Episode #66 Seeds of Change: Growing a different Future with Alan Watson Featherstone

Imagine a world where we find our life’s purpose – and have the courage to follow it. Alan Watson Featherstone listened to the prompting of his heart and set up Trees for Life to ReWild the Great Caledonian Forest in Scotland. Three decades on, there are thousands of acres alive with new growth. In this first of two podcasts, he describes his journey to Findhorn.

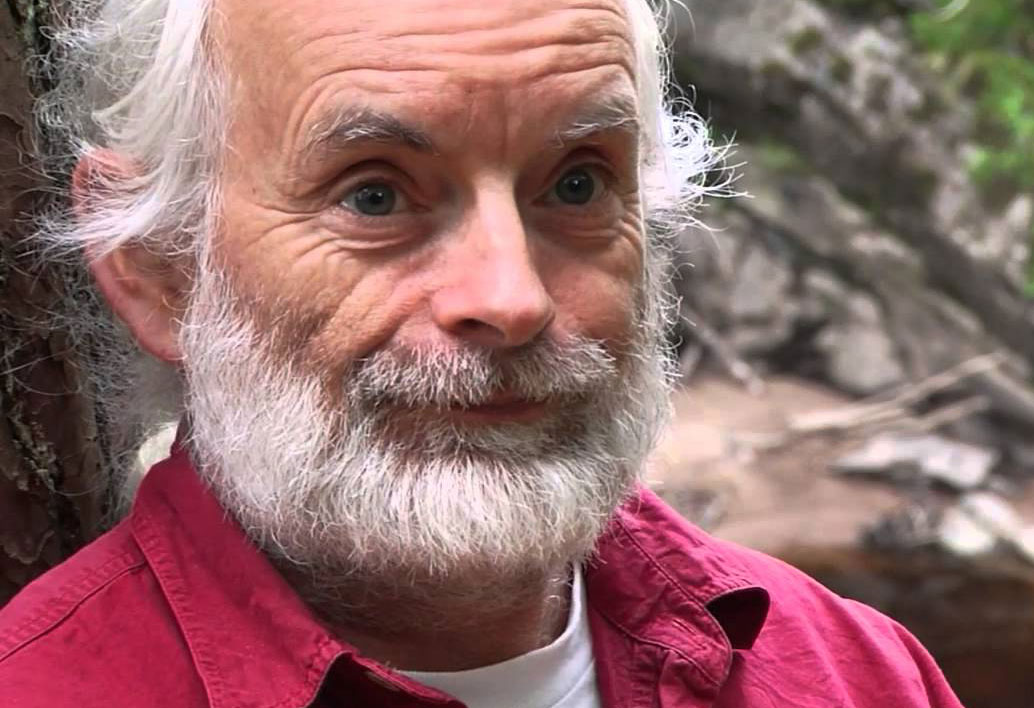

Alan is an ecologist, nature photographer, international speaker – and founder of Trees for Life, the charity that grew from a promise made at a Gathering, into a multi-million pound organisation owning – and ReWilding – thousands of acres of the Scottish Highlands. Along the way, he organised the planting of trees by the million, the fencing of thousands of acres to protect saplings – and helped lay the roots for the re-introduction of beavers to Scotland.

His journey from electronics undergraduate to one of the world’s foremost advocates for Wild Land and our connection with nature is an inspiration for anyone and everyone who seeks to connect with a sense of purpose in life.

Episode #66

LINKS

Alan’s website

Trees for Life

Findhorn community

Auroville community

Restore the Earth

Global Ecovillage Network

Dreaming Your Soul’s Path Gathering at Accidental Gods

Our header image this week was taken by Alan – Scots pines and birches in early autumn colour, with morning mist over Loch Beinn a’ Mheadhoin in Glen Affric

In Conversation

Manda: Hey, people, welcome to Accidental Gods, to the podcast where we believe that another world is still possible and that together, we can make this happen. I’m Manda Scott, your host at this place on the Web where art meets activism, politics meets philosophy and science meets spirituality, all in the service of Conscious Evolution. And this week’s podcast sits really squarely right in the centre of that. This is going to be the first of two parts: we didn’t plan it this way, but then we don’t usually plan exactly every podcast. It’s an emergent property of the moment. I spent a lot longer than I anticipated talking to Alan because his story, his clarity of thinking, the way that he expresses things feels so important and so timely and so right, to the extent that I didn’t do the usual five minutes of testing the sound and then head in: we were in right from the moment of first recording, and I realised that about five minutes in. So we don’t have the usual start. We just started talking, and I hope it’s immensely clear why we ended up doing that and why we have two podcasts. So people of the podcast, please welcome the first part of two parts with Alan Watson Featherstone.

Manda: Good morning, Alan. It’s lovely to see you. How are you?

Alan: Good to see you too, Manda. I’m very good. I’m on the ninth day of a fast at the moment, so I’m feeling really…

Manda: Oh, my goodness, Alan. Nine. How many days are you going to do in total?

Alan: Well, probably 14, up to this weekend.

Manda: 14 days of not eating.

Alan: Yeah, so I’m drinking, I drink herbal tea and a little bit of apple juice and a little bit of miso in the evening. But nothing else.

Manda: So you’ve got some electrolytes, because otherwise your body will begin to not really love it. I think the most I’ve ever done was five days, so I am in awe. And is there a reason behind this? You just fancy, do you?

Alan: Well, one of the reasons is spring clean for the body. I need to lose a little bit of weight. And the other thing is my wife is half Persian and half Japanese. And she grew up with a tradition of fasting leading up to the spring equinox, which is the Persian New Year, Nowruz. That’s part of the culture. So we’re both doing it at the moment.

Manda: Goodness. And so is it part of Persian culture to fast for 14 days leading up to the equinox?

Alan: I’m not sure exactly 14 days, but yes, in the lead up to it. But they they don’t do a complete fast. They do an Islamic type fast where they’re fasting during the hours of daylight. And they eat, you know, when it’s dark.

Manda: Gosh. But you’re not doing that thing. And do you do this every year?

Alan: We haven’t done it like this this year before, although my wife was fasting sometimes in the past at this time of year. But I’ve done a couple of fasts in the past two years, one for 12 days and one for 19 days.

Manda: Goodness. And so because this is not how I had planned to start, but we are where we are. And I always think of this podcast as being an emergent property of the moment and of the time. And I don’t eat before midday any day. So I basically I eat between 12 and eight. So I feel always very virtuous for the fact that I’m fasting from when I get up until afternoon. So the idea of going for 19 days, my goodness, 14 days even. How at what point do you stop getting headaches? This is a genuinely serious question because now I’m thinking maybe this is something I might want to do one day. Because I used to get really quite bad headaches around days three and four, and I’ve never gone beyond day five.

Alan: I have not had that as an issue. I think if I was just doing a pure water fast, that might be an issue, perhaps. But because I’m having a little bit of herbal tea, a little bit of warm apple juice and a cup of just pure miso in the evening, I think that avoids that sort of issue.

Manda: And so are you in the kind of light headed, very clean feeling by now, nine days in?

Alan: I’m not Light-Headed. I’m very clear. I feel I feel good in my body because I’ve been overweight. So it’s great to shed a few pounds and I feel quite connected with myself without having the drag of the body processing food. It’s like I’m more connected with my spirit somehow. I’m a bit purer.

Manda: Ok, and are you doing meditations that are linked to this that you wouldn’t otherwise do? Because I know that you meditate quite a lot anyway.

Alan: No, nothing specific. I spent the day out in nature yesterday. I do that usually one day a week, but that’s a lot of my meditation time, if you like, being out being still. Just being observant.

Manda: And the great thing about lockdown is that we are still able to go out if we live in a place where out is available. You live at Findhorn. I would have thought you’re pretty much in the natural world all of the time, are you not? Do you go somewhere specific now?

Alan: In the lockdown I’ve been going along the coast just east of here. There is a beautiful stretch of coastline starting about seven miles east of here and going for four miles. And it’s fantastic cliffs, there’s caves there, sea stacks. There’s wonderful eroded rock formations. And some of it is relatively easy to access, some much more challenging to access. So there’s not many people go there. And it’s this little strip of wilderness between the land and the sea. The Land here is all heavily farmed. And of course, this is lots of traffic because of the Murray Firth and fishing and everything. But the coastal strip is the wilderness. And it’s a wonderful, magical place.

Manda: Yes. And sea stacks! Do you do you climb, Alan?

Alan: I climbed one of the sea stacks yesterday, but it doesn’t require anything technical. But there were people climbing the cliffs there yesterday when I was there.

Manda: Anyway, we’re getting off track, getting on to the things that fascinate me. So I should have said at the start: welcome to Accidental Gods podcast. So now that we’re halfway in, welcome to the Accidental Gods podcast, Alan, and thank you for taking the time in the middle of your fast. I am genuinely very grateful. So this is an emergent property, we’ll get to where we get to, but I really wanted to talk to you about your life, and about how you came to be where you are now, and particularly about the route to Trees for Life, and then what’s happened since, where your life has taken you since, largely because I see this podcast as a way of helping people find agency in a world that is fast stripping away our agency, if we let it, and that it seemed to me that you are someone who who grasped agency with both hands and made it happen. So I know you’ve told the story before. It’s a TED talk. It’s various other things. But can you give us maybe the edited highlights of how Trees for Life came about and particularly your own process in the creation of that?

Alan: Certainly. Thanks, first of all, for the invitation to be part of your podcast series. We don’t have time to talk about it now, but I like the title Accidental Gods, I think is very fitting in many ways. So on my story, I suppose some goes back a long way. I’m Scottish. Originally I grew up in a sort of very normal conventional family, but I always felt like the odd one out. And my parents sent me to a boarding school when I was 11 and it was a very archaic 19th century institution stuck in the past. And I hated it. And it made me a rebel, it made me question everything. And I went to university after that to study electronics. I don’t know why I did. That was a crazy idea. I lost interest.

Manda: Part of being a rebel, obviously.

Alan: Yeah. But I really flowered at university after the very restricted situation of a boarding school away in the country, cut off from the world for most of the year, boys only.

Manda: Was it Gordonstoun? The one that Prince Charles was at?

Alan: No, called Strathallan, yeah. In Perthshire

Manda: Strathallan in Perthshire.

Alan: We used to play cricket and rugby with Gordonstoun, and there’s a whole circuit of boarding schools in Scotland. They’re all kind of operating in a similar fashion. I gave a presentation last year or two years ago at Gordonstoun about the work of Trees for Life. Gordonstoun, I think, has always been a bit more open and, you know, experimental. It’s still got elements from that past, but it is more, it’s got one foot at least in the twenty first century. But I haven’t spent any time there, so I can’t say for sure. But that’s my impression.

Manda: Right. We were about to… you went Uni and did electronics. And I’m guessing you were at Uni at a time when University was free. We hadn’t actually decided to turn the whole thing into a neoliberal slave trap yet. And I can imagine that disparity between the… the Scottish schools are designed, they’re put where they are because it’s as far from civilisation as you can get. So there’s basically no escape. You would die if you tried to run away. So you’ve gone from that level of restriction to a flourishing university at the time when university was there to be a life’s exploration. How did that feel?

Alan: Well, it was it was tremendously liberating. I actually went to Essex University in 1971, and at the time it was the most radical and liberal university in the country. And there were regular demonstrations and protests and student occupations, you know, it was a hotbed of left wing activism.

Manda: Yay. Your parents must’ve been thrilled!

I really flourished there. I got into a lot of student activities. I worked in the student wholefood shop, helped run the film society, did programmes on the student radio station and a lot of things like that. I put my foot into politics one year, but got very quickly disillusioned with student politics and got completely disillusioned with the academic world. And the course that I was on, it was very abstract, very impersonal, and it was very clear to me it was designed to train people to become a productive unit in society.

Manda: Right. And you didn’t really fancy being a productive unit in society.

Alan: Absolutely not, no. Because I also had what I consider to be my spiritual awakening when I was at university.

Manda: Oh, tell us more about that.

Alan: I think many people at the time and of course, still today, I experimented a bit with some, you know, mind altering drugs. I didn’t, I never smoked marijuana because I’ve never smoked a cigarette in my life. I always felt, why do I want to do that? My mother was a chain smoker. I hated smoke. So but and when I went to university, I was already doing a type of meditation that somebody at my boarding school had taught me without telling me what it was. You used the technique to relax and go to sleep. They never said it was meditation, but that’s what it was.

Manda: Well, this wasn’t one of the teachers. I’m guessing this was another pupil, was it?

Alan: No, it was a teacher. It was a German teacher who arrived just before I left. And that was interesting. You know, there’s always, like the yin yang, you know, in the middle of the dark, the black part of the yin yang there’s… you know? Even in the boarding school, you know, there’s a little bit of something different. So I was doing that. So most of my friends were smoking regularly and I didn’t do it. And then after a couple of years, I was out one day with some of them on a boating trip on a little waterway nearby at the weekend. And we were in a rowing boat and the sun was shining under the drops of water from the oars when they came out every time they were sparkling, and my two friends were high on acid at the time and they were describing the sparkles and what it meant, and what their experience was. And I thought, I can’t just dismiss this. You know, there’s something here they’re having something meaningful. So I experimented with LSD a little bit and it didn’t give me any answers, but it got me asking the right questions.

Manda: Oh, well done that, man. So you didn’t see sparkles in water that told you the meaning of life, the universe and everything?

Alan: No, but I could see visual things sometimes. But one day on one of these I had this experience of feeling this question come into my head, just like came down from the ceiling of the room, I was into my head and the question was, what is the purpose of life?

Manda: Right. Which, of course, is the key question for all of us.

Alan: Up till then, I dismissed that. I was I was coming from a rational scientific background. My course was electronics. And also I was coming from a scientific, logical field and there was no purpose to life. It was the result of a chance encounter of some pre-organic molecules billions of years ago. It was an accident. And then this moment when this question came into my head, I knew without a shadow of a doubt, there was a purpose to life. I didn’t know what it was. And that question burned in me for the next week or two, long beyond the effects of the psychedelic. And one day I had this insight, this revelation. And it was as a result of this exercise I’ve been doing about deep relaxation where I would lie in bed usually, sometimes sitting up. Usually I was in bed. I would consciously relax, starting with my toes, my feet, my ankles moving up, my legs of fingers, everything. And I would get into this different state. And my realisation was when I was doing that, that my consciousness was withdrawing from my body as I relax, and that I actually had this experience of who I was was embedded in my body, but it wasn’t my body. And I always felt like me was coming up somewhere around my chest or something like that.

Manda: So you’re having genuinely mystical primary realisations that lots of other people go to other spiritual teachers to be taught. But you were arriving at these first hand, so to speak.

Alan: Yep. So my insight was, I am not my body. I live in this body, but I am not my body. My identity is something other. And my revelation, personal revelation, rather grandiose, but it was tremendously exciting. It was like, wow. And my life is about discovering who I am. And allowing that self, the spiritual self, the inner self, to flourish and to flower, to come into full expression.

Alan: And did you share this with your friends at university? Were there a group of you who were coming into similar realisations at the same time, or was this unique to you, do you think?

Alan: I didn’t really have anybody I felt I could talk to about it at the time, and I stayed in that state for a day or two until I asked myself the next question, which was, OK, how do I go about this? How do I go about developing myself? I didn’t have an answer to that, although interestingly enough, I got a clue sometime later, quite independently. Again, through some friends, we did a sort of seance type thing using a homemade Ouija board where somebody had a round table. They put some, they cut up pieces of paper and put all the letters of the alphabet on it, turned upside down around the edge, and then put a sort of round tobacco tin on the centre upside down and everyone had to put their finger on it. And then they asked, you know, invited a spirit present. And we got two things. The first thing was a bit weird and it was a bit strange. I can’t remember what it said now. And we stopped and had a break. Then we came back at it again and we got something which was very profound. And it talked about this as you know, the thing would move around. And in the break, I was sceptical of this in the tea-break. I tried to move it by myself, like somebody’s manipulating this, but I couldn’t move it in the way it was moving when we all had our fingers on it . It was a genuine thing going on. And when we did this the second time, something very profound came through. It said, the first thing was something negative from the astral plane. But the second thing came out with this message. I can’t remember of the details of it all, but the thing that stayed with me ever since was: ‘You are the love you create.’

Manda: Woah. You spelled that out with a tobacco tin on the table? It was spelled out for you. Yes, yes, yes. Excellent.

Alan: You are the love you create.

Manda: How does that land with you?

Alan: That lands with me as a deep truth. I feel that is what we are here on Earth to learn, to manifest, to embody, and that is our gift to the world.

Manda: Brilliant. And did that land with you in that way, then, as well? You were in a space where you could hear that? Because I’m thinking, the way that we’re teaching with Accidental Gods, we’re endeavouring to get people in touch with their heart space. And a lot of people, quite reasonably and rightly, given the history of our culture, have real trouble doing that. But it sounds to me as if you were in a space by then where that could settle in and become the foundation of your life.

Alan: Not in any conscious way. I mean, it’s easy, but it’s easy for me, looking back now to link these things together. And at the time, these were just events in my life and this was in my final year at university. I had this huge black hole ahead of me. What am I going to do when I graduate?

Manda: Because possibly being an electronic engineer might not have been your thing by then?

Alan: Exactly. I’d long since lost interest in it. But it was like, what am I going to do? So the previous summer before my final year, I’d gone to Canada and worked in Toronto for four weeks and then hitchhiked across Canada all the way from Toronto to Vancouver Island, from Vancouver Island back to Newfoundland, and then back to Toronto in eight weeks.

Manda: And Canada’s amazing. But you came home. I think if I’d done that, I’m not sure I’d ever have bought a ticket home.

Alan: Yeah, the most important thing for me was in the Rocky Mountains in Canada. You know, I spent a few days there in Banff and Jasper national parks and the big mountains, the lakes, the untouched forests, the wildlife… elk came up to our car, the car was in, when I was hitchhiking, right outside the car window. And it was a revelation. It was like, wow. This is the world of nature, this is the way the world is supposed to be. So that was what I thought after my final year. What am I going to do? The idea that I’m going to travel, I’m going to experience the world. I need to open myself to the world and find something. And I also had this deep yearning to do something to make the world a better place. I’ve always felt there’s been an altruistic element. I look around, ever since I was a young teenager, and I think the world could be so much better than it is. And I remember, you know, I don’t know what age it was, drawing pictures of cities with no cars that were designed for people, and all sorts of things like that. So that always been inside me. It’s been a part of me. So my thing was, I’m going to travel. So I didn’t even stay at university to pick up my degree. I did get a token degree, didn’t mean much. I didn’t even stay to get that. Within a week of finishing exams and everything, I was gone. And I didn’t come back to Scotland for three and a half years.

So I went to Canada. I worked for a bit, but my mission was to go to South America. I had this impulse, I don’t know where it came from, this feeling to go to South America. So I travelled there when I was 21 overland from Mexico to Bolivia, seven months, and I learnt Spanish on the way. And this was the next stage of me coming out. The first stage of coming out had been going to university. Then this was coming further out into the world. And I didn’t find what I was looking for, which was what am I going to do with my life? I didn’t find a way to make a difference. I saw the destruction of the rainforest, the military governments oppressing their people. All the bad stuff that I’d protested and campaigned about as a student was there in my face. And I became a bit cynical at the time, because I felt like it’s too late for most people. We’ve got to educate people starting from their childhood years in a different way, because by the time people have gone through the educational system, which I’ve just had an experience of, they’ve been conditioned, brainwashed to become a unit of society. That’s what happens. And they go on and they get, you know, a career in a mortgage and they’re tied in and they’re stuck. And I was really wanting to avoid that, but I still didn’t find what I was looking for. So I made a trip to South America a year later. In between, I’d worked in Canada to raise some money. And at the end of that second trip back in Canada, and I decided to come home to Scotland to see my family, also because I was planning to emigrate to Canada. I had a girlfriend there by that time. I had a job which got me out into the wilderness for some of the time I was working. This is kind of a bit of a mixed bag in a way. I was working as a surveyor doing exploration work for mining companies, the very people tearing the earth apart. But I was one of the people on the surveys. We got to go out into the wilderness. We had encounters with grizzly bears and moose. And I spent a winter in the Yukon where it was minus 40 degrees, camped, an hour’s flight from the nearest road or house. And I had this tremendous wilderness experiences, but I was part of the machinery of the rape of the planet. Yeah, it gave me enough money from working for six months of the year to live and travel the rest of the year. So I was planning to do that. That was my future.

So I travelled across Canada, and I was in New York staying with a friend who had been a student with me at university before coming back home to Scotland. And two days before my flight home, after three and a half years away, in a little shop in Manhattan, in Greenwich Village, I was looking for something called the Mother Earth News magazine, a Back to the Land sort of permaculture type magazine, though permaculture didn’t exist yet, and I’d seen it in a vehicle I got a ride in when I’ve been hitchhiking. So I was in this little shop, and it was kind of one of these alternative shops, you know, a bit of herbalism, a bit of crafts and candles, alternative magazines and one rack of books. And I felt irresistibly drawn to this book rack. And there was this book that seemed to pull me: black, with a photograph on the cover, and it was called The Findhorn Gardens.

Manda: I remember that book!

Alan: And I had a quick flick through it. And the pictures really drew me in because I’d begun to discover a creative talent of nature photography myself by then. And the photographs seemed to really speak to me. Although they were in black and white, there was a radiance that shone through them. And I read these messages that accompanied some photographs from what they were termed as the day the spirit of the plants. And it was all about plants of consciousness, plants of intelligence, plants of purpose. And we can communicate with them. And we need to change our relationship from exploitation and domination to one of harmony, of cooperation and co-creation. Co-creation with nature, and that just rang all the bells, it was one of those moments where it’s like seeing something in black and white, it was, I know this inside myself, but I’ve never been able to articulate it or express it or make it conscious until that moment. And it was like a mirror. Now, sometimes, I think many people have that experience, seeing something externally like, this is truth inside me.

Manda: And feeling it on a bodily sense that is undeniable. Yes.

Alan: So when I came back to Scotland a few days later, I found out about Findhorn. They ran educational programmes. I came here in early 1978 and did the experience week. And I came expecting an experience of nature which I’ve read about in the book. But actually I arrived in the coldest winter Scotland had had in 30 years, and there was 30 centimetres of snow everywhere. The Findhorn garden, the famous garden of the book, was invisible.

Manda: Right under snow. Yes. Doesn’t the world organise things for us? So instead you experienced community, I guess?

Alan: Yeah, I experienced something much more important in a way, and a key step in my own development, and that was being in a group of like minded people. And I felt like from the first day where everybody was encouraged to introduce themselves: first thought was ‘get out of this’, a circle of twenty five strangers in there asking me to talk deeply and personally about myself. I was a very shy young man. You know, the thought of speaking in public in a group context terrified me. Fortunately, the circle, the people leading it, focalisers, we call them at Findhorn. They went round the circle, and I was situated not deliberately, just by chance, so-called, near the end. So I heard most of other people before came my turn and hearing was that, wow, these people are just like me. They’re asking deeper questions, they’re looking for meaning in their lives, they’re looking to make a positive difference in the world. And that gave me the courage to speak and share my truth. When I’d been working for this survey company, the people I worked with were all what they’re called the North America rednecks, they’d be Trump supporters. They’re out to make as much money as quickly as possible. Doesn’t matter what the damage to the planet is. You know, and I was the secret Greenpeace supporter in their midst who never dared admit that I’ve been leading this double life. I couldn’t share what was really important for me. So coming to Findhorn, I had the chance to do that, to be seen, to be acknowledged, to be heard.

And the whole thing about my week at Findhorn initially was encapsulated by a message I found in a bathroom, which is very interesting because I don’t know the history of Findhorn, but one of the founders, the founders, Peter and Eileen Caddy and their friend Dorothy McClean, and three children from the Caddys, lived in a caravan together for a number of years. That was where the community started. And Eileen Caddy couldn’t meditate there because of commotion, children or young boys running around. So she went to the toilet block in the caravan park to meditate. And that’s where she got all the guidance. So I don’t get guidance when I meditate. I don’t get clear messages most of the time. I get an intuition or a feeling sometimes. But I got guidance in a toilet at Findhorn, and the guidance was a little quotation that somebody had cut out of a magazine and pinned on the wall. And you know how in a magazine you’ve got an article and there’s blocks of text, and then they’ll highlight one in big letters. So this was one of those, and it was from the Russian writer, Alexander Solzhenitsyn. And I’d read some of his books in the past, but this was nothing to do with the Gulag or anything like that. It was a very simple quote that said, “If you want you to put the world to rights, where would you start: with yourself or with others?” End of quote. And that, in this week at Findhorn, hit the nail on the head for me because I realised I’ve been trying to change the world by changing others. It was those military governments I’d experienced in South America. It was greedy companies. It was corrupt politicians. They were the problem. They needed to change. And I’d exerted quite a lot of time on protests and demonstrations and trying to set up a recycling centre when I was in Vancouver in Canada and I had zero results to show for it. Nothing had changed and it was getting worse. It’s still getting worse in many cases in the world today.

Manda: There’s probably recycling in Vancouver by now.

Alan: Yes, but the overall trend is in the wrong direction still. The whole focus of Findhorn is that change has to come from within. And that was my revelation. I need to start putting the values of my heart into practise in my life. And what happened in my week at Findhorn was I got an experience of that because I always felt like my ideal life can only happen once all the problems of the world are solved, and we’ve got good governments, and all that stuff that’s preventing me. And when I was at Findhorn, living with like minded people, working consciously to give love to the plants in the garden, or to the dishes, or to the food that we prepared in the kitchens, all those things, it was like there’s nothing stopping me doing this right now, except my own sense of limitation. So that was my turning point in terms of really taking more responsibility for my life, not giving my power away. That was a key step in the journey of claiming my power and expressing my power. The power of my heart. The power of spirit lives in me, and spirit is in all of us. And many people, I think, never find the way to connect with it and to find their power and to express it. But I think that’s what we’re all here on Earth to learn, and to align that with the quality of love.

Manda: Yes. Yes. And somebody told me that they’ve been speaking to an astrologer recently who said, I’m going to misquote this Fiona, I’m sorry, but it was along the lines of… now is the time, and we’re a long time after you first went to Findhorn, but now in the next, this year, in the next year, is the time where love stops being an idea, and becomes consciousness. And if we can do that, that seems to me that is what we’re here for. So I really, for the people listening and for me, ‘that there was nothing stopping me except my own sense of limitation’ and that realising that was what was so empowering for you. So what did you do?

Alan: Well, I stayed at Findhorn for a second week. And just before I came to Findhorn, I’d applied to emigrate to Canada. And my application ran into all sorts of unexpected obstacles. I mean, I had a friend in Canada who was an immigration officer and he coached me. He told me what I needed to do. I needed to demonstrate I met all the criteria. A good education, could speak French, because Canada’s bilingual. I studied French at school, spoke a bit of French, had somebody who could sponsor me there, and an aunt in Canada, had a job offer. So I had a job offer from the company I’d been working for, and an aunt who could sponsor me. But it turned out my aunt had never taken out Canadian citizenship at the time. She’d been there for 20 years. So she couldn’t sponsor me. The job offer, they rejected that. They said there’s people out of work in this field. We’re not going to let you into that job. So the application just fell apart while I was at Findhorn. So in the second week when this was going on, I just felt this is feedback from the universe. I need to really… I’ve found what I’m looking for. And it wasn’t the place. It wasn’t Findhorn. But what I found was the courage to start living from the heart. I had an interview for joining Findhorn. I was accepted, but I said, I want to go back to Canada for the summer because I’ve got unfinished business there. I’ve got a girlfriend there. And I also wanted to see if I could incorporate these values and the changes I’ve been finding at Findhorn into life. I didn’t need to be at Findhorn to do that. But I also felt I need to be at Findhorn because this is where I can serve. This is where I can really contribute and make a difference.

So I went back to Canada and I made a lot of changes in my life. I quit the job. I had enough money to survive. I didn’t need to earn money. I had money saved up by then. I became vegetarian. And I’d been thinking about that, but hadn’t done it. But I’d seen in my travels in South America the rainforest getting cut down to create cattle pasture. And I don’t want to be part of that. I can claim my power and not be part of that by not eating meat. My circle of friends changed. I began to meditate more regularly, and I started volunteering for a spiritual organisation that was organising a big conference called The World Symposium on Humanity.

And every time I made one of these changes, it seemed like my life changed as well. When I found the book in New York City, I’d never heard of Findhorn, although I grew up in Scotland, never heard of the place, and gone halfway around the world and found out about it in New York. Most unlikely place, perhaps, but again, it’s like that little black circle in the middle of the white part of the yin yang. But after being here, when I got back to Canada, somehow Findhorn was everywhere. I began meeting people who had been to the community. I found magazine articles about the community. I walked into a bookshop one day and met somebody who had been involved with me in trying to set up the recycling centre the previous year. We were having a quick catch up and I said, Oh, I’ve been to Scotland and I’m planning to go back and live at Findhorn. He showed me the book he had under his arm. It was a Findhorn book, you know.

So it was like my life, because I started embodying the values of my heart, I changed. And because of that, my experience of the world changed too, and began to resonate and draw to myself like-minded people, situations, groups, organisations, and find myself in situations and things happening that supported me in my journey. So that took a period of six months. And then I came back to Findhorn in late 1978, joined the community and have been here ever since. And when I joined the community, I was asked in my membership interview, what did I think I could bring? What did I have to offer? And I don’t remember all the things I said. But the most important thing that stayed with me is deepening a connexion with nature and caring for the environment and doing something positive for the environment. Because when I’d come to Findhorn, you know, I’ve been inspired by the book, this talk of cooperation with nature. But when I arrived, most of the community was living in caravans which were radiating heat up into the atmosphere. And I’d been trying to set up a recycling centre in Vancouver. There was no recycling being done at Findhorn in those days. So although there was this work of cooperation with nature in the garden, that consciousness had not percolated through into other aspects of the community. So I felt I had something to offer there. So within a few months I started collecting paper for recycling and I began work in one of the kitchens. But I very quickly got drawn into the garden because in those days everybody had to share rooms. And my roommate was a gardener and he saw me with these sort of dead and dying house plants that I found and collected, and bring them back to life. And he said, we’ve got to get you into the garden. So I worked in the garden for four years and that was really important because that was where I learnt some of the fundamental principles that Findhorn was based upon. I had no experience of gardening and and the previous gardener had shifted jobs quite suddenly and wasn’t available to train me. So I had no person to show me what to do. I had to turn to the garden itself..

Manda: So you were the only person in the garden. I was expecting you to be part of a gang of about 16 people, but no.

Alan: There were other people in the garden. But I was in the vegetable garden and the others were doing other parts of the gardening, the flowers and different areas. And that was the way it turned out. So I had to basically turn to the garden itself, which was perfect, actually. It was challenging at the time, because I’m somebody coming from a logical, partially scientific background. I like to be prepared and trained and understand things. And I was thrown in the deep end, but it was actually just perfect because I had to cultivate powers of observation. And in the spring here in particular, you know, just as we’re coming into now, things grow very quickly in Scotland because we’ve got so much daylight after dark winter time. By the time we get to midsummer, we get 20 hours of daylight almost at Findhorn. So things grow quickly. So I was able to see plants growing and I was able to notice what they needed. And plants grow by themselves. Vegetables grow by themselves. But what I’ve begun to discover is that, yes, they need compost, they need water, they need light. But when they have an added ingredient, they grow better. And that new ingredient is human love. Because like everybody, I suppose I started growing things. I have some favourite vegetables I like to grow, the things I like to eat, you know, runner beans, courgettes and all those things.

And I could see them every day. I could see them growing. They’ll grow very quickly. I could notice the difference. And I built a relationship with them. So every day I go out to the garden, I go and look at them and say hello and how are you doing? And do you need… I’d pollinate the courgettes by hand, transferring pollen from the male flowers to the female flowers, an intimate connexion with them. So they flourished. But some of the other things in the garden that I was growing, they got the same physical situation. They got compost, they got water, but they didn’t get quite as much of my love. And the classic example for me was spring onions, which I still don’t like the flavour of spring onions. I tried growing those for three years in a row. I grew the seeds in nursery bed in the greenhouse, in nursery trays in the greenhouse, and pricked them out, planted them out. They got watered, they’d grow to be about two, three inches high and three years in a row they mysteriously fell over and died. And I never found a physical cause for it.

Manda: Interesting. So are they growing now, thriving now at Findhorn with different people gardening?

Alan: Other people grow them fine. Yes, it was my issue. It was, they were part of my teaching, my learning. You know, they weren’t getting my love.

Manda: And can I ask, so I remember reading that book about Findhorn. And by the time you got there, Eileen Caddy wasn’t there anymore. And the giant cabbage plant…

Alan: No, she was still in the community. Peter Caddy was still here, too, for the first year. And then they divorced and he left, but she lived until 2006. This was in 1978 when I came.

Manda: And she stayed at the community all that time.

Alan: Yes, she was here.

Manda: And then.. because the giant cabbages were such a key part…because like you I grew up in Scotland and never heard of Findhorn until I came as far away as England. It wasn’t quite as far as you. But the capacity to grow things on what looked like totally inhospitable, this kind of sand next to the caravan park seemed to be really deeply part of what Findhorn was about. So was that no longer the case, even by the time you got there in the late 70s?

Alan: Well, the gardens are still here, people are still working with the same relationship. Not all the gardeners have the same manifestation of connexion that Dorothy Maclean, the third founder did, she was the one who received the Deva messages. I’ve never received a Deva message, I don’t get that. But I do get communication from nature in other ways.

Manda: Yeah, it’s how you label it.

Alan: Flashes of insight. So there is the medium, the means, is not the important thing. It’s the connexion. Now there aren’t 40 pound cabbages grown here anymore. And when I was the gardener, I was wanting to grow 40 pound cabbages. I really did my best. And I realised after a little while not being successful, that was the wrong thing because in a sense, a 40 pound cabbage is just another expression of materialism. A bigger cabbage. That is not the point. That was the flag to draw attention. The point was co-creation with nature, developing a different relationship. And that is still what is happening here. There aren’t 40 pound cabbages anymore. That story is out there, it still brings lots of people. You’ve obviously heard about it. Many people come here because they hear about that. So that function doesn’t need to happen anymore, but it’s implementing it, co-creation with nature. Work is Love in Action is one of the three core principles of this community. So it’s working with love. And what I found was that plants respond to love.

Manda: And then growing stops becoming work, I’m guessing, and becomes part of your life, because…

Alan: Many people know that plants respond to love. How many of us know somebody who’s got a green thumb? Some elderly relative who dotes over their house plants or their roses, you know, and they shine. They have exactly the same thing. They may not express in that way. They may not even be conscious of it and able to articulate it. But that is the same thing. So and plants are like children or pets. Many people have that experience with pets, pets behave better when they’re loved. Children respond and become more whole and more alive when they’re surrounded by love. So one of my deep learnings at Findhorn is that all of life, all that is, and that includes so-called inanimate objects as well, responds to love. And love draws forth the inner potential and spirit within all that it is directed towards. So it strengthens, amplifies and nurtures the life force of everything.

Manda: Brilliant.

Alan: And that is a two way process, because if I give love to a plant or if I give love to my son, or to the cat that my wife and I have, they benefit from it, but I actually benefit too, because remember, you are the love you create. And when I express love, I become a fuller person. I become a bigger person. I become a more spiritually embodied person on the planet. And fulfilling my purpose.

Manda: Yes.

Alan: So, yeah, this is part of my training, Findhorn was described by Peter Caddy, one of the founders, as a Training Centre for World Servers. And that resonated deeply. And that is one of the major reasons why I came back to live here, because I’ve always, as I said earlier, had this feeling I need to do something positive to make a difference in the world. And the training here is not, it’s not a curriculum. It’s not a university course that’s laid out. It happens spontaneously. It happens perhaps without any clear and explicit guidance. Sometimes there is, but often it just happens spontaneously and of its own accord. So that was part of it. After four years in the garden, I moved into education and I ran the educational programmes here, the Experience Week as it’s called, for a year and a half, which was great. I felt like I could help provide the context, the vessel for people to have similar sorts of experiences to what I had when I was a guest. And that was meaningful and valuable. But it never felt like this is… my heart is not as fully engaged in this as it is with nature. I need to do something with nature. That’s what’s really calling me. So in 1985 I had a series of dreams. And sometimes I have dreams which speak to me really clearly. You know, most of the time they don’t. But this series of dreams is very profound. And it was about community in India called Auroville, which is closely linked with Findhorn. And I heard about it when I first arrived in 78, but I didn’t think much about it. It’s an interesting community, nothing to do with me. But I began having these dreams about Auroville and this was actually in 1984. I went in 1985. I had these dreams in 1984, and they ended up with me getting into a car and one of my dreams with somebody who lived at Findhorn had previously been in Auroville. And in the dream, in his car I fell asleep. And in the dream the car stopped and he woke me up and said, Alan, we’re here. It’s time to get out. I got out of the car and I was at Auroville. And at the same time I was finding information brochures about Auroville in one of the community lounges. So this is how Spirit speaks to me. You know, I don’t get guidance, a clear message, but things like this happen. I’ve learned to pay attention.

Manda: I think very few people get that sense of a download of plaintext. I think it’s really important for people listening that they understand that paying attention to the nudges that the universe gives us is a way to be able to come into your own power, and to have the courage to follow your heart, as you’re saying, and that when you do that, then the nudges, in my experience, then become more explicit. Is that your experience also?

Alan: Absolutely. It’s like paying attention to what what we call coincidences. Two or three people say the same thing in the space of a day. That’s a message I need to pay attention to that. I need to act on that. I know the spirit is speaking to me. And I think sometimes it’s because maybe on some level I’m not as sensitive as Eileen Caddy or Dorothy Mclean, who could meditate and get a clear message directly. You know, my body is tuned a bit differently. So the messages come from third parties, you know, and I think all of us get these communications and the challenge, the task is for us is to recognise them. And sometimes it’s different ways. Some people get it through their dreams. Some people get it through going to extreme sports, or when they’re singing in the shower to themselves every morning, they get a flash of insight. Or when they’re out jogging, you know, they get ideas. You know, so what is it that works for each individual? There’s no blueprint that’s the same for all of us. So for me, it’s learning to pay attention to these things and spirit speaks. Now, the other thing about going to Auroville was I had no money at the time. The money I saved in Canada had been used up to come to Findhorn and join the community. So I had a friend who was also interested in trees and going to Auroville. And we began talking about this and said, how can we go? And we didn’t have money. And one day I was sitting talking with her and I got a phone call. And at the time I lived in this big old hotel building that the community owns at Findhorn. And there was one telephone for like 40 people, you know, it was in the main reception area. So somebody came and said, Alan, there’s a phone call for you. So I went to answer it and pick up this phone. And the voice on the other end says, Oh, hi, is that Alan Watson Featherstone? Yes! My name is Nick Galley. I’m calling from Greenpeace to tell you that you’ve won first prize in our annual Christmas raffle. A thousand pounds in cash. I’d like to come and arrange a presentation so we can get some publicity. I did a lot of fundraising for Greenpeace in those days. I used to organise a local sponsored walk. I sold raffle tickets and various other things, which I’ve been supporting them a lot. So I had a few raffle tickets left over and paid for one or two myself. And I won this first prize. So I went back to this friend and I said, You’re not going to believe this, because I said to her, I trust that if it’s really right for me to go to Auroville, the money will appear. So, yes, that was why I went to Auroville. That was how I went there. And this was part of my ongoing education, because the training at Findhorn is not just learning about work is love in action, and that everything flourishes in an atmosphere of love. It’s also about what we call the laws of manifestation, and the laws of manifestation are that if I’m following my deepest calling in life, if I’m following my mission for why I’m here on Earth, the universe provides what I need to achieve that. Sometimes what it provides is unexpected. It’s not maybe what I always thought, but if I can look at it with that deeper perspective, there’s always a truth in that. And there’s something to be gained. There’s something to be learnt from it. So the experience of Auroville was very important for what became my life’s work. And I’ll talk about that later.

Manda: Thank you. Thank you. And I think this, the law of manifestation sounds to me so important, because in this area we end up with a lot of people who speak about a law of abundance, which is, as far as I can tell, if you want something hard enough, you can get it. But what I heard you say was, if I am following my deepest calling, if my heart is in alignment with the All That Is, with the heart-mind of the universe, then I will be supported in the action that the universe needs of me, which seems to me it’s not so far different, but it is significantly different from that. That’s fantastic. So thank you for what is about to become part one of a two part conversation. We will hold it there, and be back next week, people, with the other half which Alan and I are going to carry on recording around about now.

So that’s it for the first part of our conversation. Enormous thanks to Alan for the clarity of his expression, and for the inspiring story of his life. As you will have gathered, we hadn’t planned for this to be two parts. But if you are listening at the time of first transmission, which is to say 17th of March, and Alan’s ideas and thoughts and the story of his life have spoken to you and you think that you’re nearly there, or you’d like to be there, but you don’t quite know how, to interrogate your heart and find out if you are following whatever we call it, your heart’s true path, your true calling, something that makes your heart sing. Because this Saturday, the Equinox, March 20th, we’re running a gathering. I didn’t even know that’s what Findhorn calls its conferences, but that’s what we call our online workshops, whatever it is that we run through Accidental Gods. We’ve been planning this since the December solstice, but it seems very timely now because the aim is to help you to do that, to help you connect with your heart, to help you to know when you got that sense of resonance within that tells you that, yes, this this here now is on your life’s path. To help you identify when you are really in alignment with your calling. The plan is to spend six hours really looking into all aspects of intuition, because I think for most of us, it’s a muscle we need to exercise, and practise is the key.

But anyway, it is what it is. It’s online because Covid, and you can sign up on the events page of the website at AccidentalGods.life. It’s running from three o’clock in the afternoon till nine o’clock in the evening, U.K. time on Saturday. So hopefully as many of you in other time zones as possible can come along. So join us if you can. And all that aside, Alan and I will be back next week with the second part of this conversation. And in the meantime, as ever, thanks to Caro for awesome sound production, and for the signature music. Thanks to Faith for the website and the tech behind the scenes. And thanks to you for being there. For being our audience. For being the reason that we are here. If you want to support us, there is a Patreon page at AccidentalGods.life, and that’s where you’ll find the show notes with the links to everything that Alan is doing and to all of the other podcasts. You’ll also find the membership programme there if you want to delve more deeply into Conscious Evolution. And as ever, if you know of anybody else who would like to be part of the generative dance of the world, then please do send them this link.

And that’s it for now. See you next week. Thank you and goodbye.AG_pod_AlanWF_1_16mar21.mp3

Manda: Hey, people, welcome to Accidental Gods, to the podcast where we believe that another world is still possible and that together, we can make this happen. I’m Manda Scott, your host at this place on the Web where art meets activism, politics meets philosophy and science meets spirituality, all in the service of Conscious Evolution. And this week’s podcast sits really squarely right in the centre of that. This is going to be the first of two parts: we didn’t plan it this way, but then we don’t usually plan exactly every podcast. It’s an emergent property of the moment. I spent a lot longer than I anticipated talking to Alan because his story, his clarity of thinking, the way that he expresses things feels so important and so timely and so right, to the extent that I didn’t do the usual five minutes of testing the sound and then head in: we were in right from the moment of first recording, and I realised that about five minutes in. So we don’t have the usual start. We just started talking, and I hope it’s immensely clear why we ended up doing that and why we have two podcasts. So people of the podcast, please welcome the first part of two parts with Alan Watson Featherstone.

Manda: Good morning, Alan. It’s lovely to see you. How are you?

Alan: Good to see you too, Manda. I’m very good. I’m on the ninth day of a fast at the moment, so I’m feeling really…

Manda: Oh, my goodness, Alan. Nine. How many days are you going to do in total?

Alan: Well, probably 14, up to this weekend.

Manda: 14 days of not eating.

Alan: Yeah, so I’m drinking, I drink herbal tea and a little bit of apple juice and a little bit of miso in the evening. But nothing else.

Manda: So you’ve got some electrolytes, because otherwise your body will begin to not really love it. I think the most I’ve ever done was five days, so I am in awe. And is there a reason behind this? You just fancy, do you?

Alan: Well, one of the reasons is spring clean for the body. I need to lose a little bit of weight. And the other thing is my wife is half Persian and half Japanese. And she grew up with a tradition of fasting leading up to the spring equinox, which is the Persian New Year, Nowruz. That’s part of the culture. So we’re both doing it at the moment.

Manda: Goodness. And so is it part of Persian culture to fast for 14 days leading up to the equinox?

Alan: I’m not sure exactly 14 days, but yes, in the lead up to it. But they they don’t do a complete fast. They do an Islamic type fast where they’re fasting during the hours of daylight. And they eat, you know, when it’s dark.

Manda: Gosh. But you’re not doing that thing. And do you do this every year?

Alan: We haven’t done it like this this year before, although my wife was fasting sometimes in the past at this time of year. But I’ve done a couple of fasts in the past two years, one for 12 days and one for 19 days.

Manda: Goodness. And so because this is not how I had planned to start, but we are where we are. And I always think of this podcast as being an emergent property of the moment and of the time. And I don’t eat before midday any day. So I basically I eat between 12 and eight. So I feel always very virtuous for the fact that I’m fasting from when I get up until afternoon. So the idea of going for 19 days, my goodness, 14 days even. How at what point do you stop getting headaches? This is a genuinely serious question because now I’m thinking maybe this is something I might want to do one day. Because I used to get really quite bad headaches around days three and four, and I’ve never gone beyond day five.

Alan: I have not had that as an issue. I think if I was just doing a pure water fast, that might be an issue, perhaps. But because I’m having a little bit of herbal tea, a little bit of warm apple juice and a cup of just pure miso in the evening, I think that avoids that sort of issue.

Manda: And so are you in the kind of light headed, very clean feeling by now, nine days in?

Alan: I’m not Light-Headed. I’m very clear. I feel I feel good in my body because I’ve been overweight. So it’s great to shed a few pounds and I feel quite connected with myself without having the drag of the body processing food. It’s like I’m more connected with my spirit somehow. I’m a bit purer.

Manda: Ok, and are you doing meditations that are linked to this that you wouldn’t otherwise do? Because I know that you meditate quite a lot anyway.

Alan: No, nothing specific. I spent the day out in nature yesterday. I do that usually one day a week, but that’s a lot of my meditation time, if you like, being out being still. Just being observant.

Manda: And the great thing about lockdown is that we are still able to go out if we live in a place where out is available. You live at Findhorn. I would have thought you’re pretty much in the natural world all of the time, are you not? Do you go somewhere specific now?

Alan: In the lockdown I’ve been going along the coast just east of here. There is a beautiful stretch of coastline starting about seven miles east of here and going for four miles. And it’s fantastic cliffs, there’s caves there, sea stacks. There’s wonderful eroded rock formations. And some of it is relatively easy to access, some much more challenging to access. So there’s not many people go there. And it’s this little strip of wilderness between the land and the sea. The Land here is all heavily farmed. And of course, this is lots of traffic because of the Murray Firth and fishing and everything. But the coastal strip is the wilderness. And it’s a wonderful, magical place.

Manda: Yes. And sea stacks! Do you do you climb, Alan?

Alan: I climbed one of the sea stacks yesterday, but it doesn’t require anything technical. But there were people climbing the cliffs there yesterday when I was there.

Manda: Anyway, we’re getting off track, getting on to the things that fascinate me. So I should have said at the start: welcome to Accidental Gods podcast. So now that we’re halfway in, welcome to the Accidental Gods podcast, Alan, and thank you for taking the time in the middle of your fast. I am genuinely very grateful. So this is an emergent property, we’ll get to where we get to, but I really wanted to talk to you about your life, and about how you came to be where you are now, and particularly about the route to Trees for Life, and then what’s happened since, where your life has taken you since, largely because I see this podcast as a way of helping people find agency in a world that is fast stripping away our agency, if we let it, and that it seemed to me that you are someone who who grasped agency with both hands and made it happen. So I know you’ve told the story before. It’s a TED talk. It’s various other things. But can you give us maybe the edited highlights of how Trees for Life came about and particularly your own process in the creation of that?

Alan: Certainly. Thanks, first of all, for the invitation to be part of your podcast series. We don’t have time to talk about it now, but I like the title Accidental Gods, I think is very fitting in many ways. So on my story, I suppose some goes back a long way. I’m Scottish. Originally I grew up in a sort of very normal conventional family, but I always felt like the odd one out. And my parents sent me to a boarding school when I was 11 and it was a very archaic 19th century institution stuck in the past. And I hated it. And it made me a rebel, it made me question everything. And I went to university after that to study electronics. I don’t know why I did. That was a crazy idea. I lost interest.

Manda: Part of being a rebel, obviously.

Alan: Yeah. But I really flowered at university after the very restricted situation of a boarding school away in the country, cut off from the world for most of the year, boys only.

Manda: Was it Gordonstoun? The one that Prince Charles was at?

Alan: No, called Strathallan, yeah. In Perthshire

Manda: Strathallan in Perthshire.

Alan: We used to play cricket and rugby with Gordonstoun, and there’s a whole circuit of boarding schools in Scotland. They’re all kind of operating in a similar fashion. I gave a presentation last year or two years ago at Gordonstoun about the work of Trees for Life. Gordonstoun, I think, has always been a bit more open and, you know, experimental. It’s still got elements from that past, but it is more, it’s got one foot at least in the twenty first century. But I haven’t spent any time there, so I can’t say for sure. But that’s my impression.

Manda: Right. We were about to… you went Uni and did electronics. And I’m guessing you were at Uni at a time when University was free. We hadn’t actually decided to turn the whole thing into a neoliberal slave trap yet. And I can imagine that disparity between the… the Scottish schools are designed, they’re put where they are because it’s as far from civilisation as you can get. So there’s basically no escape. You would die if you tried to run away. So you’ve gone from that level of restriction to a flourishing university at the time when university was there to be a life’s exploration. How did that feel?

Alan: Well, it was it was tremendously liberating. I actually went to Essex University in 1971, and at the time it was the most radical and liberal university in the country. And there were regular demonstrations and protests and student occupations, you know, it was a hotbed of left wing activism.

Manda: Yay. Your parents must’ve been thrilled!

I really flourished there. I got into a lot of student activities. I worked in the student wholefood shop, helped run the film society, did programmes on the student radio station and a lot of things like that. I put my foot into politics one year, but got very quickly disillusioned with student politics and got completely disillusioned with the academic world. And the course that I was on, it was very abstract, very impersonal, and it was very clear to me it was designed to train people to become a productive unit in society.

Manda: Right. And you didn’t really fancy being a productive unit in society.

Alan: Absolutely not, no. Because I also had what I consider to be my spiritual awakening when I was at university.

Manda: Oh, tell us more about that.

Alan: I think many people at the time and of course, still today, I experimented a bit with some, you know, mind altering drugs. I didn’t, I never smoked marijuana because I’ve never smoked a cigarette in my life. I always felt, why do I want to do that? My mother was a chain smoker. I hated smoke. So but and when I went to university, I was already doing a type of meditation that somebody at my boarding school had taught me without telling me what it was. You used the technique to relax and go to sleep. They never said it was meditation, but that’s what it was.

Manda: Well, this wasn’t one of the teachers. I’m guessing this was another pupil, was it?

Alan: No, it was a teacher. It was a German teacher who arrived just before I left. And that was interesting. You know, there’s always, like the yin yang, you know, in the middle of the dark, the black part of the yin yang there’s… you know? Even in the boarding school, you know, there’s a little bit of something different. So I was doing that. So most of my friends were smoking regularly and I didn’t do it. And then after a couple of years, I was out one day with some of them on a boating trip on a little waterway nearby at the weekend. And we were in a rowing boat and the sun was shining under the drops of water from the oars when they came out every time they were sparkling, and my two friends were high on acid at the time and they were describing the sparkles and what it meant, and what their experience was. And I thought, I can’t just dismiss this. You know, there’s something here they’re having something meaningful. So I experimented with LSD a little bit and it didn’t give me any answers, but it got me asking the right questions.

Manda: Oh, well done that, man. So you didn’t see sparkles in water that told you the meaning of life, the universe and everything?

Alan: No, but I could see visual things sometimes. But one day on one of these I had this experience of feeling this question come into my head, just like came down from the ceiling of the room, I was into my head and the question was, what is the purpose of life?

Manda: Right. Which, of course, is the key question for all of us.

Alan: Up till then, I dismissed that. I was I was coming from a rational scientific background. My course was electronics. And also I was coming from a scientific, logical field and there was no purpose to life. It was the result of a chance encounter of some pre-organic molecules billions of years ago. It was an accident. And then this moment when this question came into my head, I knew without a shadow of a doubt, there was a purpose to life. I didn’t know what it was. And that question burned in me for the next week or two, long beyond the effects of the psychedelic. And one day I had this insight, this revelation. And it was as a result of this exercise I’ve been doing about deep relaxation where I would lie in bed usually, sometimes sitting up. Usually I was in bed. I would consciously relax, starting with my toes, my feet, my ankles moving up, my legs of fingers, everything. And I would get into this different state. And my realisation was when I was doing that, that my consciousness was withdrawing from my body as I relax, and that I actually had this experience of who I was was embedded in my body, but it wasn’t my body. And I always felt like me was coming up somewhere around my chest or something like that.

Manda: So you’re having genuinely mystical primary realisations that lots of other people go to other spiritual teachers to be taught. But you were arriving at these first hand, so to speak.

Alan: Yep. So my insight was, I am not my body. I live in this body, but I am not my body. My identity is something other. And my revelation, personal revelation, rather grandiose, but it was tremendously exciting. It was like, wow. And my life is about discovering who I am. And allowing that self, the spiritual self, the inner self, to flourish and to flower, to come into full expression.

Alan: And did you share this with your friends at university? Were there a group of you who were coming into similar realisations at the same time, or was this unique to you, do you think?

Alan: I didn’t really have anybody I felt I could talk to about it at the time, and I stayed in that state for a day or two until I asked myself the next question, which was, OK, how do I go about this? How do I go about developing myself? I didn’t have an answer to that, although interestingly enough, I got a clue sometime later, quite independently. Again, through some friends, we did a sort of seance type thing using a homemade Ouija board where somebody had a round table. They put some, they cut up pieces of paper and put all the letters of the alphabet on it, turned upside down around the edge, and then put a sort of round tobacco tin on the centre upside down and everyone had to put their finger on it. And then they asked, you know, invited a spirit present. And we got two things. The first thing was a bit weird and it was a bit strange. I can’t remember what it said now. And we stopped and had a break. Then we came back at it again and we got something which was very profound. And it talked about this as you know, the thing would move around. And in the break, I was sceptical of this in the tea-break. I tried to move it by myself, like somebody’s manipulating this, but I couldn’t move it in the way it was moving when we all had our fingers on it . It was a genuine thing going on. And when we did this the second time, something very profound came through. It said, the first thing was something negative from the astral plane. But the second thing came out with this message. I can’t remember of the details of it all, but the thing that stayed with me ever since was: ‘You are the love you create.’

Manda: Woah. You spelled that out with a tobacco tin on the table? It was spelled out for you. Yes, yes, yes. Excellent.

Alan: You are the love you create.

Manda: How does that land with you?

Alan: That lands with me as a deep truth. I feel that is what we are here on Earth to learn, to manifest, to embody, and that is our gift to the world.

Manda: Brilliant. And did that land with you in that way, then, as well? You were in a space where you could hear that? Because I’m thinking, the way that we’re teaching with Accidental Gods, we’re endeavouring to get people in touch with their heart space. And a lot of people, quite reasonably and rightly, given the history of our culture, have real trouble doing that. But it sounds to me as if you were in a space by then where that could settle in and become the foundation of your life.

Alan: Not in any conscious way. I mean, it’s easy, but it’s easy for me, looking back now to link these things together. And at the time, these were just events in my life and this was in my final year at university. I had this huge black hole ahead of me. What am I going to do when I graduate?

Manda: Because possibly being an electronic engineer might not have been your thing by then?

Alan: Exactly. I’d long since lost interest in it. But it was like, what am I going to do? So the previous summer before my final year, I’d gone to Canada and worked in Toronto for four weeks and then hitchhiked across Canada all the way from Toronto to Vancouver Island, from Vancouver Island back to Newfoundland, and then back to Toronto in eight weeks.

Manda: And Canada’s amazing. But you came home. I think if I’d done that, I’m not sure I’d ever have bought a ticket home.

Alan: Yeah, the most important thing for me was in the Rocky Mountains in Canada. You know, I spent a few days there in Banff and Jasper national parks and the big mountains, the lakes, the untouched forests, the wildlife… elk came up to our car, the car was in, when I was hitchhiking, right outside the car window. And it was a revelation. It was like, wow. This is the world of nature, this is the way the world is supposed to be. So that was what I thought after my final year. What am I going to do? The idea that I’m going to travel, I’m going to experience the world. I need to open myself to the world and find something. And I also had this deep yearning to do something to make the world a better place. I’ve always felt there’s been an altruistic element. I look around, ever since I was a young teenager, and I think the world could be so much better than it is. And I remember, you know, I don’t know what age it was, drawing pictures of cities with no cars that were designed for people, and all sorts of things like that. So that always been inside me. It’s been a part of me. So my thing was, I’m going to travel. So I didn’t even stay at university to pick up my degree. I did get a token degree, didn’t mean much. I didn’t even stay to get that. Within a week of finishing exams and everything, I was gone. And I didn’t come back to Scotland for three and a half years.

So I went to Canada. I worked for a bit, but my mission was to go to South America. I had this impulse, I don’t know where it came from, this feeling to go to South America. So I travelled there when I was 21 overland from Mexico to Bolivia, seven months, and I learnt Spanish on the way. And this was the next stage of me coming out. The first stage of coming out had been going to university. Then this was coming further out into the world. And I didn’t find what I was looking for, which was what am I going to do with my life? I didn’t find a way to make a difference. I saw the destruction of the rainforest, the military governments oppressing their people. All the bad stuff that I’d protested and campaigned about as a student was there in my face. And I became a bit cynical at the time, because I felt like it’s too late for most people. We’ve got to educate people starting from their childhood years in a different way, because by the time people have gone through the educational system, which I’ve just had an experience of, they’ve been conditioned, brainwashed to become a unit of society. That’s what happens. And they go on and they get, you know, a career in a mortgage and they’re tied in and they’re stuck. And I was really wanting to avoid that, but I still didn’t find what I was looking for. So I made a trip to South America a year later. In between, I’d worked in Canada to raise some money. And at the end of that second trip back in Canada, and I decided to come home to Scotland to see my family, also because I was planning to emigrate to Canada. I had a girlfriend there by that time. I had a job which got me out into the wilderness for some of the time I was working. This is kind of a bit of a mixed bag in a way. I was working as a surveyor doing exploration work for mining companies, the very people tearing the earth apart. But I was one of the people on the surveys. We got to go out into the wilderness. We had encounters with grizzly bears and moose. And I spent a winter in the Yukon where it was minus 40 degrees, camped, an hour’s flight from the nearest road or house. And I had this tremendous wilderness experiences, but I was part of the machinery of the rape of the planet. Yeah, it gave me enough money from working for six months of the year to live and travel the rest of the year. So I was planning to do that. That was my future.

So I travelled across Canada, and I was in New York staying with a friend who had been a student with me at university before coming back home to Scotland. And two days before my flight home, after three and a half years away, in a little shop in Manhattan, in Greenwich Village, I was looking for something called the Mother Earth News magazine, a Back to the Land sort of permaculture type magazine, though permaculture didn’t exist yet, and I’d seen it in a vehicle I got a ride in when I’ve been hitchhiking. So I was in this little shop, and it was kind of one of these alternative shops, you know, a bit of herbalism, a bit of crafts and candles, alternative magazines and one rack of books. And I felt irresistibly drawn to this book rack. And there was this book that seemed to pull me: black, with a photograph on the cover, and it was called The Findhorn Gardens.

Manda: I remember that book!

Alan: And I had a quick flick through it. And the pictures really drew me in because I’d begun to discover a creative talent of nature photography myself by then. And the photographs seemed to really speak to me. Although they were in black and white, there was a radiance that shone through them. And I read these messages that accompanied some photographs from what they were termed as the day the spirit of the plants. And it was all about plants of consciousness, plants of intelligence, plants of purpose. And we can communicate with them. And we need to change our relationship from exploitation and domination to one of harmony, of cooperation and co-creation. Co-creation with nature, and that just rang all the bells, it was one of those moments where it’s like seeing something in black and white, it was, I know this inside myself, but I’ve never been able to articulate it or express it or make it conscious until that moment. And it was like a mirror. Now, sometimes, I think many people have that experience, seeing something externally like, this is truth inside me.

Manda: And feeling it on a bodily sense that is undeniable. Yes.

Alan: So when I came back to Scotland a few days later, I found out about Findhorn. They ran educational programmes. I came here in early 1978 and did the experience week. And I came expecting an experience of nature which I’ve read about in the book. But actually I arrived in the coldest winter Scotland had had in 30 years, and there was 30 centimetres of snow everywhere. The Findhorn garden, the famous garden of the book, was invisible.

Manda: Right under snow. Yes. Doesn’t the world organise things for us? So instead you experienced community, I guess?

Alan: Yeah, I experienced something much more important in a way, and a key step in my own development, and that was being in a group of like minded people. And I felt like from the first day where everybody was encouraged to introduce themselves: first thought was ‘get out of this’, a circle of twenty five strangers in there asking me to talk deeply and personally about myself. I was a very shy young man. You know, the thought of speaking in public in a group context terrified me. Fortunately, the circle, the people leading it, focalisers, we call them at Findhorn. They went round the circle, and I was situated not deliberately, just by chance, so-called, near the end. So I heard most of other people before came my turn and hearing was that, wow, these people are just like me. They’re asking deeper questions, they’re looking for meaning in their lives, they’re looking to make a positive difference in the world. And that gave me the courage to speak and share my truth. When I’d been working for this survey company, the people I worked with were all what they’re called the North America rednecks, they’d be Trump supporters. They’re out to make as much money as quickly as possible. Doesn’t matter what the damage to the planet is. You know, and I was the secret Greenpeace supporter in their midst who never dared admit that I’ve been leading this double life. I couldn’t share what was really important for me. So coming to Findhorn, I had the chance to do that, to be seen, to be acknowledged, to be heard.