#313 The Magic of Darkness: learning to love life in the night with author Leigh Ann Henion

Do you love the dark? Do you yearn for sunset and the amber glow of a fire with the night growing deeper, more inspiring all around you? Most of us don’t – though our ancestors through all of history have lived by firelight, moonlight, starlight… until the modern era of light at the flick of a switch. But there’s a world out there of sheer, unadulterated magic that is only revealed when we put aside the lights and the phones and the torches and step out into the night – as this week’s guest has done.

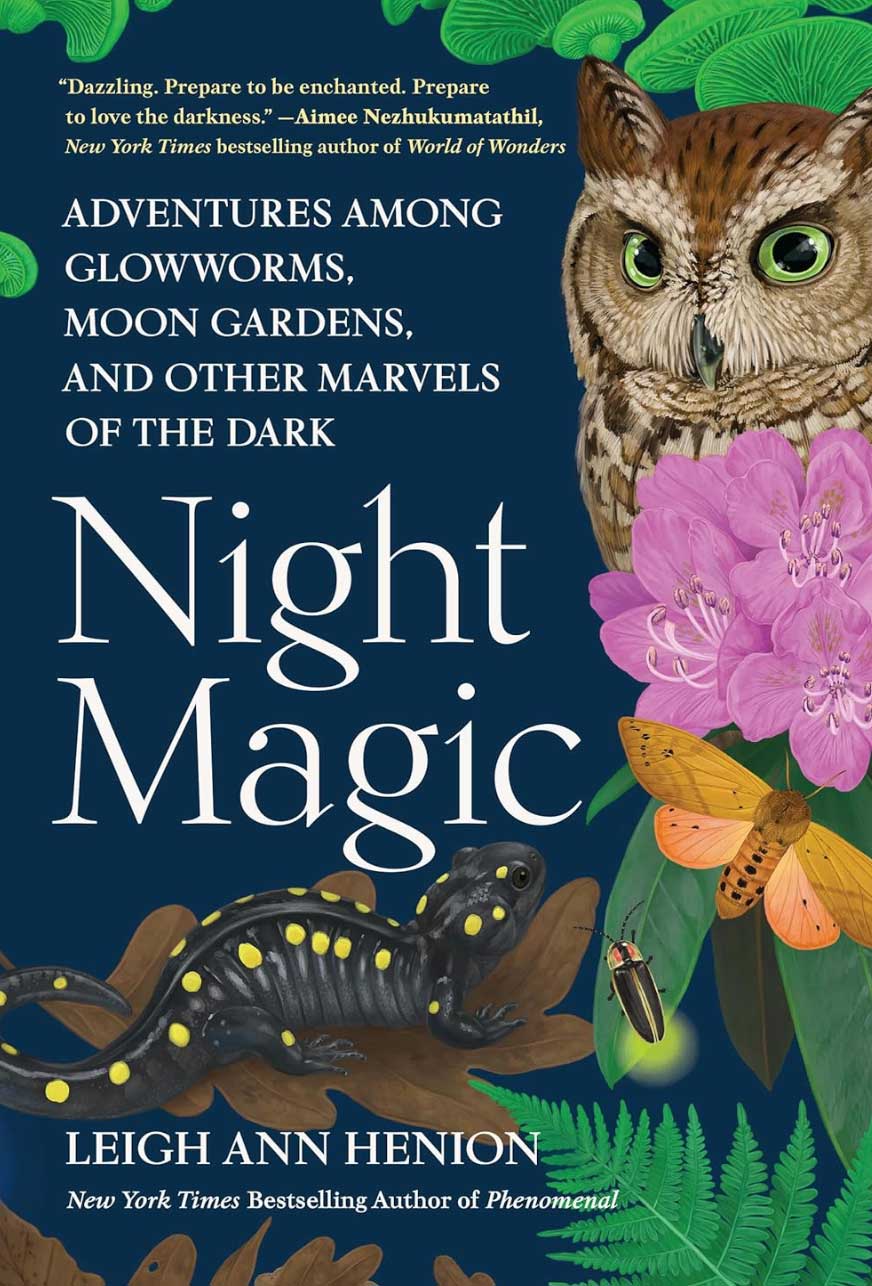

Leigh Ann Henion is the New York Times bestselling author of Night Magic: Adventures Among Glowworms, Moon Gardens, and Other Marvels of the Dark and Phenomenal: A Hesitant Adventurer’s Search for Wonder in the Natural World. Her writing has appeared in Smithsonian, National Geographic, The Washington Post, Backpacker, The American Scholar, and a variety of other publications. She is a former Alicia Patterson Fellow, and her work has been supported by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation. Henion lives in Boone, North Carolina.

Wall Street Journal says of this book. “Lovely…truly inspired…and very clever…An appreciation of nature’s nocturnal organisms can help us reset our relationship with the night…That’s the gift of Night Magic: It may make you think differently about the night.”

Episode #313

LINKS

What we offer

If you’d like to join the next Open Gathering offered by our Accidental Gods Programme it’s Dreaming Your Year Awake (you don’t have to be a member) on Sunday 4th January 2026 from 16:00 – 20:00 GMT – details are here

If you’d like to join us at Accidental Gods, we offer a membership (with a 2 week trial period for only £1) where we endeavour to help you to connect fully with the living web of life (and you can come to the Open Gatherings for half the normal price!)

If you’d like to train more deeply in the contemporary shamanic work at Dreaming Awake, you’ll find us here.

If you’d like to explore the recordings from our last Thrutopia Writing Masterclass, the details are here.

In Conversation

Manda: Hey people, welcome to Accidental Gods. To the podcast where we still believe that another world is possible and that if we all work together, there is still time to lay the foundations for a future that we would be proud to leave to the generations that come after us. I’m Manda Scott, your host and fellow traveller in this journey into possibility. And this week we’re exploring the dark, the night, the time after all the lights have gone out. Because most of us don’t love the dark. Most of us don’t yearn for sunset and the amber glow of a fire, with the night growing deeper and more inspiring all around us. Our ancestors, through all of history, lived through their nights by firelight and moonlight and starlight, until the modern era of light at the flick of a switch. And most of us don’t know of this night, this dark, of the life out there. Of the world of sheer, unadulterated magic that is only and can only be revealed when we put aside the lights and the phones and the torches and dare to step out into the night as this week’s guest has done. Leigh Ann Henion is The New York Times best selling author of Night Magic, which has the subtitle Adventures among Glow-worms, Moon Gardens and Other Marvels of the Dark. Before this, she wrote Phenomenal; A Hesitant Adventurer’s Search For Wonder in the Natural World. Today we are going to be talking about Night Magic, of which the Wall Street Journal says that it is lovely and truly inspired and very clever. An appreciation of nature’s nocturnal organisms can help us reset our relationship with the night. And this is the gift of night magic. It may make you think differently about the night. And it certainly made me think differently about the night, as well as teaching me an enormous amount of things that I rather wish I’d known before and am really glad that I know now.

Manda: This is a genuinely beautiful book in all senses. Leigh Ann’s Wordcraft is genuinely delightful, but in amongst all of the beauty of the prose, there’s a sense of vulnerability, of courage, of opening to possibility. Of yearning to learn and then the absolute awe and wonder and gratitude that arises when we begin to connect with the deeper parts of ourselves that can only be revealed in the dark. For me, this is a genuinely thrutopian book. It sets us on a path to different being, and it’s not hard for us to follow the steps; we just switch off the lights. But as Leigh Ann shows in the book, and as we uncover in the conversation you’re about to hear, it does take a lot of courage to do this. But it’s also deeply worth it. I have a new puppy, and so there are moments when the puppy is dreaming, and I chose not to wake her up or to rerecord after she’d finished. There’s also a cat on the new wall structure that keeps the cat out of reach of the puppy. And he started snoring partway through. So you may hear cat snores and puppy dreams. And along with that, hear the depth and wonder and majesty of all that is alive in the night. So here we go. People of the podcast, please do welcome Leigh Ann Henion, author of Night Magic.

Manda: Leigh Ann Henion, welcome to the Accidental Gods podcast. How are you and where are you on this kind of misty November day?

Leigh Ann: I’m doing well. I’m in southern Appalachia, western North Carolina in the United States, and I am watching a light snowfall. So I have some snowflakes and they are truly dancing outside of my window this morning.

Manda: Goodness, I had no idea you had snow this early in the year. Well, happy snowfall. Thank you. So you have written an absolutely stunningly gorgeous book, which I genuinely loved from pretty much the first page. Well, actually from the first page. And there’s a paragraph towards the end, page 234 that we both really liked. So would you like to read us that? And then we will explore the depth and breadth of your book.

Leigh Ann: Sure.

Manda: Over to you.

Leigh Ann: We fumble and fail to find words to explain the way our bodies are reading the signals these flowers are emitting. I close my eyes, inhale deeply, just as Foxfire showed me that I have better night vision than I imagined, I can feel these night blooming flowers introducing me to my sense of smell as one that I have thus far mostly ignored as important. Every waft feels like gratitude for the sense of smell I’ve taken for granted. Maybe as a species, most humans have.

Manda: Yes, and I’m sure we have. And amongst the many, many things I learned from your books is that our sense of smell becomes most sharp around dusk, when the night blooming flowers that you were discussing in that paragraph, the nicotiniana, begin to unfold. And I discovered that some of our sense of smell is as sharp as our dogs. I had thought dogs were five, six, seven orders of magnitude better at scenting than we were, but they’re just better at scenting other things than us. So this is a book full of things that I didn’t know. But most of all, of all the things that really struck me, was your capacity, your willingness to take risks. Your willingness to be vulnerable, to walk in total darkness and trust the person in front of you that they’re not going to lead you into a bear trap, or over the edge of a cliff, or into anything inescapable. And your rediscovery of the embodied skills and senses that our species has had for the whole of our evolution, until very, very recently. My relationship with electric power and light in particular, has revolutionised since reading your book, and I thought I was quite switched on to these things. But now I’m much more switched on. So before we go into more detail about how you came to write it and more of the the visual experiences that are near the start of the book, tell us a little bit more about the sense and the rediscovering your sense of smell that occurred when you went to your friend Amy’s garden.

Leigh Ann: So the book is really my personal quest to appreciate natural darkness in an age of increasing artificial light. And starting out I knew that this was going to be about meeting various nocturnal species. I knew that I was going to learn a lot. But every page, every bit of this book is me not even being able to wait until the book came out. You know, I started texting friends, calling people, like, did you know this? You know, ultimately, it really was a journey that not only introduced me to a world that I thought I knew, because I also thought that I was in tune. I thought that I was attuned to the landscape directly around me, only to discover that I really only knew half of it. So there was this entire half of my home, half of my immediate surroundings that I was acquainted with. So night was this entirely new country to be explored. And one of the really amazing things that did happen, was that I realised not only was I exploring outward, I was exploring inward, because ultimately there were all of these things about myself as a human animal that I didn’t know. The fact that our sense of smell is also part of our circadian rhythm.

Leigh Ann: We think of circadian rhythm as being attached to sleep. A lot of people understand that blue light, disturbing, can affect sleep. But I mean, who would have ever, it’s just shocking to me that my sense of smell was also connected to this. And a lot of people, if you ask, how long do you think it takes for your night vision to ripen? You know, people will generally say, and I’ve been in a lot of groups and people generally say 20 to 30 minutes. And it is true that we gain most of our night vision early on in the first 20 or 30 minutes. But I couldn’t believe when I learned that actually we gain night vision incrementally for hours. So I love being able to tell people. If you’ve never pointedly set out to experience your own night vision, if you have never spent waking hours in the dark, not looking at your phone, protecting yourself from points of artificial light, then you have powers you don’t even know about. So it’s really exciting, right? To discover not only the world around me, but also these latent kind of abilities as a human animal that I had and that when I tapped into were really wondrous in themselves.

Manda: Yes. And also, it sounded like, through the book, you discovered a lot of people in your area who were similarly inspired and on their own journeys. Like your friend Amy, who was planting, as I understand it, she was planting with biodiversity in mind, but she hadn’t thought about planting night blooming flowers specifically. It just turned out that she happened to have planted them because she was trying to grow the kinds of things that were grown by the people who had built her house back in 1892. And a lot of them turned out to be night blooming flowers that then drew in all these amazing night creatures that I don’t even know if half of them exist in the UK, but it makes me want to visit the US. I’m not going to because it’s not a safe space at the moment, but you know, when you guys get it back to it being safe, I want to see the Hawkmoths and these great big moths that you have there.

Leigh Ann: Well, I focussed on my home region because it’s the place I know best. But I wanted to model that this is my home…

Manda: What’s in your home?

Leigh Ann: Yes. Like I want this to be a model of, like, this is my home, this is my journey, but like where are you? Because wherever you are on this planet, after dusk, there is an entirely new world to be explored. And so truly, you know, you do have some glow worms, different than what we call glow worms in my area. Fantastic moths in the UK. I mean, you have a different biodiversity. Darkness is really a connector, but, you know, biodiversity is really pretty specific to place, which is really thrilling. You can experience what I experienced, but really just kind of as hopefully inspiration and an invitation to get to know your own space in the dark. Yeah.

Manda: Yes. Wherever you are in the world, there will be amazing things out there.

Leigh Ann: Well, I do love the story of my friend Amy. You know, she planted this garden and she really cares about history and doing things correctly. If she gets a doorknob, she wants to have a doorknob that’s period appropriate for her home. She actually has sheep, she has livestock that are the same as the livestock…

Manda: Period appropriate livestock.

Leigh Ann: Yes, she has period appropriate livestock. And so when she planted this particular area of her garden, she was planting period appropriate. I mean, she read historic diaries, she really went deep to try to do this. And when she discovered that she had unintentionally planted this moon garden, it was pretty thrilling. Because the inhabitants of her house, the early inhabitants, were pre electricity. So they had planted this garden as a place to be enjoyed in the evening. It was their form of entertainment. So ultimately it became our entertainment. And there was this moment, truly, where I can’t wait to publish, and I have to tell everybody all these things. And I told her about Hawkmoths, which are these hawk moths that are the size of hummingbirds. They’re extremely large moths. And she went out into her garden after dusk and you know, it’s a little hard to see, she’d never really spent time out there at that time of night. And she saw one almost immediately, you know, and she’s like, oh my gosh. She was almost in tears. And I’m like, what? You’re so emotional. And she said, because as soon as I went looking, it was there! And it had been there all along. Which is kind of how I felt throughout the book, because once I invited darkness into my life, once I sought out these experiences with nocturnal creatures, you know, I realised that the wonder that I had been seeking had been there all along. You know, an example of that is I’ve always wanted to go to New Zealand to see their glow-worms. You know, these famous neon blue glow worms. I was willing to travel around the world to see these glow worms, only to discover while writing Night Magic and researching Night Magic, that neon blue glow worms live in Southern Appalachia!

Leigh Ann: They live in Southern Appalachia, and very little is known about them. In part just because we don’t get out in complete darkness, we don’t allow our night vision to ripen. And spoiler alert, I not only find these blue glow worms in great concentrations, you know, just one town over; I ended up finding them in my own neighbourhood, on a road that I have driven with my headlights on at night for 20 years. But never before had I walked this path in total darkness with eyes adjusted, looking, you know, just seeing what I might be able to see on the forest floor or on this road embankment. I mean in daylight this is a nondescript ditch with road embankment, and at night it’s just spangled with these neon blue stars. And they were there all along, but I just couldn’t see them. So over and over this happened. So just this concept of discovery is right where you are. It’s really exciting.

Manda: Yeah. And you kept meeting people who had discovered new species in your area, in the places where you live, just by really going out at night with exactly as you said, those night adjusted eyes. It was glorious. So let’s rewind back to the beginning, because not everybody decides that what they want to do is write a book about what it’s like to be free of artificial light. How did you switch on to this?

Leigh Ann: Sure. So a few years ago, I have an editor that I’ve worked with for many years, a magazine editor, and he was working on a travel issue, and he was looking for travel writers that were going to write about travel close to home. And so there is a place in Great Smoky Mountains National Park and it’s a few hours from where I live. And famously, this national park is famous for a species of fireflies known as synchronous fireflies. So tens of thousands of people attempt to attend this event, to see these fireflies, to witness this phenomenon. Now, before I went, I thought that synchronous fireflies meant that they all flashed on and flashed off at the same time. Kind of because I think, you know, we live in the electrified world, it’s like lights on, lights off, lights on we wake up, lights off we go to sleep.

Manda: And synchronous sounds like that. It sounds like they’re all in synchrony. And that’s what a lot of our lights do. You know, disco lights all going on-off, on-off, on-off, and you think that’s what it’s going to be, but it’s not.

Leigh Ann: But it’s not. So I went and it’s like a delicately beautiful phenomenon. You see a little twinkling on the forest floor, and then all of a sudden you see these lights just whoosh across the forest floor, and then they go in another direction and they woosh back. And it truly is like a living version of the Northern Lights, you know, right just above the ground. And what actually happens is these fireflies communicate with the firefly next to them. So they see this flash and it’s a cue for the next firefly to flash. So it’s really a communal light show. And it was fantastic. It was gorgeous. And before I went seeking these fireflies, I never knew that there are hundreds and hundreds of firefly species, and each species actually has a flash that is as unique as a fingerprint. And where you see a firefly, you usually have multiple species, which I then discovered blue ghost fireflies, which are these fireflies that are neon blue and they stay lit for 60 seconds at a time. So when you’re walking in the woods and you’re surrounded by these fireflies, you are surrounded by these unblinking, tiny blue orbs of light. And it is truly like walking among fairies. So I had no idea that all of these magnificent things existed in my home region. And so I learned a lot about fireflies, and I learned about how light pollution negatively affects pretty much every part of their life cycle. And again, spoiler alert, pretty much every living being on Earth is negatively disturbed, disrupted by artificial light. But so in this process, I also realised that I had not really spent time in complete darkness exploring the world around me. You know, without my phone, without any flashlights, with any torches.

Leigh Ann: So it was a really powerful experience. And I started to recognise, especially, you know, I just have a life of so many screens, you know, phone, computer, television, so many screens. So in that moment, I began to realise how restorative it was to spend time in the dark. And I also was introduced to the concept of darkness as having the power to reveal things. Because I wouldn’t have been able to witness that synchronous fireflies event, I wouldn’t have been able to walk among the Blue Ghost fireflies if it had been a lit environment. So we often are told darkness is a dearth, darkness equals death, darkness is a void. So to start recognising darkness as having this power to reveal. You know, if I say I’m going to leave you in the dark, that’s like I’m going to leave you in ignorance. But to recognise Darkness has wisdom, darkness has the power to reveal. That was incredibly moving. And so I published this magazine article. And what really was amazing is that I found strangers went to the trouble to find me, find my email, they were sending me messages on social media, they were contacting me to say, hey, I loved that story about fireflies and it has inspired me to turn my porch light off more often. And that was just amazing to me. It blew my mind. Because it’s so hard to change a habit. It’s so difficult to inspire a direct action. And so this story had inspired people to take direct action, to physically turn a switch off, in ways that really benefited not only the wildlife around them, but themselves. And restored habitat pretty much immediately. Because darkness is habitat and we don’t often think of it in those terms, but it is. And so after this happened, I learned so much from fireflies, so what would I learn from spending time with owls and salamanders and moths and bats and glow worms and foxfire? Foxfire is bioluminescent fungi.

Manda: All the things that live in the dark.

Leigh Ann: Yeah. Intimate encounters with all of these things. You know, spending time in moon gardens. Yeah.

Manda: And that is the book. And and what you learn, it feels to me as if the the outer journeys were amazing. And the people that you meet, all these people who are so enthusiastic. So you went to Appaloosa, which is all about moths. You met the bat lady who had bats in her hair and then learned all about bats. What I really loved, of many of the things I loved about this, was you managed to get scientific data in there, but it’s also the personal journey and the journeys of the people around you. I’m remembering a young girl who’s on one of those night walks where the guy is walking backwards in the dark, which is just obviously a really cool skill. And you all then feel safer about walking forwards. And there’s this lass who looks like she basically just wants to go back to her phone, but you hand her, I think a fungus. It might even be Foxfire. And you are able to evoke the awe that she feels. And it seems to me that, exactly as you say, if we’re going to create that thrutopian future where we’re all more connected to the web of life, you don’t do it by telling people they need to, you do it by helping people experience it. And there isn’t anywhere in your book where you go, this is the way forward, we need to be doing this.

Manda: But you evoke awe and wonder on almost every page. So I have switched off more lights. I sat down in the stable, it was pouring with rain. I’ve got a puppy that doesn’t like the rain and I took her out to one of the stables and I just sat in the dark while she discovered some horse poo and ate it, because that’s what puppies do. But I was relying on sound to know where she was and what she was doing and listening to the rain. And discovering that the ponies don’t like being in their stables, even though it’s sheeting down with rain, they’d rather be standing under a tree up the hill. All of the things that I wouldn’t otherwise have known. And I’ve sat through the night as night sits often enough to think that I really know this stuff. And I really found depth in your book of I need to sit out more. I need to spend more time out in the dark. And I’m wondering, I’d like to go back to more of the story soon, but since the book has come out, because it’s been out a year now, have you had more people contacting you on social media, and more people switching off some of the super bright lights. Is that a thing?

Leigh Ann: Yes, absolutely. And actually, on that positive note, I’m so thrilled that that was what you took away from the book. Because I really tried not to focus on what light pollution takes away, but rather on what darkness offers. Because we really just do not have many dark positive stories. You know, pretty much everything in popular culture is encouraging us to banish darkness as soon as we encounter it. But I love those moments that you were sitting and experiencing. I do think there’s kind of a forced mindfulness to being in the dark. Senses kind of coming alive in the dark when you’re less able to focus on vision as a dominant sense. You know, you start hearing things and feeling things and sensing things differently. And also even walking in the dark. Talking about my guide who walked backwards, I think maybe as a confidence booster as we were beginning to walk in total darkness, but when you’re walking in the dark, you have to do it tentatively. Nothing can be taken for granted. And so I think that that’s a real gift of darkness. And in terms of people reaching out, I have a neighbour who, while I was working on the book, she was like, oh, I’m so excited that you’re writing about this, because I have a neighbour who’s just put up a light that’s shining directly into the bedroom. And she’s like, I do not know how to talk to him about this.

Leigh Ann: So I said, okay, I’m working on this book, I want this to be a story that Kristen could just slip a copy of this book into his mailbox as an invitation rather than a wagging finger. And so I really tried to do that. And I actually told that story at a book event once, and I have people come up and they had a little stack of books and they were like, okay, can you make this out to me? And they’re like, actually, could you just make this out “To Don, turn out the light”. And then I signed my name, but they didn’t sign their name, but it went into his mailbox. But I don’t think that people reached out to me after I wrote that very first story because I was talking about the the harm of light pollution. I think they they reached out because they got curious about what might be out there. And it’s such a powerful motivator.

Leigh Ann: Another great story, I had an event where a woman came and she had a giant stack of books, and I was like, this is amazing, you know, thanks so much for the support. Are you giving these as gifts? And actually, she was having a neighbourhood situation where her neighbours all had too many lights on. And she said, I’ve decided I’m going to give these all as as holiday gifts to my neighbourhood, and then I’m going to have a dark appreciation party so that we can all get together. And kind of slip in oh, I think maybe I heard this owl species or whatever, just to get people excited about what might be communally happening in the neighbourhood. And this is so powerful and so exciting. You know, how to approach people, rather than approach with a list of ailments or a list of complaints, to approach them as truly using the book, which I hoped would be an invitation, as an actual literal invitation. So those have been really exciting stories for me. And I think they do kind of build on those original reader messages.

Manda: Right. And your personal experiences and all of cognitive neuroscience that tells us that people respond best to having awe, wonder, curiosity, Gratitude evoked. Rather than the thing that’s going to guarantee you keep that light on, is your neighbour going “I want you to switch the light off”. And what you’re using is the best we have of cognitive neuroscience, which tells us that the way to evoke change is to give people awe and wonder and gratitude and curiosity and build all of those, rather than the absolute guaranteed way to get someone to keep their light on forever and probably make it brighter, is to say you have to turn that light off. And they’re not going to. It just doesn’t work like that. And it feels to me like this is something that crosses cultural divides. The cultural divides are so toxic at the moment, are being made toxic by people who, frankly, are profiting out of toxic cultural divides. But you’ve created something that it doesn’t matter where you are in any spectrum, if you see a hawk moth, you’re going to have that awe and wonder. If you see a blue ghost firefly for a whole minute, you’re going to feel that. If you smell the nicotiniana, you have that bodily experience. So there are two things; one is that Amy, who we talked about earlier, who planted the garden, is a university academic psychologist, I think. So I’m guessing she knows this, which was really exciting. And then someone called Simon I think if I remembered it right. And his local council had put back a streetlight that had been out for ages, thinking that everybody’s going to be happy. The streetlight is back and Simon organises petitions and everything to go, no, no, switch it off, it’s hurting the owls. You can’t have the streetlight, you’re blinding the owls. Get rid of it! And so then the local political establishment understands that blistering light everywhere is not necessarily what everybody wants, which also seems quite a useful thing. So tell us a bit about the owls, because that was gorgeous. Well, bits of it were gorgeous. And then it was quite heart rending.

Leigh Ann: So that’s actually night blooming tobacco. And tobacco, up until I’d had that experience I, you know, it’s a dried plant, associated with the pipes and cigarettes. And it’s truly like a dead, dried plant with a lot of negative health connotations.

Manda: Age 12 you were given a packet of cigarettes. Tell us a little bit about that, because that blew my mind.

Leigh Ann: So where I live in my area of the state, it’s famously, historically a tobacco growing region. So agriculturally a lot of tobacco has been grown. I’ve really lived in the tobacco country. And so to have tobacco turn from this dead dried plant with these negative associations into this glorious living plant that provides for pollinators and provides for other wildlife was really powerful. And Amy, yes, she talks all the time about those positive associations and how that how that shifts things. So in the book I was like, who would even believe this happened? I wanted to have a close encounter with an owl, responsibly, you know. And then, lo and behold, my friends end up with an entire family of nesting owls. These little owlets. And I get to spend time with them and observe them. And one of the things about that part of the book, that chapter, that part of my experience, that was really powerful for me was that recognition. So the story is, there’s a light that goes on in the neighbourhood. Owls are going to nest in this owl box, but when the light goes on, they flee.

Leigh Ann: And so they flee into my friend’s yard where they have a cavity in a tree, that they then find a natural nest. And it just creates a lot of neighbourhood drama, right? So ultimately, we don’t know exactly if that’s why they fled, but it’s pretty reasonable to think they were fleeing this light. They found a dark place in the tree cavity. And that whole chapter really, for me, was important in the sense that I really started to absorb how important a single tree can be as habitat. We need wilderness. We need these great swaths of land, but we also need those single trees, you know? So the single tree was a home for this owl family. A single tree can also be home to hundreds of bats. So that was really important for me, because also that led me to understand migrating songbirds absolutely depend on darkness as avenues of transportation. And so thinking about darkness, you know, we can’t turn a whole city dark. You know, we’re probably not going to influence all the elected officials to turn all the lights out.

Leigh Ann: But it’s kind of like with those fireflies and that concept of ‘light the candle next to you and together we can illuminate’; well, if that is true, then therefore we can snuff out the candle next to us and we can grow the darkness. Not a lot of positive connotations with that, but darkness is a gift and it has so many things to offer. The daylight world that we experience, the forest that we appreciate, the gardens that we love, all of those are made possible by night pollinators, which do a lot of heavy lifting that are often forgotten about and are disturbed by loss of the dark as habitat. So the more dark patches we can create, the more that darkness grows. And over time, this really is an environmental issue that can be addressed, and you can have an effect pretty much immediately. So that’s really hopeful I think. Pockets of darkness, they matter, just like that single tree matters. A dark yard, a dark neighbourhood, a dark town. It just grows.

Manda: Yeah. And it occurred to me, reading it, that if we were to create a world where we were an integral part of the web of life, we would create dark cities by default, and there would be little bits of light where you needed them and the AI would work out where a person is walking on their own and create light where they are. And we wouldn’t have to, by default, have cities drenched in light. We’ve done that because we didn’t know it was possible to do anything different, and we’ve done it because we didn’t know that it wasn’t necessarily a good thing. And you write in the book about the Kalahari, and the conversations that happen after dusk around the firelight, in the dark, are very different conversations. So in daylight it’s gossip and economics, and at night it’s the stories and the myths and the things that grow community. And the young people are walking off into the desert trying to find a signal on their phones, which seemed heartbreaking. But, you know, also, my heartbreak is colonial because I want indigenous people to remain wonderful so that I can project everything onto them. And they just want their phones to work and my phone works and the world is so complex at the moment. But say a little bit about your discovery of how people are different in the dark, because, again, we don’t give ourselves the dark to be different in.

Leigh Ann: Yeah. What you said actually just reminded me of something that I started thinking about when working on the book, and I still think about, because it applies in so many ways. We have the technology to address so many of our environmental challenges.

Manda: All of them, actually.

Leigh Ann: But we don’t have the stories that necessarily inspire and guide us to implement changes. And so I really dream that this book is in that sense, a story that can help fill that space. And I think that it really is something that applies in so many different ways. And so the story that you’ve just brought up about the the Kalahari, you know there’s really limited research on how artificial light has affected human thought and human behaviour. But we have hints and a little bit of research that indicates that in situations of artificial light we tend not to use imaginative thinking as much. We tend to go to logistics, you know, all of that. But there there was a long term study which tracked language. And so the language that was used in daylight often was about logistics. There were arguments, planning, things like that. But then at night and by low light or amber spectral lights, fireside, which you know, for millennia we have gathered around.

Manda: That’s all we had.

Leigh Ann: Yeah. So the language used was almost always more about reconciliation, sharing and storytelling. Sharing ancestral knowledge of place and things like that. So when you really start to think about that and again there’s limited research, but think about conversations that you have in fluorescent lit rooms versus conversations that you’ve had at fireside, you know, sitting around a campfire. And, you know, that’s situational, but thinking about the fact that perhaps the light spectra and the use of light was influencing that, is really kind of an interesting moment.. And so now a lot of our communication is while we are staring into blue light of our screen. So to consider that that might actually be affecting the way that we are thinking and communicating, and the language that we’re using. It’s really powerful. But all of that kind of indicates that darkness as this expansive space, where we can let our imaginations run wild, how that has led to human development of culture right across the globe.

Manda: Yes, all of it. Until about the last 100 years.

Leigh Ann: Yeah. And potentially how it has been changing rapidly in just the last few generations.

Manda: Yes. And sensing down into the next generations, you speak about your son Archer quite a lot. And he was 12 in the book and I’m guessing he must be 14, 15 now. And there’s a heartbreaking bit where you said he’s got homework that requires him to have ten tabs open on his computer, and there’s nothing in a book with pages. It’s all done on screen. I’ve got a friend who’s entire podcast is about alternative forms of education and we so badly need not to be giving kids homework that requires ten tabs open on the computer. And yet you take Archer out and introduce him to the Moon Gardens and the Hawkmoths and the Firefox and you bring red light into your home instead of blue light. Is he tending more towards going out in the dark? I mean, he’s adolescent now, life is very complicated, I’m sure. But where is he at?

Leigh Ann: He’s solidly a teenager now, so he’s really just wandering into the dark to, you know, teenage life. Um, but you know. Right. And when I did switch over those lights, because it really did take my entire journey for me to realise that it wasn’t just about the way that I was using lights outside of my house and how they were disturbing wildlife, but also about how I was using lights inside of my house and how they were affecting me. So when the sun goes down and the sky turns amber and red outside, the lights in my house turn amber and red. Not always in sync, but, you know, before bedtime. And I really have found it to be a really helpful and restful situation. My son Archer, when he was young, he’d say, oh, this makes our house look like a haunted house, because it is a little bit funny to have those red lights and things. I think that he was a great sport to go on some of those adventures with me. He’s a great sport, and I think that he does have a little bit of an awareness about it. It kind of creeps in every once in a while, just that awareness and understanding. As a parent, I just hope that as he gets older, he carries that with him and it will surface in different ways as he gets older. And I still mourn the fact that he rarely has books in school. Think about a computer, tapping on those keys, versus writing with a pencil and lead.

Manda: Yeah. And I could have read this on a PDF, but it’s not the same as turning the pages and having a physical book.

Leigh Ann: And to touch that. You know, this is pulp, this is paper, this is a tree. That’s complicated too. But at the same time, I do feel like there is an intimacy and a relationship that you have with the world when it is made tangible. So, yeah, I hope that some of those field trips help him remember the tangible world. Yeah.

Manda: How do you read actual books under red light? Because I am thinking of trying to do that here, but we both read in the evenings and I’m thinking, how are we going to read with red lights? How does that work?

Leigh Ann: I actually do, I actually read by red light. Sometimes I read before I go to sleep and I do read by red light. My optometrist has told me that’s fine as long as you have enough illumination, if the bulb is bright enough, it doesn’t necessarily matter what spectra of light it is.

Manda: Okay. The wavelength doesn’t matter.

Leigh Ann: Yeah. So the wavelength, I find it still to be really relaxing and helpful. And I’ve kind of gotten used to it. Yeah.

Manda: Yeah. Okay, I’m going to go for it, because another of the factoids in the book is that because we’re already on screens, the blue light, and I’m already really, really short sighted, but half the population of the Western world is going to be myopic by 2030 or 2050. I can’t remember which. Because we’re focusing on small type on blue screens.

Leigh Ann: Yeah. You can also get the reading lights that clip on the book.

Manda: Oh yes.

Leigh Ann: You can get Amber reading lights specifically, which I have those too. I use those sometimes and I always travel with those. And sometimes if I’m in a hotel room and the lights are just so intense, I end up using almost like a little candle sometimes at night to start winding down. Yeah.

Manda: Brilliant. Okay. We’ll go for that. So towards the end of the book, you learn to make fire. And again, the guy who taught you sounds like a really interesting person. And your experience of fire was itself so embodied. Can you talk us through that? We want people to read the book, so don’t tell us every single bit. But it felt like such a deeply visceral and primal experience. So please tell us more.

Leigh Ann: Yeah, well, looking back on it, it’s so funny that I even came up with this concept. But I spent so much time with these different species, the last species that I wanted to really address was humans. So how do you address the human relationship to darkness and the human relationship to artificial light? And so I decided to trace artificial light back to its beginnings, by making fire with sticks and my own hands and a bow drill. And it turned into such an empowering experience. But one of the really interesting things that came out of that for me was the concept that we turn the switch on, the light comes on, we don’t really think about when we turn a light on, something is being burned, you know, the energy exchange. So what was really interesting to me in that process was how much work I did to get that light. And I really was able to absorb the cost of the light. And also this concept that to make light, our ancestors had to know the nuance of all these species that they were living with, you know? So I had to learn that the innards of poplar bark are really good tinder. The different woods that would make a good spindle stick.

Leigh Ann: So I had to know my landscape in order to create this light. And so that was a really beautiful experience. And I started with fireflies, ended with humans and it took me this entire journey to recognise, you know, we marvel over fireflies and bioluminescent creatures because they can make light inside of their bodies. But I ultimately realised, if they could, they would marvel over us because we are the only animal species that can make light outside of our bodies. So we are the light makers and we are the fire tenders, and we are the ones that can step back light to re-acclimate and to invite darkness back into our natural cycles.

Manda: Yeah. And the building of the fire and then the tending of the fire. You didn’t just pour water on it or scatter it, you just fed it less and less and less until it went back to where it started. I thought it was so beautiful.

Leigh Ann: Yeah, he was so wonderful and he’s a very thoughtful person. He spent a lot of his life, I think, creating ceremony and tangible experiences to kind of help people absorb these things, which was just really wonderfully helpful.

Manda: Yeah. And everything we know of healed and whole human cultures is that all of life is ceremonial. All of life is a sacred gift to the gods. All of life is that sense of gratitude. And that paragraph you read at the top of the show, that gratitude welling out of us because the world is so amazing. And in every page of your book you evoke this. And so I’m wondering, you wrote it a couple of years ago. It takes a year. You’ve been around the country with you signing copies for people and them giving it out to their neighbourhood, which is great. But the journey that you went on, there’s moments in the book where you are hugely courageous and you’re exposing the vulnerability of yourself. Of how you have met all of the different things. You were afraid of bats, but you went to stay with bat people. And the learning to build fire was hugely empowering, but it was hard. You can tell by the writing that it was hard and you changed the lights in your house. And I’m guessing your whole neighbourhood is probably less lit than it was when you started. Where are you now in terms of your relationship to yourself and the web of life?

Leigh Ann: Well, I feel often in my life and I think this is true for a lot of people, I have to learn the same lesson over and over again, you know. And one of the really nice things about this has been an enduring sense of alliance with darkness. I still do get a little nervous if I go out by myself. Even if I’m just in my own neighbourhood, it’s a scary thing. It’s intimidating. But I really have forever altered my relationship with darkness. I am so much more comfortable in the dark now, after these experiences, after they’ve compounded, after I completed the project. And also, one of the things I love about it is that once the story goes out, it doesn’t belong to me. It belongs to so many different people who take it so many different places. And that’s been really thrilling to watch. But if you spend time getting to know the night world around you, I have found that I now recognise the voices of my animal neighbours.

Leigh Ann: You know, if I encounter a deer in the dark, it’s actually terrifying. They do this huff. But now I know they’re speaking to me. Now I know the rhythms of their lives through seasons and those seasons repeat. And so I don’t have to relearn those lessons every year, because I kind of follow along with their rhythms and their season. When I hear a screech owl, it’s longer background noise. I’m like, oh, there’s the screech owl. And I will say this, once I started to recognise the voices of these owls, I hear them everywhere. I’ll be at a friend’s house and I’m like, oh, you have a screech owl! And they’ll be like, oh, really? So then that’s exciting to be able to kind of introduce them as neighbours. So the enduring concept of darkness as a friend rather than a foe has really informed my life in ways that continue to be revealed. And I am incredibly grateful for that.

Manda: Right. So you’re still going out. Because there’s a part where you go out into your own yard and discover a whole lot of night blooming flowers that you didn’t know were there before. And you encounter the deer and after the first couple of nights, you and the deer kind of negotiate who’s going where, and it becomes a kind of a dance. So I was curious to know, are you still going out in the evenings? Are you still exploring the Moon Gardens? Has that become a pattern of your life?

Leigh Ann: Yes, it absolutely has.

Manda: Fantastic.

Leigh Ann: Actually, I really recently was at Amy’s house, because she said, oh, the garden’s stayed longer this season. So I went over to appreciate and enjoy that. And the primrose, these wildflowers that grow in ditches and all over the place and in daylight they just look like these puckered weeds that I just never noticed before, only to discover that I was surrounded by these night blooming flowers. They actually have a little latch that pops and you can watch this flower bloom like a time lapse video. In daylight you wouldn’t notice, but then at dusk it becomes this beautiful little flower. It’s like a little miniature orchid, you know, all over the place. And so I can never go back to seeing the world the way that I saw it before. Once you know that there are all of these secret gardens around, you can’t go back to not knowing the secret gardens are there. And so really, it enchants the every day, daylight and night, you know?

Manda: Yeah. Yeah, absolutely. And you can’t uncare. You’re not ever going to put big arc lights around your house. It’s just not going to be a thing. And John Young tells us that the average indigenous child by the age of 12, has made meaningful relationships with over 400 other species. And what I was reading through your book was you making meaningful relationships with glow-worms and fireflies and salamanders and bats and owls and everything in the night blooming gardens. And I could feel that ratcheting up. And the deer and then the dogs that came with you and so exactly as you said. Not only, I’m guessing, now you’ll be able to go to your neighbours Oh you’ve got screech owls, but you’ll know the different owls in your own neighbourhood. I would think you’ll know, oh, that’s the parent owls, and that’s the young owls, and you might even know individual ones. And that’s how we build the relationships with the web of life, and it was magical reading about it.

Leigh Ann: Oh, I’m so glad you had that experience. And moths. You know, moths are so incredibly biodiverse and gorgeous. You know, people love butterflies and forget about moths. But moths are beautiful and they’re such important pollinators. And I think that a lot of people don’t realise their beautiful wing patterns and colours and like what is going on with moths. So, you know, I say mothapalooza, which is just as fun as it sounds. But when I went to Mothapalooza, I don’t know if there’s been a time in my adult life where I have learned more in such a small little bit of time. Because the diversity was just so grand. Right. Yeah. And so I think a lot of times we talk about this in terms of children, you know, nature programs geared toward children. But there’s so much to be discovered right here. That it’s not too late to start ratcheting up. Yeah. It’s very exciting.

Manda: And it’s not too late to begin to undo some of the harm.

Leigh Ann: Yes, absolutely.

Manda: Which seems really important. Because you were saying about satellites. That there are so many satellites now that are acting as miniature moons, that they are beginning to impact other species. And yet everybody wants their cell phone to work. How do we get people to care enough that they just don’t keep throwing satellites up into the sky?

Leigh Ann: You know, a lot of times when we do talk about light pollution, we talk about how it blocks our view of the stars, which is absolutely true. But while I was working on the book, I started to think that we might actually be at a place where that’s a little too far off. There are good portions of the population that don’t have, even now, do not have that relationship to stars, because light pollution has gotten so intense. But I really also started to recognise it’s not only blocking our view of the stars, our connection to that celestial beauty. It’s also getting in the way of our knowing the world directly around us. I mean, truly, in our own yards and our own gardens and our own communities. Because there is this night world to know. And light prevents that knowledge from being absorbed in a lot of ways. So to think of darkness not as a dearth, not as a void, but as a cornucopia of life, as a realm of discovery that can really only be explored kind of on its own terms, I think is again, to bring it back, just like the most powerful way that I know to try to invite and inspire people to do that. To invite darkness closer. Yeah.

Manda: Which it does. Yeah. And I think it probably helps also to know that various studies, in China and the rest of the world, that increased exposure to blue light not only increases depression, which I think is obvious because you don’t sleep as well and you’re going to get more depressed, but it also increases the propensity to diabetes. It just changes the whole of our physiology. Because for the entirety of human evolution, we had firelight and moonlight and starlight, and then we knew the dark. I think the love of your book is that coming to realise that the dark is a whole world in and of itself, and our ancestors must have known it intimately.

Leigh Ann: Yeah. The darkness is part of our natural habitat, too. It is part of our natural cycle, right? It aids us. Again, this concept of darkness as friend rather than foe. I mean, it is absolutely countercultural and it is a fundament to thriving on earth, you know.

Manda: Mhm. And so in terms of the feedback you’ve had from the book, can you see a time, can you foresee a time when default light becomes default darkness in the West? Do you think that’s a thing?

Leigh Ann: You know, I really do think that this is a conversation that is growing, and I hope that the book will help grow the conversation. And I truly do think that that it’s going to snowball in a sense, because we’re just becoming aware that this is an issue in a sense. And I’m hopeful, based on my personal experience and the response from the book, I do see that that there is a great deal of positive action and awareness and celebration of the dark. You know, if we can begin to celebrate the dark, I believe that we can reclaim the dark. Because it really is like reclaiming, you know, it’s rewilding, it’s reclaiming something. So many people have told me that they’ve just never thought about this before. And I was like, me too. There’s so many things in this book that I just had never thought about before. And once I started working on the book, I started noticing lights that I’d never noticed before. It just started making me map the world in different ways. And I really do have hope that as people gain that awareness and appreciation, that it really will translate to action, which I truly have seen in the response to the book.

Manda: Right. Brilliant. Excellent. Okay, we’re at the top of the hour. And everybody asks me what am I writing next? And actually, I find it really frustrating because there’s about six projects and I don’t know which one. Do you have a concept of another project or are you still kind of recovering from the the work of this one. Which would be perfectly reasonable if you are.

Leigh Ann: Well, I have been on the journey of seeing this one through, and I do have ideas and thoughts but it would take another hour probably to sort through them.

Manda: Okay. Well, we can come back for that. That would be great fun sometime. When you want to let me know we’ll schedule it in, because that would be grand. In the meantime, is there anything that you that we haven’t touched on that you would really like to, in closing? I have one factoid, which is that pirates who wore a patch, it wasn’t because they’d all been damaged in one eye; it was to keep one eye dark attuned for when they went below decks, which is so obvious once you hear it. And I had never understood that. So many things blew my mind, but I thought that was amazing. Have you got anything from your side that was mind blowing that you’d like to share?

Leigh Ann: You bring that one up and once you hear it, you’re like, this makes so much sense! And I actually don’t think it’s in the book, but historically, pilots actually used to wear red glasses for hours before they flew at night. Because not only is red light less disruptive for wildlife, actually it creates a slower siphoning of our own night vision. So it actually protects our night vision too. So they would wear these as to protect their night vision. Yeah. So the patch and the glasses kind of remind me of each other, yeah.

Manda: Okay. And when everyone’s read this book, I fully expect that we’ll see a lot less light around, which would be very, very nice. And more people sitting out overnight also, which would also be very good.

Leigh Ann: To say, you know, oh, she’s out sitting in the dark by herself again tonight. I mean, it’s so countercultural, but it’s such a gorgeous experience. I hope that people will be inspired. And I’m excited for people to read the book and talk about the book and whatever it brings up in terms of inspiring their own quests and journeys, no matter how close or far those might be. Because, again, you do not have to go very far to find something pretty magnificent and unexpected when you venture into the dark.

Manda: In your own area. So you can buy copies of the book, do what that lady did, hand them out, and then have dark appreciation meetings and discover what you’ve got. It’d be amazing. Yay!

Leigh Ann: That’s the dream.

Manda: All right. Fantastic. In that case. Leigh Ann, thank you so much for coming on to the Accidental Gods podcast. I look forward to whatever comes next and another conversation when it happens. Thank you.

Leigh Ann: Thank you so much for having me.

Manda: And there we go. That’s it for another week. Enormous thanks to Leigh Ann for all that she is and does and for her writing. Genuinely, I loved the craft of this book, the way it’s put together, the sense of deep intimacy and vulnerability and courage and the yearning to explore that took me out of myself and then brought me back in to the embodied sense of awe and wonder that arises innately whenever we come into genuine contact with the web of life, with the more than human world, with the majesty of everything that is outside the walls and the windows. So I know we’ve talked about a lot of books recently, it’s that time of year where a lot of people contacted me and said, hey, there’s this book, do you want to talk to the author? And I looked at them and I thought, yes, I really do. I looked at a lot more and thought, no, I really don’t. So I guarantee you about 1 in 10 of those that arrive actually get onto the podcast at the moment. But they are all the ones that are worth it. And this is so beautiful. It will make a fantastic gift for anyone in your life who really wants to engage with intelligent, thoughtful writing and with the world around them. Each of us has a life out there, beyond the walls and the windows that will absolutely spring to life as soon as we switch off the lights.

Manda: So head off, read it, explore it, create night parties in your own areas. That would be amazing. And then share it with your friends. So that’s our homework for this week. And that’s it for now. We will be back next week with another conversation. In the meantime, thanks to Caro C for the music at the Head and Foot. To Alan Lowell’s of Airtight Studios for, I hope, editing out the fact that there’s a puppy gnawing on something quite solid in the background. To Lou Mayor for the video, Anne Thomas for the transcripts, Faith Tilleray for managing all of the tech behind the scenes and for the long, long conversations in front of the fire that keep us moving forward. And as ever, an enormous thanks to you for listening. If you know of anybody else who would benefit from understanding that there is a world out there in the night, then please do send them this link. And if you have time to subscribe on whatever is the podcast app of your choice and give us five stars in a review, it genuinely makes a difference to the algorithms and we always appreciate that. Right. That’s us done. See you next week. Thank you and goodbye.

You may also like these recent podcasts

Water, Water Everywhere and none of it fit to drink! With Claire Kirby of Up Sewage Creek – ahead of World Water Day

Today, we’re talking about water, that utterly essential part of our biological and spiritual lives. It should be clean. It should be safe to drink, to swim in, for us and all the species with whom we share our beautiful blue pearl of a watery planet. As we all know… it’s not.

Kindling Quiet Romance: Reimagining the Law for Nature with Brontie Ansell of Lawyers for Nature

In the midst of collapse, it can be hard to imagine extending the franchise of legal rights and sovereignties to the More than Human world. And yet, if we’re to transcend this moment, it must be because we have become something other than we are now. To do this, we need the roadmaps that show us how to move through, and beyond, the collapse of the old into something new…

Healing our Fractured World: Re-Awakening Indigenous Consciousness with Marc-John Brown of the Native Wisdom Hub

As the old paradigm splinters into rage-filled, grief-stricken fragments, how can we lay the foundation for the total systemic change we so badly need?

Even beyond the listeners to this podcast, it is obvious by now that there is no going back. As Oliver Kornetzke wrote in a particularly sharply written piece on Facebook back on 22nd January – before Alex Pretti was murdered by Trump’s Federal Agents – what white America is not experiencing is not new, and is not a flaw in the system, it is the system…

Laws of Nature, Laws with Nature: Nature on Board with Alexandra Pimor of the Earth Law Center

Across the world, our legal systems are crumbling, the rule of sane law dismantled in real time. Yet at the same time, rivers, mountains, bees are being granted legal rights in ways that would have been thought impossible even a few years ago. And in boardrooms around the planet, C-suites and businesses are increasingly looking to the natural world for guidance on how to be in ways that heal the web of life. So how do we make this work? How do we ensure that it’s not just another layer of corporate greenwash?

STAY IN TOUCH

For a regular supply of ideas about humanity's next evolutionary step, insights into the thinking behind some of the podcasts, early updates on the guests we'll be having on the show - AND a free Water visualisation that will guide you through a deep immersion in water connection...sign up here.

(NB: This is a free newsletter - it's not joining up to the Membership! That's a nice, subtle pink button on the 'Join Us' page...)