#254 Of Reindeer, Donkeys and the verb that is Water – stories of climate-healing with Judith Schwartz, author of The Reindeer Chronicles

How do we move beyond our myopic focus on carbon/CO2 as the index of our harms to the world? What can we do to heal the whole biosphere? And what role is played by water-as-verb, forest-as-verb, ocean-as-verb?

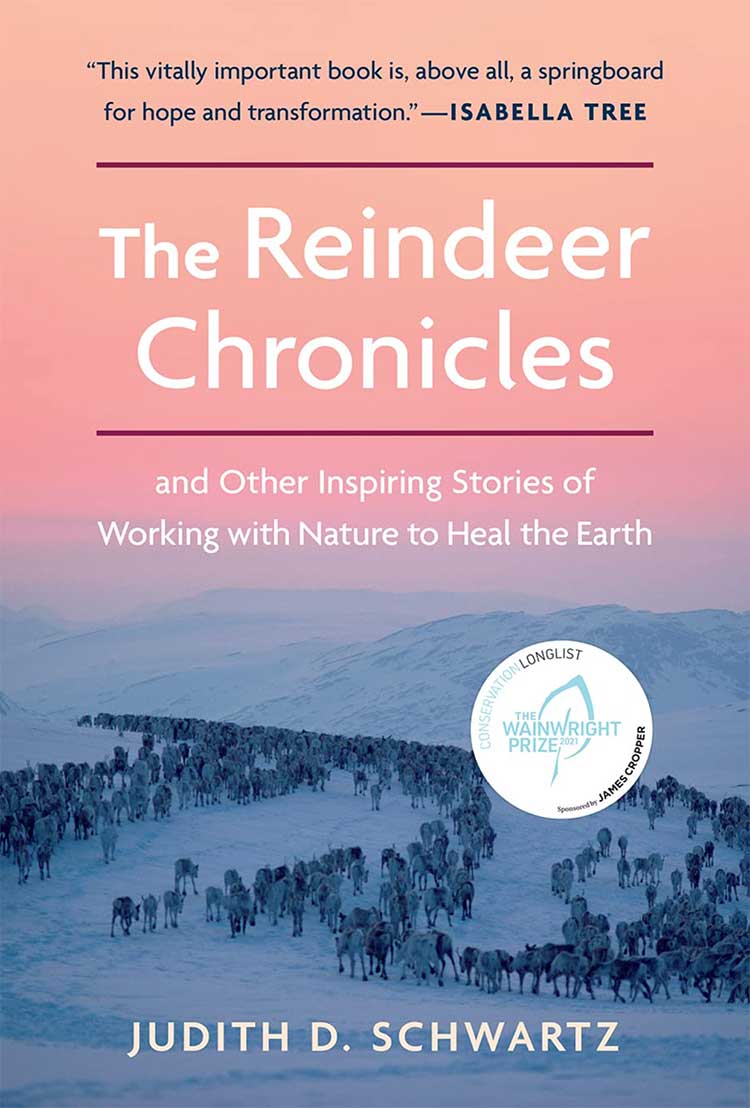

This week’s guest is an environmental journalist and author who has answers to all of these questions – and more. Judith Schwartz is an author who tells stories to explore and illuminate scientific concepts and cultural nuance. She takes a clear-eyed look at global environmental, economic, and social challenges, and finds insights and solutions in natural systems. She writes for numerous publications, including The Guardian and Scientific American and her first two books are music to our regenerative ears. The first is called ‘Cows Save the Planet’ and the next is ‘Water in Plan Sight’. Her latest, “The Reindeer Chronicles”, was long listed for the Wainwright Prize and is an astonishingly uplifting exploration of what committed people are achieving as they dedicate themselves to earth repair, water repair and human repair.

Judith was recently at the ‘Embracing Nature’s Complexity’ conference, organised by the Biotic Pump Greening Group which offers revolutionary new insights into eco-hydro-climatological landscape restoration. She’s a contributor to the new book, ‘What if we Get it Right?’ edited by Ayana Elizabeth Johnson, who was one of the editors of All We can Save.

Judith has been described as ‘one of ecology’s most indispensable writers’ and when you read her work, you’ll understand the magnificent depth and breadth of her insight into who we are and how we can help the world to heal.

In Conversation

Manda: Hey people, welcome to Accidental Gods. To the podcast where we believe that another world is still possible and that if we all work together, there is time to lay the foundations for that future that we would be proud to leave to the generations that come after us. I’m Manda Scott, your host and fellow traveller in this journey into possibility. And this week’s guest is someone I’ve wanted to speak to for a long time; an astonishing author, an environmental journalist and activist, and all round really inspiring individual. Judith Schwartz has written for publications including The Guardian and Scientific American, and her first two books are music to our regenerative ears: Cows Save the Planet was the first one, and the next was Water in Plain Sight. Her latest, The Reindeer Chronicles, was longlisted for the Wainwright Prize and is an astonishingly uplifting exploration of what committed people are achieving as they dedicate themselves to the repair and healing of the earth, of the water, of themselves and of each other. Judith is a contributor to the new book What If We Get It Right, which is edited by Ayana Elizabeth Johnson, who was one of the editors of All We Can Save.

Manda: And I’m kind of guessing you read that a while ago. She was recently at the Embracing Nature’s Complexity conference organised by a group called Biotic Pump, which offers revolutionary new insights into eco hydro climatological landscape restoration. And you too are welcome to try saying that at the end of the day. Judith has been described as one of Ecology’s most indispensable writers, and when you read her work and you definitely should, you will understand the magnificent depth and breadth of her insight into who we are and how we can help the world that we love to heal. So this was an immensely generative, beautiful, thoughtful conversation that roamed far and wide and has left me feeling really quite uplifted. And I hope it does the same for you. So people of the podcast, please do welcome Judith Schwartz, author of The Reindeer Chronicles and so much more.

Manda: Judith, welcome to the Accidental Gods podcast. How are you and where are you this lovely autumn morning?

Judith: I’m well, and I’m in Bennington, Vermont, where we are also having a beautiful, beautiful day. It’s a little bit warm for my liking, because my wiring is for how the climate used to be.

Manda: Right. And it wouldn’t be warm at this time of year? Or it wouldn’t be as warm at this time of year.

Judith: It would be a different flavour of warm. There would be a briskness to the air.

Manda: Right, right. That sharpness that September brings. Yes. I remember going outside to do the ponies sometime a while ago thinking, God, it’s really nice for September. And then my brain caught up, because a little bit fogged in the morning, so oh no, no, hang on, it’s June. It’s not meant to feel like this now. And now it’s September and it doesn’t feel like September either. So you are many things. You’re a journalist, you’re an author of astonishing books, and you speak at what sound like some of the most interesting conferences I have ever heard of. In all of those things. What is most alive for you at this moment?

Judith: Yeah. So what I’ve been carrying lately is an understanding of climate possibilities beyond the focus on carbon. And one reason that this is so alive to me is that in my own community, I’m seeing what happens when the focus is only on CO2 concentrations. And when that’s all you see, what’s left out is all of the processes that nature uses to regulate our climate.

Manda: Not to mention all of the other things that are contributing to the meta crisis. The PFAS in the rain, the microplastics in the clouds, the AI that potentially might be going to eat us, the fact that social media are destroying the emotional lives of the people they are meant to be bringing together. If all you focus on is the carbon, then the rest goes out the window. You have a lovely story in one of the papers that I read, and that I will put into the show notes, people, it will be there. Of a dog that you had, which was a brilliant metaphor for this. Can we use your dog as a lead in to how we might look at this differently? Just tell us that little story.

Judith: Sure, sure. So we had a wonderful pit bull named Tembe, who was very high spirited and very tough. And I remember when I might take a walk with her and she would see a rabbit and get all excited. And what was so interesting to me is that her nose would be to the ground, and she was searching for that rabbit, but because her nose was to the ground, she wasn’t noticing that the rabbit actually just fled away. And had she glanced up, she would have been able to at least chase it more effectively. And it occurred to me that that’s kind of what we’re doing with climate; that we are so focussed on carbon, on CO2, that we are missing the real story of climate. And actually, I think it’s useful to think of many stories of climate are operating simultaneously. It’s not just one story.

Manda: Yeah, brilliant. I had a working cocker spaniel who was just the same. She put her nose in a scent and her entire world focussed on the scent and exactly that. A squirrel could hop across two inches in front of her nose and she wouldn’t notice it was there, because scent is everything. And we have got to the same place, or at least our policymakers have got to the same place. We were talking a few weeks ago on the podcast to Mary Booth of the Partnership for Policy Integrity, about the fact that there is a business in the UK that is cutting down very old, old growth forests in the US and Canada. They have factories now on site that will turn this wood into pellets, and then they ship it across to the UK, and they claim not only that it’s carbon neutral, that this is helping to get us to net zero because it’s neutral. They’re claiming that because they plant new trees, it’s actually carbon negative. And every single part of that narrative is both intellectually and emotionally and morally wrong. And yet there is a market in carbon.

Manda: And we on the podcast refer to the death cult of predatory capitalism. And it seems to me that the Death cult is just kind of absorbing narratives of climate change in order to maintain its own momentum and to keep itself going, while we are like Wile E coyote right out across the canyon and and some of us are looking down and they’re trying not to. So in your world and your work, particularly in Reindeer Chronicles, which I have now read three times, and it’s an amazing book and it’s so inspiring. But there seem to me to be people who get this and people who don’t. And I don’t like putting the world into binaries and us and them, but nonetheless, this is the case. In your explorations of the world, you go and talk to extraordinary people in extraordinary places. Are more of them understanding the complexity? That it’s not just about the carbon. And in fact, from what I’ve been understanding of what you’re writing, that water is really important and the biotic pump and everything that we can do with it. Is that a narrative that’s beginning to sink in at a policy level or not yet?

Judith: Not yet on a policy level. And one challenge is that carbon is easier to measure than, say, how the water cycle is functioning or how forests are functioning. Note that I use the word functioning, which is a verb, so we can think of water as a verb. Or forests as a verb. And in doing so, that opens up the possibility to really grapple with how things work. So I feel that more people are getting it, but at the same time, I think that there’s such an opportunity for people to understand how nature works. Again, Nature is a verb, not just a noun. As a colleague of mine, kind of an eco philosopher, Peter Donovan says: nature doesn’t just sit there and look pretty. It does work.

Manda: It’s living. It’s always living. It’s an emergent process of life.

Judith: Absolutely. And to see that, we only need to open our eyes and ask questions, and how I often think about it is to reconnect with your inner eight year old. That all of this that I’ve needed to do years of reporting and research to understand, it didn’t come naturally to me. But all of this is intuitive. The understanding of nature and how it works, and how it is regulating the climate for us all the time, as well as doing all kinds of other things; that somewhere we know it.

Manda: Yes. And indigenous peoples know it anyway. Vanessa Andreotti is very clear that English is 70 to 80% nouns, and their indigenous language is 70 to 80% verbs. And exactly as you said, water is a verb, forest is a verb, ocean is a verb. Everything that happens out there is alive, and we are an integral part of it. We just kind of have blinkers on. So in service of helping us take the blinkers off, can you explain a little bit about the biotic pump; about the function of how things work when they’re working in a healed and whole way? When a forest ecosystem is helping to maintain climate and cool and cycles that we rely on. Because this is something that, until I read your work in depth, I kind of thought I had an overview and actually I didn’t really understand it at all.

Judith: Sure. Well, let me step back a little bit and explain where the biotic pump understanding comes from. So there is a Russian theoretical physicist named Anastasia makarova, and she and her late mentor, Viktor Gorshkov came up with this understanding. And what happened was they were asking a basic question. And that question was, okay, since we understand that all of our moisture ultimately comes from the ocean, all of our precipitation comes from the ocean; how then do we have rainfall when we’re hundreds or even thousands of kilometres away from the seas? So what they came to see, using the tools of physics, which are way beyond my comprehension and their work involves very intimidating looking equations and symbols and this and that. But eventually it gets down to English. They are very effective in that. They came to understand that forests are moving moisture horizontally. So it comes from what water does, how water works. And if we think about infiltration, that’s one thing. Water infiltrates and is held in the land, when the land is healthy, when the soil is healthy and alive. And then there’s evapotranspiration.

Manda: Can you unpick that?

Judith: Yes. Okay. Well, let’s just say transpiration. Evapotranspiration includes the surface of the Earth, but transpiration is the upward movement of moisture through plants, through vegetation.

Manda: Right. So draw it up through the roots and it goes out through the leaves or a leaf equivalent.

Judith: Yes. So trees, all plants transpire. But trees are super transpirers because they’re bigger, because they have all that leaf surface and all of those leaves photosynthesising and releasing moisture through the stomata. And when you have a concentration of trees, as in a forest, an intact forest, there’s lots of transpiration happening. So all this moisture is moving up into the atmosphere. There are two things that are important (Well, many things that are important). One is that is a cooling mechanism. So basically that’s changing liquid water to water vapour, which is what we do when we put on the kettle. And we know that that uses energy, so that consumes energy. So the trees are basically harvesting heat and releasing it as latent heat embodied in water vapour. Now it doesn’t just stay there, as we know, there’s a mirror process, mirror to transpiration, which is condensation. And at that point heat is released. Now, with all that concentration of transpiration happening, that creates a low pressure zone. So there’s a kind of almost void which pulls in moisture from elsewhere, ultimately from the ocean. So we’ve got forests moving moisture horizontally. So that’s a really important function. So that is the biotic pump. And what Makarieva and Gorshkov had theorised was that when the biotic pump breaks down, rainfall will cease. And that is what we are seeing happening in real time in the Amazon rainforest.

Manda: I read today earlier that there is now drought in the rainforest, and a rainforest that hasn’t known drought in the entirety of of human understanding. There has been no drought. It’s a rainforest, it’s not designed to be in drought. So is that happening now because a critical mass of the rainforest has been cut down?

Judith: Well, the Amazon rainforest is huge, so there are areas where it’s functioning. Then there are areas where it is breaking down, and it’s from the loss of the forest, from deforestation, but also forest degradation.

Manda: Right. Tell us more about that.

Judith: So it’s not just that there’s clear cutting, but maybe the loss of trees, loss of health of trees. So the degradation of that system. And one thing that Makarieva points out is that for the biotic pump to function, it needs to be a mature forest. And at the conference that I attended and took part in in Munich, called Embracing Nature’s Complexity, about Biotic Pump Science and communicating Biotic Pump Science, what she really brought home to us was an understanding that there is knowledge in a forest ecosystem. So these trees evolved and established relationships underground through the root system, through the mycorrhizal fungi that are allowing trees to communicate and to share resources like water and nutrients. So that’s really important and kind of bolstered my respect for forests. So if we think of forests as a bunch of sticks of carbon, we will interact with that forest in one way. And it would be like, okay, if we cut down a bunch of trees but we plant other trees, then our carbon equation is fine. If we understand that the forests are engaged in this process of the biotic pump, that forests are a pump and that the capacity for that pump to function has evolved through the life of that forest, then it’s different. And I want to just mention, because this isn’t often talked about when people talk about the biotic pump, and I’ve only recently come to understand it; that the biotic pump also has a really important implication for climate when we’re thinking specifically of temperature. So when I mentioned that the forests are harvesting heat and releasing it higher up in the atmosphere where heat is released. Now, that is if the biotic pump is functioning. Again, if the biotic pump breaks down, then the condensation happens lower down, and heat is released where it is interacting with greenhouse gases. And that makes intuitive sense, because I’m old enough to have lived in a time when the weather wasn’t so weird. So in my bones I feel it when it’s different. And there is a sense of something hovering closer to the earth, like the biotic pump not working and, you know, the weather is just kind of stuck.

Manda: Yeah. And along with that, one of the factoids in one of the papers that I read, was people testing the different temperatures, and they were getting a 30°C difference between the roof of a house and a tree that was at the same height. And then other people have tested grass in an old growth, regenerative paddock, and then short grazed dry grasses and then a tarmac road. And again they’re getting 10 to 20 degree differences, and some of these are liveable and the others basically are not. So we were talking about policy at the beginning. And reading your book, you’re going all around the world from very hot places up to the Sami and the reindeer, and in each case there seemed to be people on the ground who really get it, who are doing amazing things. And then people who have the responsibility of governance, who either willingly or unwillingly don’t get it. And I ask this a lot of people on the podcast, and nobody is really able to answer it. So if you can’t answer it, it’s fine.

Manda: But it seems to me what little I know of the politics in this country. So people like Ed Miliband, he ran quite a fun podcast while he was not in government, and he really seems to care. He kind of gets it insofar as he can. And he definitely wants to make the world a better place. And yet, I have no doubt that he thinks Trax is a wonderful thing, because someone has told him that it’s contributing to our net zero, and this is what matters. How do we change the narrative at a policy level? Is there anybody who’s working on that in a way that actually works, that is actually going to get through to say, Tim Waltz and Kamala Harris, please goodness, that they end up on November the 5th having the 400 electoral votes swamp that I read today was possible. How do we get through to people at that level? Have you got people that you know of who are working at the narrative stage of that? Or is it just impossible to break through that kind of, I don’t know, concrete ceiling?

Judith: I don’t think it’s impossible at all. But I believe it needs to start with people. I think it’s a trickle up. I mean, it is interesting how ideas move through society and how it does so seamlessly, in that there’s not necessarily a moment that, oh, we understand that the water cycle drives the climate and so let’s now work to restore the water cycle. But when it happens, it’s as if it’s always been an understanding. And that’s what I mean by seamlessly. My first book in environmental journalism was about soil.

Manda: Yeah. Cows saving the planet, I love it.

Judith: Cows save the planet and other improbable ways of working with soil to heal the Earth. And I remember getting emails back from editors: soil and climate? No, I don’t think we’re interested in that.

Manda: Curses!

Judith: Yeah. That doesn’t touch my…

Manda: It doesn’t ring the bell

Judith: Exactly.

Manda: But now it would. Regenerative Ag is huge. There’s films, there’s books. It’s, you know, Gabe Brown and Roots So Deep. It’s a big thing now. You were just a bit ahead of the curve.

Judith: That’s what I mean, that there’s never any moment.

Manda: Where it suddenly became the in-thing. Right. And water. Because your next book was about water. So did you have the same pushing up against the river to get that published, or did they listen?

Judith: Absolutely. Oh, not published, but get listened to. Again, I wrote to many publications saying please write about this, and explained it and how the water cycle… I mean, basically, if you step back and ask yourself, how does the earth manage heat? It comes down to the phase changes of water, and I don’t think anybody would argue with that. But then somehow we got caught in this carbon narrative. But one thing I want to respond to when you mentioned the temperature differences of land, of where there’s vegetation and where there’s a roof; I said that there are many stories of climate, and sometimes what I think about is, or I talk about, is how one story of climate is the story of what happens when solar radiation strikes the Earth. Does it hit asphalt and become sensible heat? Or does it meet vegetation, meet life and is then taken up through photosynthesis and incorporated into life forms? So plants and then the plants are engaging with all the microbial life. And then animals are eating.

Manda: Or in the ocean where the phytoplankton are the basis of the food chain. I remember listening to Tom Chi a while back, a super bright guy, very invested in business, but he has a scale of from 0 to 3 of the evolution of business. And he said everything comes down to how many bounces a photon has, because it is our energy source and until the sun burns out, which is not going to be in a time frame we need to worry about. It either, exactly as you said, it hits maybe a white roof and bounces straight back, or it hits something else and perhaps asphalt, and then it’s a bit warm and if you’re really cold, you could lie on the asphalt and that’s it. Or exactly as you said, it hits a tree, it hits a plant, it gets absorbed, it gets turned into energy, which might then be eaten by something else, which might then be eaten by something else and something else, and it transits. Or it might hit a solar panel and get turned into power, and then that power is used and then it’s gone. And how can we begin to think about maximising the use of every photon in a way that isn’t destroying the rest of the ecosphere? I find that a bit of a reductive way of looking at things, but it’s at least interesting that somebody who is inherently reductive and allied to business is thinking about that, instead of just thinking about how do we monetise carbon, which is a bit frustrating. Okay, let’s take a slight step in another direction. I’m sure everything will loop back together. You have degrees in journalism and in counselling and psychotherapy. And it seemed to me, reading the book, that a lot of the work that you write about is as much about helping the people to heal, and the relationships between the people to heal, as it is about healing the land. And there was a particular story, Jeff and Bob Chadwick, and I was very taken with that.

Judith: Oh, right. Jeff Goebel and his mentor was Bob.

Manda: Yes. And I remember Jung has a story, richard Wilhelm I think, who ends up in a place in China and there is climate chaos just because there’s chaos, and the Taoists try and do something and the Christians pray and nothing happens. And somebody eventually says, we’ll just need to get the wise man and goes off and brings the wise man back. And the wise man sits for three days and says, you all leave me alone. And then the rains come. And Richard Wilhelm goes to him and says, well, how did you do it? And he says something along the lines of The Tao was out of balance here. I come from a place where the Tao is in balance. I just needed to get the Tao back into balance. And Bob and Jeff in your book are more or less doing exactly this. Bob particularly comes into a group of people who are quite fractious, and there’s a lot of difficult energy. And he basically says bringing you all together is going to make it rain. And Jeff is horrified, you know, why are you making predictions like that? You’re going to completely destroy our credibility.

Manda: And they get them all to function together and it rains. And I was so encouraged by the fact that this isn’t just something that Jung mentions from some Taoist sage in China; it works in our culture and our time. And that what we need to do is find the ways to bring people together. And I really loved that section of the book where you’re in New Mexico and it’s very easy to imagine watching tribalism happening now, because it’s an election time. You’ve got basically two lots of people, the ranchers and the people who are in control of the water, and they hate each other, and they’re getting to the point where bullets are flying around and nobody’s dead yet, but it’s not going to be long. And you manage to bring them together. So that’s me talking for a long time, but I was just wanting to bring us to there. And to what extent do you feel that the healing of the people is the healing of the land? Is that a narrative, or am I just picking that out of what I’ve seen because that’s a belief system that I hold?

Judith: Absolutely. So there’s a filmmaker that I write about named John D. Liu, and I love how he says that our landscapes are a reflection of our consciousness. And it goes both ways. It’s hard to be physically and spiritually healthy and vibrant in a degraded landscape. I mean, we all kind of intuitively know that when we’re in a healthy, beautiful landscape, be it a forest, the coastal area, we feel good.

Manda: Yeah, we go to the sea when we want to relax, right? Or we go into the mountains. One or the other.

Judith: Yeah, right. And in healing landscapes, we are healing ourselves. We are connecting with nature. The healing, you see it, you feel it.

Manda: That’s beautiful. And one of the ones, I think it was Jeff again, he went to a group and he said, okay, what are you afraid of and what’s the worst that could happen? And then what’s the best that could happen? And then he asked a really specific question: using non-Western methods of agriculture, could you increase your output by 10%? And they’re like, yeah, no problem. Could you increase it by 20%? And they said, maybe. Could you increase it by 50%? Absolutely not. And then he asked what I thought was a genius question: he said, okay, definitely can’t do it, so take all the pressure off. If you were thinking about trying to do it, what would you do? And they all came up with ideas. And he goes back a few months later, I think.

Judith: 15 months later. This was in Mali.

Manda: And they lined up along the road to greet him, because they’ve managed to increase their production by 78%, having said 50% was impossible! And the skills of encouraging people to do that strikes me as huge. But I also then would like to go back to that Land in 10, 20, 30 years. Have they increased production using non-Western methods? But are they working with the land or are they acting at the land? If that distinction makes sense. On the basis that Western industrial agriculture is imposing on land, to say maximise production, we don’t really care if anything else happens. We can poison the water, we can turn the soils into basically inert, growing media, but we’ll get production of something. I’m assuming these people were producing good stuff in a way that was harmonious with the land. Am I right?

Judith: It’s been a while. So I think that this was a series of workshops that Jeff did in Mali, when there were 12 warring tribes and food insecurity was 85%. I know that as he’s been in touch with them through the years, those habits and what they learned did stay, did continue. And I believe that they did continue to hold community meetings in this new way, this new, more collaborative way. I just don’t know for sure because there are so many other forces. I don’t know.

Manda: A lot of variables. Yes.

Judith: Yeah. There really is a magic that happens. The pivot for me, when I’ve looked at many of these cases and been involved in workshops myself is: given that it’s impossible, if it were possible, what would you do? And once you say, ‘given that it’s impossible’ it takes the pressure off, then you can engage your imagination. Well, if it were possible, I’d do this. And I got so enamoured of this, so excited about the possibilities, that I set up a website dotheimpossible.earth and a group of us are looking for ways to bring this consensus process to anybody who’s interested.

Manda: Oh, tell me more about that, because I hadn’t found that one. So dotheimpossible.earth, I’ll put it in the show notes. What’s happening with that?

Judith: Well, it’s very much a work in progress. We’re figuring out how to do it. And basically after the book came out, it was Covid time, and Jeff put together a consensus institute online with people in the US, the northeast, and a lot of people out West and people in Australia, because those were the people who were the groups that were particularly interested. And then many of us have decided we want to just keep this work going. So there are two main components. One is, as I described, or you explained, what is the worst possible outcome. And the reason that that is asked first is that often we hold that fear, we might not even be conscious of it, but we’re kind of paralysed by what we fear could happen.

Manda: And we don’t want to give voice to it. But when we’re given the opportunity to give voice to it amongst others and discover we’re not the only person who holds these fears, it’s incredibly liberating, I imagine.

Judith: Absolutely. And in our own kind of body and psyche, that frees us to open up to other possibilities, then it’s the best possible outcome. Then it’s ‘if it WERE possible’. So the belief systems get kind of opened up, get freed. So it’s challenging the belief that it’s impossible. Or the belief that I’m helpless. So it works on belief systems. Then the other really really important component. And this I think is important for all of our Land challenges, because it’s all about humans and relationships and our fears and our stresses. So listening to others is crucial in this process. And the flip side of that is when someone feels that they have been heard, their capacity to engage, and how conflicts kind of take a different shape. Because when we feel that we’re not being heard, then we’re constrained. And if we feel that people have power over us, then we feel frustration towards that power. And that doesn’t lead to a scenario where people can work together.

Manda: And so much of the politics of our world, your country, my country, half of Europe, it seems to me that a lot of the enraged reacting and moving into rage filled political spaces, is because there’s that lack of agency. Sarah Slaughter, who’s an amazing Equusoma practitioner, talks about feeling felt and getting gotten. And what I loved about what you were describing in the book, that Jeff does again in the southwest, was he had two people on opposing sides sit and talk to each other, and he had two other people reflecting what they were saying in the moment, so that they knew they had been heard. And that seemed to really shift things. And I’m wondering, there were a couple of other stories in the book, The Reindeer Chronicles that it takes its name from, was a young Sami man who had been told he had to cull most of his reindeer to the point where he wouldn’t be able to survive. Ecologists had decided there were too many reindeer, and then other ecologists had decided they were wrong. But nobody had asked the Sami who rely on them. And it seemed an occasion where the people whose lives are most impacted were not being heard and getting gotten. Have they been heard since? Have you heard anything since you wrote the book?

Judith: Well, what’s happening now is that there is much greater attention to the actual dynamics, the ecological dynamics. I mean, this is Norway that I was researching. And I think that the general culture is listening more to the Sami, as they are kind of at the forefront of climate related changes. But it could be more so, because I believe the Sami have more to teach the rest of us about how the animals interact with the land and how humans can best manage those animals. So just to kind of bring listeners up to date on this, is that the government was mandating the culling of reindeer because they believed that there were too many reindeer and that was impairing and threatening the fragile tundra ecosystem. But what they didn’t understand is that the reindeer were actually maintaining this very cold ecosystem. So in the summer, browsing and grazing, the reindeer were managing trees. So there’s a phenomenon under the changing climate in the far north called shrubification; that because it’s warmer, what would have been small shrubs are growing bigger.

Manda: And then it’s darker.

Judith: Right. And so that’s absorbing heat.

Manda: Yeah. And you’re losing the albedo effect. You’re doing both. You’re absorbing more and reflecting less.

Judith: Exactly. So the reindeer are browsing on the shrubs and small trees. So. Yes. So the heath, the lighter coloured grasses, the heath dominates and you get more reflection. And then in the winter months with the snow, the animals the reindeer are moved in vast herds, the herders bring their animals together and they’re moving across the landscape in tremendous numbers. So all that trampling presses down the snow pack. And that sounds like a negative thing. Don’t we want that nice fresh snow? But that snow pack actually was an insulator.

Manda: Okay, Like an igloo.

Judith: Right. So it was protecting the soil from the extreme cold, right? Whereas when the reindeer are pressing down the snowpack, then the soil is exposed to the cold, and that’s keeping the ground frozen. so the government didn’t understand that.

Manda: Yeah. It seems they’d got a Western narrative of overgrazing, which is, you know, when we put 100 cows on ten acres, they will overgraze it completely. But this is a whole ecosystem where the reindeer have been part of the ecosystem for presumably centuries, if not millennia.

Judith: Right. So, yeah, I do a lot of work on how animals are governing; what their ecological impact is because it’s not always obvious, like the reindeer, like donkeys in Australia.

Manda: Like the donkeys in Australia. Tell us, because that’s so interesting. The concept of megafauna. We want we want original indigenous megafauna, but sadly they’re all gone. But we don’t want introduced megafauna because they are bad, because we’ve got this kind of bizarre idea of colonialisation and yet the donkeys are actually fulfilling a really interesting niche. Tell us a little bit about that and then tell us, have the government got their head around that one?

Judith: Okay. So that’s another work in progress. So I’ve been exploring and writing about a family, the Henggelers who manage an area of land in the Kimberley. So this is like the outback of the outback. It’s extremely remote.

Manda: And it’s huge.

Judith: It’s an area of land the size of Singapore and one can only get there by helicopter. So it’s Chris Henggeler who I generally talk to. Their product is restored land. That is the purpose of what they are doing. And they’ve been doing that with cattle. They’ve been doing restorative, holistic grazing and have improved the land markedly right from the early 1990s. One challenge with an audio podcast is I can’t show you the before and after pictures, but you can certainly look up Kachana Station. So anyway, they were doing their work with the cattle and then the donkey showed up. Donkeys were brought to rural Australia as pack animals, as Western settlers began to make inroads in the outback.

Manda: Because you can brutalise donkeys a lot more than you can horses before they drop dead, basically, yes.

Judith: Yeah, that’s basically it. And then when mechanised transport came in and the donkeys weren’t needed, they were just set free. And donkeys live a long time. They do upwards of 40 years often. And so they were forming bands and communities and moving around and surviving and even thriving. So at Kachana Station, the donkeys showed up. And very quickly, Chris and his father observed that the donkeys were going places where the cattle wouldn’t go. They could handle rougher terrain. So they were bringing moisture and fertiliser to that area, and they were eating the vegetation that otherwise would have dried out during the dry season and become fire fodder. So the land where the donkeys were was healthier. Now, the government, however, said donkeys are not native, so they’re going to be using the resources that native animal wildlife would otherwise use, so we have to get rid of the donkeys. So Western Australia has been, and that’s a very large state geographically where Kachana is, they’re fairly determined to eradicate donkeys. So it’s been this ongoing process of trying to educate government officials so that they understand what the donkeys are doing for us. There are scientists that have been working with Kachana station that have found extraordinary things. One example is that they understand that donkeys dig wells, so they’re digging wells and bringing up water so that they have the water.

Manda: Wow! But also everything else has water. Hey, look, guys, we found water! Woo hoo!

Judith: Right! And they move brush around in a way that serves small marsupials, that creates favourable conditions for them. And many of these species are endangered. Then a scientist named Arianne Wallach talks about invisible megafauna; so it’s animals that are in the landscape but are not native, yet are having an impact on the landscape. She found that donkeys and other introduced megafauna…

Manda: Camels I think was the other one.

Judith: …Camels and I think Cape buffalo. That they are filling an ecological niche that has been void since the end of the late Pleistocene. So we know that Australia has very thin, kind of nutrient poor soil, and much of the Australian landscape is very vulnerable to fire. Well, that’s a reflection of the lack of megafauna in the landscape.

Manda: Right. Interesting. And I was reading a paper a couple of days ago saying 800,000 years ago, so roughly the Pleistocene end, humanity was down to 1280 breeding functional units. They’ve done this looking at DNA. It’s really interesting. They’ve looked at bottlenecks in DNA evolution and that there must, they suggest, have been an extraordinary climactic crisis at that point. We don’t necessarily know what it is, but people were not coping very well. And there’s been this colonial concept, patriarchal predatory capitalist concept, that obviously people hunted the megafauna out of existence because they could. Which isn’t necessarily untrue, but I think there’s an increasing suggestion that maybe they just died. At around the time there was this 1200 people total. We are all related to those 1200 people. Every single one of us goes back to one of those or two of those effectively. So that struck me as interesting. And I was reading Tyson Yunkaporta’s new book: Right Story, Wrong Story. Have you read it?

Judith: No.

Manda: It’s really, really interesting. And he says a number of very interesting things. But the one that came to mind while you were talking was he’s describing the making of a dugout canoe. And it’s a very clever book because in the Aboriginal way of speaking, time is not linear, but he’s trying to create it linear enough that we in the West can cope with it. And he’s talking about the adults finding the log and beginning to shape it into a canoe. And the children are playing games, jumping off a bend in the north bank of the river into the water, because today it is safe and tomorrow it won’t be.

Manda: And he just drops that in and leaves it. And then about 100 pages later on, he says, we the people of the right story, the Aboriginals, don’t have the Palaeolithic fight and flight response that you all speak of, because we know where the predators are, always. And I thought, I wonder how much of our narratives of how the world was, are making assumptions of our brains function like this, therefore their brains function like this. We have fight and flight, therefore they must have had fight and flight. We are scared of snakes, they must be scared of snakes. And actually they know where the predators are always. And I am putting that together with the Sami and with all around the world, where you’re talking about indigenous peoples and wondering how many of the ones, say the Sami or the native Australians or the native North Americans or South Americans, live in that world of verbs where everything is connected? And wouldn’t it be interesting to bring Tyson into the land, to see the dreaming of the land and see how the land is responding to the donkeys, or the camels, or the Cape buffalo? Because it may be that the land really welcomes them and that there is a narrative that is missing from our way of telling stories. Because our way is: X number of donkeys create this in the ecosystem, and this is either good or bad, depending on your viewpoint. And we either want to machine gun them from helicopters or we want to keep them going. But wouldn’t it be interesting to bring in Tyson and people like him who can talk to the land and and ask it what it thinks and give it a voice?

Judith: Yes. There was one quote I remember that I put in the book, from an Aboriginal elder, who rather than railing against the presence of the donkeys or they don’t belong here or we need to control them; he simply said, they belong to this land.

Manda: Yeah, yeah. But getting the politicians to take that on board is going to be hard. So since you wrote the book, is there movement on that at all?

Judith: There is more awareness. I know that there will soon be a lot of media in Australia about this.

Manda: There’s some stories being seeded out. Yes.

Judith: Yes. There are stories being seeded and recorded.

Manda: Excellent.

Judith: And it’s still in a stalemate. But it’s not one of those moments when there’s going to be a hearing on X date and the donkeys may have to go.

Manda: Be exterminated thereafter. Because there must be epigenetic change in the donkeys. There’s a group of ponies called the Carneddau, a little bit west of here, who are feral Welsh mountain ponies. They live on the side of Snowdon and a few years ago, when it still got cold in this country, it went down to, I think -35, and quite a lot of them died. But the ones that survived, because there’s quite a lot of people interested in them, had undergone epigenetic change in that span. In surviving, their DNA was actually different. And so I am also imagining that you know how donkeys, a lineage of donkeys, you’ll have great, great great grandparents of the foals that are being born now, that are in real time adapting to that landscape. And if somebody decides it’s fun to wipe them all out, and then somebody else ten years down the line realises that actually donkeys are quite good, you have to start that process all over again and get new acclimatised donkeys. And you can’t just kind of fly them in from Europe and go, hey, go on, enjoy and expect them all to survive. So treating that as a precious resource strikes me as being quite important. If somebody could do the epigenetics on the donkeys, that would be interesting.

Judith: Right. And that’s knowledge. And just how I spoke earlier about how there is knowledge in the forest.

Manda: Yes. And Daniel Firth Griffith is doing amazing things on his 400 acres in the Appalachians. He has families of cattle and he lets them roam and and then he’s getting intergenerational transgenerational and and descendant knowledge of that land that’s being bred into the cattle. You end up with a kind of landrace that has adapted to your land.

Judith: Right. And nutrition. Because animals know what their bodies need, but if humans are controlling what they eat, if they’re feeding them grain and hay and all of that, then they lose that knowledge.

Manda: Yes. And that’s when they eat things that are poisonous. Because in the wild, animals are not wandering around killing themselves, eating the wrong things. And it’s not because they’re not there. It’s because they know what to eat, when to eat it. The ivy is safe at this time of year and not safe at that time of year. But if your horse is starving and the only green thing in sight is some ivy, it’s going to eat it and then you’re going to be a bit sad. Oh gosh, there are so many things we could talk about here. You talked before we came online. You said you’d been to a book launch in New York, and that sounded really exciting. Tell us a little bit about the book and how you came to be involved in it. And tell us a bit about what the launch was like, because that sounded lovely.

Judith: So this is a book edited and written by, I said edited because there are many contributors, by Ayana Elizabeth Johnson, who is a marine biologist, a professor and a climate activist. And the book is called What If We Get It Right?

Manda: I love that title.

Judith: So it’s interviews with 20 people who she describes as her teachers.

Manda: Of whom you are one.

Judith: I am one of them.

Manda: Oh, fantastic. Well done that woman.

Judith: Thank you. And it was really exciting. I have to say, I’m still kind of buzzing from it. Because it wasn’t your typical book launch and it wasn’t your typical kind of publicity discussion of a climate book. What she did was put together a climate variety show and brought humour and fun and music! And yes, there was a magician, into this.

Manda: And was the magician doing climate things. Was he taking I don’t little baby mountains and making the rain fall on them?

Judith: So it was she.

Manda: Oh sorry. Assumption on my part.

Judith: And what she was doing. Well, first of all, she was saying that what we do is magic. You know, bringing climate solutions to the fore and really grappling with climate solutions. So she was doing magic and showing how we are a community, that we can read each other’s minds without knowing that we could. And she could read our minds and all of that. The magician did something very interesting. She had three rings and showed how we don’t think that they can be interconnected, but they can be interconnected. And she did that with her magician toolkit.

Manda: Interesting.

Judith: But then it came clear that those three circles created a Venn diagram. And Venn diagrams are one of Ayana Elizabeth Johnson’s favourite things. And she she often uses this in a climate sense, that what is your role in climate? So you have interlocking circles: what am I good at? What needs to be done? And what gives me joy? And where those three meet is your climate superpower and what you can do. But the dinner, there was a dinner for contributors the evening before, and I was stunned that people I was meeting were comedians. So I had to think, okay, how does this work? And there are comedians working on climate to engage people, to start people thinking in creative ways, to bring in the element of surprise. And it was incredibly high spirited, this climate variety show. They had contests. They had a woman who was talking about the sex lives of animals while she was using a hula hoop.

Manda: Wow!

Judith: And the show Ted Lasso, the character and the writer of that show, Jason Sudeikis, he was the co-host with Ayana.

Manda: She got some really sparkly people. Fantastic. Policymakers? Were there any policymakers in the room, do you think?

Judith: Actually, yes. One woman is a special assistant to the US president on climate.

Manda: Okay. Doesn’t get much higher up the tree than that.

Judith: And one woman is an indigenous, Native American liaison to the Kamala Harris campaign.

Manda: Fantastic.

Judith: Yeah. There were all kinds of different roles that people play. One woman works at NASA. So there were farmers. There were writers. There were policymakers and scientists, researchers.

Manda: As well as comedians and magicians and presumably singers. Brilliant.

Judith: Yes. And some of those professors and scientists were very funny!

Manda: Right. Turned out to be multi-talented. Yes. Right. Oh, that’s so good. That’s so heartening. Thank you. That’s really cheered me up. So we’re almost at the end of our time, but I’m wondering, where are you going next? Because you’re so prolific. You write so much, and you end up going around the world to conferences in lots of different places and then visiting people who are doing amazing projects. What next will we see from you?

Judith: Well, I can say that one thing I’ve been doing more of is bringing that work home. So getting involved in what’s happening here in Vermont. So for example, there is a solar array that involves cutting more than 40 acres of healthy, intact forest. So getting involved.

Manda: No! To put up solar panels. Oh, God.

Judith: So one concept that came out of that conference in Munich on the biotic pump that I’m thinking a lot about now, is climate sensitivity. And feeling to bring that understanding to the forefront. What climate sensitivity is, is the amount of warming per increase in CO2 per increase in the greenhouse gas impact, which seems to me really important because that’s what effect is actually happening. So where that becomes meaningful is let’s say that you have a place that’s full of roads and sidewalks and parking lots. Concrete world. Per rise in CO2, that place is going to get very hot because it’s holding the heat. Because of what happens when sunlight hits the ground. It creates heat.

Manda: Because there’s no transpiration. There is no biotic pump.

Judith: Exactly right. Whereas if you have a healthy forest next to a healthy grassland, those natural systems are creating a buffer for that heat, because there is transpiration, because there is the production of clouds, which requires natural processes driven by plants. So it seems to me that restoring the ecosystems, the health of the ecosystems is work that we can do that will make a difference, that creates a buffer.

Manda: And increases resilience, doesn’t it?

Judith: Right. What she said is it’s harder to heat up that landscape when you have healthy vegetation.

Manda: And does it work even if you have, say, grass roofs on the buildings and maybe growing things up the walls of the buildings, and then you take some of your parking lots and shade them over and put grass there. Is that even a worthwhile strategy?

Judith: Absolutely. But that requires more resources. And most municipalities haven’t chosen to put resources into that. And private citizens haven’t been called to do so either. But we can.

Manda: And over here we’d have planning laws that would go, oh, no, you can’t do that. It doesn’t look right. We’re in the middle of the sixth mass extinction, and you’re worried about what style the windows are. And I’m also thinking, presumably there’s a trade off with dead trees are worth more than live trees. We cut down the forest, we get some money, and then we can put up our solar park, and we get some more money. Which is not grand, but if you need money and you’re a cash strapped city, county, district council, then you do that. Is there an option to get a group of people together to go, no, let’s have the solar panels on the roof of every public building instead of cutting down the forest and putting it there. Is that a thing?

Judith: Well, what has been a thing is that with all the incentives for green energy, big corporations that are basically holding companies of holding companies, and if you trace it back to where it begins, it’s often fossil fuel companies. They are investing for the carbon credits and they’re driving this. So really exploiting the good intentions of the state.

Manda: Yeah. So we’re looping back to the beginning, of everybody’s focussed on the carbon, like your dog was focussed on the scent and there’s money to be made in it. And then everybody ticks their inner box of I was feeling guilty, but I’ve done my bit and everything’s fine. And so the system can carry on because now it’s all going to be fixed. And nobody understands complexity as a thing and this is not fixing it. Right. Oh, I hope your narrative of what happens if we get it right is spread. So are you holding public meetings and talking to people or talking to people in the supermarket? What are you doing to change things where you live? And if the answer is nothing, that’s fine. I’m just assuming you’re going to be doing something.

Judith: Oh, um, doing as much communicating as I can at public meetings and in the newspaper and on radio, and working with other community activists who are learning from this process. Because when it began, most of us only heard that solar energy will save us.

Manda: Yeah, we’ll need all these electric vehicles urgently, so we have to have lots of solar.

Judith: And solar energy has many, many benefits, but it’s not going to save us if we destroy the ecosystems to put up solar. So I’m very involved in that. And then I’m involved on my own land, putting in plants to support native pollinators. Right. Because that’s something that anybody can do. I began The Reindeer Chronicles by saying that people always ask me what they can do, and I always say, start where you are. So I chose I’m choosing to take my own medicine and start where I am, and it’s right outside the window where I am, where I’ve planted a lot of native plants.

Manda: Excellent. And so two questions, very quickly before we end. Are you finding you’re having to plant non-native plants because the native ones are being assaulted by the changing climate? And is it working? Because we’ve had a year when the insect numbers have plummeted. It’s absolutely terrifying. Are you seeing that too?

Judith: Not Plummeting. We have a lot of wonderful insects, which I enjoy, and I know that by putting in the plants, the insects do show up. So we have that capacity here in New England, which I don’t take for granted.

Manda: Yeah. Because there’s lots of places in the world that you’ve been to where that’s much, much harder. Judith, thank you. This has been really amazing. Is there anything in closing that you wanted to say that we haven’t covered yet?

Judith: No, I don’t think so. Just inviting people to engage with nature and understand that nature is working, and it’s not just looking pretty.

Manda: Yeah. And if we allow it, nature heals with remarkable speed. We just have to to kind of stop bashing it on the head with a hammer every single day. Thank you. And I have your website already in the show notes. I will find the other website and I’ll link to all of your books. Are there any places I might not have found that I should go looking for?

Judith: It seems to me like you’ve done some pretty good excavation work.

Manda: Well, I hope so. I will send you the show notes and you can check. And if there’s anything that I’ve missed, people, it will be there by the time you get this. Great. Grand. We’re there. Thank you so much for your time and for everything that you’re doing. Genuinely, your books are amongst the most inspiring that I’ve read, so I’m very grateful.

Judith: Well, thank you so much for the opportunity to chat.

Manda: Thank you. We’ll do it another time. But for now, thank you for coming on to the Accidental Gods podcast.

Manda: And there we go. That’s it for another week. Enormous thanks to Judith for giving her time and the depth of her understanding and her humour, and her capacity for enthusiasm and the understanding that everything is complex. Genuinely, The Reindeer Chronicles is one of the most inspiring, thought provoking books that I have encountered in a long time. It’s beautifully written and genuinely a lot of the stories in it left me feeling that there is hope for the world, at a time when hope can sometimes seem in quite short supply. I have put links both of Judith’s websites and to the Biotic Regulation Conference and Judith’s papers there, and anything else that I thought might be useful. They’re all in the show notes. Please go and find them. Click on them. Go and explore this world. And if part of it brings you to that place where your heart’s greatest joy meets the world’s greatest need, and both intersect with what you’re good at, then please leap in. Do what you can to hold conversations with people so that they understand it’s not all about the carbon. Cutting down old growth forests to put up solar farms is not a useful thing to do. And there are better ways, but the better ways are going to involve us sitting down and talking with each other and healing the rifts within and between us, as well as the rifts between us and the rest of the living web of life.

Manda: So that’s it for this week. We’ll be back next week with another conversation. I think the next one is with Leanne Hosier and perhaps someone else from Watershed Investigations. So we’re going to be staying on a watery theme for a little while longer. And in the meantime, enormous thanks to Caro C for the music at the Head and Foot. To Alan Lowles of Airtight Studios for the production. To Lou Mayor for the video, Anne Thomas for the transcripts and Faith Tilleray for looking after everything behind the scenes. And as ever, an enormous thanks to you for giving us your attention and your time. For caring enough to listen, and for sharing the podcast with other people who might get it and who want to be more deeply informed. So if you know anybody who wants stories of reindeers and donkeys and wonderful things happening around the world, and how we can come to understand the nature of water and how important it is, then please do send them this link. And that’s it for now. See you next week. Thank you and goodbye.

You may also like these recent podcasts

Dance of the Spiritual Warrior: Balancing Love and Power with Jamie Bristow

What does it mean to (re)orient our entire culture around the power of love? To answer this, we have to understand the nature of love and of power and how both of these have many meanings in our culture, some of them essential to moving forward – and some of them so toxic they turn the entire concept into a poisoned cue.

The Magic of Darkness: learning to love life in the night with author Leigh Ann Henion

Do you love the dark? Do you yearn for sunset and the amber glow of a fire with the night growing deeper, more inspiring all around you? There’s a world out there of sheer, unadulterated magic that is only revealed when we put aside the lights and the phones and the torches and step out into the night – as this week’s guest has done.

Starting in the Ruins: Of Lions and Games with Crypto-Advocate and Changemaker Andrea Leiter

This week’s guest, Andrea Leiter is one of those polymaths who brings not just breadth, but astonishing depth to the work of bridging the worlds of technology, biodiversity and international law bringing them together in service of a new way of being built from the ruins of collapse.

Walking the wild, mythic Edge of Being with visionary elder and soul initiator Bill Plotkin

What is the true vow of your life, the one it would kill you to break? This phrase comes from the poem ‘All The True Vows’ by David Whyte, but there can be no better introduction to this week’s guest, who knows how to help people – ordinary, every-day people from our culture – build true, heart-felt connections with the web of life such that we come to know our unique gift to the world.

STAY IN TOUCH

For a regular supply of ideas about humanity's next evolutionary step, insights into the thinking behind some of the podcasts, early updates on the guests we'll be having on the show - AND a free Water visualisation that will guide you through a deep immersion in water connection...sign up here.

(NB: This is a free newsletter - it's not joining up to the Membership! That's a nice, subtle pink button on the 'Join Us' page...)