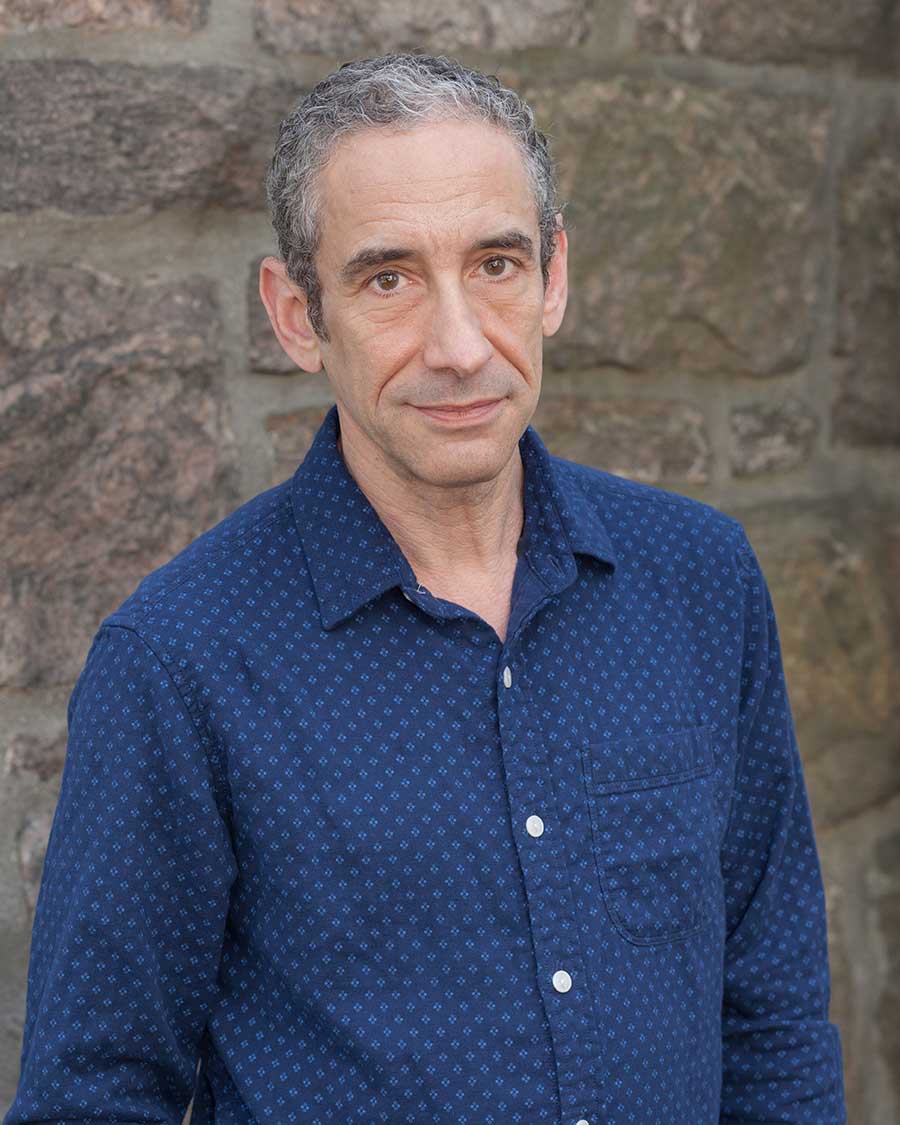

Our guest this week is Douglas Rushkoff, a man whose insights and intellect have earned him a place among the world’s ten most influential intellectuals by MIT. As the host of the acclaimed Team Human podcast and author of numerous groundbreaking books, including “Survival of the Richest,” Rushkoff’s work delves into the intricate dance between technology, narrative, money, power, and human connection.

Douglas shares with us the palpable “ocean of tears” lurking beneath the surface of our collective consciousness—a reservoir of compassion waiting to be acknowledged and embraced. His candid reflections on the human condition, amidst the cacophony of a world in crisis, remind us of the importance of bearing witness to the pains and joys that surround us. He challenges us to consider the role of technology and AI not as tools for capitalist exploitation but as potential pathways to a more humane and interconnected existence.

As we navigate the complex interplay of digital landscapes and social constructs, Rushkoff invites us to question the gods of our modern age—wealth, power, control—and to seek solace in the simpler, more profound aspects of life: friendship, community, and the transformative power of awe. His vision for a society that embraces these values, even as it stands on the precipice of uncertainty, offers a beacon of hope for those willing to engage with the deeper currents of change.

For listeners yearning to dive into the depths of our potential for transformation, this conversation with Douglas Rushkoff is an invitation to join a chorus of voices seeking to reshape our collective destiny. Tune in to this episode of Accidental Gods and join us on a journey to redefine what it means to be human in a world teetering between collapse and rebirth.

In Conversation

Manda: Hey people, welcome to Accidental Gods. To the podcast where we believe that another world is still possible and that if we all work together, there is time to create a future that we would be proud to leave to the generations that come after us. I’m Manda Scott, your guide and fellow traveller on this journey into possibility. And part of the wonder of this is that we’re able to speak with others who are way ahead of us, or at least of me, on the path towards that more beautiful future that our hearts know is possible. And on this front, our guest this week really doesn’t need any introduction. But for those of you who are new here, I would say that MIT named Douglas Rushkoff as one of the world’s ten most influential intellectuals, which is pretty cool, right? He’s the host of the absolutely outstanding Team Human podcast. He’s the author of 20 books, the most recent of which, Survival of the Richest; Escape Fantasies of Tech Billionaires, is referenced quite often on this podcast. Just before that, he released Team Human, which is obviously based on his podcast, but the ones you will have heard of and most likely read are the bestsellers Present Shock or Throwing Rocks at the Google Bus or Be Programmed, or Life Inc. or Media Virus.

Manda: You might also have seen his PBS frontline documentaries ‘Generation Like’, ‘The Persuaders’ and ‘Merchants of Cool’. His book ‘Coercion’ won the Marshall McLuhan Award, and the Media Ecology Association honoured him with the first Neil Postman Award for career achievement in Public Intellectual Activity. At a more local level he is the progenitor of the word screenagers, which I turned into a hashtag in the book that will be out quite soon. And he coined other concepts like viral media and social currency. So all in all, his work explores how different technological environments change our relationship to narrative, to money, to power, and to one another. He has said, if you don’t know how the system you are using works, the chances are the system is using you. He is an absolute titan of our arm of the intellectual ecosystem, and it was a real honour to explore what he’s thinking and feeling and imagining now, as our world spins ever faster on the road to a barely imaginable future. So people of the podcast, please do welcome Douglas Rushkoff of Team Human and so much else.

Manda: Douglas. Welcome to the Accidental Gods podcast. It is a delight and an honour to have you here. How are you and where are you this delightful February day? Whatever time it is in your time zone.

Douglas: I’m fine. Fine enough. I’m in Hastings on Hudson, New York. A town named for some kind of English town, I’m sure.

Manda: Yeah. Well, there was a minor historical event at one point a while ago.

Douglas: Yeah. So I’m about half an hour north of New York City, and it’s, when is it? Around noon my time.

Manda: Yay! Very good. I was speaking to someone in Columbia earlier in the week, and I apparently got her out of bed at 5:00 in the morning, which was completely not part of my plan. I don’t do mornings, she doesn’t do mornings. She was very kind to me. Super. So in all of the length and breadth and depth of all of the things that you think about, what is most alive for you at this moment? Because there’s so much that we could talk about, but I would really like to just what is it that’s sparkling at the top of your amazing and extraordinary mind today?

Douglas: What’s interesting, I mean, what’s sparkling in my amazing mind and what’s most alive for me are maybe two different things. To the first question, what’s been most alive for me very lately, and I’m not yet sure how to how to deal with it, is the sense that just under the surface of everything is an ocean of tears.

Manda: Yeah.

Douglas: I kind of got it in my last little shamanic adventure. But the more I think about it, the more I feel like I stay in motion and I stay distracted and doing things because I’m afraid if I stop, I will start to cry and never stop. And I feel like what it really is, is it’s really more the ground is compassion. The tears are just cleansing the crying is not even the thing. That what’s beneath that is the compulsion, the demand to experience compassion for everything that’s happening all around us, all the time. To just bear witness and be present and metabolise all that’s going on. The human condition, I’m sure there’s many other conditions, but the human condition right now just is so heartbreaking to me. It’s so heartbreaking how much that’s happening. And I realise that the kinds of actions I do to alleviate pain or horror or confusion are really minimal compared to the task at hand. That it starts to feel to me like not to be completely passive, but that the most I can do, the best I can do is somehow serve as some kind of a doula, you know? Is to bear witness, to be present, to acknowledge, to validate and just and that that matters more. But what’s most alive for me is a fear in some ways, is this sense of tears, a sense of sadness and slowly, almost like titrating my ability to be there and experience that and not get just swept away or overwhelmed into some despair or depression.

Manda: Right. And I am fairly certain that that will be shared by everybody who is hearing this. And I’m wondering, because we’re recording this at the end of the week where Alexander Navalny was murdered earlier this week, the chaos in Israel and Palestine is showing no signs of getting any less, we’re witnessing things on our television screens that I certainly never thought I would see in the 21st century. And I am peripherally aware that such things were happening in Yemen, in other parts of the world, and that they’ve been going on for all of my lifetime and before. The annihilation of colonialism on all of the colonised nations has been barbaric and horrible for the whole of our recent history. And if we go back far enough, you know, the Romans invaded and colonised Britain 2000 years ago, and it was grim. And prior to that, bad things were happening. I don’t know if you’re familiar with Francis Weller’s concept of initiation culture versus trauma culture, listeners to the podcast will probably be getting slightly bored of me mentioning it, because it’s my most recent light bulb of that schism, that original trauma that we’ve been carrying down the line for 10,000 years probably some of us, and then inflicting on the rest of the world. And yet it feels as if the horror is greater now, or it feels that to me, and I wonder if it’s because of what we’re seeing or because we’re becoming aware that we’re in the middle of the sixth mass extinction, which no previous human has lived through a mass extinction, that humans didn’t exist when the last mass extinction was happening. Have you a sense of, first of all, what is it that’s bubbling to push the grief to the point where we feel it to this extent? And also whether you think this is, or whether you feel that this is a universal sense, certainly where you are?

Douglas: Well, part of what makes it worse, if you will, is the fact that our nervous systems have been extended through all of the media that we use. So I don’t want to say that we’re aware of what’s happening everywhere in some fundamental way, but we are certainly receiving the data points from everywhere. And we’re receiving all the data points in relatively one way media. So we can feel all the pinpricks of every trauma that’s happening all around the world, we’re connected to it, but not in a way where if it’s happening locally, that you can run over and pick the baby up that’s crying. You know, we can’t do that. We can’t reach through our screens or our twitters or whatever. All we can do is comment on the thing, and that’s an unsatisfying action. I’m going to put my thumb up or do a heart or do a thing, it doesn’t.

Manda: Or a cry emoji. It really doesn’t touch it, does it?

Douglas: It doesn’t. And it doesn’t help who’s on the other end. So we’re all overwhelmed with the sense of powerlessness as we’re, with our bodies and nervous systems witnessing so much more pain and trauma and chaos, but not in in contexts where we feel like we can do anything quite about it. So that’s part of it. Part of it is the scale on which the destruction and torture and genocide and all are happening is industrial scale. I mean, and that’s kind of since World War One, when we started to use mustard gas and machine guns and artillery. You know, that’s when we applied the industrial age technology to mass murder and to military. So that was shocking to the nervous system, in the same way that when you see footage of a drone blowing up a building. So there’s bad guys in the basement, but then all these good people in the floors on top getting annihilated. You see it on CNN, but you feel it, you know what’s going on. So there’s that. Those two things, the increased surface area of our nervous system, of our sensory apparatus, combined with the exponential scale on which destruction is taking place, and then the layers of confusion and kind of collective trauma. I mean, put them in any order you like:

Douglas: Digital technology, Donald Trump, American imperialism, disinformation, Covid, the Middle East conflict, the layer upon layer of things that we don’t have the cognitive or emotional or social apparatus to process, to metabolise, all combine. Plus we all, all the time, had some individual denial of death, Becker, you know, kind of thing going on. And now we have it on a collective scale. That any rational person understands that, let’s be optimistic, there’s a significant possibility that at least the human race and a majority of other species are being wiped out, unnecessarily really, enthralled to capitalism. And that’s disturbing. People understand that. Even kids get it, even if we’re not talking about it in front of them. They know they’re walking around with adults who think the whole thing is going to shit. It all comes together. But the ocean of tears, which is the metaphor I’m stuck with right now, The Ocean of Tears was here before all that. When I started thinking about the Ocean of Tears, I look at Bible characters. They’re aware of it, you know. There’s a great scene in what is it, judges? Where Samuel goes to God and weeps and apologises that the people want a king. They’re not satisfied with the with the priest and with God, they want a king. And Samuel goes to God and apologises. I’m sorry. I’m so sorry. And to me that’s heartbreaking, because he’s looking and saying, we’re here in this sacred, beautiful, holy planet together and, uh, they want a king just like everybody else. They want politics and power. And God’s so sweet with them, he’s like, Samuel, just don’t sweat it. It’s okay. Just meet the people where they’re at. It’s okay, give them a king. And if you look at sort of the footnotes of the Bible, God says just pick the tallest guy, just pick the tallest guy, put a crown on him. As if to say it so doesn’t matter who’s the king, just give them a freaking king and hope that they develop past that.

Manda: Oh, this is so interesting. Okay. Are you familiar with the Dawn of Everything by David Graeber and David Wengrow?

Douglas: Yeah.

Manda: So I’m thinking, so they pick the tallest guy they want a king is integral to our trauma culture. So let’s take a step back. I hear all that you’re saying; the ocean of tears is a thing. I don’t think there’s a single human being on the planet who thinks the existing system is working. Where we disagree is how we fix it. Where we might find agreement, I would say, is if we all got together and worked out what our values were, we’d find actually we had quite a lot of common values. And exactly what you’re saying is that sense of needing agency, the whole Rebecca Solnit Paradise Made in Hell required that people had agency. And what we’re seeing at the moment, what we’re having with exactly as you said, our extended nervous system in this hyper complex, super connected world that we’ve suddenly created, in evolutionary terms it’s less than the blink of an eye of going from chipping stuff on rocks and leaving them for people to find as a message to being able to talk to each other on other side of the planet in real time. And we still have our Palaeolithic emotions and our medieval institutions, and we’re not quite equipped for the hyper complexity of this.

Manda: So here’s a question. Let me frame this right. In my reality and my time frames; I live in the wildlands of Britain, and my historical time frame sinks back into pre-Roman times quite fast. Everything between here and there is just noise really, and I think that we were connected then. That we wouldn’t have wanted a king, in the way Graeber and Wengrow described that the Inuit had 5000 years of social technologies designed to make sure that nobody was a king, that nobody had that kind of power and that nobody wanted it, and that if somebody stood up and went, hey, guys, I’m the king, they would have been laughed at to the point where they’d just give that up as a bad idea. And that my big question for myself now, and I’m asking you now, as one of the brightest people I can imagine ever meeting, how do we get from this trauma culture that lauds and elevates the kleptomaniac sociopaths?

Because we haven’t got the social technologies to tell them that being a king is not what we want. To tell ourselves that what we want is not a strong man, we want a strong community instead. How do we build forward from that into a new kind of whatever we want to call it; Weller calls it an initiation culture, I would perhaps call them Disconnected and Connected rather than Trauma and Initiation. But the concept is the same. We can’t go back. Nobody wants to go back to living in caves and anyway, we don’t have the life skills to be forager hunters, and there are too many of us. How do we build forward to a place where we feel heart connected to the whole of the web of life? Because I think then the Ocean of Tears becomes an Ocean of Connecting and Communicating. And we ask of the web of life, what do you want of me? And it says, we need you to do this, and this is something that only I can do or the web would have asked somebody else. And I get on and do it and I’ve found a place in the world. How does that sit with you? And have you got the jump cut of here to there? Is the bit that I am missing, of how do we get from where we are to where we need to be. Over to you.

Douglas: Well, I do feel like there’s a reasonable chance that our future might look like a small subset of us living, foraging and doing, you know, small scale permaculture. If we end up with hundreds of millions rather than billions of people on the planet, you know, 80-90% population drop thanks to some ridiculous virus or genetic construction or pollution or, or.

Manda: Somebody presses the big red button.

Douglas: You know, or even a lot of little red buttons even. They just keep pressing the little red ones they’re pressing. That happens anyway and even that, the transition is bad, but even that is not as bad as all that. Sometimes I think that my writing and things that I’m doing are really documents intended for the desert. You know, the people between Egypt and Canaan, you know that those generations after they’ve escaped the bondage of Western capitalism or whatever we’re living in. But I mean, the real question you’re asking really is almost a theory of change type question. How do we get from here to somewhere better? And for me, it’s divorcing our theory of change from the almost quasi eugenics informed kind of techno solutionist framework of how do we get people to….blank? You know, a lot of times I’ll do a talk with great social justice, wonderful progressive people. All right okay Doug, but just how do we get people to, you know, be nice? How do we get people to use this? How do we get people to stop this? And once you’re in the framework of ‘how do we get people to’ we’re already off to the wrong start, because now we’re trying to assert our judgement on them. How do you get them to do this? Oh, well, I’m a smart tech bro, and I know if I could just get everyone to drive electric vehicles, then the world will be fine. And it’s like, dude, where are they getting the rare earth metals for those electric vehicles? Where are the children being sent into the mines and why vehicles? Where are we going? Why are we going to so many? It’s like no one knows better. So for me, and I’ve kind of looked back and developed my theory of change in the rear view mirror, by looking at what have I been most satisfied with in terms of my work. Over time, what has informed me? And I found really my theory of change breaks down to four main activities that I’ve been involved with.

Douglas: So the first one is to denaturalise power. And all I mean by that is help people distinguish between that which are sort of given circumstances and what are the social constructions of our society. So it’s as simple as saying, well, that stuff in your purse, what is that?. And they say, well this is money. And I say, well that’s not money, that’s paper that we’ve assigned money value to. Being able to really distinguish between something like capitalism, which we accept as atmosphere: that’s the way business is done. And you say, well, there’s other ways of doing business; you look at a David Graeber book. And ‘oh, well, you know, democracy is the most advanced form of government because it’s come through these stages from ancient Greece’. Well, there are a lot of other forms of government that have been through all different; this is one way that we’ve decided to do things and we could choose other ones. So that’s sort of the first one. It’s a denaturalise power to help us see that these things are not nature, that they are constructions, they’re inventions.

Douglas: And then once we’ve done that, then what I’ve been trying to do is trigger agency. Which is to trigger people’s thoughts that, well, if this money is just one kind of money, how might I make money differently? How could we do this differently? So there’s a public school and you go through 12, and what else is there? Oh, school is here to train you for jobs. Oh well what else might it be for? What is it for in other places? What did it start out for? To actually then think so now I can rewrite the code. I can create new institutions. I can revise institutions. It’s like Talmud and the Constitution of the US, that we are invited to adapt and modify and recreate. And once you’re doing that, you get to the third one of mine, which is to resocialise people. That you don’t do that alone, you do it together. So I’m trying to either resocialise people or if I want to get lefty about it or Marxist, resocialise ‘the people’. How do I help? And that was my whole team human project. How do I help people understand that being human is a team sport? That you can’t do it alone, that once you establish a rapport and develop solidarity, then you can actually rewrite the codes. Agency is not something you experience alone. And then finally, in order to do that, I’m trying to cultivate awe and that’s the weirdest, most psychedelic artsy one. The experience of awe is really just the experience of connection with everything that’s around you. You know, if you have a great rave or a psychedelic trip or an experience of nature, you experience yourself as part of this larger framework. And once you do that, you’re more social, you’re more generous, your immune system gets better. You know, after an experience of awe, you no longer think in that libertarian, individualistic, every man for himself way. All your oxytocin and other things.

Douglas: Awe is really I would think, and this is the booby prize in some ways, but awe is a gateway to compassion. Awe is the gateway to realising the presence of this ocean of tears and then understanding, oh, but these tears are the water. That’s the connection, that’s the compassion, that’s like the Pisces. You know, all the water signs that that well up and feel the thing, that’s the intimacy that connects us all that is only bearable if you’re acting in a way that’s not hurting others. You can’t bear the connection with others if you’re imprint on this world is negative, is selfish, is extractive. So I sort of think of these things in that order: wake people up to the fact that the things they’re mistaking for nature are actually social constructions. And then say, oh, now you’ve got the agency to make your own stuff, and oh, wouldn’t it be more fun to make your own stuff with other people? And the way you’re going to connect to other people is through the experience of awe, so you’re less afraid to do that. So that’s sort of my theory of change. There’s no agenda in it. It’s more about engendering the conditions for a more positive, social, political, economic landscape.

Manda: Brilliant. So I have a whole list of things firing off that I could ask. Before we get to them, in a recent podcast that I listened to, which could have been recorded years ago, I can’t remember, there were so many that I listened to in the last couple of days. You described a psilocybin experience that you had in which you experienced the mycelial connections with the therapists that were with you. Is that something you’d be happy to talk about here? Because that seems an actual lived experience of what you have just been talking about.

Douglas: I know, and I believe in in magick, you know, magic with a K in terms of directing one’s will and having sigils and things like that. But I haven’t had that many direct experiences of what might be considered supernatural or, you know, clairvoyance or sixth sense kinds of things. This was a kind of psychedelic therapy that I advocate, i guess, if I’m supposed to advocate something, if I’m expert and I advocate. The kind I like is where you have a therapist of your own that you go to, that’s your therapist. And then if you want to do a psychedelic session, you go to people who are adept and experienced at facilitating a psychedelic experience, which is not therapy, right? It’s basically people who can hold space, who are great at holding space, who are more like a doula than a doctor. They’re there and they’re present, so if you’re freaking out they know how to help you process it. But their real function and I didn’t realise this, I thought they were going to be there with little books, they’ll journal, they’ll talk to me. I didn’t know what what it would be. But you know, in the opening of my session, they said a lot of times people want to talk. And if you want to talk, we’re here to journal the thing for you, but we’ve found it’s usually best if you just stay with yourself. Just be there and we’re here for you. It’s not like you’re not allowed to talk, but, you know.

Manda: You don’t need to talk.

Douglas: So I’m an experienced psychedelics user. I mean, I’ve done heroic doses. Usually I’ll do a heroic dose with an intellectual friend and walk around and we’ll talk the whole time, you know, about the nature of the universe and politics and Trump. But I was like, oh, all right. So I just kind of laid down in Shavasana for six hours; fine, I’m not going to talk. I’ll do this. And the interesting thing was as the mushrooms came on, the psilocybin it was Golden Teachers which are a particularly compassionate species. There’s more confrontational ones, you know, whatever they call like penis envy and some other ones. But Golden Teachers are gentle with you, and gentle is fine.

Manda: It’s still profound.

Douglas: Yeah. Gentle is the whole. I mean, does anyone know how to make love anymore? Right. Gentle. It’s the lightest of touch. The lightest is everything, so I’m fine with that, I don’t need a confrontational mushroom. But anyway, so they’re going in and doing their mycelial thing and I became aware of the two women who were in the room and the mycelium kind of made me feel as if my nervous system were extending and reaching up into theirs. It was so intimate. I mean as or more intimate than the most intimate sex I’ve ever had. And I’m feeling, ‘Oh, yeah you had Covid. Wow.’ And oh I was feeling that and one and ‘Oh, you’re here; you know, you really are about, your essence is really to metabolise other people’s trauma, that’s what you do. That’s why you came.’ And I’m feeling up in there and then I’m like, oh, right, there’s this other one, and I went up into her and I was like, ‘Oh, you’re like a six year old from another planet who came here just to play with us’. And then I had the whole the session and all. But afterwards I told them and when I said about the six year old from another planet, both their jaws dropped and they said, you know, when she meets people she describes herself as a six year old from another planet who came here to play with us.

Douglas: It was not like that great Long Island mystic, a reality show here, there’s a Long Island mystic who sees dead people. It’s not like, oh, great, it’s proof of something, but it’s very validating. To have them say that what was happening was real. And what was happening for me in that experience was no profounder for me than it was for them there. And I thought a lot about the profound mitzvah, this blessing I’ve had of being with a handful of different people as they’ve died. And I’ve looked at it at the beginning as, oh my God, I’m the one here. I’m the one in the hospital next to this bed. Everyone else is gone. But that transformed in those moments, even with them, to realise, oh my gosh, I’m here. I knew on a different level they knew I was there, that I was present and metabolising their passage, witnessing their passage, holding their hand as they walked through the portal. I mean, what more profound experience of life can you have than to be with someone else, to be honoured by circumstance, to have been the one that was there when they passed over. I mean, that’s, uh! And that’s what I realised, what they were doing for me. I mean, I felt initially selfish; I’m lying here for six hours having my trip, and they’re just sitting there. But no, they’re sitting there. And then I realised, and that was when I got to the sort of Ocean of Tears type stuff, of that’s the best we can really do for each other, is be there just with each other, see each other. And then if, as I’ve been accused, someone once accused me of, oh, you’re just, uh, you’re just in the band on the deck of the Titanic playing music as the ship goes down. You know that I’m doing my Team Human and my talking about meaning and all, but the planet is dying. I’m like, what’s wrong with being in the band on the deck of the Titanic as it goes down? You were born to be a musician. You play the trumpet, that’s what you do. And now when the humans in your midst are in their most in the greatest peril, when it’s all going to shit, you can play music.

Manda: You can make the world beautiful as it goes down. And create the awe that you’re talking about.

Douglas: And so it’s all okay.

Manda: Yeah. It would be good if we could steer the ship away from the iceberg.

Douglas: Yeah.

Manda: But let’s talk a little bit, if we can go deeper into this because this feels a tremendous synchronicity. Yesterday I was talking to someone in the middle of the Colombian jungle. An amazing woman called Drea Burbank, who works with Colombian indigenous elders endeavouring to funnel money their way. Basically, that’s the shorthand of what she does. And they’re also bringing a legislation to the UN to try and create a legal rights of nature, which would be amazing. I mean, given that human rights are currently being trashed all around the planet and the legal rights seem not to matter, I could get a bit sceptical, but if we had legal rights of nature enshrined in UN law, it wouldn’t be a bad thing. And so she used to be a human doctor and she describes the Yahi, the ayahuasca elders, the people who’ve been through the full Colombian training, as being the equivalent of top level surgical consultants of energy. And one of the things she explicitly said was 80% of the time, it’s fine. It’s like, you know, any registrar can do basic thyroidectomies, but if something goes wrong, that’s when you need the person who knows what’s happening because they can fix it, and that these guys are the equivalent in that if something goes wrong in this whole group of people where you’re playing multidimensional chess with the energetics of all of them reaching out and joining the mycelial network, then they can walk and navigate the pathways of the mycelium and make sure everybody comes back in a state where they feel intact enough, intact.

Manda: And I listened to that and I’m completely on board with believing that she’s right. And my question then for her, and for you now, is whether Western people like the people who sat with you, can evolve do you think that level of energetic precision and awareness and skill? I still am striving for a point where individuals can have extraordinary experiences using plant teachers, or any of the other ways that the human mind can extend out. And there are 8 billion of us on the planet and a few thousand, even a few tens of thousand, even possibly hundreds of thousands of us, it would be good if there were millions, if not billions. And we would need then that many people with that skill. Because you’re very switched on and very experienced and it all went right from the sound of things. We need the people who can fix it on the 20% of the time when it goes wrong. Have you encountered in your exploring Western people who could hold that strongly? Does that make sense as a question?

Douglas: Yeah. But I’ll initially answer it in a different way.

Manda: Okay.

Douglas: Before I did this assisted psychedelic therapy session, I was originally supposed to go to Costa Rica with a group of a psychedelic coach and therapist in training. And I’ve occasionally spoken to groups. I mean, I’m not a psychedelic trainer, but I know different things. And sometimes the training courses like to have me as someone to talk about Team Human and the human Agenda and some of that sort of stuff. Sort of more context creation for the work than explicit instruction on how to deal with Yahi or something. And I was going to go and then it became clear to me that the facilitators of this gathering were in over their heads. They had people with PTSD who were in the group, they weren’t ready to be leading something like this, even with mushrooms or ecstasy or whatever. This work has to be done in a particularly responsible way, particularly with Westerners. And so I decided I wasn’t going to go there. And then I do have I mean, because I’m connected, I have friends who are doing the best of the best retreats in Costa Rica, and I get invited at cost, you know, because I’ve written books or whatever. And I’m loved by some people, so it’s nice. And so I had a choice. I was like, oh, so I can go down to Costa Rica for five days and do it with a super shaman dude, right. Rainforest experienced whatever. Or I can drive eight miles from here, and do it with two women who were raised five miles from where I was raised.

Manda: Okay. This is community.

Douglas: And I started to feel, well, you know, I’m not a psychedelic tourist. Nothing against people who go down there and do those things. But it’s like, that’s not where I’m from. That’s not my ground. That’s not my jungle, that’s not my place. And I’m doing psychedelics as a suburban, north-eastern intellectual, American Jew. I’m not indigenous, I’m native to here. This is where I am. And suddenly it felt way more appropriate for me to do it right here with people who are from my context and in my thing. So I don’t know if we need lots of people who are capable of doing group shamanic ritual work with Westerners, because we’re not a group shamanic. That’s not our tradition. That’s not our thing.

Manda: It is if you go back far enough. You know, 300,000 years of human evolution, 99% of it was group shamanic work. There must be a little bit of us in there that comes out of the womb expecting that.

Douglas: I’m sure there is. But that’s a heavy, it’s a tall order. Right now it’s a tall order for us. If we’re looking at triage for a civilisation that’s about to go off an existential cliff.

Manda: Okay.

Douglas: I don’t know that we need that, I think we need we need people who are experienced with neurosis and personality disorder and the western, things, our personalities. And I don’t know that most people’s first first decade of experience with these chemicals and plants needs to be that. If I could just get people into a freaking drum circle or a sound bath or a group meditation, you know, that’s already for these people…

Manda: It’s a big step.

Douglas: It’s huge. Right?

Manda: No. That’s interesting. It’s a very valid viewpoint.

Douglas: I mean I’m more than willing to play there, to go in with a dozen people and lie on the ground outside in the clearing in the rainforest with a shaman. But it feels to me like that doesn’t really scale. I don’t like spending the jet fuel. I look at all the tourist spots, I get all these emails, you know, oh we’re doing a retreat for leaders in Honduras. Like, leaders? That’s a great setting to go into a psychedelic trip: I’m a world leader, so it’s important that I have a psychedelic experience

Manda: Yeah and I’ve spent a ton of carbon to get there and another ton to get home. And then I’m going to talk to people about the climate emergency.

Douglas: And it’s all so close to home. I’m a big advocate of demonstrating to people how accessible these states are. The first book I ever wrote, it was in the in the 80s, it was called Free Rides; Ways to Get High Without Drugs. And the idea at the time was, I thought that the reason these drugs are illegal is not because there’s something wrong with the drug; the drugs are illegal because of the states of consciousness they offer are destabilising to work a day reality.

Manda: Absolutely. They’re destabilising to the death cult of predatory capitalism, for sure.

Douglas: Exactly.

Manda: Particularly during the Vietnam War, you know, if you’re all sitting there going peace and light and love, man. And no, I don’t want to sign up to your nasty little war, thank you, that’s extremely destabilising to the people who would like you to go and be cannon fodder. Okay, this is making a lot of sense, and I think you’re right. And I’m remembering, this is an aside, but I think it’s interesting in the conversation. I don’t know if you’re familiar with Elliot Cowan, who wrote the book Plant Spirit Medicine? He died recently, a very interesting gentleman and plant spirit medicine is fascinating. And he trained with a Huichol medicine healer called Don Lupe and he tells the story of bringing Don Lupe to Los Angeles. When Elliot was a little lad, because he was American but he trained for acupuncture in Britain and came back to the States, I think. He used to watch Star Trek, and he used to imagine leading the aliens and showing them around his world. And he said, Don Lupe was just like that. When he put him in the hotel room, the light was on, and when he got back the next morning, the light was still on because Don Lupe didn’t know what a light switch was and he didn’t know how it switched off.

Manda: And then he takes him out around Los Angeles. And at that point, Elliot was Don Lupe’s senior apprentice, because all the young Huichol all wanted to go off and be doctors and engineers and lawyers, and there’s this white man who wants to train. So Don Lupe is training him up, and he would boast a little in the evenings and he’d say, you know, there is nothing that I can’t heal. I can heal anything. And then he took Don Lupe around Los Angeles and after half an hour Don Lupe is saying, you have to take me home. All of these people are beyond my healing, I could not heal any one of them. And while you were talking, I was thinking we need the people like the two ladies who held you. Or three. You were definitely talking of three there. Or just two, but three different realisations. Because they could potentially be able to help the healing happen.

Douglas: Right. Exactly.

Manda: In a way that somebody from the Huichol or the middle of the Colombian forest, they can deal with gangrene and snake bites, but they’re not going to be able to deal with the destroyed mitochondria from three generations eating ultra-processed foods. It’s not within their general perception, I think.

Douglas: Right. And it doesn’t mean we’re hopeless. Just because Thor, you know, or Odin couldn’t heal the leper in the Middle East, doesn’t mean he can’t heal the Vikings. Right?

Manda: Right. Yes.

Douglas: And the leper in the Middle East, they’ve got Jesus. It’s like it’s all good, you know? And that’s the thing. I always understood charity is close to home very differently. That it’s not like charity, that you give to people around you. It’s like you get your charity from close to home. It’s a very New York New Age thing where people travel all over the place to find their guru, and they won’t accept that the guy at the counter of the bodega where they buy their morning coffee, that is your Buddha. He’s there. The universe has brought him to you. Listen to what he’s saying. He doesn’t have to know he’s the Buddha. But he’s saying it. He’s acting it. He’s being it, you know. They’re all the Buddha. And it just makes life so much easier. Then there’s no search, there’s just open openness.

Manda: And listen and feel and feel the ocean of tears and swim in it and see where it takes you. And I’m wondering where we could go from here. I’m thinking there’s a lot we could go down this avenue further, but we’ve probably got about 15 minutes and I had an idea that we could talk about tech and AI and where that might take us also, but that’s going to take us into a very different headspace. Where would you actually like to go, Douglas?

Douglas: We can talk about tech. I mean, the natural place my mind was going as we were talking was I feel like the ocean of tears I’m talking about, that this realm of compassion is way more accessible through sound than it is through sight. And that digital technology is so biased toward the visual. You know, we’re looking at these screens and screens are fine, but it’s like the visual always feels a little distancing, a little alienating, a little objectifying. There’s a tree over there. There’s a person over there. And through the computer screen even more so, it’s out there, you’re over there. And the things that engender compassion and connection are like song and sound and sound bath and drum circles and dancing together and those rhythms that tend to permeate. You know, I think about the civil rights movement when the police or the army would come in to arrest the civil rights people in a church. You know, Martin Luther King would say, sing. And when they sang, the cops would freeze because these people are singing and it just turns them instantly into this one large bee. How do you arrest a singing mass? You’ve got to pick them off, individuate them one at a time in order to arrest each one. So my concern with the digital originally was the emphasis of sight over sound which tended it away from an us phone and towards an I Phone, you know, everything very individualised.

Douglas: And I guess, you know, artificial intelligences, if they’re real, I still see them just as glorified algorithms. But if they even develop more, I’m mainly concerned for the ways that AI’s will tune themselves toward individuals; that the AI will play you. Rather than I don’t mind going to a concert even and there’s an AI that we’re as a group going to interact with and look at, because it’s us with that thing. But when one gets you alone, you know, it feels predatory. It feels like the lion that picks off that one gazelle. Oh, look at that one on the end of the pack, you know they’re going to get the one. And that’s bothered me about it. And we’ll see. You know, really, capitalism was the original AI. It has an agenda of its own. It wants something, it wants growth. It wants exponential growth at all costs.

Manda: And it’s busy destroying the entire planet in order to feed its growth. Yes, exactly. Somebody said that, didn’t they? You’re all worried about this AGI that’s going to make the infinite replicating paperclip using your atoms, but actually we’ve got a capitalism, it’s doing it quite well at the moment and we’re living through it.

Douglas: Which is already doing that. So if AI’s are going to be in the service of capitalism, then we’re kind of ****** right. But if we do have AI’s and they can sort of accelerate enlistment of people into various programs, then I would certainly hope we’re using it, uh, for something other than the market. But I don’t see how that happens when it’s all about money. Is AI a tool for capitalism or is it a product of capitalism? Or is it both? And I think it’s both.

Manda: It is both. Yeah.

Douglas: Which creates a feedback loop between AI and capitalism to now exponentially grow whatever this manipulation platform framework is. And I don’t like that. On the other hand, it makes apparent something that hasn’t been apparent before. I can go on CNN with Jake Tapper, and he can ask me, I mean, finally, I can get it in the mainstream media when he asks me, well, what about AI and the unemployment problem? I can say, well, what about the unemployment solution? You know, why is unemployment a problem? I don’t want a job, I want stuff, I want meaning, I don’t need work. I’m happy for the AI to do all the work if I get to do all the play. So we can actually ask the question, does everyone need to be working so much? So we’ll see.

Manda: Yes. And how does Jake Tapper take that? Because that’s not happening this side of the pond. People are not holding those conversations, at least not that I’m hearing. I don’t watch television anymore, so maybe it is, but I haven’t heard it.

Douglas: Well, they don’t invite me back after I do something like that. They think I’m pranking them, right? They think it’s pranking and it’s not. It’s the first thing!

Manda: No. We’re back to David Graeber and bullshit jobs, aren’t we?

Douglas: Exactly. It’s denaturalising power is what it is. But at least the idea of AI gets us to ask certain questions about what are we programming for? And that’s a good question to be asking.

Manda: Yes. Because it seems to me as much more of an outsider than you, that we’re caught in a kind of ideological flywheel. I was listening to, uh, Your Undivided Attention with Tristan Harris and Azar Raskin the other day, and they had on the Green Emerald guy who was talking about his theory that the evolution of AI is a failure to understand The Sorcerer’s Apprentice as a cautionary tale. But right at the start, Azar read out something from a friend of theirs who talks regularly with people who are coding AI in the heart of the beast. And he said, everything comes down to determinism, eventually, these conversations. That they are 100% convinced not only that silicon life will supplant biological life, but this is good. And that in the raging wildfire that follows, everybody’s going to die. But it’s fun lighting big, bright fires and if you’re going to die anyway, you may as well be lighting the fires. And as narratives go along the extinction plane, that strikes me as a particularly interesting one. And how has it taken off amongst the people who are who are writing this code, who believe that it’s going to take them down and are going on anyway because they don’t know how to stop. And they don’t know how to stop because they absolutely believe in the profit motive. It is a thing that they believe there is no alternative; it’s good and useful and anyway, the silicon is going to take us all over. And I wonder how do we change that narrative? When it sits so apparently tightly with people who I am guessing also have a notion of tears, but are less keen to embrace it, because if they did they’d probably lose their jobs.

Douglas: Well, even in so-called reform movements like Tristan and Asa’s humane technology, it still, I think, makes the fundamental error of seeing humans as objects. They’re not the subjects, they’re the object. So it’s how can we make technology that treats human beings more humanely?

Manda: Okay. You mean that is the question they’re asking, or that’s the one they should be asking?

Douglas: That’s the question they’re asking. Technology is treating humans humanely, like we treat cage free chickens. We raise them humanely. No, I’m looking for humans. What does human centred technology look like? It’s not how humanely can we treat people as we extract their value from them with technology. How humanely can an iPhone treat its little user.

Manda: While it’s busy destroying the lives of a dozen people in the making.

Douglas: Right. I don’t accept the premise that technology has to be anti-human to begin with, that you just mitigate its destructive effects. I don’t think you program for that to begin with.

Manda: But if it’s arisen out of and is promoting, if we’ve got this flywheel where it both arises from, is a product of and is designed to enhance the death cult of predatory capitalism, humanity, people are just noise. They’re just data points. They’re just things to be extracted from at all points, are they not? How do we step off that self-perpetuating cycle?

Douglas: Well, this is Exodus. How did they escape the death cults of Egypt? They used the plagues. And the plagues weren’t there just to convince the Pharaoh to let them go. God hardened his heart anyway. He had no free will. The Pharaoh was so evil, he couldn’t let them go. What were the plagues for? The plagues were desecrations of the gods of the death cult. So blood desecrated the Nile, which was a god. Locusts desecrated the corn, which was a god. Each of the plagues were desecrating one of the gods until you get to the New Years, which was in April. They desecrated the final god, the calf. They sacrificed the calf and put the blood on the door. So what they did was they killed their gods. And I think that’s what we have to do in order to escape from the death cult of capitalism, the God of wealth, the God of power, the God of property, the God of control, all the gods. You know, the God of acquisition; the gods that have been created for us by this cult in America. You know, I was raised to long for a car and to long for a car where the car expressed your masculinity and who you are. So am I a Ford Mustang guy? Am I a Chevy Camaro guy? Am I a Dodge Charger guy? And then you try to work and have enough money so you can eventually buy that thing. And you go back, again, denaturalise power. Where did that come from? This whole idea of owning a car as a way of expressing who you are. It was because in the 20s and 30s and 40s, you worked at a factory all day long. You worked for eight hours at the factory, then the whistle blew, you got off work, you got a beer and a newspaper and hopped on the streetcar, had your beer read your paper, talked to your friends until you’re home. With the invention of the car, they said, how are we going to get this guy who’s been operating heavy machinery for eight hours and then has a beer? How are we going to convince him that instead of having a beer and a good time with his friends, that he should get behind another piece of heavy machinery that he’s going to pay for and spend one day a week working just to pay for this vehicle and drive it for an hour home. How are we going to do that? And they did it. They created the false god of independence and automotive masculinity and all. And now it’s one of our things.

Douglas: So how do you desecrate that? How do you break that? Not by transforming it into a Tesla. You do it by saying, where am I going? Why is my work an hour away from my house? Oh, because GM influenced the zoning of the whole area to put it that far. Where’s the streetcar? Oh, they took away the streetcar because it’s a public utility and we want private sector things. So then you keep looking and you go, wow. So even in California with this tunnel that Elon Musk was promoting, you know, with The Boring Company, they were going to have an underground speed thing that you put your car in. It was one of his big inventions. Now we see why he did that, and this has been been documented by Paris Marx, was because they were going to build a high speed light rail train from San Francisco to Los Angeles. They had to stop that or you’re not going to sell as many cars, so they create this whole fake BS project of an underground car moving transport system, which was going to revolutionise transport up and down the coast to get the funding away from that. It’s like, oh, so this is the world we live in. But yeah, so what we have to do is kill our Gods. We have to desecrate our gods so that we can be here with each other and that’ll change our priorities. But that’s the way we get out of a death cult.

Manda: How do we do this, Douglas? How do we show up the clay feet of the gods and make them no longer worth the awe that they are given just now?

Douglas: Two ways. I mean, it’s all I’ve been doing. Is denaturalise power. Tell the story, show where the things came from. And while you’re doing that, rather than just letting people wake up into what might seem like a nightmare to them, you also, um, uh, offer people the alternative. Which is, I was going to say ecstatic ritual, but you know, if they don’t want ecstatic group ritual, that’s okay. Friendship, sex, connection, compassion. You know, sitting with other people, learning who’s in your neighbourhood, service to others. I mean, I don’t know why people don’t get off on it, they think it’s crazy, but you can get so much pleasure.

Manda: Because they’re watching their phones and scrolling through for the next thing and ignoring all the people around them. I don’t know if you listen to Nate Hagens, but he just got home from India and he said, in India, all these people were hugging him and talking to him. And he got off the plane in Minneapolis somewhere, and he parked his car 45 miles away, and he sat in the car, 50 minute drive, and nobody talked to anybody else. I’m sure they’re all scrolling their phones, checking whatever they’d missed while they’d been on the plane. It’s there’s going to be hard I think. I mean, because I hear you and I think we’ve got connections online. We’re making a connection here. There’s connections of passion and purpose as well as connections of place communities. But somehow the serotonin mesh of that connection has to be worth more than the dopamine drip of the scrolling.

Douglas: Yeah. And there’s so much risk now in connection. You know, any free conversation, especially among us progressive types, you’re always at danger of saying some cancellable thing. Of offending somebody. It’s a really hard environment. Oddly enough, I find in America people on the right are much more gregarious and open, free to speak and friendly, right? The volunteer fireman, the gun owners.

Manda: Are the firemen on the right in the US? Because in the UK the most left wing union is the Fire Brigades Union.

Douglas: Oh, no. Well, we’re mostly volunteer firemen where I’m living, but no, it’s more the blue collar guys do that. There’s a fireman’s union. But our unions aren’t even left here.

Manda: Yeah, some of ours aren’t either, to be fair. We need to stop in a moment, but I’m just intrigued with this: I spend a lot of time listening to people on the left going we just need to talk to the other side, we just need to listen to the other side. And I’ve never met anyone on the right who thought it was useful in any way to talk to anyone on the left, other than to shout at them and tell them how they were wrong. And I may be massively generalising and that may be wrong, but my experience, my quite limited experience of people on the right, is that they feel they’re winning. They feel quite secure. Their amygdalas are not as triggered. I remember way back in 2014, there was a really interesting functional MRI study done, I think, at Stanford, where they they took some self-declared Democrats, self-declared Republicans, they did an MRI and the Republicans amygdalas were significantly p less than 001 bigger than the Democrats. And I have a strong suspicion that if you did that study again now, it would be the other way around. That a lot of people on the left are feeling consistently under threat (left, progressive, whatever); people who understand that we’ve just lost nearly a point one of a PH point in the oceans, and that is that means the buffer is dying. It’s ****** terrifying. And all the rest. We’re reading this stuff, and I can feel my amygdala pinging half a dozen times a day, whereas my friends on the right are watching the rightward move of politics around the world. They don’t believe in climate catastrophe. They don’t believe in the sixth mass extinction. They don’t really care about AI because it’s not a thing in their world. And they’re feeling quite peaceful, actually.

Douglas: I know it’s tricky. How do you eat the fruit of the tree of the knowledge of life and death and not freak out, right?

Manda: And not go mad. Yeah, yeah.

Douglas: You know, that’s the thing I’m working on now. It’s funny, I’m just going to go to LA in three days to work on a documentary, which is almost like a documentary, sort of a Spalding Grey like monologue documentary where I want to try to talk America down off its bad trip.

Manda: Oh gosh, Douglas, I hope that works. If it works in the US, it’ll work everywhere else.

Douglas: Yeah, exactly. Well, the West anyway. Yeah it’s tricky. I feel like it’s the best service I can offer at this stage, is like how do we get off that? Because it’s tricky. Usually with a bad trip, you just tell people the bad things not actually happening; you’re hallucinating. Everything’s okay. But here the bad trip is partly because it is happening.

Manda: Denial is only useful so far, and it’s breaking down as a strategy in real time. So yeah. Okay, okay. I look forward to seeing your documentary.

Douglas: You talk to a Tyson Yunkaporta, I don’t know if he’s been on your show, or an indigenous scholar and they’re not as worried. Whenever I talk to him about this, he says, oh civilisations come and go.

Manda: So do mass extinctions. But it’s just sad.

Douglas: We’ve seen a bunch. I guess maybe it’s hubris to think that our civilisation will take will take the whole thing down, right? Yeah. It is sad.

Manda: Probably we’ll only lose 98% of species and the ones that survive will be all the bacteria and the mitochondria and all the things that will evolve back.

Douglas: If they can. If it’s just bacteria and mitochondria the heat conditions on the planet might be such that we can’t.

Manda: I meant amoeba. It’s been very hot before. And you know, the things in the very depths of the Marianas Trench do survive. You know, in geysers in Iceland, they survive because they used to it being very, very hot. And eventually something else will evolve. It just seems a bit sad that we’ve got this far and we’re busy trashing it, because we can’t get our heads around being nice to each other.

Douglas: I know.

Manda: Anyway. All right, I look forward to your documentary. And I kept you here much longer than I intended. It’s been fascinating. And I love your enthusiasm. And I love your hope for the future and your awe and wonder and connectivity, Douglas. Thank you so much for coming on to the podcast. Was there anything you wanted to say as a last thing to people listening?

Douglas: Thank you. Oh, I love you all. And let’s see what happens. This is going to be interesting.

Manda: Yeah. We are here at the most exciting period in the history of humanity. So there’s got to be something for that. All right. Thank you.

Manda: So that’s it for another week. Enormous thanks to Douglas for all that he has and does. And if you haven’t listened to Team Human, if you haven’t read his books, I will put links in the show notes, and definitely they are all worth checking out. And he’s right, obviously, building communities of place and of passion and of purpose are what’s going to get us through. They’re probably one of the very few things guaranteed to get us through. And as he said, and we didn’t unpick in huge detail, we are really near the edge of the cliff now. So if there’s stuff that you can do to build your communities locally, then please find ways to make it happen. And that apart, you can always introduce people to the podcast because somehow around the world, we are also creating communities of purpose and of passion between ourselves. Coming to know what’s possible, where the edges of our thinking lie, where the possibilities begin to open up in ways that take us away from the death cult, out of the current system to something that we don’t necessarily understand, but that we can begin to build. So there we go.

Douglas: That is it for this week. We will be back next week with another conversation. In the meantime, enormous thanks to Caro C for the music at the Head and Foot. To Alan Lowell’s of Airtight Studios for the production. To Anne Thomas for the transcripts. To Faith Tilleray for keeping track of all the tech, and my goodness, it is getting complicated; and for the conversations that keep us moving forward. And as ever, an enormous thanks to you for being there, for caring, for giving us the time, for listening and for sharing. If you know of anybody else who wants to explore the depths of what we could be as humans, then please do send them this link. And that’s it for now. See you next week. Thank you and goodbye.

You may also like these recent podcasts

Call to Adventure! Crafting an Integral Altruism with Jonas Søvik

What is Integral Altruism and how could it crowd-source the answers to our meta crisis?

It’s a while since I learned about ‘reverse mentoring’: a young person mentoring someone of an older generation. The idea really took hold, so when a mutual friend connected Jonas Søvik and me, I knew I’d found someone from whom I could learn a huge amount about life, ideas, thoughts and how the world feels in circles I would otherwise never reach.

Honouring Fear as Your Mentor: Thoughts from the Edge with Manda Scott

Manda dives deep into the nature of fear, what it is and how we might find our own resources, resilience and capacity to work with the parts that catch our attention. Given this, it is recommended that you listen at a time and place where you can give it full attention.

Co-ordiNations vs the Network State: Greenland and the Schism in Global Vision with Dr Andrea Leiter

What is a Network State and how does the concept matter in relation to the Trump administration’s attempts to take Greenland – and their ‘peace’ proposals in Gaza and Ukraine?

Tracking the Wild Things, Inside and Out – with Jon Young of Living Connection 1st

How can we step into our birthright as fully conscious nodes in the Web of Life, offering the astonishing creativity of humanity in service to life? Our guest this week helps people do just this…

STAY IN TOUCH

For a regular supply of ideas about humanity's next evolutionary step, insights into the thinking behind some of the podcasts, early updates on the guests we'll be having on the show - AND a free Water visualisation that will guide you through a deep immersion in water connection...sign up here.

(NB: This is a free newsletter - it's not joining up to the Membership! That's a nice, subtle pink button on the 'Join Us' page...)